Update from the Kurdish Liberation Movement

The first of a three-part series looking at the situation in the Autonomous Administration of North-East Syria (AANES), also known as Rojava.

The Kurdish Liberation Movement is entering a threshold period that could lead to a substantial redistribution of power in the Middle East. After the takeover of the Syrian state by the rebel group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in December, and as US presence is shifting in the region, new alliances have to be formed for this revolutionary movement that has been running the North-East of Syria autonomously and democratically since 2012. On March 10th, an agreement was signed between their military, known as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and HTS, opening the way for future collaboration — but many points remain uncertain. Ronahi Hasan of the women’s organisation Kongra Star in North-East Syria, commented on the new Syrian head of state: “Al-Jolani is not working in a democratic way … if things aren’t going according to the agreement, we will leave the agreement”.

For fifteen years, the Autonomous Administration of North-East Syria (AANES), also known as Rojava, has been functioning under a confederalist structure that places great importance on bottom-up democracy and local autonomy. This is the result of decades of struggle for liberation by the Kurds, an ethnic minority in Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. They have been the target of near-genocidal repression in all four of these states, in particular Turkey, where they represent a significant part of the population.

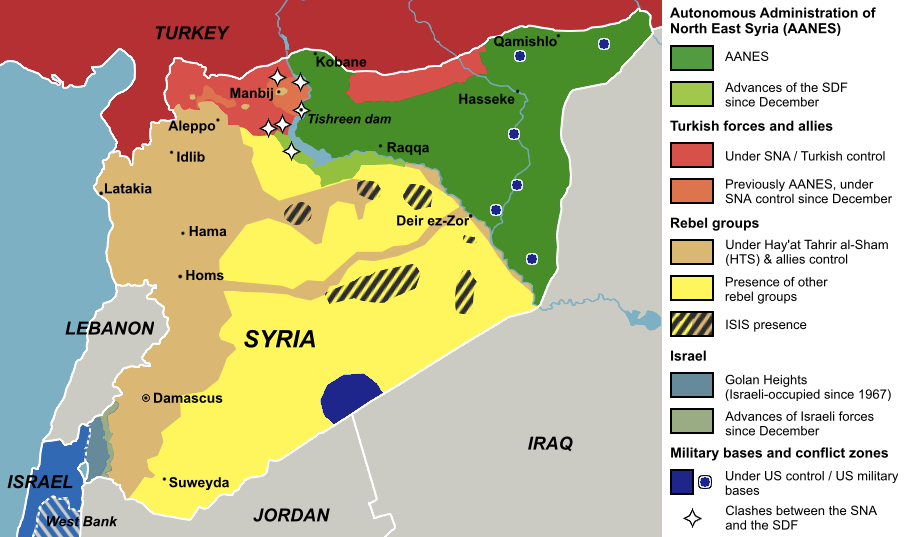

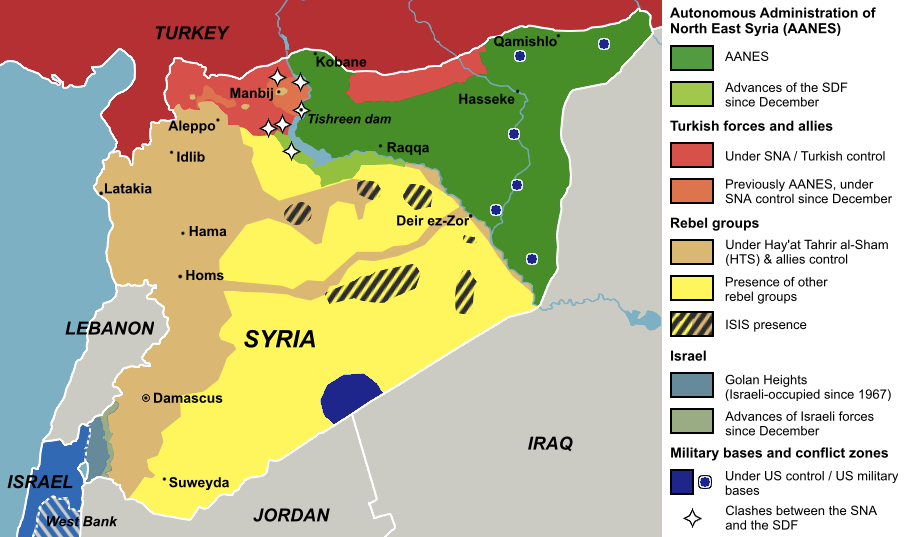

Erdogan’s war on the Kurds extends beyond Turkish borders, with constant military harassment of the AANES. This came to a head in December, as Turkish-backed HTS overthrew Bashar al-Assad’s regime and fights broke off all over the country, including at the borders of Rojava. HTS almost immediately gained control over the city of Manbij, previously part of the AANES. Clashes are ongoing between the SDF and the so-called Syrian National Army (SNA), which is in fact a group of militias directly funded by the Turkish government. They are particularly intense around the strategic point of the Tishreen dam near Manbij, which generates electricity for a large part of Rojava.

While the Assad regime was noted for its extreme authoritarianism and oppression of ethnic minorities including the Kurds, who sometimes struggled to even obtain citizenship, it was not in direct confrontation with the AANES. The rise of HTS deepens the hold of Turkey on the region, thus threatening the autonomy of the AANES and livelihood of its populations. As Ronahi Hasan reminds us, HTS is also an islamist group that is “not open to democracy, women’s rights, or the rights of ethnic minorities.” She insists that while the regime is being normalised by European government and press, the people of Rojava are not forgetting that HTS originates in Al Qaeda and has perpetuated massacres against Alawite minorities in the West of Syria less than a month ago.

The risks of radical islam are not taken lightly in Rojava, a region that has faced carnage under occupation by ISIS between 2013 and 2019. Their military forces, including the prominent women-only militia YPJ, fought ISIS and ultimately defeated them, with support from the USA. Since Trump’s first presidency in 2017, that support has significantly decreased. In an effort to disengage from the Middle East in general, Trump has just announced plans to completely withdraw US military presence in Syria within two months.

While it has been massively weakened, ISIS still maintains a presence in the region through sleeper cells, that are becoming more active since HTS installed an explicitly religious regime in Syria. Buthina Abod, the spokeswoman of the women’s organisation Zenobia in Raqqa, adds that ISIS mercenaries are “taking advantage of the situation now that the SDF is busy at the Tishreen dam”. YPJ commander Viyan Adar cites the 70,000 ex-ISIS fighters held in prisons across Rojava and asks: “If they flee and [the AANES military forces] are not here, what will happen?”

Three women from the women’s organisation Kongra Star posing in their office (Ronahi Hasan on the left)

The AANES is finding itself more and more isolated, opening the way for surrounding powers to take advantage of the situation and offer controversial deals. Despite historic alliances between the Kurdish and Palestinian resistance movements, Israel has hinted at the possibility of providing military support for the AANES. So far, the AANES has refused, but when I approached the subject with Avin Swaid, a high-ranking diplomat of the Women’s Department of the Administration, she replied: “When your back is against the wall, you take the help you can get.”

In this context, the agreement between HTS and the SDF is largely welcomed by the population and the Administration alike. Avin Swaid explains that “for fourteen years, [the AANES has] been looking for solutions and dialogue” with Damascus. This agreement, which is largely non binding but sets the objective of achieving a more detailed deal by the end of the year, could be the start of that process.

One of the main items of the agreement concerns an immediate ceasefire in the region. For Bushra Mohammed, the administrator of Zenobia, this is a huge relief: “There was fear of a military operation by HTS in the region [of Raqqa]”. However, she highlights that this did not put an end on attacks from the Turkish state, and she chastises al-Jolani for not taking responsibility for protecting peace in the region despite the deal. The agreement suggests that in the future, the Syrian military will play a role in protecting the AANES from Turkish attacks, but it remains to be seen how willing al-Jolani is to turn his back on Turkey. This also comes at the price of the SDF integrating the Syrian military, which could mean a significant decrease of autonomy for Rojava, and is at the heart of the ongoing negotiations.