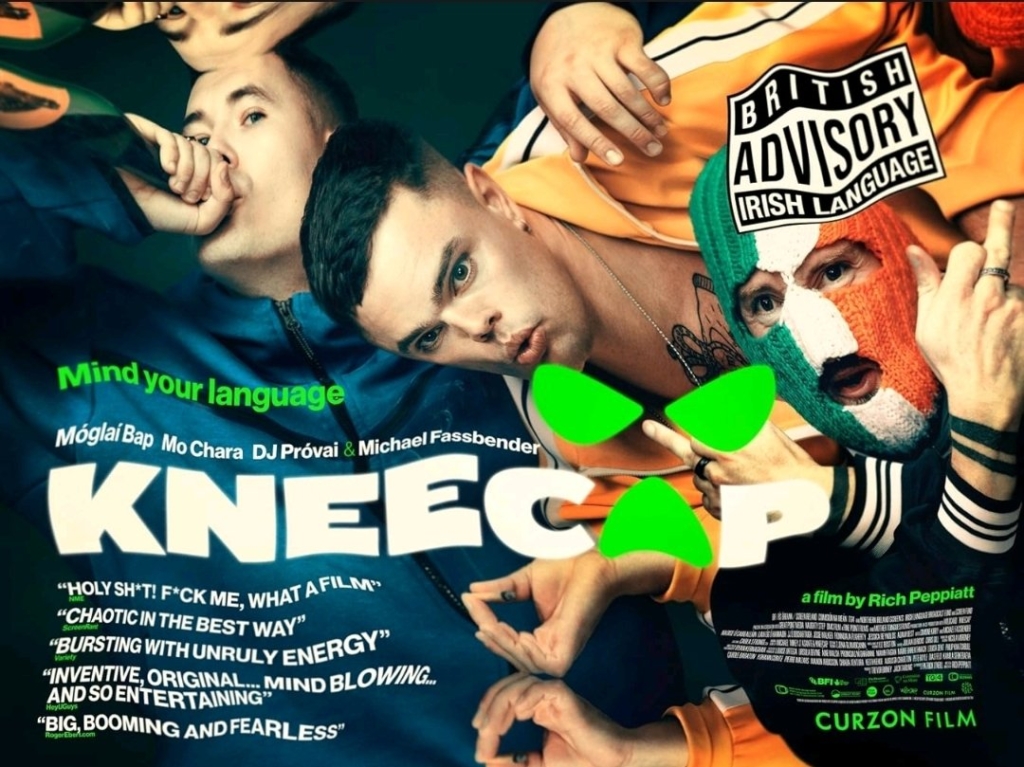

Behind the British State’s War on Kneecap

Last week, Liam Óg Ó hAnnaidh was charged with a terror offence by the Metropolitan Police. A member of the Irish band Kneecap, the Met allege that Óg Ó hAnnaidh, who performs under the name Mo Chara, waved a Hezbollah flag “in such a way or in such circumstances as to arouse reasonable suspicion that he is a supporter of a proscribed organisation” on stage last November. Denying the offence, Kneecap accused the British state of “political policing” and committed to vehemently defend themselves.

This development marked only the latest escalation in the establishment’s determined campaign against the Irish rappers, who have sat squarely in their crosshairs for years. In 2019, posters for Kneecap’s ‘Farewell to the Union’ tour outraged Boris Johnson’s Conservative government. Four years later, as Secretary of State for Business and Trade, Kemi Badenoch withdrew a sizable arts grant from the trio, only for the new Labour government to later settle the matter in court and award Kneecap £14,250 — the same amount they were initially granted.

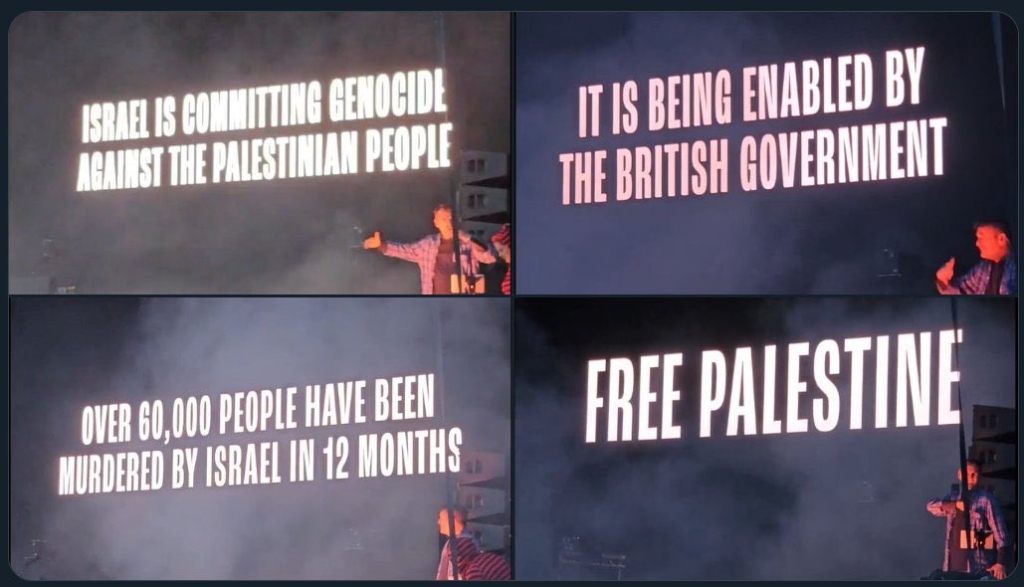

Establishment denunciation of the band, however, has intensified drastically in recent weeks following their appearance at the Coachella music festival in California. Leading a sea of fans in chants of “free, free Palestine”, Kneecap displayed graphics reading “Israel is committing genocide against the Palestinian people” and “It is being enabled by the US government who arm and fund Israel despite their war crimes.” Five weeks later, ahead of a summer of major performances (including Glastonbury), news broke of Mo Chara’s charge.

In his seminal history of the Haitian revolution, ‘Black Jacobins’, C.L.R. James wrote that, “when history is written as it ought to be written, it is the moderation and long patience of the masses at which men will wonder, not their ferocity.” Whether it’s popularising knowledge of the British Empire’s crimes in Ireland or Israel’s settler-colonisation of Palestine, Kneecap’s members tell history as it ought to be told everywhere they go and at any opportunity they get. In the heart of empire on one of the world’s largest stages, that’s exactly what they did — and that’s exactly why Mo Chara may now face prison.

In recent weeks, Keir Starmer’s government has begun to, in rhetoric alone, walk back its outright support for Israel’s crimes. Swathes of the British press have followed suit. As enforced starvation claims dozens of Palestinian lives every day, the establishment’s position is crumbling amidst sustained popular pressure. Even the BBC now runs headlines like “Israeli strike kills dozens sheltering in Gaza school”. However, as the concerted effort to cast Mo Chara and his bandmates as terrorists reveals, these crocodile tears barely disguise the British state’s contempt for those who dare to point out their complicity.

Its words may be warmer, and its statements may be stronger, but the British government would still rather pursue the opponents of ethnic cleansing than its perpetrators. Since Kneecap defeated the government in Belfast’s High Court last November, Britain has exported thousands of munitions to Israel and flown countless RAF reconnaissance flights over the Gaza Strip.

Today, even as politicians and the press seek to distance themselves from the war crimes for which they have spent years manufacturing consent, the establishment reserves almost unique resentment for an Irish rap trio from West Belfast. That’s because, while the mainstream media may be content to allow our politicians to wash their hands of their role in arming Israel’s genocide, bands like Kneecap will not. For the British ruling class, who have successfully managed most dissenting voices out of the cultural mainstream for decades, that is a particularly concerning development.

In 2014, Ed Sheeran devoted a rendition of his hit single ‘The A-Team’ to David Cameron during a private performance at which the then-Prime Minister was present. “This one’s for David,” said Sheeran, who was at that point the most-streamed artist in the world. Popular culture has always been an important terrain of political and ideological struggle, but this incident was emblematic of the extent to which neoliberalism had changed that.

Rarely, over the last quarter century, has Britain’s mainstream cultural sphere been the site of political contention. Amidst the triumph of Thatcher and her ideological inheritors, dissenting voices dwindled as the institutions of the social democratic settlement that once enabled countercultural outbursts, from affordable housing to free music tuition, withered. As Ed Sheeran unwittingly confirmed, a monochrome popular culture divorced from the lived reality of those who consumed it was the consequence, much to the delight of the elite who could afford intimate access to Britain’s Prime Minister and the world’s most-streamed musician at the same event. This pop-cultural blockage and the consequent reproduction of ruling ideology was, for Mark Fisher, a central tenet of capitalist realism.

Indeed, artists of earlier generations reacted very differently to David Cameron’s praise.

Informed that the Jam’s Eton Rifles was the old Etonian’s favourite song, Paul Weller asked, “which part of it didn’t he get? It wasn’t intended as a fucking jolly drinking song for the cadet corps.”

Kneecap, however, are different. They offer a horizon for cultural production which extends beyond the parochial, confronts the powerful and challenges their audience. In their songs, interviews and performances, the band foregrounds anti-imperialist politics, and they do so successfully. Not only did the Kneecap’s debut film pick up a BAFTA earlier this year, but streams of their catalogue have soared as the trio continues to make headlines around the world.

This is the intractable problem which confronts those who would see the group barred from every stage in the land: Kneecap sit at the forefront of a broader and increasingly vocal cultural milieu.

The horrors of Israel’s genocide, and the strength of the global popular movement to end it, have roused a host of mainstream artists to signal their solidarity with the people of Gaza. “The Nakba never ended, the coloniser lied,” rapped Macklemore to his 32 million Spotify listeners in his May 2024 single HIND’S HALL. Collecting the Best Album gong at last year’s Rolling Stone UK awards, Fontaines D.C. did not mince their words. “Free Palestine. Fuck Netanyahu. Fuck Zionism,” declared guitarist Carlos O’Connell from the podium. In April, even Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong appeared on stage wrapped in the Palestinian flag.

The point is not to overstate the importance of the kind of symbolic intervention listed above — of which there are a myriad of examples — but rather to highlight a more general cultural shift which, try as they might, the British state and its allies cannot repress. After 500 days of genocide and more than 186,000 deaths, locking up its leading advocates in the cultural sphere will not quell support for the Palestinian cause.

Indeed, attempts to do so must be viewed in the broader context of widespread state repression of the anti-war movement. In January, the Metropolitan Police violently arrested at least 70 anti-war activists during the first national demonstration for Palestine of 2025. Among those charged with public order offences were Ben Jamal, the Director of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign, and Chris Nineham, the demonstration’s chief steward. Both Jeremy Corbyn MP and John McDonnell MP were interviewed under police caution in the following days.

Acting with the explicit support of the Home Office, this authoritarian police response marked yet another advance in the British government’s long-running campaign to curtail the right to protest. In this case and that of Mo Chara, the long arm of the state was deployed to crack down on popular dissent to protect a historically unpopular government from mass confrontation. If the periodic intrusions of the public into the political arena — be that at a music festival or on a march — can be constrained, then it will remain exclusively the domain of the ruling class, insulating Keir Starmer’s political decisions from potential challenge.

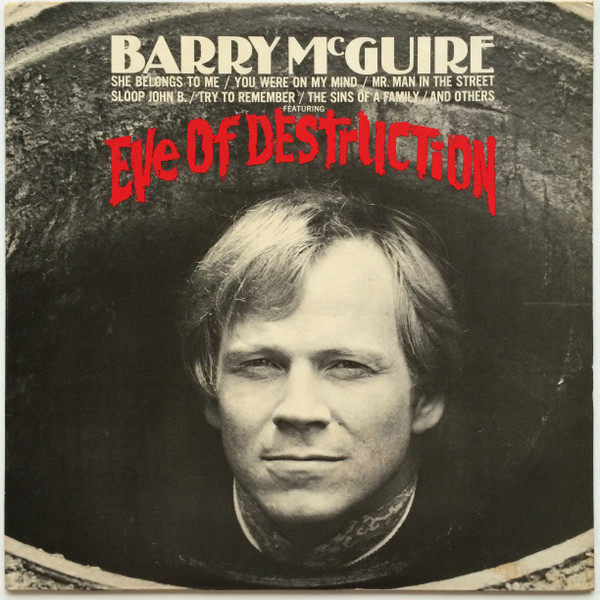

Kneecap, of course, are not the first musicians to face censorship for their opposition to Western wars. In 1965, while the Johnson administration doused much of Southeast Asia in poisonous chemicals, Barry McGuire’s recording of Eve of Destruction was banned across the United States. “You’re old enough to kill but not for votin’,” sang McGuire in an anthem that proved an instant hit with young Americans opposed to the Vietnam draft. Across the pond, the song was placed on a “restricted list” by the BBC, who, just a decade later, banished the Sex Pistols’ ‘Anarchy in the UK’ and ‘God Save The Queen’ from the airwaves entirely. Even Abba’s Eurovision-winning single ‘Waterloo’ was banned by the broadcaster during the first Gulf War as it sought to exhaustively police any music which might ignite opposition to British foreign policy.

Viewed in this context, the severity of the charge brought against Mo Chara represents a major intensification of state repression and exposes the political underpinnings of Britain’s “anti-terror” laws. In 1992, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary John Woodcock admitted that, “the police never were the police of the whole people but a mechanism set up to protect the affluent from what the Victorians described as the dangerous classes.”

Today, it is Mo Chara, his bandmates, and the wider Palestine solidarity movement that form the ranks of the “dangerous classes” and who, consequently, deserve our unwavering solidarity.

Mar a bhí riamh, mar a bheas go deo…

Ach ‘s fhèarr leam – Sin mar a bha, ‘s mar a bha ach seo mar a bhios

Duilich – Ach ‘s fhèarr leam – Sin mar a bha, ‘s mar a tha ach seo mar a bhios

Some similar points are made by historian Paddy Docherty in the book Blood and Bronze: The British Empire and the Sack of Benin (2021) that I’m reading now. There’s a particularly disturbing echo in the account of British colonial soldier-diplomat-administrator Claude MacDonald who was responsible for the ‘outrage’ of the blockade of Opoba, where in his own quoted report six years later (note the passive tense):

“many women and children died of starvation or were drowned in trying to escape from the starving town”

That is, a British officer using starvation as as act of unprovoked war on a helpless people they were legally supposed to be protecting, under the pretext they were inhibiting free trade (in fact the British were the ones enforcing tolls and trade restrictions, but hey, hypocrisy, cant and starvation of civilians is the British way).

Docherty notes that as usual the atrocities were kept out of British imperial accounts, and the British press were less than sympathetic to the plight, customs and rights of Africans.

https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1889/mar/28/west-africa-opobo-and-agenni-creek