Freedom of religion and freedom from religion in today’s Scotland

The Scottish Parliament is currently running a public consultation on religious observance in schools. At first, I was excited by the prospect of the Scottish education system finally, in 2025, respecting a young person’s right not to participate in hymns, prayers, and Christian worship if they choose not to. However, it seems our government is still, at least to some extent, reluctant to challenge the religious powers that be.

The consultation does not seek to gauge support for respecting a child’s right not to participate; instead, it proposes allowing children to have a ‘view’ on the matter (whatever that may mean). By religious observance, we are referring to attending church services or church-led assemblies where children are read the Bible and required to sing hymns and join in prayers. This remains a regular end-of-term feature even in Scotland’s non-denominational schools. The term ‘non-denominational,’ is often a source of confusion, it does not mean secular; it simply means that the school is not affiliated with a specific Christian denomination.

The consultation also addresses parents’ rights to withdraw their children from religious observance (which is strange as this is a right that has existed for some time) and religious education (which is distinct from religious observance).

As a teacher in Scotland, I am well-versed in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). We regularly teach children about their human rights, and public bodies in Scotland are legally obliged to report on their progress in upholding and implementing these rights.

Three articles of the UNCRC are particularly pertinent here:

- Article 12: “Every child has the right to express their views, feelings, and wishes in all matters affecting them, and to have their views considered and taken seriously. This right applies at all times.”

- Article 13: “Every child must be free to express their thoughts and opinions and to access all kinds of information, as long as it is within the law.”

- Article 14: “Every child has the right to think and believe what they choose and also to practise their religion, as long as they are not stopping other people from enjoying their rights. Governments must respect the rights and responsibilities of parents to guide their child as they grow up.”

I see no way in which these rights can be reconciled with the failure to allow young people to opt out of religious observance. The principle that “every child has the right to think and believe what they choose” is especially relevant. Why would a country like Scotland, which aspires to lead on children’s rights, fail to take these particular rights seriously?

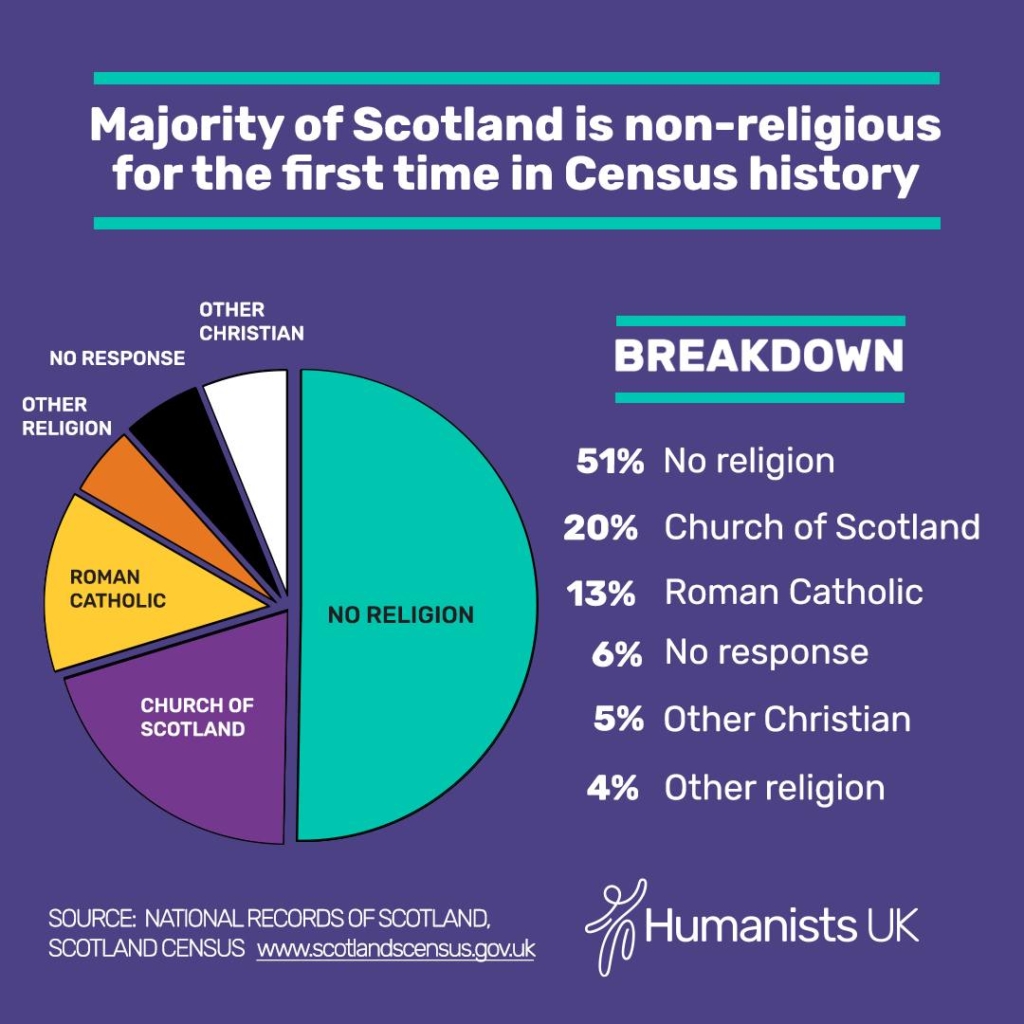

Despite census results showing Scotland to be a majority secular nation for the first time, it appears that fears of upsetting powerful Christian institutions persist. The religious lobby in Scotland remains influential. For example, the Bishops’ Conference Scotland recently lobbied Parliament to complain that anti-abortion groups were not represented on the Scottish Government’s Abortion Law Review Expert Working Group. The Society for the Protection of Unborn Children (SPUC), another anti-abortion organisation, also appears frequently in lobbying records. What makes SPUC’s influence especially noteworthy is its considerable access to schools in Scotland.

When parents do withdraw their children from religious observance, it is often the case that no meaningful alternative is provided, leaving children feeling ostracised from their peers. Some would argue that Scotland is a Christian country, but the census results clearly suggest otherwise. Imagine if children were given a genuine choice—attending church or participating in an alternative activity that allowed them to explore their beliefs and values with their peers, rather than simply being supervised while opting out of the main activity – as if often the case.

Religious observance can sometimes cause distress to children. Over the years, I have taught pupils who found concepts raised during religious observance deeply upsetting. Some have asked heart-breaking questions such as, “Why did God let my parent die?” and “Why do I have to pray to that God?” Furthermore, I question how notions such as heaven, Satan, and eternal damnation align with the trauma-informed approaches that the Scottish education system purports to embrace.

Another conversation that Scotland seems unprepared for is religious observance in schools as a workers’ rights issue. As a teacher, why do I not have the right to refuse participation in the worship of a deity I do not believe exists or to decline practices that contradict my deeply held beliefs? Despite my efforts to work only in non-denominational schools, employers can assign teachers to Catholic schools, where my own beliefs may present professional challenges. As a student teacher, I witnessed non-Christian colleagues being sent to denominational schools. Many returned feeling unwelcome and fearing their careers were over before they had even begun. While this is not the experience of all non-denominational teachers on denominational placements, it occurred frequently enough among those I knew to raise serious concerns.

The government consultation also covers religious education. Unlike religious observance, I do not believe religious education should be optional—no more than maths or literacy. Religious education can be an invaluable part of the curriculum, helping pupils understand those who are different from them. Teaching about Judaism and Islam, in particular, is vital in combating antisemitism and Islamophobia, and the conspiracies and disinformation about minority groups which fuel hatred. However, review of the curriculum is arguably still needed. One-third of the non-denominational RE curriculum is dedicated to Christianity. In 2025, it feels outdated to categorise all other religions as ‘world religions,’ as though they are somehow less integral to Scottish society.

This conversation is long overdue. I hope a diverse range of views are collected and considered—not just those of religious lobbying groups seeking to maintain the status quo.

More broadly, something even greater is at stake. Scotland is an increasingly secular country, emerging from a long history of religious institutions wielding significant power. Among the freedoms we now enjoy, it is both freedom of religion and freedom from religion that underpin these liberties. The right of every young person to develop their own beliefs is surely a fundamental right in a modern Scotland.

Being exposed to religious practice did confirm me as an athiest by the age of ten. Unfortunately I only discovered Christopher Hitchens after his passing, but he and Richard Dawkins carry the torch as it were, for me anyway.

All children are born atheists and only become whatever their parents and/or school/tribal religion is through interdicts and conditions of worth, in effect a form of child abuse.

Thus whilst it is fine if someone wants to have a religion as an individual, and they must have the right to choose it or not, it is a grevious harm to society to use religion as a basis for national policy, and that includes in education. By all means teach children about all the religions, and none-religion, and let them choose one if they feel the need. But do not inflict their ceremonies and awful assumptions on them, at any level of governance. The bible should be filed under fiction, and studied in English Literature lessons.

It is actually quite easy to prove there are no gods.

1) toothache, or cancer, no one could be that evil to invent such things, or, if he/it did, why are you worshipping such a horror anyway? Why would a god invent a splitable atom thus allowing one of his creatures to develop nuclear weapons?

2) more importantly, view the planet through an ecological lens and it becomes apparent that gods are man-made constructs.

How many penguins do you see doing the Hajj to Mecca?

How many giraffes do you see building shrines in the treetops of the savannah?

How many dolphins do you see gathering round a stone and praying?

and so on

Never, of course.

Religious behaviour is not apparent amongst the 8.7 million or more other species on the planet, it is safe to say it is purely a behavioural pattern of homo sapiens. If it doesn’t appear in nature, then it isn’t natural, ie doesn’t exist.

And we have, through hierarchical structure of kings, governments, tyrants and religion, become separate from nature ever since we adopted agriculture – in our arrogance as a species assumed nature is something to tame, use up, commodify and destroy at will. Religion is and always was part of that narrative, a narrative of control, that we tell ourselves it is okay to shred the planet in an attempt to continue our civilisation. This will not end well.

Strangely enough, religions have been fairly mute when it comes to climate chaos. Overshoot does not enter the religious lexicon, and now religions appear unable to provide any ‘answers’ to the predicaments we are in. The rise of secularism shown in the graphic in the article is interesting, perhaps people are beginning to realise that the power of nature far exceeds that of any mythical gods.

@Mark Bevis, I read Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion, and was disappointed by its lack of rigour and its incoherence. I was pretty well up on the philosophical arguments for God and how even my university chaplain and philosophy of religion lecturer had to give up on them: there’s no good reason to believe, hence the requirement for faith. Judging by Dawkins’ later pronouncements, I wouldn’t class him as a defender of schoolchildren against abuse. He seems cut from the same kind of cloth as his established religion opponents. I might agree with many of his espoused views, but am not impressed by the quality of his expressed reasoning. In this and maybe all things, better not to have any heroes.

I think my dog believes that I am God, The Bounteous Provider.

Surely most important of all is tolerance and respect, and to encourage compassion and mutuality, rather than insisting that those who do not share your own way of thinking are wrong.

I agree, broadly, with the thrust of this article.

In my experience of more than 39 years’ experience teaching in Scottish schools, including in one denominational school, what she writes has been discussed informally in staff rooms since I first entered one, as a teacher, 55 years ago. Probably, it has been discussed in staff rooms since the Act of 1873 which made education compulsory, which, for almost all children meant attending school.

Until then, education for the wider populace, when it was provided, was by Christian organisations, and, after the Act, in order to fulfil its requirements such organisations were co-opted to provide the service. In addition, the Kirk was given a legal position on the governing bodies and it had influence on the framing of the legislation which gave religious observance its compulsory place in the curriculum. The 1918 Education Act extended these positions to the Roman Catholic Church, too.

The number of Jewish children in Scotland in those days was relatively small and local ad hoc arrangements were made. Only from the late 1950s we’re there children from Hindu, Muslim and Sikh backgrounds attending schools in significant, though, very low proportions. In a great majority schools in Scotland, the number children from ‘non Christian’ backgrounds is almost vanishingly low. There a few schools in areas of Glasgow, for example, where the number of children from practising religious (other than Christian) backgrounds is high and these schools have made commendable efforts in providing for religious observance for those children and have also incorporated these religions into a much broader religious education curriculum. Often, the observance provision was permission for the children to be absent from school to attend the local Synagogue, Mosque, Temple, Gurdwara. These are pragmatic responses, are largely welcomed by the parents of the faith groups and are accompanied by good will on all sides.

Historically, for most white Scots it was presumed that they were Christian, either Protestant or RC, even if their families were not church attenders. For those attending non denominational schools, religious observance was something that was part of school experience and they just went along with it. They could opt out, but most did not, mainly because the time allocated was so small that it was not worth bothering about.

For those attending denominational schools, however, by choosing to attend, since there were non denominational schools available to them, the presumption that the children were religious believers was stronger and the school ethos exerted pressure to attend, especially as those in senior positions had to have their faith attested in order to be eligible to hold these positions.

In the non denominational sector, the requirement is only for a minimum of three communal observances per year. Usually, these are at Christmas, Easter and one other occasion, which is often part of an end of year assembly. While observed, Christmas and Easter have, in our society, lost much of their religious meaning for many and, nudged a fair bit by commercial interests, are still periods for communal enjoyment and celebration, with, increasingly, no religious aspect.

Largely, the school observance is in that context, too and is part of a wider package of dance/disco, visit to a panto, wnding-down-after a-busy-term.

So, largely, by use and wont, religious observance in the non denominational sector has become something other. Maybe it is time to remove the requirement for observance. The removal of representives of the churches from Education Committees in some Council areas is a further example of this gradualist trend.

The issue is, principally, one for the denominational sector, explicitly, the Roman Catholic schools. Given the history of persecution of Roman Catholics in Scotland since the Reformation, though, happily, hugely reduced. Roman Catholics have occupied and continue to occupy very senior positions in Scottish society which were, even in my lifetime, closed to them. The appointments of the first Chief Constable or Director of Education, or senior judge who were Roman Catholics were the subject of media discussion. Now, these pass without comment. In terms of sectarianism, Scotland has changed for the better. But, pockets of anti-RC hostility remain. And, it is this which make many practising RCs wary about reducing the powers which the church still has.

The 1918 Act, arguably, was a pragmatic solution to an issue which had oppressed a large section of society and led to a bettering of the status, health and well being of Roman Catholics in Scotland. Perhaps we need a new pragmatic Act, which removes the religious OBSERVANCE requirement from schools but still provides freedom for religious believers to observe, unhindered and free from fear, the principal festival, ceremonies of their faith.

If Christianity was invented today, what problems would it cause a secular society? But since Christianity has its own history, should Christians be left to teach their mythologised version of it to children? Church leaders have been very, very reluctant to expose their own organisational wrongdoings (far too extensive for a brief summary here), and Christians closing ranks have compounded the problems.

And Christianity has virtually no ethics, so why is it being taught by schools as if it does? Obey the Word of God, get rewarded in the afterlife; disobey and be tortured for eternity. That’s mental slavery (ripe for abuse by a hierarchy of ‘intermediates’) and self-interest.

Certainly the permeation of Christian teachings (propaganda) has warped the teaching of many other subjects. For example, we might see the long traditions of ‘heretical’ movements in Europe as more interesting social, scientific and ecological movements without the clouded, distorted lens of Christian theology.

And in practice, proselytising Christians seem to have had an easy job of exploiting religious education opportunities at school or university level to push their own doctrine and silence others. Perhaps this is done even more in England with its ghastly state religion?

https://faithinthenorth.org/for-schools/

At some point, we have to discard traditions we can prove are harmful, and let such religion go the way of FGM, as a mutilation of the minds of children. Although of course far too many children were physically and sexually tortured by Christians and their institutions as well. And Scotland exported many of these abusers out into the world, something we should be reckoning with instead of whitewashing from history.

No ethics? Can there be no ethics if they are predicated on some kind of reward? Arguably all human motivation is predicated on that one way or another even if simply to make someone feel good, they do good. So ethics by that logic, do not exist.

Also, does any religion have ethics then as they all deal with what happens after death in relation to what one does in life?

@Niemand, the arguments about gods and the good predate Christianity, and are summarised (for example) in Chapter 3 of philosopher Julian Baggini’s Atheism: A Very Short Introduction.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euthyphro

The psychological conditioning of Christianity is considered by Baggini, and:

“More profoundly, it is an odd morality that thinks one can only behave ethically if one does so out of fear of punishment or promise of reward. The person who doesn’t steal only because they fear they will be caught is not a moral person, merely a prudent one.”

Christians often seem to conflate belief (in God) with faith and worship; but there is no necessary step between believing in God, being faithful to Christianity, or worshipping God. One could believe that the God of the Bible is a sadistic monster, and refuse to follow the Christian path or to worship such a deity.

The Christian churches in Britain have been largely rotten, abusive, warmongering, ignorance-imposing hierarchies which have spawned and viciously suppressed heresies. Nowadays they seem to spend much of their time apologising for a long and never-ending list of their evils. Since Christianity has been so helpful to European rulers prosecuting their various wars and imperial adventures, followed by the USA with ‘God on its side’, this history is only set to grow. It has been illustrative to hear how many times the Christian God has been referenced in the untrimmed version of Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s The Vietnam War on PBS.

Baggini is perhaps weaker on atheist ethics themselves. To me, a core of come from our shared biology; healthy humans have the employed capacity for empathy, we can intuit another’s pain or good (even if that other is a non-human to some varying extent). Adam Smith covers this in Theory of Moral Sentiments, although it’s far too wordy to bother with these days. We have advanced sciences which give us proxies for measuring health and welfare nowadays. And we can largely measure just how unhealthy various forms of religion are (in some cases, to imperilling life on Earth).

As Richard Dawkins puts it:

‘There are no Christian children. There are children of Christian parents, who may one day choose any or no religion.’.

The same goes for other religions: belief in God doesn’t come naturally to children; instead, it has to be taught.

(It may be no coincidence that human supremacy also has to be learned – young children also grant high levels of moral standing to animals (https://phair.psychopen.eu/index.php/phair/article/view/9907/9907.html), but this decreases as they grow older and fall in line with society’s toxic attitude towards and treatment of non-human animals).

I went to a Catholic primary school.

When I mentioned one day in primary 1 that my Dad didn’t believe in God, my class teacher marched me to the headmistress, who asked me to repeat what I’d said. When I did so, she hit me on the cheek!

Speaking truth to power on that occasion got me a literal slap in the face.

If the Scottish Government continues to thwart a child’s right to freedom from religion, it’ll be a slap in the face to all of us who value freedom of thought and expression, and reject a superstition-based worldview.

It would be nice if you taught children human duties rather than entitlements (aka ‘rights’), some of which you detail and rail against.

Reform’s the party for you!

I very much agree with many of the points of view expressed in this article. I wonder whether religious education should be broadened to include wider issues of ethics and morality. And whether there should be an opt-in, not an opt-out, of religious observance.