Live at the (Online) Witch Trials

Live at the (Online) Witch Trials – Student Grant, City Fun and the Two Petes Dress-Rehearse the Twitter Wars on the ‘Right’ Side of History, by Neil Cooper.

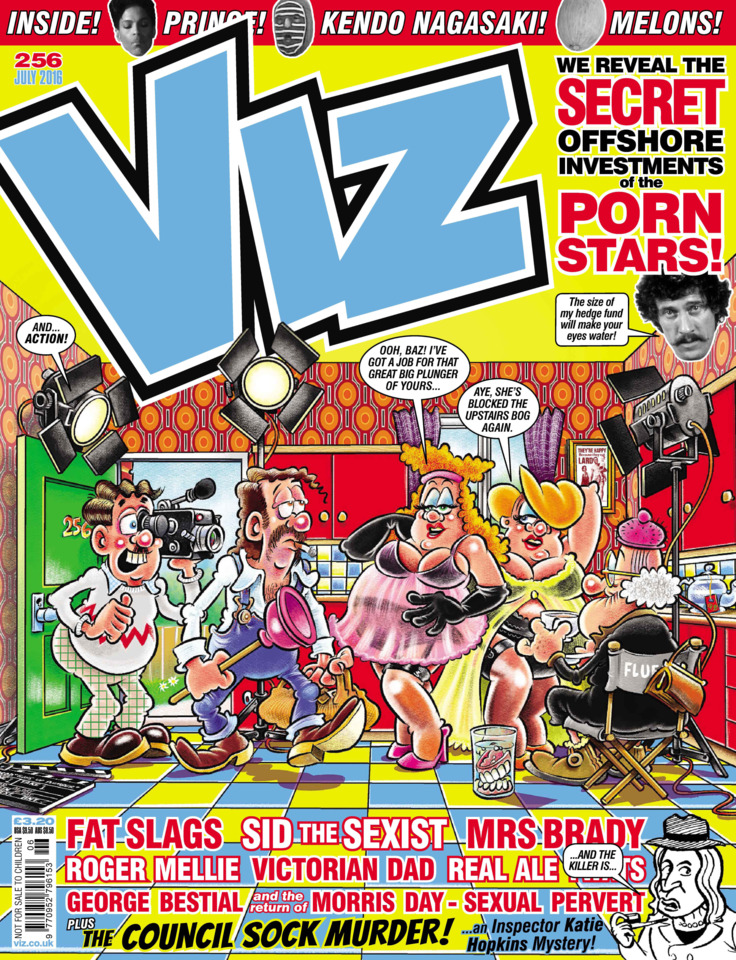

I love Viz. The potty-mouthed Newcastle-sired adult comic is one of my very favourite things in the world. As a barometer of the state we’re in beyond a media/parliamentary bubble, Viz’s satires of unreconstructed British kids’ comics of the 1970s and latter-day social stereotypes are up there with the lyrics of Birkenhead absurdist commentators, Half Man Half Biscuit.

On an entertainingly puerile level, the likes of Finbarr Saunders and his Double Entendres and Buster Gonad and his Unfeasibly Large Testicles have been provoking guffaws among terminal adolescents since Viz was first founded by Chris Donald and his mates in 1979. Back then, it was a DIY zine flogged around record shops and pubs.

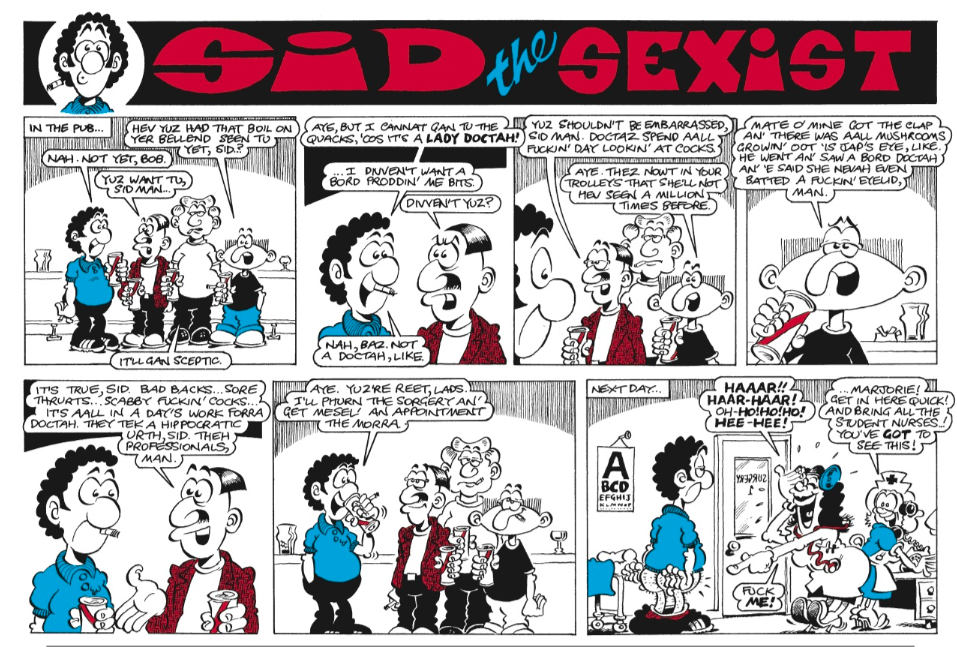

Look beyond such naughty fun, and strips like Drunken Bakers, by writer Barney Farmer and artist Lee Healey, are up there with Samuel Beckett. The Male Online, also by Farmer and Healey, is a withering thumbnail portrait of little Britainites. Then there is Sid the Sexist, the jingoistic adventures of Jack Black and his dog Silver and the octogenarian shenanigans of Mrs Brady, Old Lady. Also a stalwart is Biffa Bacon, the back-street kid who left to his own devices would rather read books and smell flowers, only to be consistently and grotesquely brutalised by his parents.

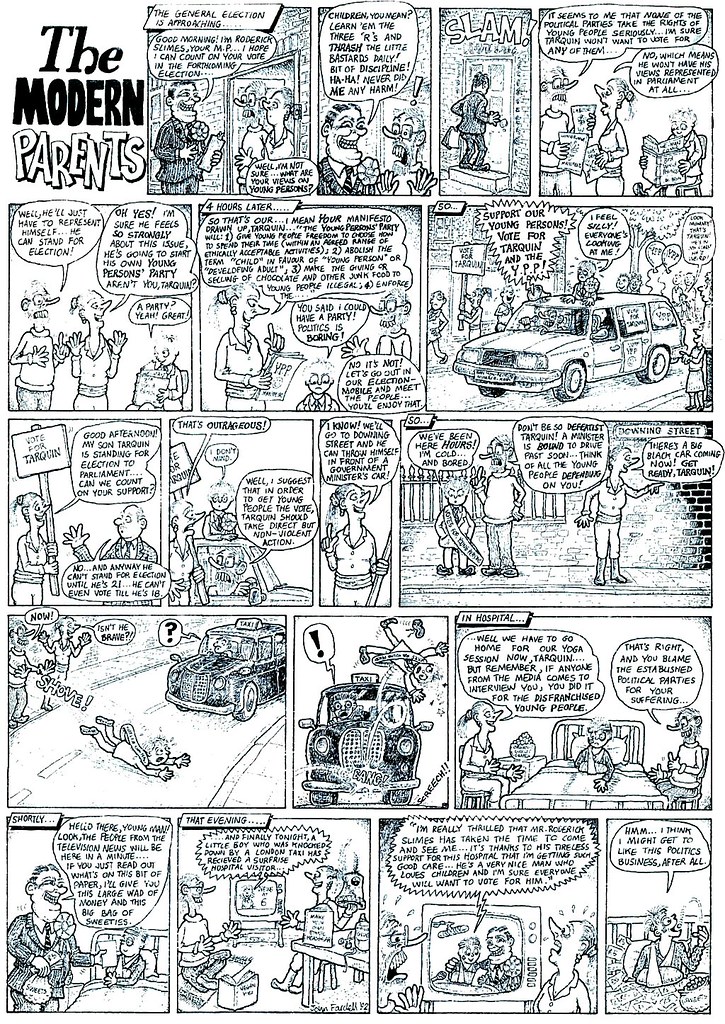

Others, such as John Fardell’s The Critics and The Modern Parents, are sadly no longer with us. Also absent from Viz for several years, presumed to be on an extended gap year, is Student Grant. Created by long-time Viz associate, Simon Thorp, Student Grant’s main protagonist, Grant Wankshaft, is a seemingly terminal under-graduate at the fictional Spunkbridge University.

As his name implies, Grant is an entitled, right-on, pseudo-intellectual know-all who likes the sound of his own voice. Accompanied by his equally dim-witted entourage, Grant will argue the ill-informed toss with his comrades ad nauseam, slumming it in the union bar before jumping on any bandwagon going.

The conversation between Grant and his chums is rapid-fire point-scoring bollocks. The assorted merits of Ali G, The Mighty Boosh or whatever else was big on campus in such innocent times all come under scrutiny. These nit-picking prolier than thou spats erupt into wildly pedantic accusations assorted oppressive forces which have yet to touch on Grant and co’s half-formed lives yet, and possibly never will.

With no one actually listening to what the others are saying, those shouting the loudest bully each other into submission. The gang mentality that develops guilt trips dissenters into kow-towing to the same party line with the fundamentalist zeal of a half-informed convert desperate to be part of the in-crowd.

To achieve such a glorious pastiche in a page-long comic strip that is both funny and insightful is genius. Grant and co do not come out of it well, but they’re probably out there right now, attempting to run the world.

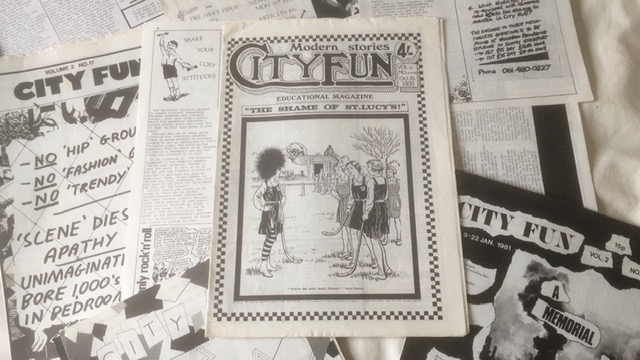

A couple of decades earlier, Grant and his braying compatriots might have ended up reading City Fun. Another favourite magazine of mine, City Fun was a fortnightly zine produced in Manchester from the post-punk late ‘70s to the mid ‘80s or thereabouts. Rather than being akin to the more straightforward cut-and-paste zines of the era, City Fun was as much a community news-sheet on the local music scene, providing gossip, updates on clubs and record labels and gig listings among assorted record and live reviews.

The magazine’s features didn’t bother with mere band interviews, but included reports on local scenes per se, as well as broadening things out to include film and art reviews, and some very opinionated comment. Political with a small ‘p’, it was also illustrated with some of the best collage-based graphic design in town.

City Fun was run collectively, whatever that might have meant at various points of its existence .At its peak, City Fun was wilfully provocative, tribal to the point of cliquiness and at times aggressively snide. It could also be witheringly funny. Despite a self-appointed outsider status that went with its in-built superiority complex, the magazine was an essential part of the very small scene it critiqued.

For those beyond its bubble, the assorted in-jokes and name-drops peppered throughout its pamphleteering broadsides wouldn’t have made much sense. The tone of much of its copy invited the reader to take a side as long as it was that of the editors. While it published letters criticising its contents, its responses beneath were delivered with performative disdain.

In this respect, City Fun’s stance was a more localised version of the music press that then wielded so much power, and whose own morally superior tone had grown out of elements of the underground press. At times, City Fun could be a juvenile bitch-fest wearing its attitude on its golf-ball typewriter. It had the fearlessness of youth at its fingertips, and didn’t give a toss what anyone thought. Publish and be damned, sued or both could have been its motto.

And why not? The magazine’s notion of collectivism ran to not by-lining individual articles, but listing its contributors in a box on its inside cover. Some of those names at different points included a Stephen Morrissey and a Mark E. Smith. Even with such esteemed occasional contributors, given the unlikeliness of any of them being paid, City Fun had nothing to lose except its appearance on the Hacienda’s guest list.

In the days before some of what’s left of the arts press morphed into blanded-out ad-led free-sheets, City Fun’s attitude was nevertheless a breath of fresh air. Its bratty sense of self-importance was reflected in a far glossier way in The Face, ID and, much later, the Modern Review.

Sometimes, as is the way of any publication, City Fun would get it wrong, and they would print an apology or a right of reply. This was the case whether because of unfounded accusations about how the Manchester Musicians Collective spent its money, or a lengthy missive from Factory Records about exactly why it was taking City Fun off its mailing list.

The fact that City Fun in its various incarnations published all this, along with details of internal editorial wrangles, as assorted contributors threw their own toys out of the pram, was all part of the aforementioned attitude. Despite this, as antagonistically nippy as City Fun could be, seeing a magazine own its editorial mistakes in public displayed a sense of responsibility to openness and truth, however grudging. Any serious publication would do likewise.

One of the record shops I bought City Fun from was Probe. Liverpool’s premiere independent record shop since 1971 was based in ornate but crumbling premises that had been customised with a hippy/punk paint-job and smelt of patchouli oil and joss sticks. The shop sat on the cusp of a then shabby Mathew Street, where the ghosts of The Beatles and the Cavern had been blown away by punk and everything that came after at Eric’s club.

Peter O’Halligan’s Liverpool School of Language, Music, Dream and Pun, an arts lab/café where Ken Campbell had staged his 9-hour Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool production of Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson’s Illuminatus!, was a stone’s throw away. Across the street, Bill Drummond and Dave Balfe had set up shop as Zoo Records, home of Echo & The Bunnymen and The Teardrop Explodes, in an office in Chicago Buildings. With all that and more going on around it, Probe was one of the epicentres of Liverpool’s underground.

As with all independent record shops at the time, Probe was as much a social club as a shop. It was a place to hang out, or to gawp at the notice board, where ads for guitarists, drummers and such-like – No Time-Wasters!!! – were posted. You might see photo-copied posters for political meetings, or even a petition calling for local heroes Big in Japan to split up, where the only signatures were by the band themselves.

Probe was a noisy meeting point for punks, freaks and anyone in search of obscure records. At various points local legend Pete Burns of Nightmares in Wax then Dead or Alive worked there, as did Pete Wylie of Wah! Buying a record in Probe when either of the Petes was behind the counter meant running the gauntlet of their scorn lest your choice not meet their approval. You hoped for the best as you blurted out the name of what you wanted, breathing an inward sigh of relief if your purchase was all but flung at you without comment.

The two Petes, however, seemed to save the worst for each other. In an incestuous local scene that had already become the stuff of music paper legend, both lived up to their image. While their peers slagged each other off in the pages of the NME, the two Petes did their sparring on the blackboard in Probe where the new record releases were listed.

Insults were scratched in venomously barbed chalk by one, only for the other to fire back with something even nastier scrawled out. And so it went on, until the blackboard was filled with ever uglier jibes that took Wildean wit and notions of poetic flyting to increasingly murderous extremes.

It might have only happened once, but those lucky enough to be in Probe to witness the aftermath of this could gawp on the pair’s barbaric bon mots left on the blackboard like an artwork. With the two Petes themselves nowhere to be seen, they had left behind a gift tailor-made for suitably scurrilous gossip. As the jungle drums spread around town, it would alert others who hadn’t been there, nor knew what had prompted such an apocalyptic exchange. But, what the hell, they would take sides anyway depending on whose records they liked most.

Eventually, the blackboard would be wiped clean, but those who’d seen it would drink out on it for months. The original tug of words between the two Petes would be half-remembered, embellished or otherwise imagined by those who hadn’t seen it with the demonstrative glee of hangers-on worshipping at the altar of presumed cool. Everyone had an opinion, usually based only on what they’d been told by someone else who swore they were there, despite having been nowhere near the original event.

All of the above are products of their time, reflecting the socio-political landscape that fed them. But imagine all this in the age of Twitter. Imagine Student Grant being a pedantic bell-end about things he knows nothing about, not face to face in the union bar, but online. Then imagine City Fun being called out on something they published, but rather than debate or defend it in public, quietly deleting or altering their original copy without a word. And finally, imagine if the two Petes weren’t hurling attention-seeking insults at each other by way of a record shop blackboard, but in a web forum where the entire world could watch them make arses of themselves.

As even the most casual of social media users will be all too aware, real-life equivalents of all these are just a click away, and have been online staples for years. Latterly, however, it seems to have got a lot worse. The difference too is that, where back in the various days, none of the above would be taken remotely seriously, the dubious democracy of Twitter gives everything a click-baity credibility it doesn’t deserve.

At its best, like City Fun, Twitter is a community notice-board, an irreverent and gossipy talking shop with serious overtones that can be an effective tool for highlighting assorted campaigns or standing up to power. This can be done in-between eaves-dropping on other people’s chat, letting off steam or looking at pictures of cats. It’s also handy, let’s be honest, for promoting articles like this one, and without it the likes of me wouldn’t be able to ply our wares beyond the 280 un-nuanced character limit of our own front door.

At a more insidious level, the consequences of social media slanging matches can be monstrous, and we’re not talking the fake news of delusional politicians and their assorted PR machines or far right hate-fests here. Twitter can be a cess-pool for personal attacks of the worst kind on both public figures and those with far quieter profiles, with personal grudges and professional jealousies weaponised into something far nastier. Such call-outs, pile-ons and faction-based exercises in group-think are the addictive by-product of an online echo chamber that enables a gang mentality with few real consequences.

Like Student Grant and his mates, there is an air that those behind assorted agenda-driven en masse assaults have never quite left the student union, and any real life experience beyond it is likely to be minimal. At times, the advocates of such attacks resemble the proto-sorority girl gang in Arthur Miller’s 1952 play, The Crucible. Here, Miller used the 17th century Salem witch trials as an allegory of McCarthyism, when hundreds of Americans were accused of being communist sympathisers without any factual evidence to support such claims.

At its most childishly trivial, such moral and ideological gate-keeping might mean the odd social media gripe from someone you know concerning your own perceived minor misdemeanours. Instead of challenging you to your face about it, however, they’d rather broadcast it to the world, or their world, anyway.

Given that world is small but public, despite not being tagged into the conversation, you can of course see what they’re saying. So when the person who made the accusatory tweet about you makes no mention of it when you bump into them in the pub a few nights later, the display of mutual fakery that follows as they greet you like their long-lost best mate is a curious by-product of the social media age.

As is too the policing that ensues after being seen to ‘like’ a comment by someone considered to be not part of a particular gang. But this is playground stuff, and, as with Student Grant, arguments in City Fun and between the two Petes, is probably best ignored.

Others haven’t got off so lightly. Name-calling, bullying and attempts to get those offending a particular agenda blacklisted, sacked and outlawed from expressing an opinion are all the rage in the social media arena. All manner of accusations are flung around without any facts to back them up.

Open letters have come and gone. Many are driven by misinformation, and are supported by some who seem to have signed up to them without appearing to have investigated the facts for themselves. Fans of The Crucible might call such incidents a witch-hunt. ‘Twas ever thus, alas, be it among Spunkbridge University under-graduates, partisan readers of City Fun or those keeping a beady eye on the blackboard in Probe.

The two Petes of course went on to greater glories as proper pop stars. City Fun is now an important part of pop cultural history. Only the star-fuckers and Student Grants surrounding them remain. Twitter’s version of Grant Wankshaft and chums may do their growing up in public online these days, but that doesn’t mean the get to rool the skool.

What a brilliant piece.

Thanks, Bram.

City Fun. Ah.. halcyon days. They stuck Sylvia Plath’s ‘Lady Lazarus’ on the cover (superimposed over a blurry snap of German death-camps). Quite the eye-opener for a callow 14 year old like me!

I’ve got that one. Quite the eye opener for me too. I’m not even sure I knew it was Plath at the time.