Plan D: Deluded. Dishonest. ‘Dire Wolves’

The following offers a detailed exploration of the dishonesty presented by Colossal Bioscience in their proclamation of the de-extinct ‘dire wolf’. It recognises capitalism’s latest attempt to sell a solution that abdicates responsibility for ecocide through superficial creations, and positions this with the larger crisis of ecocide.

April 2025: Headlines proclaiming the return of the Dire Wolf abound. Extinct as of 8,200-12,700 years ago (O’Keefe et al., 2014; Hester, 1960), interest in the species spiked following the popularity of the HBO series Game of Thrones (Parkel, 2025) – to the extent that the third-born ‘dire wolf’ pup bears the name Khaleesi (an in-universe regal title). The other two hold the names Romulus and Remus from Roman mythology. Fantasies of Jurassic Park-esque labs are rife in public discourse, encompassing both the excitement and absurdity of the initiative. But, what do these three pups – bred in just eighteen months – indicate about the coming fight against ecocide?

Texas-based US genetic engineering firm Colossal Biosciences has dominated headlines since their founding in 2021 with proclaimed remits of reviving woolly mammoths, Tasmanian tigers, and dodos. There is speculation, however, over their work’s potential for reviving the Yangtze River dolphin and other more recent losses. Earlier this year, McCarthy (2025) hypothesised that ‘[a]s humans living in a society disconnected from nature, we are all searching for a more meaningful relationship with the world around us’. If this holds true, in premise, the chance to build a world that reintroduces Pleistocene megafauna as majestic as the woolly mammoth, Irish elk, woolly rhinoceros, ground sloth, Diprotodon, Giant Short-faced Kangaroo, or even the cave lion is an opportunity few could resist. Yet, the reality is none of us involved in community-based ecological sustainability will ever hold power in this context, nor is it necessarily something we should delude ourselves is a sure-fire positive direction.

Dishonest…

When ‘sustainability’ is often rendered a mere buzzword for corporations and states, it’s essential that efforts to construct alternative ways of being take far more concrete forms than mere reformism for, abstract as the de-extinction of species such as the woolly mammoth remains, the notion that recently extinct species can readily be recovered fosters a false sense of security. With this seeming breakthrough, Castree’s (2008) observed ‘neo liberalising nature’ – a process which McCormack (2023) states ‘gave birth to […] market solutions of various sorts to the threat of the future habitability of the planet’ – leaves no urgency in addressing the Anthropocene.

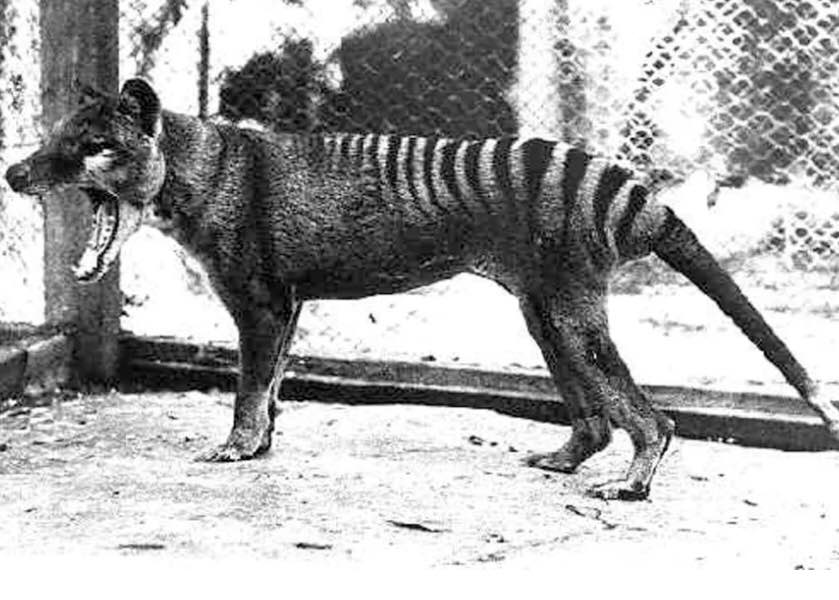

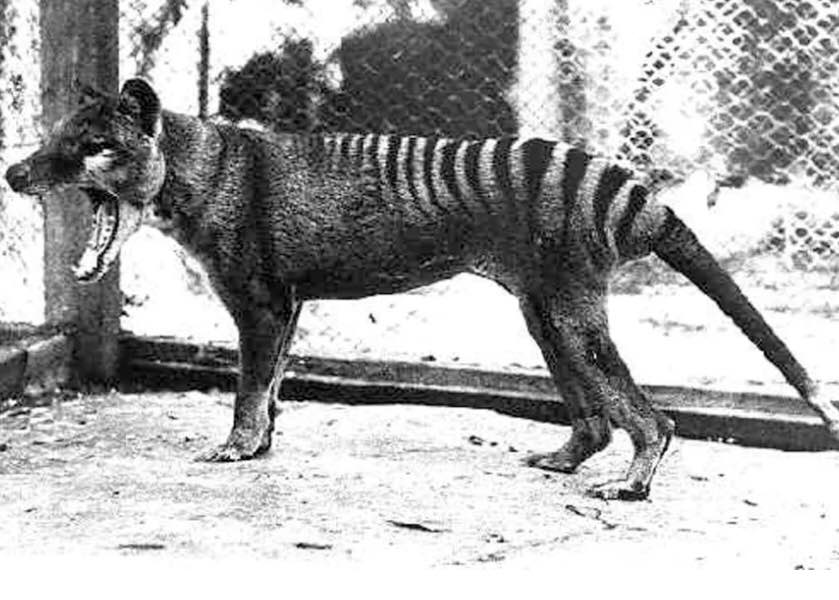

Partnering with the University of Melbourne (Australia) as they attempt to ‘de-extinct’ the Tasmanian Tiger – the last known captivate ‘died due to gross neglect’ at Beaumaris Zoo in 1936 (Everitt, 2022) – affords Colossal Biosciences a legitimacy that allows those in power to abdicate responsibility for sustaining habitats and relieves them of their duties of preservation. Capitalism – sorry, ‘computational advances’, as described by Beth Shapiro (2025; Colossal Biosciences’ chief science officer) – has presented them an outcome whereby, with enough investment, they can fund a replacement that somewhat resembles the original species.

It has long been the case that aesthetically cute species (such as the Panda) have received significantly disproportionate levels of academic interest and funding (both from the public and donor bodies). So much so, that Trimble and van Aarde (2010, p.890) found in their study of ‘the scientific equity [centred on] relating the number of papers written about each species to their status on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List’, that ‘popular species to study are more charismatic than other species (bigger, cuter, and more interesting)’. The aesthetic or ‘cuteness factor’ prompted Adam and Cole (2010) to ask of the endangered African Manatee, ‘should an unprepossessing mugshot condemn a species to extinction?’. Similar concerns have been raised over the Cuban Greater Funnel-eared Bat or the giant golden mole (Veríssimo and Smith, 2017), yet, the very notion that de-extinction is possible fosters an illusion that if things have to get a little worse before action is taken so be it… Seymour (2024) claimed as humanity ‘[w]e are passionate animals’, yet, it’s perhaps fairer to say we are compassionate for our fellow animals if they possess the traits that matter to us.

McCormack (2023) echoes this, believing the hope ‘that rational science could trump denialism is again on the backfoot with a growth in outright climate denial and a marriage between resurgent far-right movements and climate scepticism and denial’. Fundamentally, capitalism cannot co-exist with sustainable society, indeed, ‘only the overthrow of capital can ultimately stop the threatened mass extinction of life’. Certainly, humanity bears direct responsibility for the extinction of many species – overconsumption, encroaching habitats, etc. (Goebel et al, 2008; Martin, 1984; Barnosky et al., 2004); it seems few lessons have been learnt, with this the continued consequence of accepting ‘cheap meat and dairy but [leaving] the land stripped bare and rivers choked by excess nitrogen’ (Spear, 2025).

Arguably worse, however, is the inaction taken to safeguard those species we know to be near extinction, neglecting the final survivors or continuing to endanger their habitats – a cocktail of ‘ocean acidification and atmospheric carbon with profitable opportunity’ regardless of the cost (Chaudhary, 2024, p.61). Coleman (2021) even queries the flaws with ‘the idea that “humanity” is guilty, rather than a specific fraction of humanity or a system we live under [that can] lead us to pathologise the cause of climate change as an inherent part of human civilisation’. What we need, then, according to Spear (2025), is ‘a politics that soberly acknowledges the world we’re inheriting – climate chaos, gargantuan levels of pollution, extinction, and sea level rise to start’; not a world where we dishonestly tell ourselves we can replace a dead species as we deem it necessary.

‘Dire Wolves’…

The tv adaptation of George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series pushed the dire wolf into popular culture, having previously been relegated to high fantasy novels, board games, etc.. Martin’s status as a celebrity pouring significant investment into Colossal Biosciences may rationalise prioritisation of the extinct canine over other species, affording the corporation a global platform from which to push for further investment; the author also holds a cultural adviser title at the company – hence the nonsensical statement claiming ‘Colossal have created magic by bringing these majestic beasts back to our world’ (Martin, 2025). Consequently, despite more recent issues with extinction as a direct consequence of human (in)action (e.g. Schomburgk’s Deer, Steller’s sea cow, and the Great Auk), popularity is already a key marker for which species will receive investment.

Vincent Lynch (2025; University of Buffalo [New York], US) has been quick to emphasise, however, that ‘what [Colossal Biosciences have] done is create a grey wolf that superficially resembles a dire wolf’. Extracting genetic material from a tooth dated circa 13,000 years old and a dire wolf skull believed to be close to 72,000 years old is, itself, highly problematic with nearly 60,000 years difference between the two samples alone before considering the modern grey wolves used. In brief, with twenty distinct strands of genetic code identified via these sources, ‘[t]he genetic material was transferred to an egg cell from a domestic dog, then the embryos were transferred to surrogates for gestation and, finally, successful birth[s]’ (Besley, 2025).

In his critique, Lynch (2025) goes further to emphasis that this is merely ‘what we think dire wolves got have looked like’, with numerous other theorists echoing the flase sentiment of ‘de-extinction’; a challenge to co-founder Ben Lamm’s (2025) proclamation that the fact these three specimens have ‘super thick fur, their tail is a little longer, [and] they are taller’ than their grey wolf contemporaries somehow accounts to de-extinction. In their promotional materials, Colossal Biosciences (2025) drew parallels to a Jenga tower, where the loss of a species represents a block which, if removed, may cause the structure as it currently stands to collapse. This metaphor fails to recognise, however, that extinction is not a moment in time, rather, it occurs over an extended period in which populations diminish and rise, fluctuating for any number of factors that include habitat loss, hunting, and natural disasters.. As such, the sudden ‘re-insertion’ of a supposed replacement species is not a natural like-for-like process, but the conscious introduction of an invasive species – this being particularly true for creatures such as the dire wolf or woolly mammoth that died out tens of thousands of years ago.

The People Versus Ecocide…

Drawing on the United States Environmental Protection Authority (2024), McCarthy (2025) extends this commentary to modern habitat destruction, observing the havoc humanity has wreaked. Though McCarthy (2025) cites the increasingly poor state of open water swimming sites in Ireland, similar issues are witnessed in areas as diverse as the Colombian wetlands (Global Witness, 2025) and the Indian Konkan coastal ports (Global Witness, 2024a). McCarthy (2025) outlines the corporate and state acceptance – even if hit with fines (UK Government, 2023) – of waste being dumped in rivers, noting that ‘[r]aw sewage can lead to algal blooms that ultimately kill other marine life[,] block the light needed by underwater plants for photosynthesis [and] reduces oxygen levels when the algae die and are consumed by bacteria.’ Such actions have been observed consistently in recent years (BBC News, 2021), yet this awareness of these destructive actions have rarely been challenged. Where they have been, criminalisation and violence are commonplace (e.g. Rodway, 2024, Global Witness, 2024b), whilst radical actions are often limited in their circulation (see e.g. the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society [Siddique, 2010], How to Blow Up a Pipeline: Learning to Fight in a World on Fire [Malm, 2021]). This led McCarthy (2025) to conclude that ‘Under capitalism, there seems to be a disparity between this understanding of what needs to be done and the reality of what actions are taken’. The notion that de-extinction can revive any further damage caused to the natural environment and the creatures that live there will only lead to equally lax attitudes towards conservation. Easier to do what they want to now, and buy forgiveness later…

Given this, McCarthy (ibid.) promotes a dual focus that applies equally to the broader environment as to the free water winning context, arguing that ‘[w]e have a duty to stop the current environmental damage being done, but also to educate people on the importance of clean water so that those managing our water systems will be held accountable’.

Without an understanding of the spaces we inhabit and the extent to which those responsible for them are negating their duty (be that to the waters, land, or animals that live in them), it’s rare that this justified rage has the opportunity to manifest. It risks the same passivity expected of us under capitalism’s economic harms extending to the flora and fauna we live amongst. A critical consciousness – not mere criticality – can be achieved through sharing our understanding of the harms (giving voice to impacts of ecocide), leading to collectivised actions intended to limit the impact on habitats and the life within them. Hence Spear’s (2025) query when it comes to consuming the earth’s resources, ‘[a]re you fighting for your own plot of land or collective farming?’; co-creation and mutuality are fundamental to preventing further ecocide now that corporations can slap a dire wolf-shaped plaster on it. Conservation and protection, surely, are more vital now than forcefully inserting long absent species into ecosystems that have accounted for their disappearance.

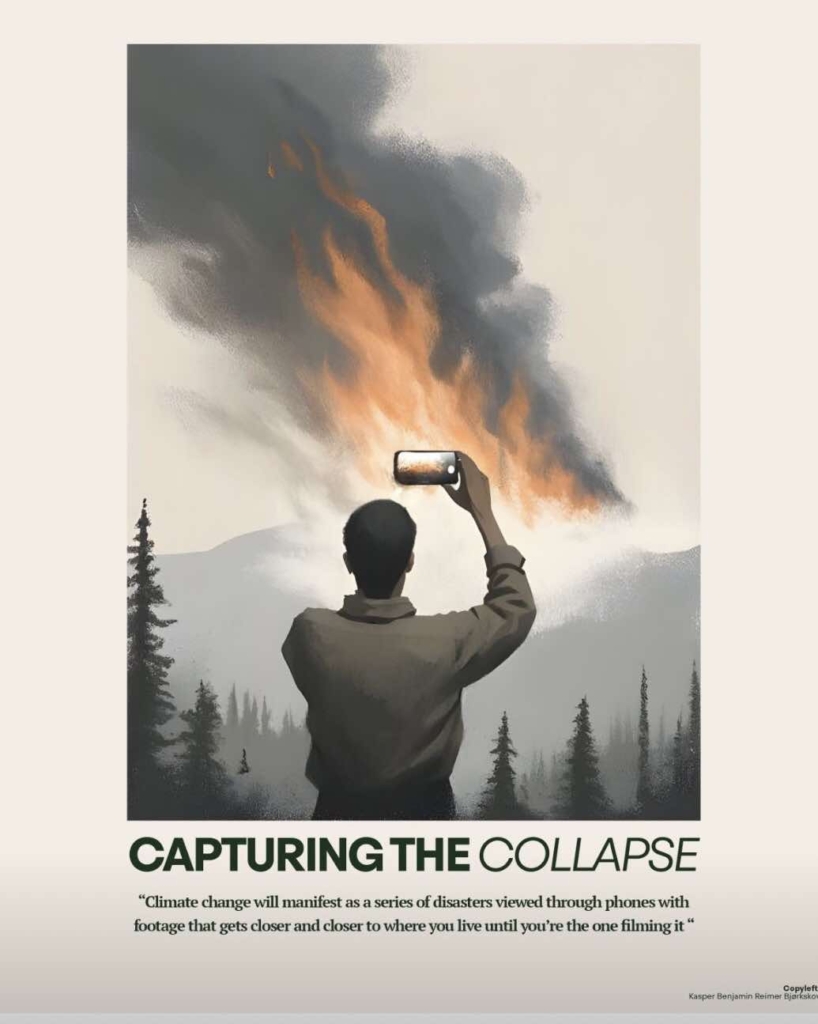

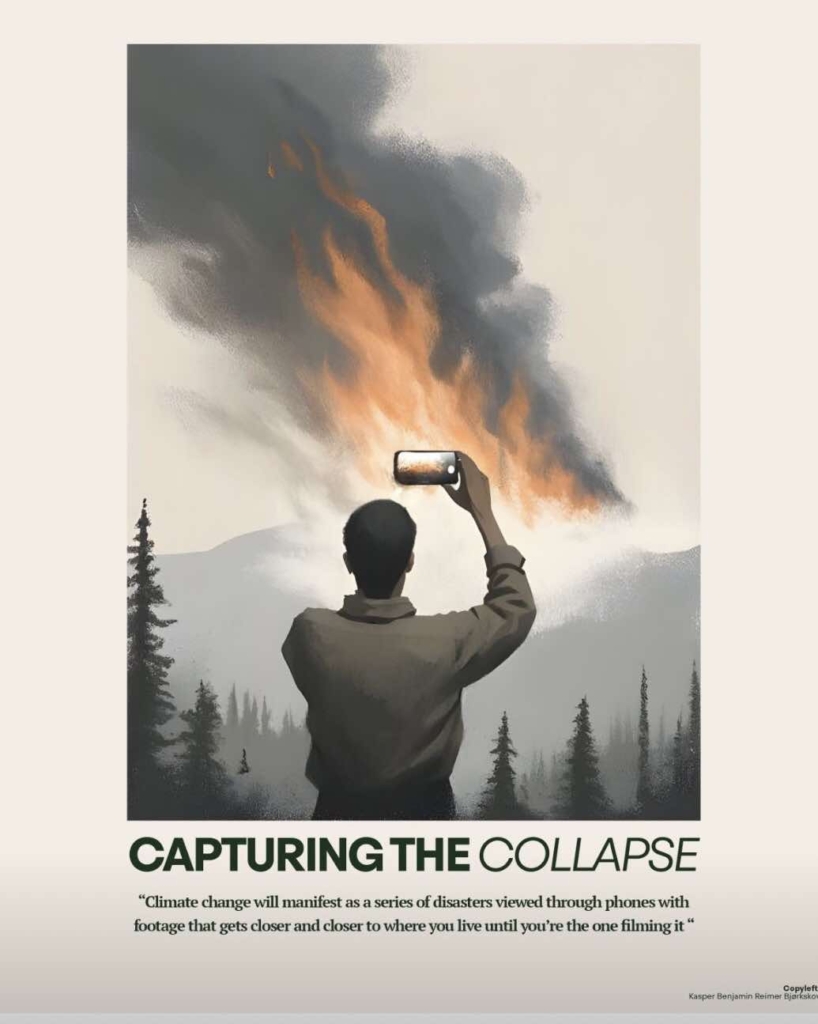

Species extinction is far from a new phenomenon, and few could feign ignorance of humanity’s impact, even when that stems primarily from the actions of a minority. Reflecting on Walter Benjamin’s life works, Spear (2025) repositions his explorations of crises in 1940’s Europe to today, recognising that ‘“[t]he single catastrophe” looks like a “chain of events” livestreamed to our phones: videos and images of extreme weather events, one after another, killer heat waves and deadly mass floods, and the genocide of the Palestinians. Unimaginable suffering in real time’. It’s echoes a comment a pal, @PerthshireMags, made some months ago on X (Twitter) that garnered hundreds of thousands of shares across the many, many iterations of it with and without credit: “Climate change will manifest as a series of disasters viewed through phones with footage that gets closer and closer to where you live until you’re the one filming it”.

For some, sharing footage of a ‘dire wolf’, a zebra bred to superficially resemble the Quagga, or an Asian elephant imbued with woolly genetics will surpass the loss of species – a vital hit that will make us forget the final paces taken by the Tasmanian Tiger – but we cannot fall for capitalism’s latest solution. Anything close to that is dishonest to ourselves and disingenuous to the world around us.

References

Adam, D., and Cole, C. (2010) Meerkats, chimps and pandas: the cute and the furry attract scientists’ attention and conservation funding. The Guardian.

Barnosky, A.D., Koch, P.L., Feranec, R.S., Wing, S.L., and Shabel, A.B. (2004) Assessing the causes of Late Pleistocene extinctions on the continents. Science. Vol.306, pp.70-75

BBC News. (2021) Staveley sewage discharged hundreds of times into protected river.

Besley, J. (2025) Scientists announce dire wolf species has been brought back from extinction after 10,000 years. The Independent.

Coleman, M. (2021) The Anthropocene and its Discontents. Rupture. Vol.5

Global Witness. (2025) Secretly filmed footage shows Veolia contaminating protected Colombian wetlands.

Global Witness. (2024a) The Emirati-backed oil project sparking conflict on India’s Konkan coast.

Global Witness. (2024b) More than 2,100 land and environmental defenders killed globally between 2012 and 2023.

Goebel T, Waters M. & O’Rourke D.H. (2008) The Late Pleistocene dispersal of modern humans in the Americas. Science. Vol.319, pp.1497-1502

Hester, J. J. (1969) Late Pleistocene Extinction and Radiocarbon Dating. American Antiquity. Vol.26(1), pp.58-77

Lamb, B. (2025) In Parkel, I. (2025) Game of Thrones author George RR Martin broke down in tears meeting ‘de-extincted’ dire wolves. The Independent.

Martin, G.R.R. (2025) In Parkel, I. (2025) Game of Thrones author George RR Martin broke down in tears meeting ‘de-extincted’ dire wolves. The Independent.

Martin, P.S. (1984) Prehistoric Overkill: The Global Model. Quaternary extinctions: a prehistoric revolution. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press

McCarthy, N. (2025) Swimming in Sh*t. Rupture

McCormack, O. (2023) Where now for the Climate Movement? Rupture. Vol.10

O’Keefe, F. R., Binder, W. J., Frost, S. R., Sadlier, R. W., and van Valkenburgh, B (2014) Cranial morphometrics of the dire wolf, Canis dirus, at Rancho La Brea: temporal variability and its links to nutrient stress and climate. Palaeontologia Electronica. Vol.17(1), pp.1-24

Parkel, I. (2025) Game of Thrones author George RR Martin broke down in tears meeting ‘de-extincted’ dire wolves. The Independent.

Rodway, N. (2024) Beware the criminalisation of environmental protest in Australia. Al Jazeera

Sandom, C., Faurby, S., Sandel, B., and Svenning, J.-C. (2014) Global late Quaternary megafauna extinctions linked to humans, not climate change.

Seymour, R. (2024) Disaster Nationalism: The Downfall of Liberal Civilization. Bristol, England: Verso

Shapiro, B. (2025) In Besley, J. (2025) Scientists announce dire wolf species has been brought back from extinction after 10,000 years. The Independent.

Siddique,H. (2010) Japanese whaling boat clash likely to ignite row over activists’ tactics. The Guardian.

Trimble, M. J., and van Aarde, R. J. (2010) Species Inequality in Scientific Study. Conservation Biology. Vol.24(3), pp.886-890

UK Government. (2023) Press release Unlimited penalties introduced for those who pollute environment. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs.

United States Environmental Protection Authority. (2024) The Effects: Dead Zones and Harmful Algal Blooms. In McCarthy, N. (2025) Swimming in Sh*t. Rupture

Veríssimo, D. and Smith, B. (2017) Even ugly animals can win hearts and dollars to save them from extinction. The Conversation

As bringing back dire wolves and mammoths or whatever has become venture capitalism, one can only deduce that even if successfully reintroduced to whatever wild is left, the only purpose of this whole charade is to make a lot of money charging people so they can hunt them. If they are being ‘nice’ they might put them in zoos and wildlife parks which can then charge extra entry prices for the thrill of seeing a captive animal walking in circles in an enclosure. Meh.

A has been pointed out elsewhere, they are not “de-extincing dire wolves”, because to become dire wolves they would have had to been allowed to group up in the environment that original dire wolves lived in. Same with mammoths et al. All species are functioning outcomes of their environment. Or in the case of humans, a disfunctioning species maladapted to the environment it has made for itself.

https://youtu.be/YBkl2kCdW-w?si=OLGhTJ0Lj6Smiq1D

As there appears to be no intention to recreate the habitat that dire wolves existed in, this is all just folly. People with too much money and a dispoportionate access to resources. Humans becoming gods trying to defy evolutionary process. A delusion of a delusion, making a parody of existence.

Can you imagine? In the UK there are people whinging about a few beavers being let loose, what would happen if a pack of dire wolves started rampaging around the Scottish Highlands or the North Yorkshire moors?

What a nonsense.

If they timed it right and a pack of dire wolves thrived just as humans went extinct, then it might be worthwhile. Please, all this activity, resources and energy should be used to prevent what’s left from going extinct, not that that is redeemable now, but they might slow down the process a bit.

I am no fan of unbridled capitalism but given such disasters as the diversion of the inflow to the Aral Sea or the “smash sparrows” campaign of Mao isn’t there another “c” word that should also be used here?

@Stephen Senn, I presume you mean ‘Communism’ rather than ‘Christianity’ or ‘Confucianism’? No need to be coy, surely?

Communism is basically sharing, and therefore can generally happen where sharing can. As in the management of commons. Global science is an example of idea communism, and is itself exemplified in the public sharing of genomes, which can occur in avowedly-capitalist USA as much as in avowedly-communist USSR or People’s Republic of China (where a lot of capitalism occurs in the flipside).

Many things happen in countries that are little or nothing to do with whatever the ruling class official denote their economic system as. Economic systems need hosts, and host societies come with a lot of shaping features and countercurrents, ideologies and biases, histories and hierarchies, in-groups and out-groups, friends and foes, technologies and geologies, biomes and climates, languages and stories, majorities and minorities, resources and curses, healths and sicknesses.

If communism is applied as a humanism, it won’t share the planet (equitably) with non-humans, who will tend to suffer as a result. If communism is applied in the context of nationalism, nations won’t share equitably with others. If communism is applied as religion (as in the early Christian Church), believers may not share equitably with those lacking souls or marked with unholiness. However, if communism is applied to the living planet, treated as commons for all lifeforms, then ecocide will be a paramount crime, and creating new invasive species by genetic gambling an act of war.

#biocracynow

The article raises important (vital) points and makes sound arguments that the ‘dire wolves’ story is public relations for another profitarian incursion upon the commons of our living planet. I would imagine, generally to prepare public opinion for more genetic gambling, and to assuage guilt over extinctions (hey, we can always bring ’em back) hence endorsing neoliberal exploitations, extractions, exterminations and enclosures. But as noted one of the real dangers is introduced species:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Introduced_species

which combined with genetic gambling will accelerate and warp evolutionary processes beyond ecosystem’s ability to cope: a biological arms race going supercritical. Humanity may be in need of a predatory species to keep its rampaging numbers in check (aside from the ancient ‘man is a wolf to man’ proverb), but it won’t be the dire wolf or tyrannosaurus rex. It may turn out to be something lab-grown for some entrepreneurial start-up, though. If we haven’t simply killed off our staple food crops by then.

Science fiction has produced many plausible scenarios.