The Right to Exist

“My work exists, with or without any award, reward, or prize. I regard the award as an acknowledgement of my work, a verification that it does, after all, exist.” James Kelman, on receiving his Saltire Society Lifetime Achievement Award in 2024.

He said something similar in 1994 in his 1994 Booker-night acceptance speech, after winning the prize for How Late it Was, How Late, “My culture and my language have a right to exist and no one has the authority to dismiss that right.”

The simple statement was brought to mind reading Kenny Farquharson’s piece in which he argued that the Larkhall by-election meant “The death of Scottish exceptionalism”. In correspondence Kenny would write: “The views of the average Scot are not hugely dissimilar to the views of the average English person on most issues.”

At face value, this has some truth.

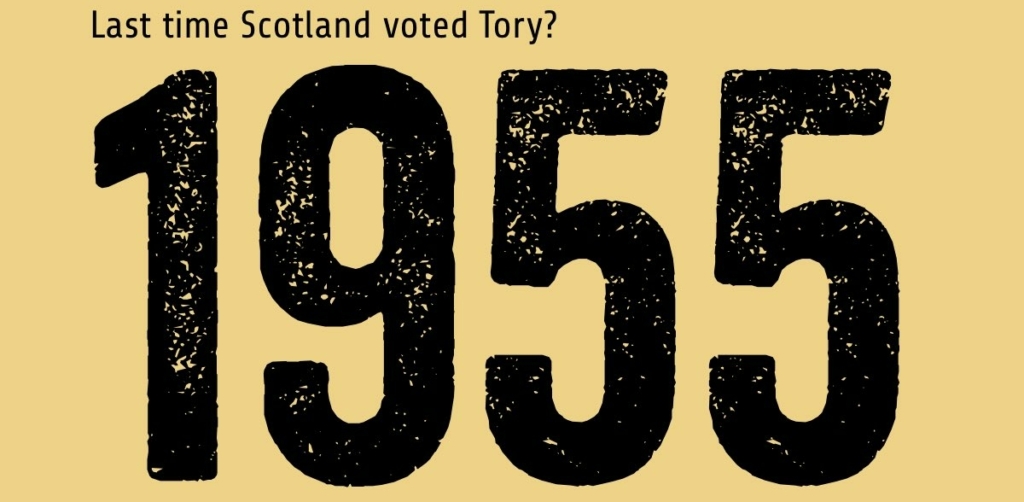

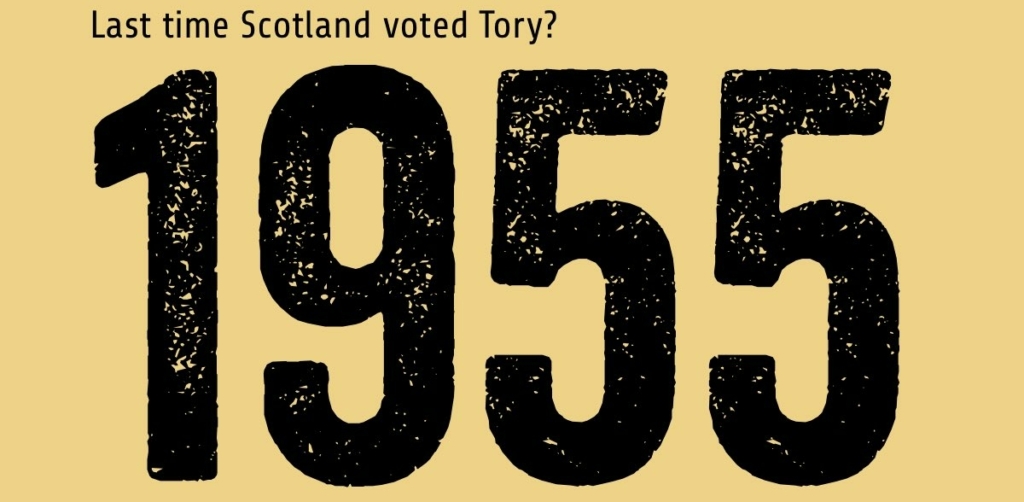

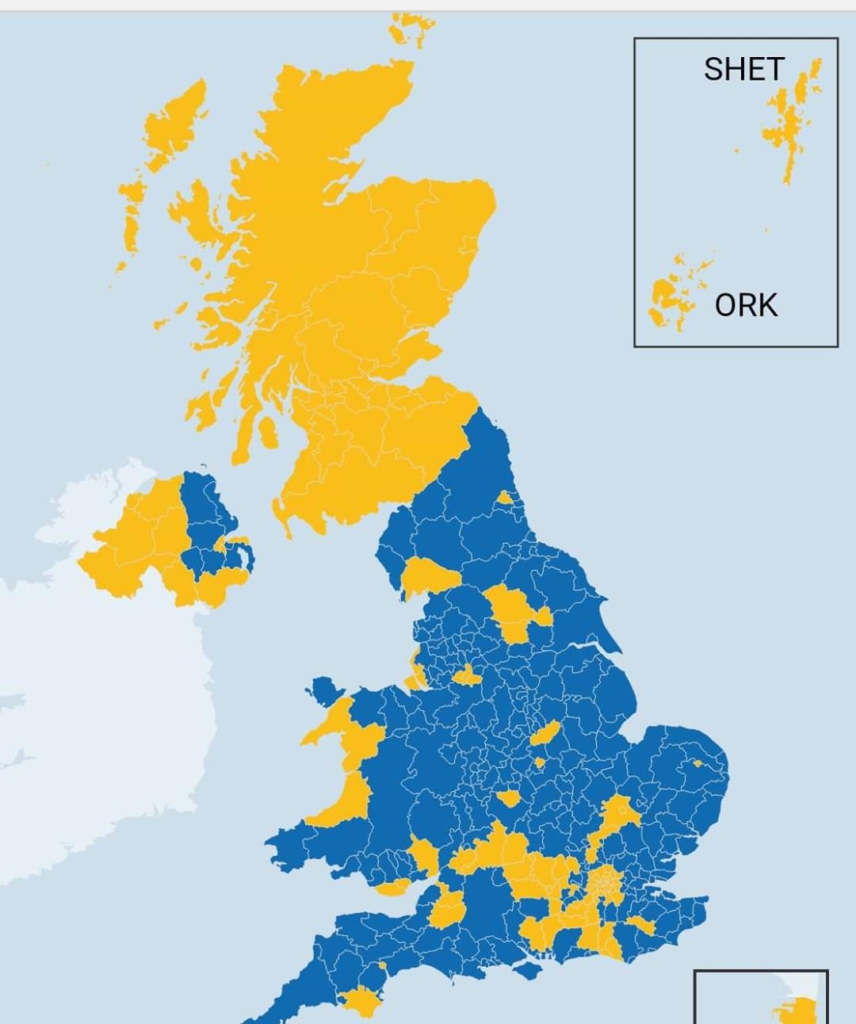

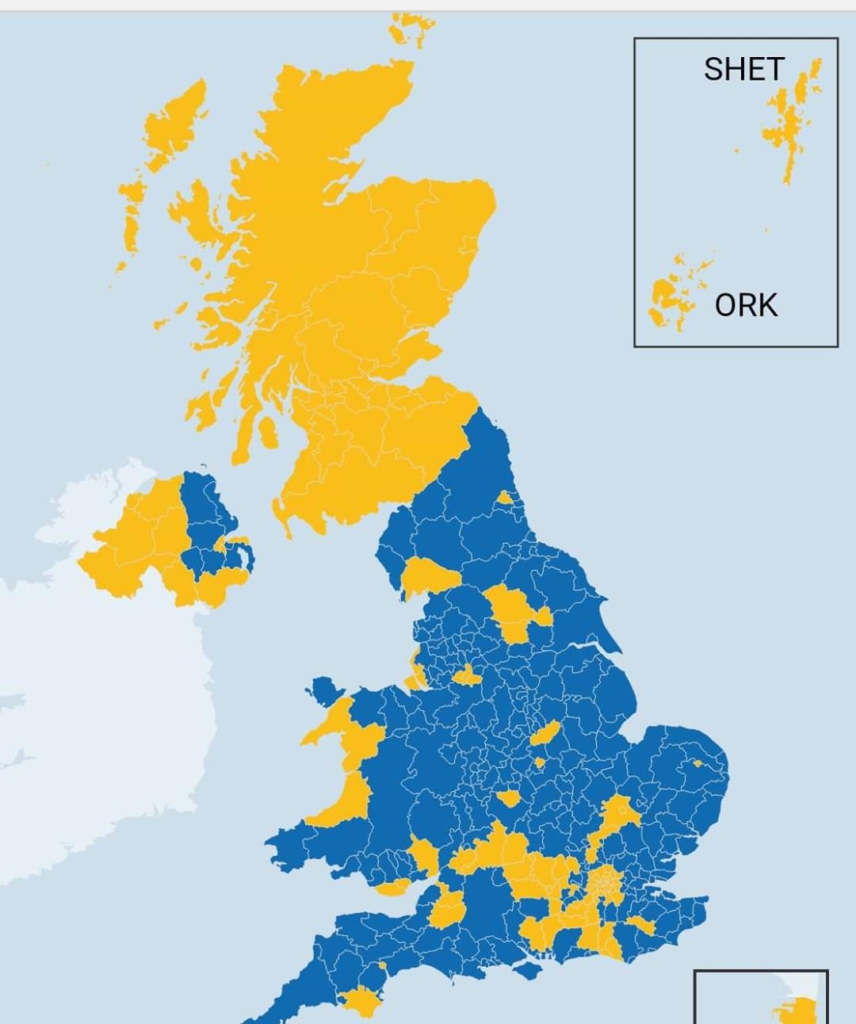

We have our fair share of racists and racism here too. We have a politics dominated by fear, simplism and scapegoating too. We are (clearly) not immune to the forces of what is still being called, euphemistically, ‘populism’. Scotland – even if it has not returned a Conservative government since 1955 – is, in many ways a very conservative country. The differences between ‘the average Scot’ and the ‘average English person’ can be exaggerated, it’s true. We have all been exposed to the same British culture over time.

We live in a homogenised British culture in which the public broadcaster is highly preferential – by dint of just scale and resources – towards English culture and ‘British values’. The media is not devolved for very good reason. People live in the same world of global culture, music and follow the same social media feeds as most of the West. A kid in Inverness is or Granton is likely to support Manchester United or want to go to the Taylor Swift gig. We all live in the same – slightly inane / dead – popular culture.

But Kenny’s argument is that ‘Scottish exceptionalism’ meant a sense of moral superiority and that he himself had not been immune to it in the past, being motivated to support devolution. He writes: “In the 1980s and 1990s I was a fervent supporter of devolution for Scotland and the creation of a parliament in Edinburgh. My enthusiasm had a number of roots: simple patriotism, undeniably; an intellectual belief in self-government and political accountability, certainly. But there was something else too: a strong feeling that Scotland had rejected the Thatcherism that England had embraced, and that a Caledonian communitarianism needed to be acknowledged in greater autonomy within the UK.”

But there is now a more forced assimilation: difference is really threatening and has to be denied. None of this really makes any sense. Why should difference be so threatening? Clearly people in Scotland and England and Wales and Northern Ireland share much in common, some shared history, culture, language and experience of everyday life that has lots of crossover. But they also have distinct national variations, political traditions, different languages religions and laws and experiences that inevitably create different outlooks and mindsets. That shouldn’t be threatening and doesn’t, in my mind, suggest moral (or any other kind of) superiority.

Way back in 2014 I wrote in Scott Hames collection Unstated something to the effect that you could still listen to the Archers in an iScotland, but you’d be able to live in a fully functioning democracy too. Because I think what is behind the Unionist aversion to difference is the need to assert Britishness and to demand assimilation.

Kenny Farquharson has written, and quotes himself from a few months back saying:

“Recent weeks have been hard for the SNP and the broader independence movement. I get that. Not only has the SNP been humbled in the general election, we now have a centre-left UK Labour government backed by a plurality of Scottish voters.”

“With its back against the wall, the SNP has a choice. It can take the route apparently favoured by Stephen Flynn, the SNP leader at Westminster, and seize every opportunity to suggest we Scots are morally superior to the English. Or it can look to a historic new engagement with the other peoples on this island, finding common cause to tackle shared challenges, lending a hand in the rewiring of the British state to give Scotland more of a say.”

There’s a lot to unpack here but just lets begin with the idea that “we now have a centre-left UK Labour government backed by a plurality of Scottish voters.” That notion lasted a few fleeting months and has now completely gone.

I don’t know Stephen Flynn but the characterisation seems absurd. I do however admire the vast optimism that would allow someone to write that we should find “common cause to tackle shared challenges, lending a hand in the rewiring of the British state to give Scotland more of a say.”

In what world does that feel possible, even if it was desirable? Why do we have to rewire the British state and what exactly are the mechanisms to “give Scotland more of a say.” Every experience of the aforementioned British state suggests that it has no interest in any of this.

Take the BritCard .

Does that feel like an invitation to find common cause?

The reality is that Britain and Britishness are not generous ideas capable of expansiveness, they are, increasingly beligerent in tone and singular in identity. Unionism, asserts that to express the desire for self-determination is to be ‘parochial’ and that – even in the face of overwhelming evidence that the ‘Britain’ has changed profoundly, any deviation from cleaving to the current settlement is to be condemned.

There is, at the heart of this debate, a disconnect. Because what is being branded as ‘superiority’ is just the assertion that Scottish culture exists and that we have – for good and bad – a different political culture. And that in making this argument there flows the claim that we can and should run our own country. In other words, the argument isn’t that we are better than anyone else, just that we are as good as anyone else. That’s all. It’s about parity, not superiority.

How Late it Was, How Late

There is no Scottish equivalent of ‘Britannia Unleashed’. There are no anthems which speak of ‘ruling the waves’. There is an imperial swagger to Anglo-British nationalism that has no equivalent in Scotland – just as there is no English equivalent of the Scottish Cringe. Just as there could be no Scottish equivalent of dismissing James Kelman’s culture and writing in the manner it was.

Returning to Kelman’s 1994 Booker speech, with no apologies for quoting at length:

“A couple of weeks ago a feature writer for a Quality Newspaper suggested that the term “culture” was inappropriate to my work, that the characters peopling my pages were “pre-culture” — or was it “primeval”? I can’t quite recall. This was explicit, generally it isn’t. But — as Tom Leonard pointed out more than 20 years ago — the gist of the argument amounts to the following, that vernaculars, patois, slangs, dialects, gutter-languages etc. etc. might well have a place in the realms of comedy (and the frequent references to Billy Connolly or Rab C. Nesbitt substantiate this) but they are inferior linguistic forms and have no place in literature. And a priori any writer who engages in the use of such so-called language is not really engaged in literature at all. It’s common to find well-meaning critics suffering from the same burden, while they strive to be kind they still cannot bring themselves to operate within a literary perspective; not only do they approach the work as though it were an oral text, they somehow assume it to be a literal transcription of recorded speech.”

“This sort of prejudice, in one guise or another, has been around for a very long time and for the sake of clarity we are better employing the contemporary label, which is racism. A fine line can exist between elitism and racism and on matters concerning language the distinction can sometimes cease to exist altogether.”

… There is a literary tradition to which I hope my own work belongs, I see it as part of a much wider process — or movement — toward decolonization and self-determination: it is a tradition that assumes two things: 1) The validity of indigenous culture; and 2) The right to defend in the face of attack. It is a tradition premised on a rejection of the cultural values of imperial or colonial authority, offering a defence against cultural assimilation, in particular imposed assimilation.

Unfortunately, when people assert their right to cultural or linguistic freedom they are accused of being ungracious, parochial, insular, xenophobic, racist etc.

“As I see it, it’s an argument based solely on behalf of validity, that my culture and my language have the right to exist, and no one has the authority to dismiss that right, they may have power to dismiss that right, but the authority lies in the power and I demand the right to resist it.”

The Disconnect

The problem, as I have said, is the disconnect. Farquharson’s argument lands in a world in which languages, and indeed whole cultures have been (almost) eliminated. Not by mistake, but by edict. So it’s important to point out that not only that cultural and political differences do exist, but they only exist because they have been defended against erasure. And, that the deliberate erosure of whole cultures was part of the project to build Britain.

If you write about – or in – Scots and Gaelic on a public platform – you are sure to be exposed to a volley of abuse. This is well documented. There is no such equivalent for English language speakers. It’s in this context that the ‘everywhere’s the same’ argument seems so disingenuous.

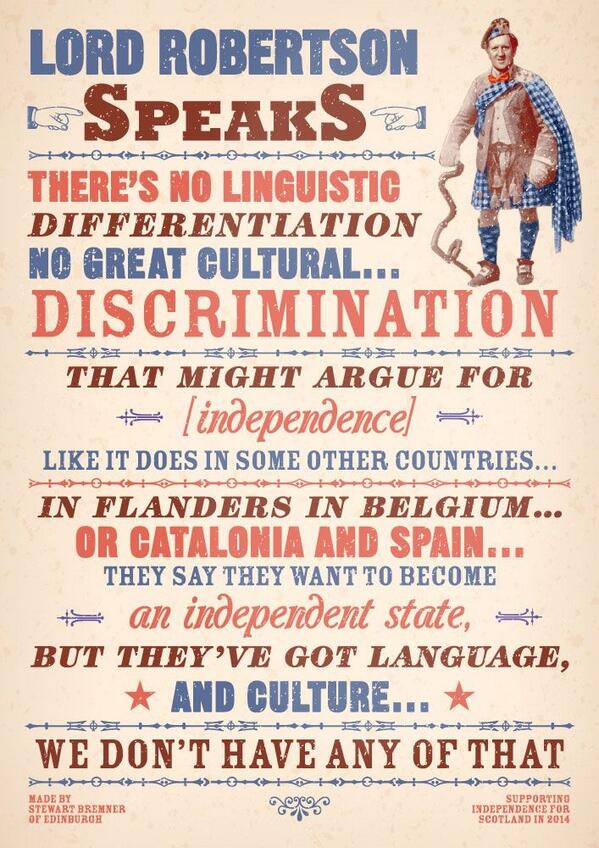

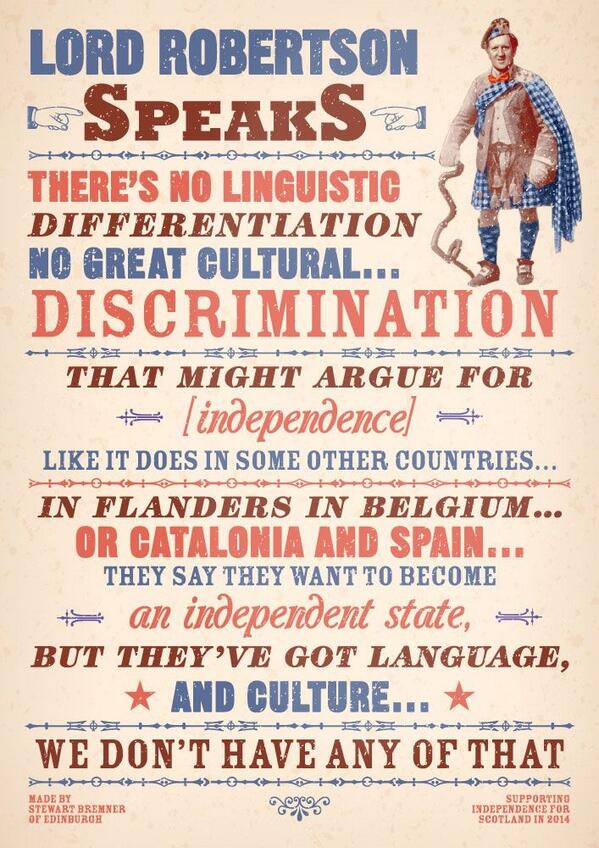

Examples of cultural self-loathing are everywhere. This is not necessarily deliberately cultivated, it is very often just assumed. At times it is not that a hatred of Scottish culture is the problem, but rather the assumption that no such thing exists. George Robertson famously stated in a public meeting in 2014 that Scotland doesn’t really have language or culture at all …

So, can you have different political cultures without moral superiority? Of course you can. Larkhall is a wake-up call to Scottish indifference or complacency about the rise of the far-right. Some communities in Scotland have, for the last few years, been in an interesting conversation about our past, our role in slavery and empire and a reckoning with our shared complicity.

But if your politics is such that you need to suppress difference in order to impose the orthodoxy of Britishness you are in a losing battle and have to make sense of both our history and our present relations.

Yes, we will still be able to listen to The Archers in an independent Scotland.

But a bigger issue is that there’s no Scottish equivalent of The Archers.

Now that River City is being axed, maybe the BBC could create a Scottish radio soap?

Googling suggests that there hasn’t been one since Kilbreck in the early 1980s.

Another thoughtful piece. I’ve no idea how Irish msm have evolved in the last 100 years- they’re by far our nearest,most obvious exemplar, yet the only trends I’ve noticed in my lifetime are the drift to London of presenters deemed talented and the job of Political editor for the Beeb invariably has to go to a Unionist- I only go back to WD (Billy) Flackes!

I have an anecdote from the 1980’s relating to when The Proclaimers first came to public attention. A woman at my work mocked them saying imagine singing like that. I pointed out to her that they were singing exactly as she spoke every day. She then replied, and I kid you not, saying ‘aye but yu cannae sell records speakin like that.’

I did point out the Beatles sung in their local dialect and they hadn’t done too badly.

Trivial as this anecdote sounds it did rather neatly sum up the cultural cringe many in Scotland had at that time.

Much to be praised in this nuanced, thoughtful article and I agree with it for the most part.

I would question whether any culture has a ‘right’ to exist though. It has the right to defend itself, demand recognition, even protection against hegemonic onslaught and more power to the elbows of those engaged in that but a right to existence? I would say a culture does in the relative sense that it has a right not to be quashed by a more dominant culture (which in turn might do the same against an even bigger one, e.g. British culture versus US culture), but in an absolute sense? In the broad sweep of history many cultures have bitten the dust, some very powerful at the time, many much smaller, so are we saying they had all had a right to exist and should never have been superseded, replaced, or just died?