Rojava and the Fight for Autonomy

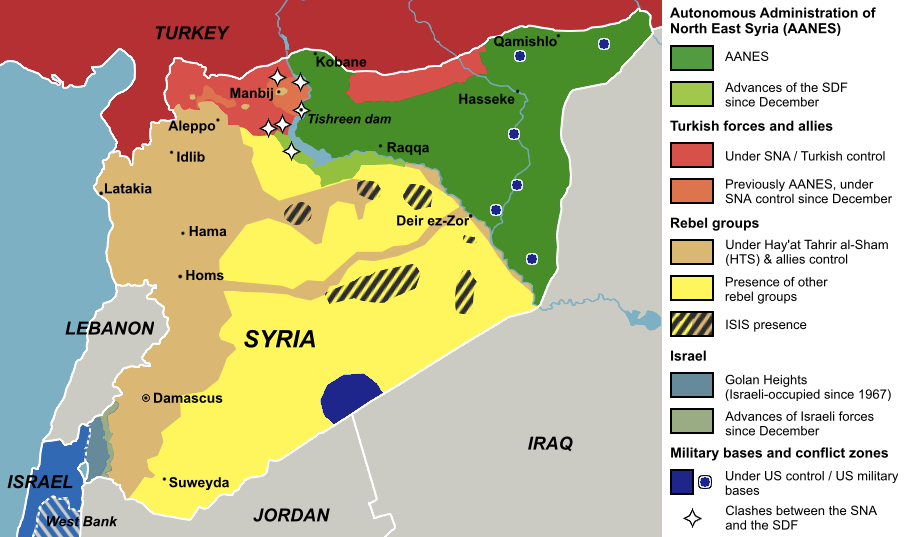

The third of a three-part series looking at the situation in the Autonomous Administration of North-East Syria (AANES), also known as Rojava.

In the West, the change of regime in Syria has been hailed as a great hope for human rights in the Middle East. There is no doubt that Bashar al Assad’s regime was tyrannical and profoundly oppressive: in the whole of Syria, including the Autonomous Administration of North-East Syria (AANES), its fall in December was celebrated with overwhelming joy. However, the new government headed by Hay’at Tahrir al Sham (HTS) is welcomed with reserve and suspicion in the AANES, especially by the women’s movement. The region bears heavy scars from the recent ISIS occupation and inhabitants are very aware of the roots of HTS in Islamism. The fear of patriarchal oppression on the basis of religion is omnipresent, as is the determination to resist it.

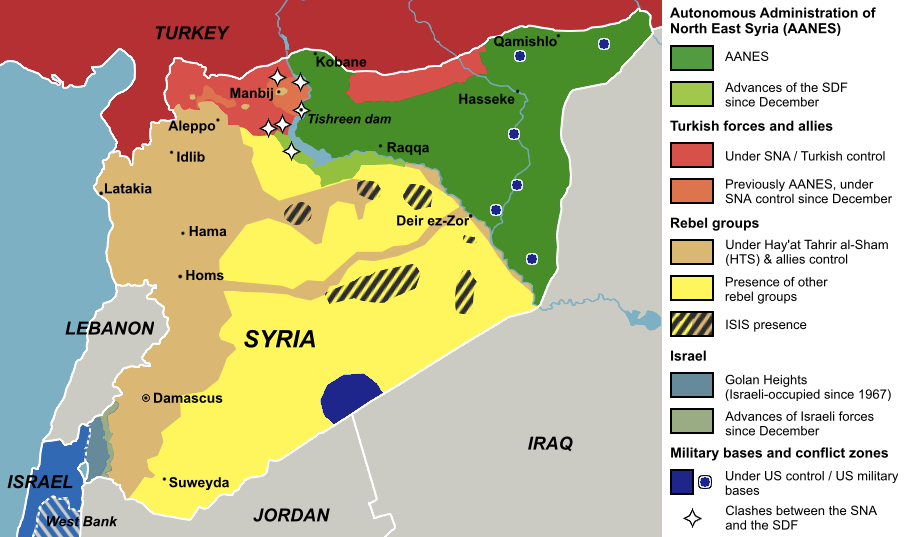

Women of the Women’s Department of the AANES (Siham Kareo and Avin Swaid second and third from the left)

When it declared autonomy in 2012, the AANES was limited to a few Kurdish-majority parts of the North-East of Syria. In these parts, the importance granted by the Kurdistan Liberation Movement to women’s rights was already widely accepted. When the AANES military, including the famous women’s unit YPJ, was pushing back against ISIS in Syria, they liberated a large territory from Islamist occupation. These regions, most of them Arab-majority, subsequently joined the AANES democratic project and the movement for women’s liberation.

Several key processes have been put in place to ensure women’s participation in the administration. All institutions—be they legal, political, or administrative—are presided over by two co-chairs, a man and a woman. Every “commune” or neighbourhood assembly has a women’s committee. There are also self-organised women’s houses, or “Mala Jin,” in every neighbourhood, which handle all gender-related cases, including domestic abuse or inheritance issues, before passing them on to the tribunal if no other solution is available.

Ilham Omar is the founder of a Mala Jin in Qamishlo, with decades of experience in the women’s movement. She explains: “Neither the [Assad] regime nor ISIS were acknowledging women’s rights. … When Assad left, there was hope of a more democratic society, but now the new regime stems from Al Qaeda. … We can’t accept this new regime.” She goes on to criticise the lack of opposition to HTS by US politicians, despite the presence of many American soldiers in the AANES.

Similarly, Bushra Mohammed, administrator of women’s organisation Zenobia, reports a “difficult time, and silence from the West.” She says: “We fear an Islamist state. We suffered under ISIS, especially women, and HTS is [similar to] ISIS.” Raqqa, where she lives, was the capital of ISIS in Syria until it was liberated by the AANES military in 2019. Other Zenobia speakers described the women’s condition during that time as similar to enslavement. They interpret the then obligation to be entirely veiled in black as a literal erasure of their presence from society.

In the AANES, where Islam is only one of the various religions, wearing a head covering is up to individual choice. However, according to Ronahi Hasan, head of diplomacy in women’s organisation Kongra Star, “after [HTS came to power], women have been putting hijabs on again even if it isn’t their culture” out of fear of harassment.

Kongra Star and Zenobia are not officially institutions of the government, but their work is an essential pillar of the administration. Aside from ensuring the presence of Mala Jins and women’s committees in every commune, they also handle women’s cooperatives and provide widespread education for women to reach financial independence. Their courses are also aimed at fighting against polygamy, underage marriage, honour killings, and other deeply entrenched patriarchal traditions.

Hasan asserts that after nearly 15 years of enforcing gender equality in the region, women in the AANES have learned to resist. She describes the new HTS government in Syria as “religious fundamentalism mixed with what was built during the [Assad] regime: people learned fear, they learned not to protest in the street, so now they don’t know how to respond to attacks on their liberties.” In the AANES, however, she expresses trust in civilian resistance to islamism.

The ongoing negotiations between HTS and the AANES are therefore under intense scrutiny from the region’s inhabitants. Avin Swaid, part of the Women’s Department of the AANES, overtly criticised the complete lack of mention of women and youth in the preliminary agreement signed in March between the two parties. She explained that this agreement was signed by two men, but asserted that “in the future, all members [of the negotiations committees] will attend negotiations, with 50% of women.” Swaid stated that the goal of the administration in these negotiations is to “guarantee rights for all Syrian women, not just women of the AANES.”

Siham Kareo, also part of the AANES Women’s Department, further criticises the provisional Syrian constitution published by HTS in March. She says: “The agreement on a social contract [in the AANES in 2011] … was a long discussion that was democratic and involved all minorities, it took two years to draft. HTS took two days to write their constitution, they did not consult the Syrian people.”

YPJ commander Viyan Adar highlights that the constitution “doesn’t recognise women.” It only mentions women’s right to study and work, which Adar considers insufficient. She concludes by telling me: “The struggle is wherever women live. Everywhere, they are subjected to suffering. Our struggle [in Syria] is affected by your struggle [in the UK] too. It is all connected.” In this spirit, there is hope that the incredible achievements of the women’s movement in the AANES will influence Syria as a whole to present a united front against religious fundamentalism.