Notes on a Scottish Republic of Letters

The health and vibrancy of the Scottish cultural landscape was once acclaimed across public life. Not so long ago many folk felt that we had been living through a renaissance of expression and talent, not unlike such periods as the 1930s, and that this had lasting import on how we viewed ourselves and on our political disposition.

Today things are a lot less rosy and sure-footed. Instead of the above, there is now a discernible mood of angst, worry and negativity – centred particularly on funding, controversies around corporate sponsorship, sustainability, and how the cultural sector deals with divisive debate. There is also the realisation that a quarter century of devolution, and nearly two decades of the SNP in office, have brought no clear championing of the arts or recognition of its place at the heart of the nation.

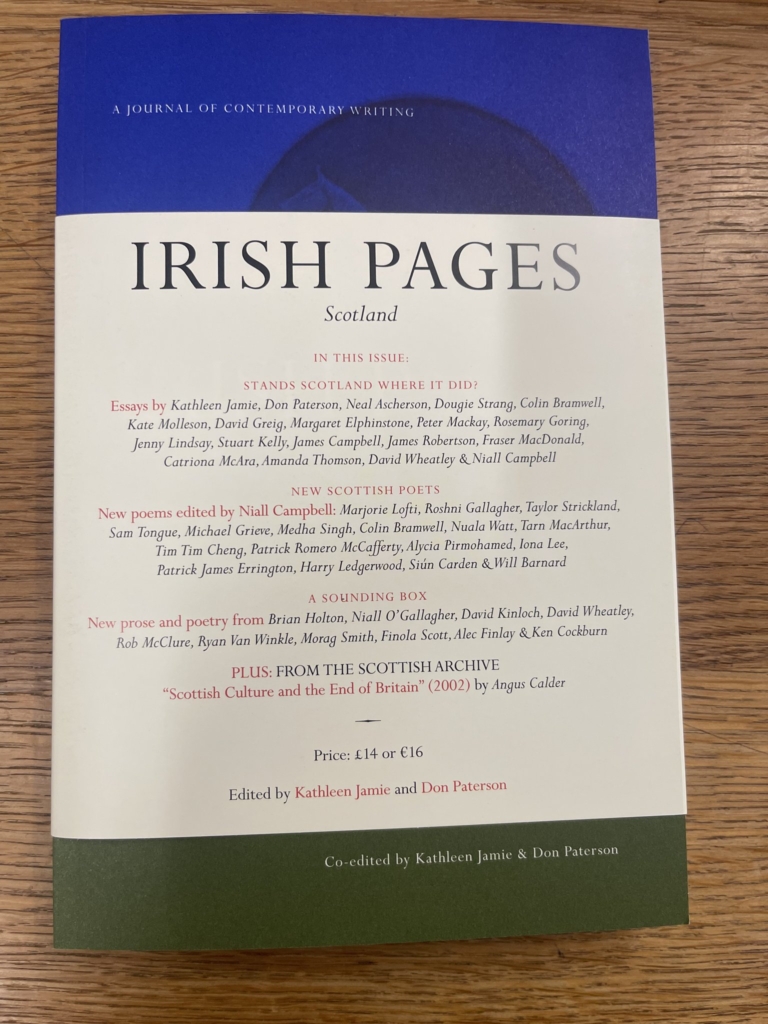

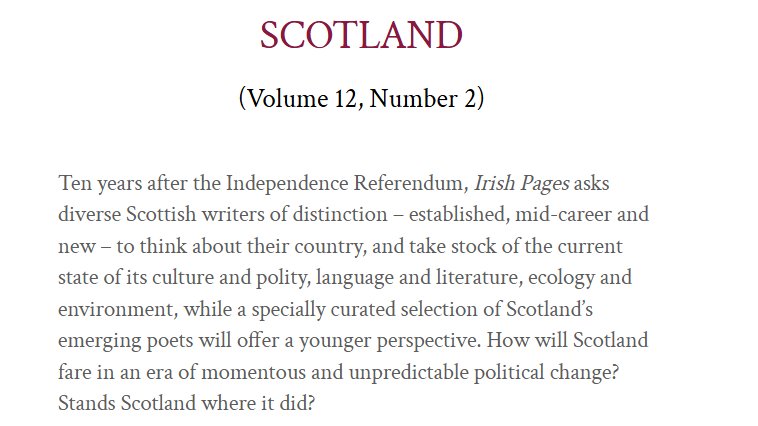

Into this environment comes Irish Pages, the respected cultural journal, with a special issue on Scotland co-edited by Kathleen Jamie and Don Paterson and funded by Creative Scotland. The first section, that this piece focuses on, is entitled ‘Stands Scotland Where It Did?’ – citing again the Shakespeare quote given modern sustenance in the Thatcher age by Willie McIlvanney. It contains essays by the likes of Neal Ascherson, David Greig, Margaret Elphinstone, Rosemary Goring, Stuart Kelly, Jenny Lindsay, Fraser MacDonald, Amanda Thomson and the co-editors.

The foreword by Jamie and Paterson lays out their invitation to writers. It is ten years from the indyref when they began this process; the loss of hope, spirit and possibility that was the independence movement then; the broken promises of the British state; more than that the broken nature of the British state.

Jamie and Paterson state that their contributors have a ‘defence of the independence of the artistic mind’ and have ‘made some small contribution to the cultural autonomy Scotland now enjoys.’ They then state that the main thrust of this collection is a gathering of ‘elders [who] have been sidelined’ because, they claim, ‘most of us don’t do social media, the medium through which so much cultural business is now conducted.’

They continue that ‘It has left us, at least in the eyes of the young, looking irrelevant and out of touch in a way our own elders did not look to us’ making references to ‘the culture wars’ and the missed opportunity in it for ‘inter-generational exchange’. This could be a fair point but is sadly one this collection leaves unaddressed.

An Elegy for a Lost Scotland?

This collection brings together various ruminations of quality, containing some valued observations. It is beyond space to summarise all of them, suffice to say that Neal Ascherson’s has his usual vitality, Jenny Lindsay makes acute observations from the frontline of the ‘culture wars’, and the likes of Stuart Kelly and James Robertson provide some arch and well-put perspectives.

Throughout the collection blows a distinct air of loss, and of looking back nostalgically to better times in yearning for a past Scotland. There is an explicit disillusion with present-day Scotland and a prevailing tone that we have lost our way in how we value and see culture. Underlying this is the implicit sense that things culturally were better during the Thatcherite era when we knew what we stood for and what we were against, whereas now we do not and the landscape is disfigured by division.

Rosemary Goring’s essay explores the decline of Scottish book reviewing and of literary journalism. This piece has noteworthy points, the writer having been literary editor of The Herald, Sunday Herald and The National – at one point at the same time. She writes about Scottish newspapers at their peak as ‘bulwarks of culture’ without defining whose culture this was and whose it wasn’t; the implicit assumption being that she is talking about a bourgeois, middle-class culture which claims to speak for the nation or a large part of it.

She notes the decline in importance and space of book reviews, and what she sees as the negative take-over of book festivals by celebrities. Various Scottish specialist journals have fallen by the wayside leaving a gap in platforms for writing. A significant amount of space is given to a defence of the Scottish Review of Books edited for over a decade by her partner Alan Taylor (which she references).

[see Patchy and Negligible – by Claire Squires]

Nowhere are any of its shortcomings talked about in the cultural world at the time. Its lack of diversity, its gathering of male writers of a certain age, and its incestuousness, one leading cultural figure commenting at the time that it was ‘the equivalent of an aging male pub crawl.’ SRB was a missed opportunity and no critique is offered. Just as revealing not one mention is given to the iconoclastic Variant edited by Leigh French over a similar amount of time and funded by Creative Scotland. It developed a critical independence of mind, community of practice, and gave platforms to a host of new and radical voices which left an impressive legacy and is sorely missed (even by some of those it targeted). Variant’s example and fearlessness is relevant today and to current cultural considerations.

Goring’s essay has a revealing honesty about the changing nature of literary Scotland and the prevailing retreat and attrition that many feel. Missing from this and the entire collection is any analysis of the changing contours of Scotland’s public sphere: the wider environment in which ideas, culture, media and others are disseminated and sometimes silenced and excluded.

There is no substantive reflection on the changing nature of this in Scotland, the UK and globally, which is dramatically altering public discourse and conversations here and across the world in ways we are only beginning to understand. The old hierarchies and reference points are crumbling, the BBC included, and in their place, a much more disputatious public sphere is emerging where none of us yet know the rules – or indeed if there will be any. Some reflection on this would have added weight to this collection.

Talking about the State of Scotland

This brings us to the Don Paterson essay reviewing what has happened to Scotland post-2014 that covers much ground. Suffice to say that Paterson does not like the present-day state of Scotland – culturally and politically. He offers a set of villains whom he holds responsible for the retreat, retrenchment and general malaise of political and public life that he feels has happened. This includes the SNP under Sturgeon, Scottish Greens and what he calls ‘identitarianism’ which ‘generates tribal division’ and ‘divide and rule’.

There are numerous illuminating swipes from Paterson. The Scottish Greens we learn are ‘a tiny pro-independence minority party’ with ‘eccentric and ill-conceived policy obsessions’. In fact, they are a force which won 8% of the regional list vote in 2021 and set to win more in 2026 which isn’t carte blanche a defence of everything they do.

Paterson makes the legitimate point of the missed opportunities post-2014 for the SNP and independence. But the road he outlines is of an abrasive, assertive nationalism declaring after 2015 a unilateral declaration of independence, looking to a UN route, and the SNP withdrawing from Westminster. These are not approaches that anyone serious was suggesting in the aftermath of the 2015 tartan tsunami.

Another strand sees Paterson defend Baillie Gifford’s sponsorship of Edinburgh International Book Festival calling them ‘one of the most ecologically responsible investors and major patrons of the arts’ – the latter unquestionably true until recent controversies; the former deeply questionable.

One area of public life he thinks has gone wayward is the rise of ‘diversity’ that he asserts has introduced a London-centric mindset and ‘a narrow, entirely ideological definition of ‘diverse’ – derived from recent US political history’ and ‘a holy reservoir of liberal wisdom – and from America.’ There is truth in the observation that ‘our own gatekeepers continue to take their cultural lead from London’, but this does not need to be framed in an almost Trumpian take on ‘DEI initiatives’ and ‘the woke’. There has been a London framing of many devolution policies and actions. The very idea of Creative Scotland and ‘the creative class’ came out of the New Labour era and was adopted by a Scottish political class just as it was going out of favour in Whitehall. None of this gets a mention.

The huge pressures on higher education in Scotland are reduced to a few choice examples. One is the idea that free tuition fees with its over-reliance on international students for income has resulted in ‘discrimination against the middle class and working-class Scots sometimes finding themselves the only Scots in their entire student cohort.’ The system has produced many unintended consequences, but this is a strange way of putting it considering the advantages of the middle classes, the rise of English privately educated students in Edinburgh and St. Andrews, and the stigmatisation of Scots working-class students at Edinburgh increasingly coming to public attention.

Barely mentioned is the wider canvas of what has gone wrong with the SNP and independence, beyond a signing-off list at the end of the article listing ‘cowardice, personality cult, unwise alliances, middle-management overreach … Holyrood bubbles and Westminster troughers.’ This seems an afterthought, and left unsaid is the cumulative effect of incumbency on the SNP, the collapse of SNP governance, the corrosive centralisation across public life, and perhaps critically, the thin nature of what passes for social democracy in Scotland and the narrow intellectual and self-reverential values of too much Scottish cultural and political nationalism.

Beyond the Cringe?

We have spent decades telling ourselves that we are all ‘Jock Tamson’s Bairns’, that we are more egalitarian and progressive than England, that we are comfortable within our identities, and that our nationalism is not like other nationalisms, but inclusive and cuddly. It does not matter that all nationalisms tell themselves such comforting stories. Or that the impasse in which we currently find ourselves shows the exhausted, threadbare nature of the stories we have repeated in recent decades.

This collection is filled with gifted writers who have enriched cultural life in Scotland and further afield. Yet it is also a self-declared group of elders articulating a particular generational story of prominence and impact that regards the Scotland of the 1980s and Thatcherism as a watershed – and the cultural response to that of importance then and with lessons for the present. There is an unstated sense that this generational story is slowly and inevitably as it must passing into the realms of history to take its place in the pantheon of other past stories. And like many storytellers they are having trouble adjusting to that and to the show moving on.

No publication can cover all the issues facing Scotland. But there does seem to be some selection of priorities and omissions which could raise an eyebrow. Hence, the fertile period of Scottish culture of recent decades is just assumed rather than investigated. Hence, the current state is blamed on a host of expedient and short-term factors which could be addressed. Nowhere is there an awareness that maybe the ‘renaissance’ thesis about the 1980s was overdone and that Scotland, policymakers and cultural movers have failed when they could have built a lasting ecology of cultural platforms and resources. It is not easy, but other small nations do. And this isn’t just about independence, as the SNP’s two decades has seen the narrowing of cultural policy and horizons.

A particular area missing is any investigation of the consequences of the SNP’s cultural choices and which Scotland they have prioritised. For all the discontent in these pages these figures represent the broad insider cultural class that the SNP and Scottish Government have tried to keep on board. It is noteworthy that there is no real criticism of the policy and funding actions of Angus Robertson, part-time Culture Secretary, and the belief of many in the arts and culture world that he has shown preference to middle-class, well-connected Edinburgh cultural bodies at the expense of the rest of Scotland. The evidence points this way – £300k to bail out Edinburgh International Book Festival post-Baillie Gifford, yet Glasgow’s much loved and more working-class Aye Write was left to struggle and cancel last year’s festival; and the Scotland beyond the Central Belt barely getting a look in.

Culture and politics are never easy bedfellows despite repeated deterministic narratives in Scotland and elsewhere. David Greig points out that the indyref ‘appears to have produced no significant art’ from ‘any novels, poems, plays or films that make a serious attempt to reflect that extraordinary moment.’ It is a salient point (leaving aside all the independent and DIY productions). But sometimes existential political questions are just too big to comprehend, we are still living in the indyref’s slipstream, and the kaleidoscope altered by ‘the Big Bang’ of 2014 has yet to settle. Then again, this cultural-political disconnect should make anyone pause about simplistic interpretations.

The Irish Pages collection captures a moment in time: a generational account of a certain group of cultural voices who feel anxious, angry, annoyed and disappointed –of whom several spill over into a conservative curmudgeonly reactionaryism. Much of the overall mood is understandable, but there is in many places pettiness, a parochial attitude and no practical suggestions for tackling the malaise. Corporate capitalism, zombie neoliberalism, and the threat of right-wing populism, demagoguery and disinformation all go unexamined, reinforcing an overall feeling of powerlessness.

Many of the big challenges facing arts and culture get only the most passing reference – the challenge to artists and creatives in an age of hyper-capitalism, inequality and grotesque power; the instrumentalisation of art and culture by government policy one example of which was the creation of Creative Scotland; the toffification of culture and closure of opportunities to working-class people; and the need for Scottish cultural institutions to nurture new voices, talent and people. There is a conspicuous absence in this collection of trying to make sense of culture and the modern world through critical thinkers and intellectuals, as if we can just make sense of things through a benign liberalism.

We need to wake up and recognise that things are not healthy in the cultural landscape of Scotland. The stories, memories and reference points that contribute to making us a living community and nation have as one of the central pillars culture. We cannot let it wither, be celebrity-driven or reduced to the onward march of globalising platforms.

A vibrant, diverse cultural environment requires radical change. It needs dramatic action from the Scottish Government, SNP and ideas of independence, as well as from other political parties and agencies. It necessitates the arts and cultural sector thinking differently about its role and seeking alliances to challenge current broken models. And it needs serious thought about how we can create new platforms and publications to give writers, artists and creatives spaces and profile to learn, evolve and prosper, alongside a culture with a place for disrupters, innovators, rebels and outsiders. Maybe in our supposed all-encompassing passion for ‘diversity’ according to Don Paterson we should reach out and embrace the idea of a multitude of different Scotlands.

It did leave me wishing for a clarion call from the likes of the late Angus Calder who wrote so eloquently about the need for a ‘Scottish republic of the mind’. But on the other hand we already have older guides to give us sustenance, and it is that new voices, directions and ideas we need which sadly this edition of Irish Pages is desperately short of.

I agree with the author on much of this.

I’d like to request clarity on the meaning of phrases like

“arts and culture sector”

What does that mean?

How is it defined?

What does it include?

The labels ‘Culture’ and ‘The Arts’ seem these days to be used almost synonymously, when it fits some narratives and as distinct when it suits others.

I prefer to think of culture as – how we live our lives.

The arts are important to that but surely are only one facet of it.

Some thoughts on the state of a few areas of Scottish culture.

Our music is certainly in good health.

Our bagpipes are possibly the world’s most famous folk instrument, though this is largely because of the military tradition of pipe bands.

A Scotsman invented TV – in 1926, John Logie Baird made what’s widely regarded as the world’s first true public television demonstration.

The next year, another Scotsman, John ‘Lord’ Reith, became the first director-general of the BBC.

But Scotland has since punched (or been punched) well below its weight in producing TV.

There are many types of TV programme which Scotland doesn’t make at all, hardly makes, or has never made:

– Scottish children’s news (no Scottish Newsround).

If you google “Scottish children’s news”, you get 1 result – https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/schedules/service_rt_regional_scottish/1934-03-29 – from 1934!

(Does that make this phrase a Googlewhack?)

– Scottish game shows / Scottish quiz shows

– Scottish talent shows (no Scotland’s Got Talent)

– Scottish chat shows

– Scottish teenage drama / drama for older children

– Scottish animation / cartoons

Though there have been LOTS of murders.

You could almost say that Scottish TV has been ‘murdered’.

Our crime writers (murder again!) are commercially successful. But not so our children’s writers.

I’ve been asking friends and family recently if they can name any living Scottish children’s authors, apart from JK Rowling.

Few have been able to.

Our second must famous children’s author is probably Chris Hoy, but he’s not famous for his writing.

Alexander McCall Smith has written some children’s books, but beyond these famous names, I think most of us would struggle. There are talented children’s authors in Scotland, but few others with much commercial success.

On diversity, it’s worth noting that there are now more Asians than Scots in the UK

(or at least, than the population of Scotland):

https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/ethnicity/bulletins/ethnicgroupenglandandwales/census2021

‘”Asian, Asian British or Asian Welsh” accounting for 9.3% (5.5 million) of the overall population’ (in England & Wales alone)

https://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/2022-reports/scotlands-census-2022-rounded-population-estimates/

‘On Census Day, 20 March 2022, the population of Scotland was estimated to be 5,436,600’