Gaelic in the Digital Age: Inside the ÈIST Project

Scottish Gaelic, spoken by roughly 60,000 people today, is poised for a technological transformation thanks to the ÈIST project, led by the University of Edinburgh. ÈIST [eːʃtʲ] (‘ayshch’) is short for Ecosystem for Interactive Speech Technologies, and means ‘listen’ in Gaelic. The project is funded by the Scottish Government and Bòrd na Gàidhlig, with key partners including the BBC ALBA, NVIDIA, the University of Glasgow and Tobar an Dualchais / Kist o Riches. It aims to support the revitalisation of the language through cutting-edge interactive technologies, including speech recognition.

Since launching in 2023, ÈIST has focussed on developing accurate speech-to-text for Gaelic, but also for English — to cope with code-switching. The initial aim was to produce a system that could generate Gaelic-medium subtitles for BBC ALBA and Radio nan Gàidheal. In a forthcoming paper, the team reports achieving nearly 90% accuracy for chat shows, news and current affairs programmes. Now the team is expanding the technology, making it suitable for more diverse contexts, ranging from Gaelic-speaking classrooms to old fieldwork recordings.

In the autumn of 2025, the creation of an accessible, robust API (Application Programming Interface) will democratise these tools further. Developers and researchers worldwide will gain access to Gaelic speech recognition, embedding the technology into applications ranging from educational software to digital assistants.

Bridging Linguistic Gaps

Currently, Gaelic speech recognition systems struggle to transcribe younger speakers, whose speech patterns often differ from those of heritage speakers. ÈIST addresses this with its dedicated subproject, Recognising Children’s Speech, which will soon gather data from Gaelic Medium Education schools and units across Scotland. This new data will ensure that the speech of young learners is represented accurately.

The implications of this work are profound. Enhanced speech recognition can transform educational tools, such as TextHelp’s Read&Write, providing more effective support for literacy and learning among children. It can also improve accessibility for Gaelic speakers of all ages, especially those with literacy challenges or hearing impairment, providing critical tools for communication and inclusion.

A Community-Powered Initiative

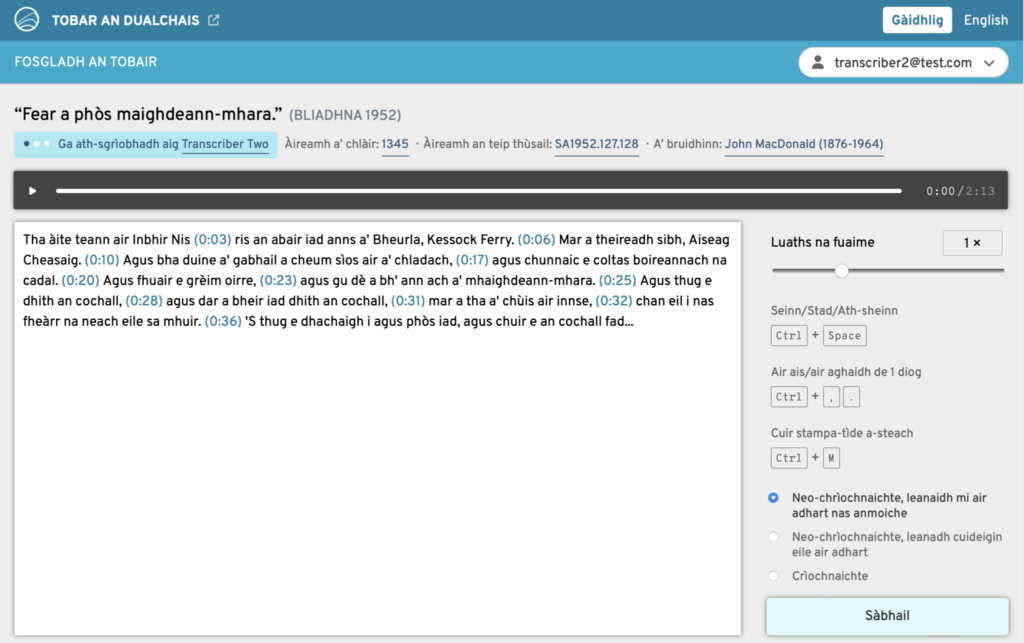

Central to ÈIST’s mission is Opening the Well, a pioneering crowdsourcing platform currently in development and due to launch in the last quarter of 2025. This initiative will mobilise the Gaelic-speaking community worldwide to transcribe audio recordings of traditional narratives and oral history held on the Tobar an Dualchais portal. It takes its cue from Ireland’s successful Meitheal Dúchas crowdsourcing project. These transcriptions won’t just make Scottish heritage more accessible — they will also provide vital training data to enhance the accuracy and versatility of future speech recognition models.

The editing screen in Opening the Well

Risks, Rewards and Responsibility

The team behind ÈIST is keenly aware that speech and language technologies are not neutral tools. Poorly trained models can misrepresent language, distort culture or reinforce social bias. That is why ÈIST places community involvement at the heart of its design process.

The researchers also promote best practices for ethical AI use in revitalisation: curate transparent training data, return outputs to the community (e.g., through DASG, the Digital Archive of Scottish Gaelic), and avoid relying on ‘big tech’ to solve our problems, albeit poorly. It is a values-led approach as much as a technical one.

The Future of Gaelic in the Digital Age

Finally, ÈIST is developing an interactive, text-based interviewer chatbot. This promises not only to engage speakers in naturalistic conversation but also to generate essential data for future applications. When combined with speech technology, such a chatbot could assist with language learning, offering conversational practice previously difficult to achieve outside of a native-speaking community. While this will never replace human teachers, it could be a very useful adjunct to teaching and learning.

In a broader sense, ÈIST represents a powerful case study in how language technology can empower minority languages. The project’s blend of machine learning and cultural preservation illustrates how digital innovation can help to sustain diversity, rather than eroding it. For more information about ÈIST, contact [email protected]

ÈIST Research Team

- Prof William Lamb (PI, University of Edinburgh)

- Dr Bea Alex (Co-I, University of Edinburgh)

- Prof Peter Bell (Co-I, University of Edinburgh)

- Ms Rachel Hosker (Co-I, University of Edinburgh)

- Prof Roibeard Ó Maolalaigh (Co-I, University of Glasgow)

- Dr Alison Diack (Transcriber, DASG, University of Glasgow):

- Mr Cailean Gordon (Lead transcriber, Tobar an Dualchais / Kist o Riches):

- Dr Ondřej Klejch (Speech processing specialist, Informatics, University of Edinburgh)

- Dr Michal Měchura (Web designer and computational linguist)

Links

- Prof Lamb’s inaugural lecture on AI and Scottish Gaelic

- Full demonstration video: Subtitles for BBC ALBA’s ‘An Là’

- A NotebookLM podcast unpicking the results from ÈIST’s new research paper (below)

- arXiv version of Klejch et al. 2025. ‘A Practitioner’s Guide to Building ASR Models for Low-Resource Languages: A Case Study on Scottish Gaelic’.

This article was re-published with kind permission of the author.

This kind of approach is definitely required to bring Scottish Gaelic into the digital age, but I was surprised by the omission of gaming.

Looking for historical precedents, the movable-type printing press technology changed and preserved the English language. What modifications to Gaelic have been observed or predicted by its incorporation into digital technology? You have to consider how Gaelic users are interacting in real life (using predictive text and search terms, inventing new words, debating the language itself online, making humour, creating content and language mods…).

https://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=2722900444

As in the physical world, standardisation, completeness programmes and high-efficiency refactoring bring lasting benefits. DNA has only four bases from which the bewildering variety of Earth life springs. Is there anything in traditional (‘analogue’) Scottish Gaelic that deserves to be selected out for the digital age? Controversy might at least get more people talking.

Could you define what you mean by “traditional” Scottish Gaelic? Tapadh leibh.

Also – “selected out” – could you expand on what you mean by that term, particularly in terms of implications for day-to-day usage?

Mòran taing.

@John Storey, I meant the pre-digital use of the language (‘analogue’ was intended as a strong hint).

I’m not a linguist, but I understand that technological developments like the printing press may have led to (or accelerated) some standardisation of spelling and maybe grammar (so some variants will have been ‘selected out’ and declined from use).

Many languages appear to have vestigial components, some objectionable (French has over-used gender stereotypes, according to some activists), some clunky, some outmoded.

I recently watched an episode of Ottoman Empire by Train with Alice Roberts where a Serbian museum had an exhibition dedicated to two Enlightenment linguists who, it was said, rationalised the alphabet and spelling of their national language.

The English language has a bunch of problems associated with it, but with such a large and varied user-base, these look likely to persist. Scots has its problems too, as dsl.ac.uk illustrates. If Scottish Gaelic has its own problems, maybe some could be addressed now, maybe by such projects, before they become set in silicon? And be healthier, more usable and more attractive in the long term?

(Just to be clear, I don’t view problems here as necessarily a negative, more as an opportunity for solutions; language is a technology, and apt for suitable upgrades and fixes)