The Juggernaut Can Be Stopped

THE JUGGERNAUT CAN BE STOPPED: Ewan Morrison on ‘For Emma’ & Resisting The Rise of Techno-Capital

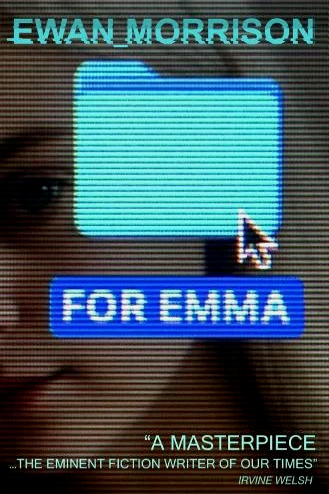

A conversation with Scottish literature’s enfant terrible about the themes of his new techno-thriller ‘For Emma‘, beamed to you from a dystopian near-future. By Bram E Gieben.

I enter the shabby hotel room a few minutes before the author Ewan Morrison arrives. He knocks and enters, and we exchange a wordless hello. Slowly, carefully, we each begin to feel around the room’s nooks and crannies, running fingers underneath the 3D-printed shelves and behind the smart wall’s glassy beveled edges.

Ewan disconnects all of the electrical devices from their sockets and takes a small screwdriver from the breast pocket of his blazer. With careful concentration, he unscrews each plug and checks the wiring, then replaces the outer shell, leaving the devices unplugged. I circle the light fittings, unscrew each bulb, and replace it with a fresh one from my pack.

It takes about ten minutes, then we each take a seat in two dilapidated armchairs, turning them towards each other. Ewan nods and I open my laptop, hit ‘RUN’ on a localised distortion field. Satisfied that we are hidden from the data-saturated environment, and free of listening devices, I hand Ewan a mylar bag. He takes the SIM from his phone and drops it in, I do the same. Finally we greet each other. We are here to talk about the singularity, and the eerily prophetic predictions of his 2025 novel, For Emma.

Just a few short years on from its publication, many of the novel’s technological tropes have become fact – from the implants that augment and monitor the brain functions of the majority of those now under 20 years old, to the exponential growth of surveillance technology and artificial intelligence in our digital devices, to the use of medical nanobots in our bloodstreams and neurons, to the implicit tightening and narrowing of free speech norms that attended the rise of digital states, and the emerging infrastructure of the UK’s social credit system.

What follows is a record of our conversation, and our hopes for the future beyond the horizon of the predicted singularity. We draw on banned works by Mark Fisher, Nick Land, John Gray, Nick Bostrom and others, burned in the great purge of 2028. If you’re reading these words, you are the resistance. Destroy this file after reading.

Bram E. Gieben (BG): The world For Emma depicts is one where corporate control and surveillance have penetrated every single facet of government, industry and culture. How far away did that moment feel when you wrote the novel?

Ewan Morrison (EM): People said, “Oh, you’ve written your first science fiction novel,” and I had to reply that I was still being a realist. The world has taken a turn into science and the fictions or ideologies around our big-tech future. The world has become sci-fi, and if you look into the big motivating idea behind AI, transhumanism and effective accelerationism (e/acc) in Silicon valley, it’s this belief in ‘Hyperstition’ – literally the belief that fictions can be made to manifest in reality if we believe in them enough and invest in them. Self-fulfilling prophecies.

These big tech gurus and their followers believe that they can force AI superintelligence and other imaginary science-fiction technologies to emerge via an act of collective faith, and by the whipping-up of hype to generate hundreds of billions in speculative capital to ‘make the fiction become real – to make the dream come true’.

It’s a Californian ideology that fuses the beliefs of ‘the law of attraction’ – as seen with people like Oprah Winfrey, and her belief in ‘manifesting’ wealth and health – and the old American Power of Positive Thinking, with the equally cult-like and euphoric tech utopianism that has grown out of Silicon Valley, and which is now articulated by tech gurus like Marc Andreessen and Elon Musk. Andreesen even wrote a techno-optimist manifesto. The result is that the fastest growing speculative economy in the world is now being led by science fiction, the acolytes who believe in it, and the investors who are duped by it.

As for the novel and the big tech within it, I didn’t invent anything new, I’ve only taken the tech that existed in 2025, and the euphoric future projections written by tech gurus like Ray Kurzweil, and the two co-founders of the World Transhumanist Association; Nick Bostrom and David Pearce. I subject them to hyperstition, so I allowed those technologies to emerge as realities in the novel.

We have a more advanced invasive brain chip technology, and the extensive human testing of nanobots as a health tool – that’s thousands of nanobots circulating within the human body with the goal of repairing tissue.

When I wrote For Emma, the widespread human testing of these technologies seemed maybe only five years away. Elon Musk said that he planned to have 20-30 human test subjects fitted with his Neuralink brain chips within 2025, let me just quote him: “There will be hundreds of people with Neuralink in a few years, maybe tens of thousands within five years, millions within ten years.” We shall see.

We should keep in mind (no pun intended) that this is a procedure that involves invasive ‘trodes penetrating the brain flesh itself, and that 4,500 lab animals died at the Neuralink Labs. Musk contests this and puts the number at 1,500. You could argue that the novel, since it deals with a young woman who dies from an invasive brain chip and nanobot experiment, is really about the consequences of what happens to us frail little humans, us nobodies, when the world starts to live by a vast fiction – a science fiction.

As for the other technologies in the book – by 2025, there are already hospital robots in China (China also has the world’s first AI run hospital), and pervasive surveillance technologies (London has the second biggest citizen surveillance system in the world). People consent to it, even enjoy self-monitoring.

People jogging happily wear devices that report their heartbeat, blood sugar, body temperature, geo-location and even their conversations back to central computer systems – whether or not they understood that they were feeding AI growth, and contributing to the building of the ‘internet of everything,’ the dataist worldview, and the ‘fourth industrial revolution’ – and of course helping to build the power base of the technocrats who want to reduce all human activity to measurable, monitorable and controllable data.

I have a question for you. Do you think that this big tech future in which we are all monitored and controlled by big tech algorithms is ‘fated’ or ‘inevitable’ as the tech gurus would like us to believe? Can the genie be put back in the bottle or do we just have to simply, passively accept this future, in which humans have less importance and less to do as the machines control more of our lives, and in fact enter our bodies?

BG: I like that formula you propose – that robber barons like Musk immanentized science fiction concepts that are neither good for the world, nor likely to be sustainable or viable in the long term. I’m not sure it’s inevitable in the sense that people fear – progress, like anything else humans create and drive, is very asymmetrical. As the global surveillance state emerges, run or powered by big tech, there are still many parts of the world it doesn’t reach.

A bigger risk, I think, is that the stratification of societies increased, along with inequality, as we have seen. Musk wanted a future where a select elite have access to the ‘benefits’ that technologies like Neuralink give them in a hyper-accelerated, technofeudal economy, while the rest of us remain unmodified “digital peasants”.

He got his wish, for the most part. But this attitude contains the seeds of its own destruction. I can still imagine a future where the techno-enhanced simply become irrelevant, because the rest of us are too busy running society and the economy. While the opposite may seem true now, that could change.

The more removed we become from our physical humanity, and the sense of ourselves as animals, the more abstract the problems we are likely to try and solve. So while Elon and the enhanciles are off attempting to control Artificial General Intelligence, we flatscans are starting to grow vegetables and live off-grid.

I see the latter as infinitely more appealing to most people, the more they are denied access to the so-called advantages of living in crumbling capitalist economies. If there’s a future that runs counter to the techno-utopian dream of progress, it lies in self-sufficiency. I often return to the fact that until the 1970s, Britain’s allotments provided nearly 20% of our food stocks. There’s potential to go back to that via projects like community gardens, or even vertical farms.

John Gray‘s view is that progress is an illusion of temporality. To any person standing in a certain era, looking back he will see progression from an antique past. Looking forward, he will see only the benefits of technological or social evolution. But over the timespan of just a handful of human lives, that unbroken line of progress proves to be much more faltering. There are reversals, regressions; leaps forward that seem judicious but prove disastrous. I wonder if our current drive towards the transhuman singularity is one of these regressions, if seen over a long enough timescale.

I wanted to ask you about theories of the ‘uncanny’ or unheimlich, as Freud proposed, and Mark Fisher later developed. At heart the unheimlich is about the familiar, made strange – perhaps the greatest source of fear. In what ways do the technologies proposed and developed by transhumanists leave us in an uncanny world? Will a more automated, simulated future free us from labour, or leave us in horror?

‘How can we just sit around waiting for society to crash in the hope that something better will come after it?’ – Ewan Morrison, Writer. (Photo credit: Angela Catlin)

EM:I’m glad you brought up Mark Fisher. He’s an important thinker who has been influential for both of us, and many in our generation, and the next. I latched onto him through his analysis of cultural stagnation and repetition in the 21st century. The sense of what the late great Lynda Obst, the movie producer called sequelitis – we’re trapped in sequels, remakes, reboots, and best-ofs, and this extends well beyond movies into books, music, even academia.

Everything repeats but there’s no real sense of forward momentum and eccentric, rapid invention and erupting crazy creativity as there was in the 20th century. All our present-day technologies are iterations of earlier innovations. As Fisher said (I paraphrase here), 21st century culture is 20th century culture ‘on higher-definition screens.’ There’s so much evidence of that, and this ties in with his Neo-Marxist analysis of what he would call late capitalism or Capitalist Realism, and “the slow cancellation of the future.” I think we’ve both been influenced by this insight.

And Fisher, to his great merit, found artists and musicians who reflected this sense of being trapped in a repeating time loop. He introduced me to the music of Burial and The Caretaker, for which I am eternally grateful. All good so far, and that’s because Fisher here is in diagnosis mode, but where I part company with Fisher is when he tries to move from diagnosis to strategy. From ‘these things are broken’ to ‘here’s how we can fix them.’

This is a common problem that plagues the entire history of left-wing thought, and that used to bother me when I was a card carrying communist and later a neo-Marxist and even Post-Marxist, like Fisher was. The big question after so much analysis and eventual analysis-paralysis is Lenin’s question: ‘What is to be done?’ This question plagues us as artists in the 21st century in this time of stagnation and repetition. Should art even be done?

I was here in Glasgow when the Berlin wall fell and the USSR collapsed, and I vividly recall being dragged into the farewell party of The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). It was a room in a dark, damp little place near the arches under the Glasgow Central station railway bridges. Free drinks were on offer, and ten old folks, true old school communists in their late 60s, were either sitting around drinking alone or were dancing to this squeeze box accordion.

It was like a scene from a Béla Tarr movie, and I was the young man getting burled around by the matronly old Stalinist who yelled out dancing instructions. It was surreal, and wild and drunken and sad. The thing they believed in all their lives had collapsed. Communism, as they saw it, had died. The idea of the planned economy which was the true foundation of Marxism had failed and to their merit, rather than shackling themselves to New Labour, or the Fabians or the postmodern / Maoist / deconstructionists, or what would in five years time emerge as identity politics, they decided to disband. True old school communists, faced with facts. They went down with the ship.

I mention this because I think that whether we like it or not, that great failure still haunts what became of the left to this day, and I think it contaminates and ruins Mark Fisher’s plans for ‘what is to be done.’ I also believe it explains his interest in ‘the uncanny.’

When Fisher is talking about the sensation of the uncanny and the weird (our sense of disgust and fright when we come across mannequins, dolls, and creatures that are augmented with machines), he’s using this to critique Freud for being a dusty old conservative. Fisher is trying to depict the uncanny as having the potential to ‘disrupt’ normalcy, to smash conventional society.

And so, I think Fisher is stuck in a very old pre-‘fall of the wall’ habit of trying to disrupt capitalism, trying to cause it to collapse, looking for cracks in the structure. He will unleash the freaks and weirdos of the uncanny, the cyborgs and the half-humans who make us shudder. But I’m afraid it’s all just a nostalgic replay of the early days of Marxism, a call to create a new revolutionary class, but this time not from the proletariat, but from the misfits, the dolls, the automata and the imaginary transhuman and posthuman beings of the future. When ultimately, the fact is there – the planned economy failed.

The only other option for communism is Maoist China. The hybrid control economy, the surveillance state. So much else that the left has done since the fall of the Berlin wall is just going through the motions of acting out old forms of subversion, habits that haven’t died, resentments that haven’t died out. But to what end? China is the only hope for communism. Face that fact, or go down with the ship.

I’m always conscious when talking about Fisher to pay him his dues – and to pay my respects, as he committed suicide in 2017, and we’re worse for the loss of his brilliant mind. But his idea of the uncanny is tied to this belief in tech accelerationism that he never shook off, and that is a problem.

Today, we associate accelerationism with big tech and mostly with the right-wing libertarians of America. You hear accelerationism coming out of the transhumanists, the tech utopians, the e/accs and the neoreactionary NRx trolls. You hear its sci-fi-fantasy ideology in the mouths of people like Musk, and even J.D. Vance.

The big idea is that you accelerate technology to ‘escape velocity’ where it escapes all regulation and control by the state and achieves a breakthrough (the singularity), after which an entirely new civilisation is created by superintelligent tech. It’s a liberation from which there is no possible return.

And, of course, Fisher was deeply involved with the leading accelerationist, Nick Land, at the experimental, radical Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU) in the 1990s in Warwick and they then parted company, around 1998-2004 – they are the two sides of accelerationism, left and right.

Today, we see Land as one of the leading ‘Dark Enlightenment’ philosophers of neoreaction, and what he says is terrifying. He claims that capitalism and technology have fused, that acceleration can’t be stopped and that “nothing human makes it out of the near future” – meaning that we’re heading into the singularity and this will be a deregulated, chaotic, tech-led world in which none of the left wing goals survive, and even humans will become augmented by technology or bodily products on the cybernetic meat market.

So basically, Fisher went along with that dystopian vision half of the way, but then decided to break with Land and take the accelerationist idea and put a left-wing spin on it. If you like, he took the out-of-control juggernaut and planted a red flag on the roof. In Fisher’s version of the accelerationist apocalypse, some good can come of it because the techno-capitalist juggernaut will crash and then after that, from the ruins, something better might be built using technologies that free us from labour, that provide us with Universal Basic Income.

I think he’s wrong and he’s trying to, in story consultant terms, ‘nail an unearned happy ending onto a tragedy.’ Again, this takes us back to his suicide; hellish to speculate on it, but I’m haunted by the idea that Fisher might have realised that his belief in a left-accelerationist project was doomed to fail.

How can we just sit around waiting for the acceleration of tech society to crash in the hope that something better will come after it? That’s not doing or acting, it’s sitting on our hands and hoping. The desire for benign technologies emerging is not anything substantial to pin our hopes on. It’s like sitting around hoping that the coming future is more like automated UBI than Judgment Day in Terminator.

My only answer to Fisher and Land is that they’re both wrong. The accelerating juggernaut of techno-capital can actually be stopped, or has to be. That will take a lot of effort and resistance, but artists today are at the cutting edge of that – hacking through the fuel pipes and the radiator of the speeding juggernaut.

We have to get it to stop or at least to slow down, because we can’t place our trust on some fated apocalypse that will, as if by magic, create an opportunity to make things better. And we should definitely stop thinking that embracing the weird or the disruptive, subverting capitalism and so on is still an effective strategy for artists. The enemy is much bigger than that and it has only recently revealed its true scale. Accelerating techno-capital is the great disruptor and destroyer. The question then becomes what we can hold onto as we try to slow down the machine.

As my finger hovers over the ‘Send’ button, ready to disseminate this conversation across the interconnected webs of data and technology that make up the substance of our reality, Ewan and I hear the sound of heavy footsteps, jackboots in the hall. I execute the command, sending the conversation into the digital ether.

If you’re reading this now, the plan worked. I type in a string of old-fashioned green ASCII code into an open DOS window just as the door explodes inwards in a hail of splinters and steel. A gas canister spins and blooms, filling the room with acrid smoke. Green laser beams cut the choking air like knives. Voices shout and command. We scramble from our seats and retreat to the back wall, hands raised in surrender. I watch as the laptop bursts into flames, sizzling and bubbling, fusing the hard disk and plastic into a solid lump of slag.

We hope this conversation reaches you. We hope it changes you. Despite it all, we hope.

For Emma by Ewan Morrison is available now from Leamington Books.

The Darkest Timeline by Bram E. Gieben is out now from Revol Press.

This is part of a collaborative project between Glasgow Review of Books and Bella Caledonia. The Glasgow Review of Books is an online journal which publishes critical reviews, essays and interviews as well as writing on translation. They accept work in any of the languages of Scotland – English, Gàidhlig and Scots.

Brilliant piece Bella.

Fascinating idea, that the death of Communism (really?) has led to the dilution of left wing – ism.

Societal divisions in the techno-state will heighten as the technology is deployed.

Anti-robot forces will grow as humanity realises it is being strangled.

Is this time to live, exciting and hopeful or scary and fearful.

I guess it depends on whether our collective human cohesion can withstand the onslaught of

over-rich and powerful technocrats.

No, what has happened is that idea communism has become the most successful economic mode ever, and capitalists have tried with some success to exploit it.

https://blog.sleepingdog.org.uk/2019/10/three-communisms-that-shape-our-modern.html

We can see this everywhere. The whole AI machine-learning from Internet art rip-offs, the slightly older USAmerican attempts to seize global copyrights, digital news aggregators, the wholesale data thefts are just examples of friction where there were some barriers to fully-realised commons.

The material world is going in a similar direction in zones like the UK’s public spaces, if the article I read today about local park commons being privatised for summer festival season, and Bella’s coverage of Edinburgh, are indicative.

Most of our culture is based on such idea commons, which is why we see so much resemblance within genres, between literature and folklore, animation and games.

SD

Please let us have a clear definition of the word Commons that you constantly repeat.

It just seems rather unclear to me.

@Peter Breingan, by ‘commons’ I mean the usual (what Wikipedia calls ‘political economics’) sense:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commons

It’s worth checking the Marx and Engels description of ‘bourgeois’ world literature as such as commons (of ideas, at least).

My point is that capitalism is typically parasitic towards communism. Whether any modern nation ever adopted communism as their main economic system seems beside the point, especially given that any nation governed by a party calling itself ‘communist’ was immediately under attack/siege/vulnerable to covert destabilisation or over economic warfare. You probably aren’t inclined to share all your ideas, means of production and resources with your enemy. But many economic forms can coexist within one nation. The danger is that capitalism tends towards killing the goose that lays the golden eggs.

Thanks for this. Techno-fascism is like the dinosaurs: heavy armour, small brain, died out.

t seems to me that a 20th c Marvel Comic / Orwell / Huxley vision of the future is playing itself out. Although it has moved certainly on -the neofascist cones in a business suit or a T-shirt rather than a military uniform and the jackboot for example is so 20th c. We have much more subtle methods of control now – the Chinese call it social credit. People can find themselves isolated, bankrupted, unable to go anywhere or do anything, even identify themselves, without digital approval. Remember, ‘You’ll own nothing and you’ll be happy’. And a heart attack can happen to anyone, anytime.

It is nevertheless collapsing under the weight of its outdated 19th / 20th c ideology. The real world simply doesn’t work like that.. The planet is not a computer, but a living ecosystem. It cannot be ‘reset’.

After a few thousand years of growing, fear-driven addiction to power over other people and things, driven by an increasingly desperate need to dominate or submit to domination, we have finally reached a singularity. Power over (might is right) will now inevitably be replaced by power with, i.e. co-operation. Because there is really no alternative. Power over is inevitably destructive. And the internet cannot ultimately be centrally controlled – which terrifies them. Peer to peer networking, and nee ways of delivering privacy are unavoidable. As are disruptive cyber-attacks especially with the arrival of quantum computing. It will become impossible to enforce a monopoly on anything – patent rights, weaponry, etc. The only way to safety and security in future will be through negotiation and co-operaton. Those who live by the sword die by it.

From the first stone tools to AI, technology development has always been about exerting power over someone or something. Generations of people have tried to fight and control their fears of injury, thirst, starvation, sickness, old age / vulnerability, and death (fears common to all living beings). They /we have gone for protection to those we think can deliver it. And mostly they have relied on technology and psychology to try to deliver it. Power has to be given, it depends on more than the consent of the governed, it needs to deliver something – at least a sense of safety if not happiness. This means that many, perhaps most, power structures are forms of protection racket. Project Fear has deep roots. But technology can empower all and make the dictator redundant.

If you fail to satisfy hearts and minds, you create opponents. If you automate your friends you set yourself against real living people with real needs. For all their fancy weaponry the Americans lost the Vietnam War, the Afghan war, and they are losing in Palestine. and elsewhere. The days of the unipolar (or even tripolar) world are over And the more you have, the more you have to lose and the more dependent, desperate and fearful you become. You cannot keep control indefinitely or prevent your technology falling into the hands of your enemies – nor just other would-be dictators but ‘rebels’, ‘terrorists’, and so on too.

Explosives first appeared in Europe in the later medieval period. They were only available to kings and overwhelmed opponents. . Soon however guns became available. Arms races developed. Eventually we reached the point when nuclear weapons demonstrated that the powerful are willing to destroy the entire planet – if they can’t have it, nobody will.

The power-mad are now so deeply in love with technology the trans humanists even want to become digital beings themselves. It doesn’t appeal ro me. We are all interdependent elements in a planetary ecosystem. We are alive. We have agency.

Artificial intelligence is no intelligence at all – as investors are starting to discover. It is a way of avoiding responsibility spreading confusion and destroying meaning. And it can and will be used against its creators

The world really works as interlickung ecosystems that cannot be centrally controlled. Or switched off.

A centralised Internet of Things will always be subject to contested control. It will use so much energy as to be completely unsustainable. And it will be vulnerable to hacking and sabotage. Electrical radiation is also a harmful pollutant we have hardly started to study. But we now have technology to turn ‘power over’ on its head, decentralise everything, and work with nature rather than against it. Small is beautiful. It’s all about intention.

The dystopia depicted in the article here lacks intelligence, and relies on a vast planet-destroying infrastructure. Nobody really wants it because it is based on fear and cannot make anyone genuinely happy. And all those transhumanists? Pah, just cut off their power supply., and grow and enjoy some real food , real sunshine, real fresh air and creativity they can have no conception of.

Ewan is right about AI, the tech bros’ dystopia already kinda being here, I think that’s true, certainly in the case of mass surveilance, but it has to be said, the complicity of the mainstream media, as ever, in anything Power and Money tells them to think is amazing.

I read the other day in the FT – which as Chomsky rightly says, is probably the best newspaper available for informative news and analysis these days – that AI contributes the same amount to global warming as the aviation industry.

Who knew? How come that’s not a story for the Herald or the Scotsman or the Guardian even? How come we are constantly receiving this onslaught about how AI is a great thing we have to buy into, even if it costs us ours jobs? AI is the enemy extractive capitalism is the enemy, that the nation States of Europe are going along with it only proves who dumb they are… people don’t want driverless buses for example…

At the very least, people – like Pat Kane for example, a self-declared fan – should know that if they use the Chatbox (which is shite) they are contributing to global warming.

On the other hand, I don’t agree with Ewan that it’s a question of western capitalism or communist China…

Marx and Marxism come from a very long line of radical thought in Europe and America. There is a whole tradition starting from at least Rousseau and the American Revolution and has all kinds of different strands to it. Marxism – Marx as opposed to too many of his heirs – is an emancipatory doctrine which argues that it is the material conditions of life which determine social relations and that the promise on offer is to move “from the realm of necessity to the realm of freedom”, that is, once people’s basic life needs are met, we can truly fulfil our human potential (each in his / her own way)..

That is still valid for me today. What has gone for ever is messianic Marxism, or Hegelian Marxism, or (pseudo) scientific Marxism, whereby the so-called “laws of History” meant that inevitably, the proletariat, due to the laws of History and class struggle, were destined to usher in the classless society and a kind of left wing version of “the end of History”. These grand narratives that explain EVERYTHING were a feature of the 19th Century, but no one can take them seriously now…

In terms of films and “sequelitis”, this is probably the best time there has ever been for film-making. There are so many wonderful directors out there, from all over the world, that you just can’t keep up. Hollywood is a different story, it is in a creative crisis and has been for many years now, but the problem isn’t a lack of good films, the problem is they rarely make it to the big screen…

Anglo-Saxon capitalism is so ideologically driven that we can’t see all these great films that are out there on cinema screens because they are taken up with sequels, and remakes, and franchises…

We really do need a Scottish Film Institute, a cinematech with a couple of screens, a small library, a cafe, and a space for meetings and talks… They have these things all over the rest of Europe…

I mean, Western culture, to a large extent (albeit not entirely) is built on the culture of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. Well, for the Greeks, the only way a human being can fulfil himself is in the community, in the polis, that is, with other human beings.

So, this idea which is the most paramount idea in our society today, that we can fulfil ourselves purely as individuals is something which goes completely against the grain of what the Greeks thought… they would not have recognized that as “the good life”, which they believed was the goal of life, to live the good life…

And we know for a fact, from books like “The Spirit Level” (Pickett and Wilkinson), that people’s happiness is not affected by more wealth. After a certain amount of wealth, more money make no difference to happiness…

Even under capitalism in past centuries, you had communities, working class solidarity for example, but also the church, but these things are all gone or going….

So, I think you need to rebuild the idea of a community, a polis and an agora (meeting place or market place).

It’s a massive challenge but it’s the only way. What do we have under indiviualistic monpoly capitalims? Sky-rocketting mental health problems, unbelievable school absenteeism, violent, pointless knife crime, huge addiction problems and mass apathy… despair in a word…

I certainly believe there are much better alternatives out there, of course there are…

As for John Gray, and I’ve only read “Straw Dogs”, well he follows in a long line of English philosophers (and Scottish ones like Hume) in that he is a sceptic, his work is all about puncturing big ideas, and pouring cold water on anything that smells like Theory and, of course, there is nothing new at all in the view that History is cyclical, the Greeks thought as much, as did Vico and, say, WB Yeats…

So he is the heir of Hobbes and Locke and David Hume, at least in his radical scepticism, and that is the main vein of philisophy in Britain, scepticism and rationalism, a totally different tradition to continental philosophy…

But Frederic Jameson would say, for example, that you find continually in culture, expressions of a desire for utopia in human beings, utopia is always just out there ahead of us, and you find it in things like Hollywood movies: what is the traditional romantic comedy but a kind of utopian version of relationships and love? There are examples of it everywhere you look in Hollywood movies…

So it seems clear humans have a kind of desire for utopia inherent in our nature, though of course History shows that it can all too easily turn into its opposite, a nighmare…

In any case, in Britain, we are much further down the road to 1984 than most countries are… this is the most capitalist country in the world, along with the USA, profit is everything, money is everything, class is everything… and our democracy is really a very narrow and stultifying oligarchy

No wonder they kind of turn their noses up at us slightly in the south of Europe (Spain, for example), and they do….