Humming between Harmony and Dissonance

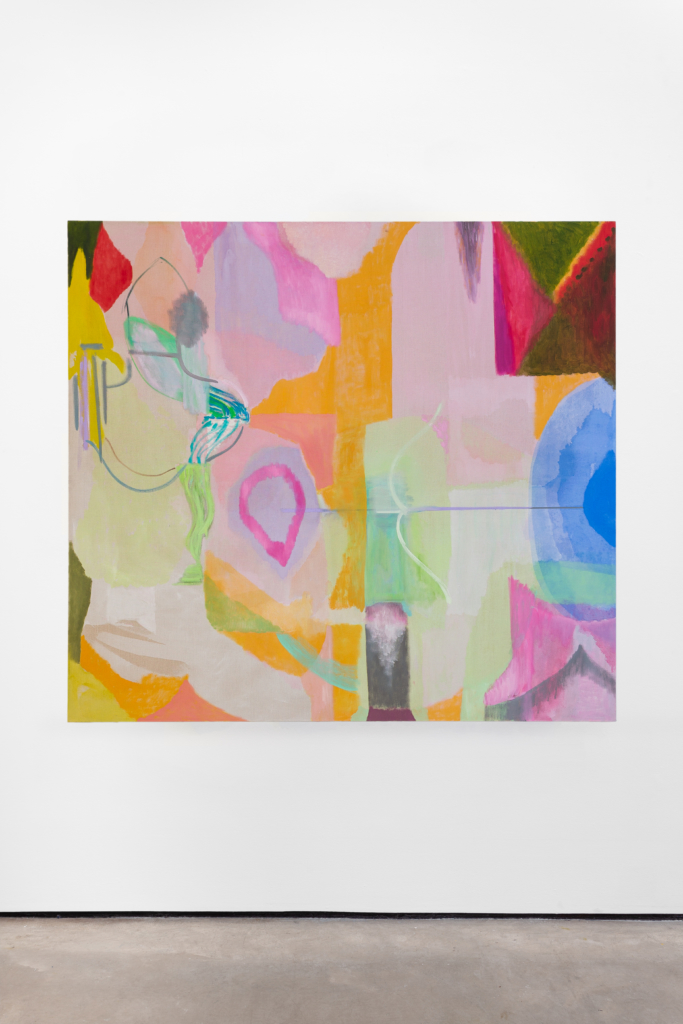

Pedal Point, 230.4 x 215.3 x 2.6 cm oil on canvas, 2021

Interview with the artist Victoria Morton at the time of her exhibition ‘Pedal Point’ at Sadie Coles HQ. by Mira Knoche

Abstract luminous paintings investigating nature, biology, desire, and loss, alongside meditations on musical composition, the psychedelic experience of colour and memory – Victoria Morton’s work is sensual and precise. Born and based in Glasgow, Morton (b.1971) is primarily a painter and musician whose work has been exhibited internationally. With some paintings now held in Scottish national collections, she has become a notable contemporary artist in Scotland and beyond.

I interviewed her in the context of ‘Pedal Point’, her current exhibition of paintings at Sadie Coles HQ in London. In our conversation, she reflected on becoming an artist in Scotland in the ‘90s, her process of making abstract paintings, the eroticism of edges, creating narratives of sensation, and representing female experience in her work.

MK: You studied at the Glasgow School of Art and now work between Glasgow and Italy. Before focusing on your current show, can you tell me a bit about growing up in Glasgow, your connection to the city, and discovering art and music?

VM: (laughs) I suppose like most kids I just liked art at school where we did a lot of art. I also attended the Washington Street Art Centre that ran art, music and drama classes for children from the city centre and Easter House. Then the usual teenage stuff when you don’t fit into the general mainstream… I got very into music. So quite a standard childhood. (laughs)

There were no artists in my family but I was encouraged to go to art school. Then it all kicked in properly. The scene was very different then, no big commercial art scene, it was much to do with people making their own opportunities happen.

There was a really interesting mix of personalities and it was fun. Some thought painting wasn’t relevant anymore and that was a huge discussion. I pretty much made my degree show during the Easter holidays, then Sam Ainsley persuaded me to do my MA. I was on a bit of a roll.

MK: Then you started to exhibit, in the UK and internationally. Was there a turning point in your development when you sensed a leap ahead?

VM: I did a show at Transmission gallery after I left art school which was great. It got picked up by a gallery abroad, so that was the beginning of exhibiting internationally.

Also Andrew Mummery came up from London to see the MA degree show and asked a few people in my year, Richard Wright, Louise Hopkins and others, if we wanted to take part in a group show. Showing in London was important and exciting. Also The Modern Institute started out as a project space in Glasgow and I showed work there.

I was also doing workshops with school kids, small local residencies and collaborative work with friends and Elizabeth Go.

MK: Who were Elizabeth Go?

VM: Elizabeth Go was an art project that involved Cathy Wilkes, Hayley and Sue Tompkins and more. Cathy had a gallery in her flat, called Dalriada, where she did one-off shows in her spare room. It was a tiny space, completely non-commercial where you could show an artwork or one-off installation, which we all did.

Then she invited us to make a collaborative show with her at Catalyst Arts in Belfast. That was the beginning of Elizabeth Go. We did various things after that, performance, short films, before it ran its course. But it was a response to the situation at the time which was quite male-dominated, with a particular kind of art being championed. We were quite keen to present something very different.

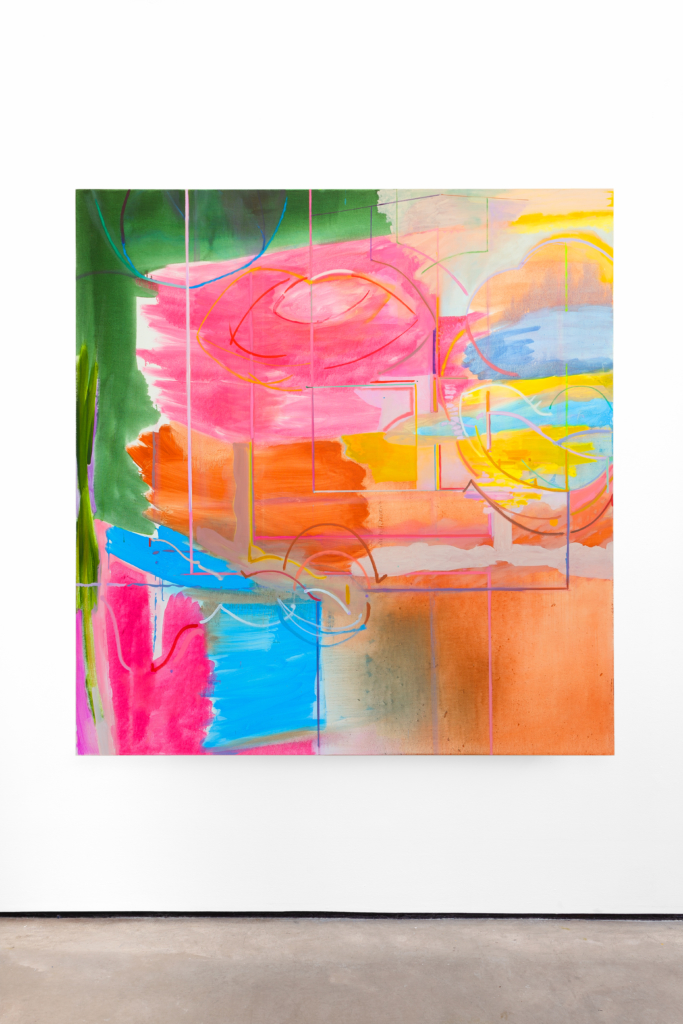

Serpents, 230.7 x 220.2 x 3.7 cm oil on canvas, 2021

MK: And you also played in a band?

VM: Yes, I started making music with friends, playing in an indie band called Suckle. We did radio sessions and toured and it was really brilliant actually (laughs).

It was led by a very strong woman, Frances McKee, who is a bit of a legend in the Scottish music scene. She had been in The Vaselines but also had her own projects going on and this band was one. She gave me the chance to learn to play… two-note bass lines (laughs). I did a bit of singing and was encouraged to write songs.

I also was teaching in Dundee and did a residency in New York and everything was up and running and it was a very busy and exciting time. It wasn’t really about having a career, it was more about having experiences.

MK: It seems like a really vibrant time in Scotland, the ‘90s, in terms of music, counterculture…

VM: Yes, it was – there were good things and bad things. I think it wasn’t as mixed as it is now, it was very much white heterosexual male dominated. (laughs)

I think the scene has become healthier, way more mixed and representative of all different people, and that’s a good thing for everyone.

MK: Focusing on your exhibition ‘Pedal Point’ at Sadie Coles HQ, you are currently showing large and smaller scale oil and acrylic paintings and videos, all viewable online.

Can you describe the process of producing paintings for it?

I wanted to enjoy making work because last year was stressful and, in terms of my process, I can get quite obsessed with making work. So I tried getting work up and running that felt positive and healthy, considering the pandemic and the situation that we’re in. So really I was trying to fall in love with painting again.

Of course, paintings are difficult. A series of problems arise with them all and I have to get very focused in on resolving those.

See more here.

MK: On that note, how do you finish a painting? What is the sense or process of resolving final marks?

VM: I think for each painting, I have a very strong idea of what I want them to do or how I want them to behave when they’re finished. So the process of working on them is really trying to get closer and closer to that. The finishing of them can mean making lots of tiny adjustments and minute changes – or some big dramatic changes.

MK: You have mentioned aiming for “expressionism through constructed composition” in your work – a subtle dance between letting the paint do its own thing, evolving freely, and making deliberate choices. Is that quite a taut experience?

VM: Yes, it’s like a discipline and to do with a very particular and unusual way of thinking. I like the physical nature of making paintings but I don’t just want them to be seductive and look beautiful. They have to have something about them that is inducing a certain experience in the viewer. So I’m really aiming for something specific.

People are responding with their bodies and their brains, their intellects and emotions. I’m trying to engage with all those things in the structure of the paintings. For me that’s about expression but not in the sense of not judging what you’re doing. It’s really considered.

I take a lot of time to make decisions and then there are times when I’m in the right focus and I can make decisions quite quickly. All these contradictory approaches, it’s not a fixed formula. That’s what makes it so interesting.

MK: It sounds like quite a musical approach. Is there a composer or musician that you find inspirational or whose music you could compare to your process?

VM: John Cage talks about chance, I’m interested in that idea and the idea of fine-tuning improvisations. I listened to a lot of music when I was making these paintings, some was beat-driven, some very abstract and strange. (laughs)

One piece that influenced my work at the very early stage was ‘Dream House’, a sound and light installation by Lamont Young and his partner Marianne Zazella which I experienced in New York. That installation really blew my mind (laughs). Once you were inside the room, the work was really inside you. It was a kind of drone built from a mathematical composition, based on prime time tones. When you moved around and moved your head, it would play different tones, and different perceptions of sounds would be teased out of the drones – almost like playing from inside your head.

That feeling of a very extended composition that had no limits, I found really fascinating.

The physical effect of making you feel aware and pulling you apart in all directions was something that I wanted to try and relate to painting. I also started making soundwork after that.

MK: It sounds like tapping into the viewers’ nervous system, almost having a neurological play with them through colour, form, sound. Could you describe your ‘Homework’ project and what ‘Pedal Point’ means?

VM: Pedal point is a musical term, a sustained note that creates harmony and dissonance with other notes above or below. I liked the idea that in my paintings there are both harmonic and dissonant elements.

The ‘Homework’ project was to offer people an entry point to the exhibition, showing them footage of paintings with an up-close view and including music, through an online experience. I took elements of the three large paintings and created music that would work with those. I worked in collaboration with Fraser Muggeridge Studio and Patrick Jamieson on the films.

La Danse, 230.2 x 219.8 x 3.7 cm oil on canvas, 2021

MK: I’m drawn to the painting ‘La Danse’, the vibrant complementary colours and string-like marks that pull your gaze rhythmically between different parts of the painting. It feels spontaneous, deliberate and free. How did this painting evolve?

VM: I started it last year. Seeing the exhibition of Lee Krasner at the Barbican Centre, I was struck by that work. I’d also been included in a show called ‘Surface Work’ about female abstract painters which was a really amazing show to be a part of. I suddenly felt like the way I had been working had a place that made sense.

In this spirit, I was wanting to make fresh work that was really open feeling – and it does feel a bit like a dance when I’m working like that. I’m literally manipulating the canvas and playing with chance, using a very particular colour scheme and then looking at what I’ve got, deciding how to work into it.

For quite a long time it sat in the studio looking quite abstract expressionist and energetic. For me that wasn’t enough. It was too loose and open and I decided to draw the sides of this ancient 16th century dance diagrams I’d seen in the Museum of Bologna, very beautiful but quite structural, onto the surface.

The idea was to have something playful and referencing different artworks from the past, to create something new that was hopefully relevant to today. I often think about the feel of fabric on your skin or a sensual experience as coming from the surface.

MK: A bit of a painter to painter question: could you reflect on the significance of edges within a painting – how they are drawn, overlapping, neat or broken. What does it all mean and how can they be ‘read’ by viewers?

VM: That’s about composition and having an energy or an oscillating effect that creates the brain response we were talking about earlier.

For me the edges, in some sense, became really important, particularly with La Danse where it’s not blended – it’s an area where the edges of two colours almost touch. It’s a game of suggestion and can become quite erotic almost – the shapes that happen, the way they meet and integrate. It can create space and complexity – that push-and-pull effect that Hans Hofmann talked about. I work with that.

The Opening Sex, 230 x 200.5 x 3.7 cm, oil on canvas, 2019

MK: Can you describe what you mean by the ‘psychology of colour’, as in how does colour affect our brains and how does that come into play in your paintings?

VM: Well, that’s a key factor. I’m not a scientist but I’m researching something in my own way by making paintings, the physics of colour, the physical effect and suggestive power. For me it’s about psychedelic experience – not in the sense of psychedelic music, the ‘60s patterns and taking LSD. I mean, I’m interested in that but it’s more to do with a rigorous exploration of the optical effect of colour coming together. Our imaginations and how you can create cognitive responses, depending on the colour that you use and the forms you paint. What you put in, what you leave out.

You wanted to talk about The Opening Sex painting. That’s very much doing that, with quite a detailed combination of line painting and deep space painting. Other suggestions of bodies and forms are hair. I was really trying to get a heightened feeling of female desire, to try and open up a space in a away that’s kind of explicit, but in its own terms. Colour is a big part of that.

MK: In 2019 the Kelvingrove Museum acquired two of your oil paintings, Soliton and Photosynthesis, part of a five-strong series of paintings. One of these was placed next to a Dalì painting. Did that feel like a milestone moment?

VM: I was delighted because I’m from Glasgow and it was my local museum when I was a girl, a long time ago, then my daughter and nieces were going there. So it’s really familiar and I have some favourite artworks in that museum. I never expected to have a piece there because they don’t tend to buy contemporary art, so the fact that they decided to hang it in Kelvingrove was really significant.

And the Dalì, I mean the Dalì is a really kind of over the top piece of foreshortening which I used to go and look at when I was at school, thinking ‘how the hell did he do that?’.

I’m very lucky because my piece is hung on the stairwell with all this beautiful old stonework, the organ that’s on the other side. I love that connection. The sound and sight of Kelvingrove, the smell, you know, everything about it is part of my childhood. So yeah, I’m really glad that it’s there.

MK: Talking about physical experiencing of paintings, are there benefits to viewing exhibitions online or should we reclaim physical experiencing of art where possible – similar to retro reclaiming of vinyl records over streamed music?

VM: Absolutely, I think you can’t replace the actual experience of art. It makes sense for some forms to be online but I think there’s something sinister about experiencing everything through the same medium. I think art should be for everybody, it’s about going into a space, not understanding what you’re looking at and experiencing it, or trying to get your head round it. Having that time is very important.

My paintings are made in natural light and they’re a completely different thing – all the subtleties and complexities and time and thought that’s gone into them comes alive when they are seen in the right conditions. So that’s completely different from seeing them online.

But I also think it’s so important to stay connected with people and to keep things alive at the moment.

MK: Can you tell us about your influences – artists, movements or musicians who were pivotal to your development?

VM: Lots of things influence what I paint – music, reading and art history. In the past couple of years, I’ve been looking at a Russian artist, Natalia Goncharova, and the early modernist female painters who pioneered abstraction, Lyubov Popova and Paule Vézelay, a British artist who went to Paris where she became friends with people like Kandinsky.

I really love the artwork of Sonia Delaunay, who made textiles as well as paintings, and Mary Heilmann who makes these geometric colourful paintings. I’m interested in their multi-disciplinary approach. I also make a lot of different kinds of work.

Looking at medieval fresco paintings in Italy has been influential in terms of working on a big scale, creating a sort of narrative of sensation.

Daphne Oram, 200 x 180 cm, oil on canvas, 2014

MK: The first painting of yours I came across is a rarer figurative painting, held in the National Galleries of Scotland collections and depicting electronic music pioneer Daphne Oram. It’s wonderful to see a painting of a woman pioneering in her work, painted by another pioneering woman. Would you agree that this is still a rare subject in figurative art – especially to be held in a national art collection – that of a female gaze on another woman?

VM: Well, it is, yes. It’s getting better, but historically people that were buying art for the collections, they would not purchase those kinds of paintings. But they do exist. History is being rewritten now which is the best thing that can happen, not just for female painters but painters marginalised for all sorts of reasons.

I can think of times when I visited a museum, for example, the Academia in Venice, and it was really just a …. You know, women were involved in the medieval workshops, which is partly why I’m interested in that period, but as soon as the renaissance hit, it all seemed to change and art became much more commercial. There were women like Artemisia Gentileschi but her paintings were the only ones that I could see in the Academia. So historically, there is a problem.

Obviously, I’m not making straightforward portrait paintings. My interest, when I was studying Abstract Expressionism and postmodern painting, was in making work that followed on from that tradition that represented female experience. That’s a big driving force behind my motivation. Representation to me doesn’t necessarily mean an image that looks like a person. It means representation of all aspects of experience.

MK: Thank you so much for your time.

See Victoria Morton’s current exhibition at Sadie Coles HQ online here.

Victoria Morton’s solo exhibitions include Treat Fever with Fever, The Modern Institute, Glasgow (2019); My Mother Was A Reeler, Etro, London (2016); Spoken Yeahs From A Distance, Sadie Coles HQ, London (2016); Mouth Wave, Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo (2014); Tapestry (Radio On), Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (2012); Inverleith House, Edinburgh (2010); Sun By Ear (with Katy Dove), Tramway, Glasgow (2007); Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn, Germany, 2002; and Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh (2001). Recent group exhibitions include Fieldwork, 42 Carlton Place, Glasgow (2020); Foundation Painting Show, British Heart Foundation, Glasgow International, Glasgow (2018); Von Pablo Picasso bis Robert Rauschenberg Schenkung Céline, Heiner und Aeneas Bastian Hommage à Ingrid Mössinger, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, Berlin (2017); Out of the Frame: Scottish Abstraction, The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery & Museum, Dundee (2016); Devils in the Making, Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow (2015); Generation: 25 Years of Contemporary Art in Scotland, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh (2014); and That Petrol Emotion, Metropolitan Art Society, Beirut (2014). Victoria Morton lives and works in Glasgow.

Further links:

https://www.sadiecoles.com/exhibitions/849-victoria-morton-pedal-point/press_release_text/

https://www.sadiecoles.com/exhibitions/849-victoria-morton-pedal-point/video/

https://homework.sadiecoles.com

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victoria_Morton

https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/artists/victoria-morton

https://www.themoderninstitute.com/artists/victoria-morton/text/

https://www.vogue.co.uk/gallery/london-frieze-art-fair-guide-2016?image=5d54b694b465c00008c4dc79

https://dovecotstudios.com/tapestry-studio/artists-weavers-tufters/victoria-morton/

Photography accreditation for other paintings Patrick Jamieson.

Photography accreditation for Daphne Oram: John McKenzie.