Not nationality but language

Like most people with an interest in ‘the language question,’ I welcome the sudden growth in awareness since the referendum. It’s great that we’re having debates about Scots in newspapers (and here on Bella) rather than specialist journals or thinly populated seminar rooms. The whole conversation feels more accessible and democratic, actually plugged into some of the vernacular energies it tends to champion.

Like most people with an interest in ‘the language question,’ I welcome the sudden growth in awareness since the referendum. It’s great that we’re having debates about Scots in newspapers (and here on Bella) rather than specialist journals or thinly populated seminar rooms. The whole conversation feels more accessible and democratic, actually plugged into some of the vernacular energies it tends to champion.

But the fact that much of the new pro-Scots enthusiasm is fuelled by populist nationalism has its downside too. Alex Massie’s column in The Times earlier this week is right about the current tendency to reduce language to just another front for political mobilisation. It’s always been a shibboleth to some degree, but the question of Scots is now becoming hyper-politicised in crude and distorting ways. As the Edinburgh linguist Pavel Iosad remarked during the last Twitter-spat about this (when The National published its front page in Scots), it’s as though language is just something to have opinions about, a source of ammunition for two entrenched ‘sides’ sniping at each other about something else. There are whole shelves of good books on the history of Scots, Gaelic and the standardisation of English, but they seldom feature in these debates.

The weightless and sometimes clueless quality of these arguments is not only depressing but potentially damaging, tending to shrink rather than expand the expressive possibilities at issue. (And yes, the very weak level of general knowledge about the history and development of Scots – and for that matter English – raises long-standing questions about the education system.) In the larger public arena to which the discussion has shifted, Scots is becoming reduced to a nationalist totem. This has as much to do with how Scots is passionately defended (broadly, as the embodiment of authentic Scottishness and cultural difference) as how it’s attacked by disdainful commentators (as a deluded or sinister revivalism deeply out of touch with Scotland’s overwhelmingly Anglophone reality). As it deepens, this dynamic begins to limit what the language can be made to do – or rather, what the reader/listener is prepared to allow it to do.

So it’s becoming harder to recall that it’s entirely possible to write a Unionist poem in Scots, and that English is by any sane standard a Scottish language too, not some Sassenach imposition from outside. (In case it needs saying, Polish and Urdu and Irish are also Scottish languages in this sense.) Douglas Dunn’s gently polemical verse-treatise ‘English, A Scottish Essay’ has more to say to us than ever before (‘English I’m not. As language, though, you’re mine’), but struggles to gain a hearing when Scots and English are treated as a proxies for constitutional skirmishing. This is more than a shame. There are hugely interesting and inventive things happening in contemporary Scots writing – from Bill Herbert to Jenni Fagan to Matthew Fitt to Harry Giles – but in a ‘literary’ space which feels increasingly remote, and at times out of kilter, with the waving of linguistic flags on social media and in public life. Whatever it is, Scots is more than a badge of affiliation to be kissed or spat on.

All of this being said, ‘literary’ concerns are only one, arguably minor, part of this debate. This issue does not arouse fierce passions because Scotland is full of sticklers for not confusing Edwin Muir and Hugh MacDiarmid (who were famously on opposite sides of the Scots issue). Any number of textbooks or talking-heads can calmly insist that of course there’s no linguistic basis for snobbery about accents, or that standard English is just another dialect of English – the one that ended up with all the institutional authority. The scholarly consensus doesn’t, by itself, address the deeper problem.

I’m not a linguist but it’s obvious that the heat generated by this topic has much less to do with spelling and grammar than with feelings of pride and contempt. As in other parts of the UK, many generations of Scottish schoolkids had it drummed (and if necessary strapped) into them that their way of speaking in the playground or at home was sub-standard, a sign of their inferiority. ‘Linguistic insecurity’ is a bad and baseless thing, but saying so doesn’t instantly cure people’s deeply engrained sense of inadequacy. A more human phrase for linguistic insecurity might be ‘false shame’, which is what the Hampshire lexicologist W.H. Cope called it in the 1880s, observing the first generation of children to come through universal primary education. Cope believed in the standardisation of English but was disturbed to see pupils freshly cleansed of their local speech wincing with embarrassment at the dialect of their parents. Blogs like this can briskly dismiss ‘is Scots a dialect or a language?’ as a tedious, largely irrelevant, borderline incoherent question, and point out that nearly all value-judgments about language are really aimed at its speakers, without ever laying a glove on false shame.

The history of that shame – and of resistance to it – has more to do with class than nationality. But it’s true that ‘improvers’ and standardisers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many of them Scots, associated the spread of ‘correct’ English with achieving full acceptance as North Britons. In A Treatise on the Provincial Dialect of Scotland (1779), Sylvester Douglas (Lord Glenbervie) treats ‘the idiom particular to Scotland’ as ‘a provincial and vicious dialect of English’, and hence, as Lynda Mugglestone observes, ‘particularly open … to the hegemonies of England in linguistic as well as political ways’. The legacy of these ideas persisted much later than we might expect. John E. Joseph cites a schoolroom primer on standard English published in Glasgow in 1960. Under the heading ‘Barbarism’ is listed ‘The use of Scotticisms : – as gigot, sort (repair), the cold, canny’. As Joseph remarks, this ‘amounts to the authors of the book telling its readers that, insofar as the language reflects who they are, insofar as it belongs to them, it is barbaric, and that if they do not want to be perceived as barbarians, they must do away with these features’.

So national identity is undoubtedly part of the picture; but it needn’t be the whole picture. We should question how language is entangled in all dimensions of power, and attend to all the different ways living language can be sneered into silence. It isn’t a stark choice between ‘Scotland speaks English – get over it’ and the dubious idea that the predominance of English-the-language proves Scotland’s perennial victimhood at the hands of England-the-country. Douglas Dunn captures the need to avoid this slippage, riffing on the awkward doubleness of ‘English’:

Not nationality but language. So,

What’s odd or treacherous other than the name?

Not that I like the name – all my bon mots

In somewhere else’s tongue! Why scourge and blame

History for what had to happen in it

When you can’t cancel it, not by a minute,

Not by a year, never mind an epoch?

Go back, reclaim the past, to when we spoke

Each one of us as quintessential Jock?

The quest for a kind of primordial Scottishness via linguistic revival is a dead-end, but we can cherish local and living language in other ways, for other reasons. With every other tongue spoken around us, we can celebrate Scots and Scottish forms of English without insisting that their value inheres in their Scottishness.

There is of course an opposing view. In an essay of 1970 the poet Tom Scott completely reverses Dunn’s view, arguing that

the English language is a record of the experience of the English people and is alien and largely antipathetic to that of the Scots. A writer using English is identifying himself with English experience, is governed and taken over by it, and ultimately not only frustrates his own true nature, but ends up as at best a second-rate writer in that alien tradition. … If Scotland wins free of English power, but is still captive to English literature and language, we have gained only the net the fish has broken from. Our people will still be cut off from their psychological depths by an alien consciousness, still be essentially ruled from London.

This is ‘language essentialism’ in the service of cultural nationalism, taken all the way to its rather chilling conclusion (whereby Scotland can only become fully itself by somehow ‘winning free’ of a language used by 99.82% of its population, according to the last census). This extreme form of language nationalism is rooted in German romantic thought, and an idealised conflation of national language, community and consciousness. ‘The mental individuality of a people and the shape of its language’, wrote Wilhelm von Humboldt, ‘are so intimately fused with one another, that if one were given, the other would have to be completely derivable from it. … Language is, as it were, the outer appearance of the spirit of a people’. These ideas have a very chequered history within nationalist movements, and tend toward the condition Dunn’s poem describes as a ‘Balkanised brain’: a hunger for ethno-linguistic boundaries that will bring the political map into alignment with borders supposedly already there in the souls and psyches of national subjects.

But borders and tongues seldom match up in this way, and we should be careful not to mis-cast English as the red-coated enemy and ‘other’ to Scots. (While we’re at it, pause to notice that there is no single ‘Scots’, but a patchwork of social and geographical varieties.) As Pavel Iosad wrote in the New Statesman, ‘the consensus among academics, if maybe not among laypeople, is that historically Scots is indisputably a sister language of English, sprung from the same Old English root, with a liberal admixture of Scandinavian speech, through the dialects of what is today the north of England’.

I don’t suggest for a moment that we can or should separate language from politics. But it’s entirely possible to validate marginalised language and fight ‘false shame’ without indulging in ethno-national fantasies about English being ‘alien and antipathetic’ to Scottish people. We have spectacular examples of how to refuse this choice – above all, in the work of Tom Leonard – but look also to the work of English-based poets such as Tony Harrison, Linton Kwesi Johnson, John Agard, Kate Tempest, Daljit Nagra. There are as many ways of creatively politicising language as there are varieties of language itself. Flag-waving language nationalism is one of the least interesting out there, and self-defeating to boot.

References and further reading

Scots Language Forum (Facebook group)

Jennifer Bann and John Corbett, Spelling Scots: The Orthography of Literary Scots, 1700-2000 (Edinburgh University Press, 2015)

John Corbett, J. Derrick McClure and Jane Stuart-Smith, The Edinburgh Companion to Scots (Edinburgh University Press, 2003)

James Costa, ‘Language, Ideology and the Scottish Voice’, International Journal of Scottish Literature 7

Tony Crowley Standard English and the Politics of Language, 2nb edn. (Palgrave, 2003)

Douglas Dunn, ‘English, A Scottish Essay’ in Unstated: Writers on Scottish Independence, ed. by Scott Hames (Word Power, 2012)

Matthew Fitt, But n Ben A-Go-Go (Luath, 2000)

Joshua A. Fishman, Language and Nationalism (Newbury House, 1972)

Harry Giles, ‘The Futur o Scots’

Manfred Görlach, A Textual History of Scots (Winter, 2002)

Scott Hames, ‘On Vernacular Scottishness and Its Limits: Devolution and the Spectacle of “Voice”’, Studies in Scottish Literature 39.1 (2013): 203-224.

Wilhelm von Humboldt, On Language [1836], ed. by Michael Losonsky, trans. by Peter Heath (Cambridge University Press, 1999)

Pavel Iosad, ‘What does the Scots language have to do with Scottish identity?’, New Statesman, 11 Jan 2016

Charles Jones, The Edinburgh History of the Scots Language (Edinburgh University Press, 1997)

John E. Joseph, Language and Politics (Edinburgh University Press, 2006)

Billy Kay, Scots: The Mither Tongue (1986; Mainstream, 2006)

Tom Leonard, Definite Articles: Selected Prose 1973-2012 (Etruscan, 2013)

Lynda Mugglestone, Talking Proper: The Rise and Fall of the English Accent as a Social Symbol, 2nd edn (Oxford University Press, 2003)

Tom Scott, ‘Characteristics of Our Greatest Writers’ in Akros 12 (1970): 37-46.

Came to Scotland in 1967 from Australia and was fascinated by language / dialects

Eventually could tell what part of Edinburgh someone lived

That all changed after right to buy council houses as families dispersed

The link tae the Facebook group isna correct, it soud be https://www.facebook.com/groups/126242628908/

A see yer argument, but A think it’s maistly kittle haivers.

Is oniebody really pittin forrit some kinna ‘bluid and muils’ type o argument? Ay, ye can cast thon doon, but it doesna really fire at what’s adae. It leuks fremmit bis the actual discoorse – the troke o it that’s fair farrant and ettled at conterin the general cawin doon o Scots, the nochtifyin o it in braidcastin and in letters (sauf fae the antrin and lang heidit medium o poyems).

We really div hae a problem in Scotland wi language. And we canna sinder thon fae sociology. Ay, Unionists is aye mintin tae homogeneise the countra, acause that gies a heeze tae their political project, and ay, democrats and nationalists is aye castin aboot for weys tae gar fowk feel the differ atween Scotland and rUK, but that doesna mean that thae fowk’s cawin the process. It just means that awthing’s political.

Masel, A div agree wi ye, that ane o the maist brawest things for Scots wad be tae hae Unionists scryin aboot the sair want o Scots in braidcastin and the needcessity for the current tift o things tae be cowpit. But we aw ken it’ll be yon time afore that happens, acause thae bodies has their whip, they hae their threip, and in as muckle as ony ither body that pits their heidmaist politics afore the orrals o whit’s no grand narrative, thir issues’ll maun be pitten by aince eirant their howps o grand victory. The same gings for the ither side, they’ll maun uise wi’ as a wee bit graith tae fire, and nocht mair. But that doesna mean ye devaul fae the ettle. It’s just the strategic situation we’ll maun navigate gin we’re tae see a better situation for Scots, and, atweel, for aw wir national leids tae oxter thegither in harmony wi ilk ither.

Can you repeat that in English please? Thanks. I care about other people’s thoughts & opinions and want to know what you wrote. Thanks.

Pit oan yer heidfones an ye’ll mebbe hear the likes o …

“Whilest I appreciate your argument, I believe it consists of little more than baseless rhetoric.

Is there in fact any suggestion of a ‘blood and soil’ attitude? Oh, you may deny it, but that fails to address the issue. It appears tangential to the substantive discussion — the essence of which is well grounded and intended to oppose the widespread denegration of NorBritSpeak, its marginalisation in broadcasting and literature (apart from the esoteric and intellectual field of poetry).

In NorBritLand we have a genuine difficulty with language, which cannot be detached from sociology. Certainly, Every Patriotic British Citizen would wish to see a level playingfield throughout the Nation, since this promotes National Unity, whereas Rabble-Rousers and Rebellious Elements are continually seeking ways to foster division between NorBritLand and the Loyal Heartland of Our Nation. That does not imply however that any of these factions are the cause of these unfortunate linguistic divisions, simply that everything, at least from their myopic viewpoint, is political.

For my part, I am in complete agreement with you that the greatest advantage for NorBritLand would be fostered were Patriotic Citizens to write concerning the severe absence of NorBritSpeak in broadcasting along with the pressing need for the current situation to be remedied. We are all well aware however that this cannot be accomplished in the short-term. Each of the organisation involved has its remit and its own established agenda. To that extent any such minor requirements will of necessity be subordinated to their more overarching Political Directives; their concerns must be set against the overriding requirement for a Comprehensive Resolution.

This applies equally to the opposition who will simply acquire whatever advantage presents itself. That does not however invalidate their ambitions, it simply exemplifies the current situation which must be resolved should we desire to ameliorate the condition of NorBritSpeak while allowing the full diversity of Regional UnderTongues to flourish in mutual competition.”

Really interesting article. I’m a Scottish writer who writes almost exclusively in standard English with a few Scots constructions I don’t even know I’m doing until my London publisher questions them. (Just for the record, I always refuse to change them.) But I do wonder about that census figure of 99.82%. Not that that’s what the result was, but that the census question was interpreted in such a way that that’s what the result would be. In the same vein, I question the claim that there’s such a thing as “Scotland’s overwhelmingly Anglophone reality”. My uncertainty on both these points doesn’t come from academic research, but from everyday experience, for example on Glasgow buses, and as a children’s writer visiting schools all over Scotland, and, more interestingly, as it can be easily researched, from the number of people who write on Facebook in forms of Scots. They do this not to make political points, but because that’s the way they speak. This hit home to me most forcefully when I joined the Facebook page for old photographs for the small central Scotland town where I grew up. Folk are very chatty on it, and lots of that chat is going on in Scots. But hand them a census form, they’re going to put down they speak English. I notice it too on my son’s Facebook page, where folk chat as if they were in the pub. These aren’t people trying to make a political point, they’re just talking the way they talk and creating their own spelling along the way. The fluidity between the use of the two tongues makes me question that ‘overwhelmingly Anglophone reality.’ (Though then we’d have to start arguing about what you mean by Anglophone…)

Thanks for this, Magi. It could be clearer, but in that bit I was trying to paraphrase the arguments I hear on opposite ends of the debate, with commentators who view Scots as an embarrassing joke often tending to emphasise (and as you say, exaggerate) that ‘overwhelmingly Anglophone reality’. That’s not really my view (which is closer to the experience you describe), but it’s one of the views out there, and seemingly quite an influential one.

On the census: that 99% reference comes from the fact only 0.2% of the 2011 respondents (aged 3+!) indicated that they speak no English at all. 89% said they speak English ‘very well’.

But sensibly the census doesn’t make it an either/or choice between recording yourself as someone who uses English versus Scots. 62% of respondents said that they couldn’t understand, speak, read or write Scots, whereas 38% said they could do one or more of these things. (See p. 10 of the census form to see how the choices were presented – http://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/documents/Householdpre-addressed27_05_10specimen.pdf)

And yes, part of what spurred me into writing this was noticing that ‘Anglophone’ was starting to take on some odd resonances in this debate. It just means ‘English-speaking’ of course, not any kind of preference for English versus Scots, or any associated sense of superiority. (As with ‘English’ in the Dunn poem, I fear the ‘Anglo’ part throws people a bit.) Scotland’s clearly an Anglophone country in that more than 99% of the population can speak English; but that’s not to say the daily speech of the country is 99% ‘English’ as opposed to anything else, or that what census respondents understood by ‘English’ excludes Scottish ways of speaking English, etc etc…

I’d jalouse that the ootcomes fae the census shaw that fowk dinnae ken muckle on whit’s Scots. Parteecularly the passive knawledge; that is acqually a fair feck heicher.

Seems to me that you are trying to legitimise attacks on opponents of the ” cringe”. Shame on you ya bawbag.

And it seems to me that you’re proving my point.

So that means Alex thinks the”cringe” is good? Or the opposite?

It means he seems to think calling people “bawbag” is a useful contribution to a discussion on linguistics and nationalism.

Dinnae agree at all. Unionists do speak in Scots and Gaelic and Indy supporters can have little interest in either. Is there any reader of this article who hasn’t witnessed that?

People will always be moved to respond to chauvinism.

I thought that the article was well written and interesting in parts but light on the fact of place and its importance to any tongue.

Good article. The issue isn’t Scots or local dialect/ language, it’s the way nationalism uses language to divide and entrench power. For old Britain it’s ‘standard english’ but now for ‘Scots or Doric’ it’s the Scot nationalist elite. But the reality is language is fluid. Gadgie, Radge, wor, cannie, muckle, flit, fash, wean (or wee un), bairn etc etc are not ‘Scots’ words but used in Leeds, Manchester, Northumberland, etc etc. They are words of Britain and to deny this nothing but self serving nationalism.

Thir wirds can be baith Scots an in ither Anglo-Saxon spiks. A be blythe at fowk forderin Scouse an Geordie an ither Anglo-Saxon spiks an aw.

Thanks for this. One issue I could have mentioned, but didn’t, was the presence of two language nationalism in other areas of political debate, e.g. the Prime Minister insisting that recent immigrants have to speak English in order to belong in Britain. One reason that policy seems so objectionable to me is that it evokes c19 standardisation.

The only way to promote Northumbrian and Scots would be to allow for a pluricentric view on what language they are. Northumbrian campaigners seem to think that Scots dialects are part of the Northumbrian language and they have a case. I would certainly feel happier having Scots promoted as one of many differing views on what it is rather than the “What is Scots” haverings telling people what they should think about it from certain government financed bodies at present. English speakers across the UK have the oldest dialects and the longest continuous history of speaking what has today become the number one global language geographically and economically used and simply reducing this to “English” and “Scots” is to my eye and ear an absurdity when we consider just how intertwined and gradual their changes and influences on one another through continual contact have been .There are still Scots speakers who speak dialects at least every bit as divergent from standard modern English as anything from Mr Fitt and other online skreivers today and yet do not regard their language as not being English or being part of a language called Scots. This is the heart of the problem with the insistence against seeing the views of some speakers as less valid than others. “Crack” for example, argued to be a Scots English word rather than Scots Gaelic is in fact a Northern English word. This contextualization of what is meant by “Scots” allows for people to see their way of speaking as either being English or not but feel good about it and continue expressing themselves through it with others who will disagree.

As the writer says, he’s not a linguist. He has a lot of the scientific facts back to front.

True, there is nothing wrong with English per se, but language and cultural identity are closely intertwined and reinforce each other. Look at the world map, and at the areas where there are civil wars or separatism. Language has a big part to play.

There is also plenty of evidence that language influences thought. Thinking in English is different from thinking in Scots – or Gaelic – or Urdu or Polish.

And whilst Scots and English are related languages, so are English and German, or English and French, or English and Sanskrit. Language is a continuum.

English is also a continuum. There is no standard, not any more, BBC English or RP is effectively moribund, and we now have phenomena such as Denglish and Estuary English to add to more established versions from India, North America, New Zealand, Uganda, Hong Kong and all the former British colonies. English has become the property of the international community: Japanese speakers of English can often converse much more easily with each other than with a British speaker.

What is a British speaker of English anyway? A Geordie, a Brummie, a Scouser, a Manc, an Ulsterman, a Kentish man, a Cornishman? English regional variation is just as varied as in Scots, yet nobody claims that English is not a language.

No – to rail against the use of Scots as a rallying standard, whilst simultaneously claiming that we’re all English speakers under the skin, is disingenuous and distorting.

Thanks for your comment. Of course I agree about language being a continuum; that was sort of implicit to my point about English and Scots (whatever we mean by those terms) being very closely related, not two distinct ‘things’ in opposed corners of a boxing ring.

Just to be clear, I didn’t claim Scottish people are English speakers (‘under the skin’, whatever that means). Scottish census respondents did (99.8% of them). To be clear, I didn’t point that out to suggest Scots is a tiny or negligible presence in the ‘linguistic ecology’, only to refute the wacky idea that English is somehow foreign or out of place in Scotland.

On the fascinating business of ‘language influencing thought’, there’s a very good article relevant to this debate by Michael Silverstein, called ‘Whorfianism and the Linguistic Imagination of Nationality’, in *Regimes of Language* ed by Paul Kroskrity.

Scott, you’re splitting hairs.

Most of the points you raise are far too complex for this forum – many books have been written on them, as you say.

Take your reference to an article on Whorfian theories. Benjamin Lee Whorf was an anthropologist who devoted his career to exploring the effect of language and other factors on culture, and vice versa. That’s not an area which can be summarised by an online article.

I appreciate that you are working with a limited canvas, but trying to paint linguistic self-awareness as part of narrow nationalism is a clear distortion. Many Gaelic and Scots speakers are opposed to Scottish independence. Many English monoglots are in favour. They are separate issues.

Your suggestion/implication that Scots speakers feel unjustifiedly victimized, and that the independence movement is capitalizing on that feeling, is I feel complete nonsense. The feeling of victimization is completely justified, whether by Scots or Gaelic speakers, whether historically or currently, culturally or economically. Let’s not whitewash the history of pro-Union laws and reforms, from 1659 through 1707 and 1746 to the present day.

However, the independence movement has on the whole ignored the language issue. The fact that those concerned with language see an opportunity in independence to become 10% rather than 1% of the population, or in the case of Scots speakers perhaps even to be the majority in an independent Scotland, says more about the Unionist attitude to language than it does about the independence movement.

It is incredibly hard to over-emphasize the fact that independence is an opportunity for so many things, that support for independence comes from an enormous range of groups and individuals, and that there is absolutely nothing narrow about it at all.

British Nationalism is, of course, quite a different matter, as we are currently seeing with the UK attitude to refugees, immigrants, the EU, non-English speakers, and so on.

Alex, on the same day that you argue that “language and cultural identity are closely intertwined and reinforce each other” Community Land Scotland affirm your view in their newly adopted Gaelic language policy which states:

“Tha FCA a’creidsinn gu bheil an talamh, an dualchas agus an cànan co-cheangailte, agus nach fhaicear, da-rìribh, comas an t- sluaigh ga thoirt gu buil gus an cuirear an luach air a bheil i airidh air cànan nan daoine.” (CLS believes that land, cultural heritage, and language are closely interlinked, and community empowerment can only truly take place where the language of the people is valued and promoted)

Nach eil sin gasta!

http://www.communitylandscotland.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/CLS-Aithris-Poileasaidh-G–idhlig-060216.pdf

(English version also available)

Scotland has had a huge influence on the form and even existence of the English language.

And NOT because of the early English which came to SE Scotland c 650AD which is the usual myth perpetrated.

The main influence on English from Scotland stems back to Malcolm III’s obsession with annexing Northumbria. As part of his personal project to do so which included 7 invasion attempts and marrying a ‘Northumbrian’ princess (who was born and raised in Hungary, hence the apostrophes) he also actively promoted the use of Inglis in Scotland especially up and down the East coast to help that cause.

This was not the early English aforementioned, but Northern English, which by then had already undergone significant grammatical and lexical changes because of Norse/Danish influence from Viking invasion and settlement in the North of England.

In the early days of English in Britain, West Saxon English in the SW and its close relation Kentish in the SE had predominance, largely due to Alfred the Great’s reign. These were both highly conservative in nature and Germanic with the emphasis on German. They were more like old German than modern English.

But the Viking/Danish incursions into the North of England i.e. the Danelaw, brought about the aforementioned significant changes to the Inglish spoken there.

You have to also remember that during Malcolm’s reign England was invaded by the Norman-French who began an imposed linguistic regime of Norman-French there from the top down.

But Scotland had enjoyed a friendly relation with the French and Norman-French before 1066. Indeed Scotland, as well as having a kind of educational exchange program with the French had also invited Norman-French settlers to come here BEFORE 1066, even some of the Brus family (though not close relations to the more famous branch).

After 1066 the Scots continued to have an even closer relationship with France, culminating, of course, with the ‘Auld Alliance’ in 1295. By which time there were many ‘Parisian’ as opposed to ‘Norman’ French words adopted into the Scottish version of Inglis if not so much into Northern English.

This is attested in Barbour’s ‘The Brus’ (c 1380 AD) etc from which professor Duncan estimates there were many thousands of Parisian French words in use in Scotland.

Scotland also developed a well established and prolific tradition of Makars writing in in Scots Inglish.

When Chaucer (Chaucer spent most of his earlier life writing in Latin and French and only came to ‘English’ late on) came along at that time and started to write, with several others, in English in a high profile manner the English they used was not West Saxon or Kentish but the more Northern version from the Midlands northward. Chaucer had spent his youth in the services of the Duchess of Ulster.

However the English of his contemporary Barbour is still closer to modern English than Chaucer and the Wessex and Kentish English which still pertained in the South remained highly conservative.

The first attempt, some reckon, at standardisation of English in England was the advent of Chancery English c 1440 under Henry VI. This met with objections from Southerners that it was full of ‘Scotch’ words.

Caxton c 1475 was also important in establishing ‘standard’ English simply because he committed it to print. He too favoured the more Northern style, despite being a Kentish man himself, and included many Parisian French words in his lexicon, as used habitually by the Makars of Scotland.

The main message here, is that the usual mythologising, that ‘London English’ became the standard and spread throughout the country is highly disingenuous. The truth is that the Southern languages of West Saxon and Kentish in fact gave way to the more Northern, Scandinavian and Scottish(Parisian French influenced) forms. It only has some truth if one sets the starting point at the time of Chaucer and ignores the North to South influence before that.

That is interestin tae hear. Can ye gie ony beuks whaur we can read mair on it?

Even fur the pronoociation, it wisnae the London Inglis but the Oxford Inglis that Standard Inglis comes fae.

Unfortunately in recent years the language issue in Scotland has been politicised by people who deny the status of Scots as a language for blatantly political motives, and who, again for political motives, criticise attempts to foster and extend the use of Gaelic. Then they complain about “nationalists politicising the issue”. They do this in order to promote the Unionist view that there is nothing which is culturally distinctive about Scotland, and therefore in their eyes Scottish demands for self-determination are invalidated.

I wouldn’t agree that Polish or Urdu are Scottish languages in the same way that English is. While I am very supportive of attempts to maintain and foster the use of Polish or Urdu in Scotland, there is no such thing as a distinctively Scottish variety of Polish or Urdu. There are varieties of Polish or Urdu spoken by bilingual communities which also use Scottish languages, but that’s not the same as claiming Polish or Urdu as a Scottish language. Polish or Urdu are languages spoken in Scotland, not Scottish languages. It’s an important difference. In order to qualify as a Scottish language, a language must exist in a distinctively Scottish variety.

Given the typical progression of language use over the generations in community languages in Western Europe, it is unlikely that distinctively Scottish varieties of Polish or Urdu will ever evolve. It’s possible that they could evolve into distinctively Scottish varieties, but Polish and Urdu will probably die out as spoken languages by the third or fourth generation, although their standard varieties may be maintained through education.

There is however a distinctively Scottish variety of Standard English which is well described in the linguistics literature. It’s the fact that English exists in a distinctively Scottish variety which makes it a Scottish language, as opposed to a language spoken in Scotland. Scottish English shares the same phonology as Scots and differs from other Standard Englishes in a number of points of syntax and vocabulary items. It’s the existence of this distinctively Scottish variety of English which allows Douglas Dunn to claim that, as a Scot, the English language is his.

Scottish English, Scots, and Gaelic are all equally national languages of Scotland and as such pertain to the entire nation of Scotland. There’s no law that says a nation can only have one national language. Losing any one of them impoverishes us all.

At no point in Scottish history have Scots ever spoken only one language. Scotland has always been a multilingual nation and it is our multilingualism which is truly distinctive. That’s what we should be celebrating – all our languages, our multilingualism.

There is certainly a variety of Sylheti that is native to Leeds with words such as “belayz” meaning “village”. Its developed over the last thirty to forty years.

Thanks for this. I guess my problem is with valuing ‘our languages, our multilingualism’ on terms where the pre-requisite for inclusion in ‘our’ is being ‘distinctively Scottish’. The open and pluralist-sounding part of this kind of falls down there for me.

Scott,

We are turning in a dense and briared forest of being here. An author I have found particularly helpful in finding my way in the woods is the Canadian political philosopher Charles Taylor, and in particular his important distinction between multicultural and multinational societies (and the related point that I associate with James Tully that one society can be both). After discussing the multicultural perspective Taylor argues that, in the context of Canada, such a view is not enough to deal with the multiple senses of belonging that people are feeling and expressing. He says:

‘To build a country for everyone, Canada would have to allow for second-level or “deep” diversity, in which a plurality of ways of belonging would also be acknowledged and accepted. Someone of, say, Italian extraction in Toronto or Ukrainian extraction in Edmonton might indeed feel Canadian as a bearer of individual rights in a multicultural mosaic. His or her belonging would not “pass through” some other community, although the ethnic identity might be important to him or her in various ways. But this person might nevertheless accept that a Quebecois or a Cree or a Dene might belong in a very different way, that these persons were Canadian through being members of their national communities. Reciprocally, the Quebecois, Cree, or Dene would accept the perfect legitimacy of the “mosaic” identity.’

Charles Taylor, “Shared and Divergent Values,” 1993

Taylor and Tully are speaking in the context of Canada, and in the different ways of belonging to Canada that might be felt by groups with different cultural affiliations within the country, but it seems to me possible that such thinking could be productively adopted to consider some of the thorny cultural questions facing the cultures and nation(s) of the new Scotland. The Taylorian view of understanding diversity in society might help us to form a structure by which we can reassess and reconstruct an open and pluralist (not just sounding but) acting Scotland that can welcome the new while at the same time offering a special form of respect to the indigenous.

Many thanks for this, Iain, which I’ll need to ponder properly. Taylor is very good on some of the relevant philosophical background re authenticity. Cheers.

Ones embarrassment at seeming to be “distinctively Scottish” appears to fit the ‘Scottish cringe’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scottish_cringe

What would you rather be: ‘Distinctively British?’ (another recognised aspect of the ‘Scottish cringe’)

Why is it that Scots universities offer degrees in a number of languages, including Gaelic, but not Scots? Are ‘Scots’ universities also embarrassed at the thought of being “distinctively Scottish”.

The Cringe is indeed strong with this one! I just don’t get it. I lived for seven years in Ireland (just outside Dublin, but the inhabitants of the Irish Republic generally talk about Ireland as one entity, and “The North” as a part of it) – you wouldn’t find many Irish people ashamed of being Irish, nor (except for the extreme Unionists in The North) would they thank you for suggesting that the Irish struggle for independence was a big mistake and they should really ask England to take them back. (I say England deliberately – that’s the perception in Ireland, if not the reality.)

Those who deny the distinctiveness of Scottish language, Scottish thought, Scottish culture and Scottish identity are either pursuing a very outdated version of colonial imperialism, or suffering from delusions of inadequacy. Scotland is different – not better maybe, but different. What is wrong with accepting that?

Of course it is possible to subdivide for ever – one side of Edinburgh’s George Street is very different from the other, so why not have an independent GeorgeStreet-to-QueensStreet between the squares? The reason is simply that there is no popular demand for that, no shared identity, no feeling of distinctiveness.

The reason why countries such as Monaco, the Vatican, Macedonia, and even Palestine exist is because their peoples have a sense of their own distinctiveness, and value that. many people have made it plain that Scotland will be independent when her people feel that difference, that distinction, that need to express their Scottishness.

History has something to do with it – it makes boundaries simpler to draw – but many new countries have been established without the need for a clearly separate history.

These days, at least since the American Revolution, politics and economics are more important than history. That’s why Israel and Palestine, Northern Ireland, Ukraine and other areas are in varying degrees of turmoil. It’s also why Cameron’s new agreement with the EU talks specifically about protections for the City of London – an important cash cow for the UK, and a possible candidate for independence itself. Personally I don’t care whether Scotland would be richer or poorer than England/Wales/rUK – but it’s important to some people.

I don’t see a lot of Palestinians denying their distinctiveness and wishing themselves part of the much richer and more powerful nation of Israel. I suppose they don’t have the same level of inferiority complex as the Scots who wish themselves English.

Palestinians speak Shaami Arabic and it depends on which town or region they come from as to whether they say kahwe, ahwa or gahwa for “qahwat(un)” ie coffee. They are proud to be Palestinians and to speak Arabic in their own local vernacular. They dont perceive themselves as being differentiated from other Arabic speakers by language but by nationality and local history and this is the case for many Scots too. The English who fought alongside the Scots at Bannockburn saw themselves as loyal to the Gaelic kingdom of the Scots despite being an ethnic minority at the time when Scots still meant Gaelic and Northumbrian English native speakers were a minority of non Scottish subjects. Today there are Scots who speak English and Arabic or English and Gaelic or English and Scots who have no cringe when they think of Scottishness but plenty when they think of the way in which Scots is promoted as a separate language from Modern English. This is because they are aware of it being a sociolect and not a language shared across the class spectrum in the majority of areas of the country and this has been the case since the eighteenth century.

Arabic is another complex case, and I’m sure most Palestinians feel a great deal of solidarity for religious or other reasons with Arabic speakers in other countries. The standard Arabic of the Qoran is of course a separate issue. However, that was not my point. I was, rather facetiously, pointing out that Palestinians do not feel so ashamed of their own local language that they choose to identify with their prosperous, high-status, Hebrew-speaking neighbours – although most Palestinians can of course understand Hebrew.

There are Hebrew speakers who use their language to denounce Zionism and to support many ideas such as a single Palestinian state and end to Israel that are the opposite of what the modern version of Hebrew is usually promoted as representing by its political class in Israel and learners and speakers in North America. The code switching thing is less possible in Arabic with Hebrew although they are related. There are certain sounds which would never sit well in the mouth of an Arabic speaker like v and p and the Hebrew pronunciation of “Khamas” for “Hamas” is a clear shiboleth. These shiboleths do exist between Scotland and England but they are shared with many English people too, ie the posh English accent mimicked by Jackie Bird is anathema to my ear and that of many people I would suspect, not only in Scotland but across large parts of England. However due to the dialect continuum between Northern England and Scotland and the Midlands of England etc, English in the widest sense, ie “Anglic” is nearer to Arabic than the difference between Arabic and Hebrew. Just as the Gaelic languages, Irish, Scots Gaelic and Manx are part of a pluricentric language with languages within it. The difference is that in Scots Gaelic at least, (and Im sure in the others too) there is a way to learn how to write and speak in a way shared and agreed upon by other speakers and learners and this allows for them to be treated as separate entities without being viewed as sociolects, which has been the case with forms of Anglic (or English) for centuries now. Thos coupled with the Act of Union, has in my view reduced Scots dialects to a sociolect, apart from arguibly in the Northern isles and Aberdeenshire and a few rural areas less touched until recently by the ideas coming from London and Edinburgh since the Enlightenment.

Danny, I agree with the thrust of what you say, but the details bother me a wee bit. (Wee- Scots or English, or neither? Did I just write Scots? I digress)

First, although I was not really talking about code-switching or diglossia in the Palestine-Israel case, I’m not sure that most of the code-switchers are totally successful. English commentators and voters still know Gordon Brown is a Scot, even if some Scots don’t realise that he is a reluctant Scot. My point is, what’s wrong with being a Scot, and why would you want to switch codes to be English, any more than a Palestinian would want to be Israeli?

Second, switching codes, like bilingualism, is not restricted to languages which happen to be similar. The British Empire proved that, by forcing speakers of many of the world’s major languages to develop an English-speaking persona, for business or professional purposes. In Scotland we have people who happily switch between Urdu and Scots, Cantonese and Scots, Yoruba and Scots, and many other pairings.

Third, the sociolect thing. (Sentence without a verb BTW – and another one – although I’m pretty sure I’m writing English now!) I accept that in Glasgow and Edinburgh, for example, Scots looks like a sociolect – it’s spoken by a particular social group, it’s not used outside that environment much, and most speakers have some degree of code-switching ability or awareness. I’m not sure that this is the case, say, in Lochaber, or Morayshire, or Sutherland for instance – areas where the only real English speakers until very recently have been the landed gentry who visit for a few months to pay wages and kill things, and a few hardy tourists. When the entire indigenous population is deprived, is the language of the deprived still a sociolect?

Finally, all this fuss about Scots, but the last time I was involved in this debate (in the 1990s) there was a similar amount of talk about Doric, and Norn, and probably others. What has happened to those?

Lol, you clearly hate the English. Grow up.

Dé’n Gàidhlig a th’air ‘troll’ co-dhiù?

Tha am Faclair Beag a’ toirt dhuinn “trobha”.

http://faclair.com

Tha am Faclair Beag a’ toirt dhuinn “trobha”.

———

Tapadh leibh. Ach an e sin “trowie”? mmm …

“Ann an toll ‘san talamah bhiodh trobha ‘na chomhnaidh. Cha robh ‘na tholl … ach cha bu chòir leam dé’n t-seòrsa tuill a bh’ann a mìneachadh, ged a bhiodh iad gu math gnàthach aig an aon àm air feadh na dùthcha …”

Tha Dr Moray Watson ag obair air eadar-theangachadh dhen ‘Hobbit’.

Chan eil tuilleadh fiosrachaidh agam, ach chì thu dearbhadh lom co-dhiù fo ‘Further info’ an seo:

http://www.abdn.ac.uk/sll/people/profiles/m.watson

Tapadh leibh, cha robh fios ‘sam bith agam air a shon-sa. Tha tionndadh gus a’ Ghaeilge ann, ach gun a leithid ‘sa Chuimris, nach neònach sin.

‘An Hobad, nó Anonn agus Ar Ais Arís’

(‘The Hobbit, or There and Back Again’)

by J.R.R. Tolkien (Irish by Nicholas Williams, 2012):

“I bpoll sa talamh a bhí cónaí ar hobad. Níor pholl gránna, salach, fliuch é, lán le péisteanna stróicthe agus le boladh láibe. Níor pholl tirim, lom, gainmheach a bhí ann ach an oiread, gan aon rud ann le n-ithe ná le suí síos air; poll hobaid ab ea é agus is ionann sin agus compord. Bhí an doras cruinn ciorclach ar nós sleaspholl loinge, péint uaine air, agus murlán buí práis ina cheartlár.”

http://www.evertype.com/books/hobbit-ga.html

The article hits on one accurate point, at least, which is that although Scots can speak and understand it, English remains an alien language to most of us

The fact maist Scots fowk aye speak juist Scots pruives that Scots is oor mither tongue. Nuthin nationalistic aboot it, juist naitural, an whit sleekit Anglophone Unionists aye seek tae doun-haud.

Ye shuid stick tae teachin Inglis, Dr. Hames!

English remains an alien language?

Then fit why the fuck is this article written in English?? ‘standard English’ is shite. So stop jist spekin the spek, walk the walk, lets see ah article on Bella in ‘Scots’. Lets stop using English at all. Ken fit like loons. Otherwise shut the fuck up and stop moaning.

Nae mere non scots articles.

Dinna forgit ‘proper English’ (aye, an alien language in Scotland) wis garred doon wir thrapple at schuil gin aw the bairns naitural leed wis Scots. Nuthin naitural aboot bein ‘gar-fed’ a furrin leed/cultur. Wi respect, ye’re leukin at this airse fir elbae.

Surely even you, and the author of this misguided article, must realise that being force-fed a single dominant language (English) and simultaneously being denied the thorough learning (written at least) of your own language (Scots) amounts to lingual/cultural oppression, which is/was a common method and theme of colonialism, yet does not conform to international law on minorities/languages today. That is why we had the ‘Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005’ and it is why we must also have a ‘Scots Language (Scotland) Act’.

The cringe is arguably two-parts British nationalist (or unionist) and one part Scottish nationalist – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scottish_cringe

Ye’re richt in sayin there a differ atween the leid poleetics an the independence poleetics. The leid domination is belike stranger. There a link housomiver: I dinnae think fowk wad hae spak o ‘barbarism’ afore 1707.

“When you can’t cancel it, not by a minute,

Not by a year, never mind an epoch?” The Israelis hae duin it fine.

“While we’re at it, pause to notice that there is no single ‘Scots’, but a patchwork of social and geographical varieties.” Lik ony ither leid.

The Israelis have done so but there not a very moral model for how to succeed in language change.

“they’re”

Good article. People are judged on how they speak English across the UK as much as whether they speak it. Scottish people with a regional accent will be judged negatively by the press when they enter and succeed in politics in the same way John Prescott is.

I note that to illustrate the “language essentialism” which he claims is a feature of the current interest in Scots, he has to resort to a quote from an essay written by Tom Scott 46 years ago. I see no evidence that there are significant numbers of people “indulging in ethno-national fantasies about English being ‘alien and antipathetic’ to Scottish people”. That seems to me to be a rather patronising Aunt Sally.

As I say, Scott’s position was (and is) extreme, and unusual for the conscious and explicit way he articulates the ultimate implications of language essentialism. Related attitudes (about Scots being natural to Scottish people and English artificial) are certainly not scarce today day – see elsewhere in this comments thread.

If it’s an “extreme position” taken in 1970 by a writer who died in 1995, I’m finding it difficult to understand what there is to fret about. The Scots language activists I have known over the last 40 years have been concerned with extending the range of Scots in prose, poetry and drama, not denying the conspicuously secure place of English in the culture of Scotland. The over-heated and ill-informed froth of the twittersphere and comment columns is neither here nor there in this context.

Graeme Purves, you said that you “see no evidence that there are significant numbers of people “indulging in ethno-national fantasies about English being ‘alien and antipathetic’ to Scottish people”.

Commentary along those lines has been heard more recently than 46 years ago. For instance, there was Alf Baird’s earlier comment in this very thread that “that although Scots can speak and understand it, English remains an alien language to most of us” and his later comment “Dinna forgit ‘proper English’ (aye, an alien language in Scotland) wis garred doon wir thrapple at schuil gin aw the bairns naitural leed wis Scots. Nuthin naitural aboot bein ‘gar-fed’ a furrin leed/cultur. Wi respect, ye’re leukin at this airse fir elbae.”

Lets continue to focus on the English language Natalie, as distinct from the English people, not that you would wish to make mischief unnecessarily.

But as to my statement, which you quote, do you deny that the English language wis garred doon the thrapple of Scots at schuil?

“do you deny that the English language wis garred doon the thrapple of Scots at schuil?”

The “do you deny” style of debate is always such fun! Do *you* deny that the natural mother tongue of many Scots is English? You talk of the thrapple of Scots as if “Scots” were one entity with one throat. Scots are a lot of people. Some of them had English forced down their throats, some of them absorbed it with their mothers’ milk.

“some of them absorbed it with their mothers’ milk.”

They had little choice. They still have little choice. Hence the word ‘forced’/’garred’. Hence the word ‘oppressed’. Hence the term ‘cultural racism’, which you and your ilk advocate.

You seem to have skipped over my final sentence. My clear reference is to ‘significant numbers of people’ and you quote me an instance in a comment string! Do you work for the ‘Daily Mail’?

The proposition that English is antipathetic to Scottish expression is so patently absurd to anyone with the slightest acquaintance with Scottish culture that it needn’t detain us for a second, whatever others have claimed in this string. James Hogg, Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson and John Buchan all had excellent command of the Scots Ianguage but made their substantive contributions to literature in English. Are we going to reject them as alien, antipathetic or inauthentic in that ground? I hardly think so! I am antagonistic to Scott Hames’ invocation of “linguistic essentialism” because it is an obvious Aunt Sally designed to further his spurious Spartist analysis. Pace Mr. Hames, this is primarily about national identity. There is an important class dimension, but Scots was beaten out of middle class kids as well, and with more success. Borders and tongues often match up quite well, particularly where the national border is as stable as Scotland’s has been. The reason that Scots has not consolidated itself as a modern European language like Finnish, Norwegian or Latvian is that it has had no state to champion and defend it.

“The reason that Scots has not consolidated itself as a modern European language like Finnish, Norwegian or Latvian is that it has had no state to champion and defend it.”

Well said Graeme, and I would go further in that the British state has intentionally done all it can (in over a century of state school provision, and via the msm) to diminish and discourage the Scots language, which is much in line with established strategies of colonial powers. Holyrood has largely been complicit thus far, as evidenced by the passing of the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act in 2005 yet not giving equal treatment to the more widely spoken Scots language, which is effectively discrimination.

Graeme Purves, you write, “My clear reference is to ‘significant numbers of people’ and you quote me an instance in a comment string! Do you work for the ‘Daily Mail’?”

No, like you, I write for free in blog comment threads – and other places where public debate takes place on subjects that interest me, which includes the survival of minority languages and the politics thereof. Do you really value what we are both doing here so lightly? I hardly ever agree with Bella Caledonia on politics, but it is one place where you can find regular discussion of this subject, relating not just to the languages of Scotland but worldwide, and aimed at a non-specialist audience. I’d say it is quite an influential centre of debate on the future of Scots and Gaelic.

I agree with your views on the absurdity of the proposition that English is antipathetic to Scottish expression. But when you say that there is no evidence of significant numbers of people with the opposite view it’s not unreasonable to point out that there are some right there in the same room, metaphorically speaking. Scott Hames wasn’t setting up an Aunt Sally.

Its not how you speak it is about the content,is it sensible and meaningful that is for me of more importance,haven,t we had our fair share of Oxbridge people of so called prominence that spew a whole load of bollocks/lies but it is good Queens English.

Most Portuguese people can read and understand spoken Spanish. That doesn’t mean it’s “their” language, or that it’s not “distinct” from Portuguese. Both languages exist in an enormous range of local varieties too, and I imagine most Brazilian Portuguese speakers can understand most Peruvian Spanish speakers. But the languages, and the cultures they support, are distinct.

The same is true, I believe, of Scots and English.

Switzerland has a bewildering number of languages or dialect s which are not mutually comprehensible, but it holds together as a country for some reason.

Spain is busy splintering along language frontiers, but the driver in most cases is not support for Catalan, or Basque, or Gallego – it is a sense of identity, and perhaps economics too.

The “phonetic Scots” crowd seem to think that verbal and written language are the same thing. They are not, though obviously they overlap.

We typically use just a few thousand words in speech. We use hundreds of thousands in written language. With one or two exceptions maybe, nobody in Scotland has a greater mastery of Scots than English. Get a Scots speaker to articulate an even slightly complex idea, and he will soon resort to English. That was exactly Muir’s contention with MacDiarmid, and it ought to be noted that MacDiarmid ended his career writing poems in English, or Scottish English, in which he articulated highly complex ideas…

If you cannot articulate complex ideas in Scots, then effectively, today, as things stand, it is a dialect. There’s nothing wrong with that necessarily. But with the exception of some of the vocab, there is not much that is interesting about it either. What is interesting about languages is the different world views they offer the learner. And what is brilliant about Scots is its vast and so expressive vocabulary. But almost nobody knows more than a handful of words of it.

Besides all that, the other day, The National published an article in phonetic Scots where there were sentences which even merged the verb with the noun – presumably because people often do that in speech – thus breaking one of the basic grammatical rules of every single European language: grammatically it is gibberish.

This idea that you can write Scots just as you please, which people like Mattehw Fitt are peddling, will be the final nail in the coffin of Scots. The words author and authority are etymologically linked, they have the same root. If there is no “authority” behind the language, then people find it hard to take the “author” of even a newspaper article seriously.

Writing was invented to increase powers of human expression, and for collective memory. I can’t see how the phonetic Scots crowd are going to contribute to that. I think Scott Hames underestimates the amount of Scots people speak in working class Scotland, but I also think the phonetic Scots crowd are confirming Scots as a dialect.

In any case, this is all about social class, let’s not kid ourselves. The Scottish middle class speak Scottish English, and the Scottish Working Class speak a degraded and much depleted version of Scots, though obviously it is a spectrum. The Edinburgh middle class would tell you to go and wash yer mouth out with soap and water, for speaking “the language of the gutter”…I mean that’s what they would say to you at school or wherever…

…they don’t have that massive problem in other minority linguistic communities in Europe, like Catalonia say. And it is why the SNP won’t make Scots a nationalist cause….

..that people associate social injustice with standard English is a conclusion which on the grounds of logic is unimpeachable….which doesn’t make it right. People who speak Scots are far more likely to live in poverty than people who speak Scottish English….

“the language of the gutter”

Not so RG, read Nick Durie’s contribution above to see the eloquence, sophistication and extensive vocabulary of the Scots language. To reach that standard would be a joy for many Scots, not least myself. Wha cries ye hae need o mony wirds onywey? A wheen o angersome fowk blether galore yet say naething interestit, like a oor glib middle-cless heid bummers an politeecians, an massie academics tae, like thon Canadian gadgie Hames.

It’s interesting. I grew up speaking Scots, like many working class folks posting in this forum. My family still does. But I can’t understand must of these comments written in ‘Scots’.

But surely it’s another nationalist drive to be insular. After all, shouldn’t we be reaching out to the world in the lingua franca which is English. What good is it to speak in this dialect if no one outside if it can understand?

Alf, I am not saying Scots is “the language of the gutter”, I am saying that I had teachers who would say that to me at school in the 70’s and 80’s…obviously I don’t think in those terms about any language.

Nick Durie is not a phonetic Scots advocate, he is a Scots Leid advocate or a Lallans advocate. If only the 1.8 million people who declared on the census that they spoke Scots, spoke it as well as Nick Durie does, or as well as Tom Scott wrote it, or MacDiarmid or Robert Garrioch did….but they don’t, and most don’t have any interest in Scots in those terms.

Their sole interest is expressing the spoken word phonetically, and even there, there are no rules to be followed apparently, it’s anarchy… Matthew Fitt says, just “express yourself”….there’s no harm in it of course, but you can’t take a written language seriously in which there are no rules at all. It’s not going to be able to communicate much compared to other languages, because it does’t go beyond how people speak…

Folk like Tam Leonard laugh their cap off at people like Nick Durie and their efforts. The Scots / Phonetic Scots language community is itself divided, almost certainly on class grounds…

As for the census figures, they merely illustrate how confused so many Scots are about language and the Wee Ginger Dug is totally right to reject the ridiculous notion that, just because we have Polish or Urdu speakers in Scotland, that makes them Scottish languages… the kind of absurd cap in hand thinking that has bedevilled Scotland since 1707…

Yes and yes and aye. Perfect comment, so right.

So many assertions, so little fact.

It’s not true that having to resort to other languages to express certain ideas invalidates a language. Most of the world’s languages resort to English some of the time, and some of them do so a lot – German and Japanese for instance.

English still resorts to Latin (law), Greek (medicine), German (psychology) and French (cooking) to express many complex ideas.

Irish lacks a technical vocabulary, and I imagine medical and other words, yet it is an official state language and is both a subject and medium of University courses.

There is a Scots dictionary, but it is incomplete and under-resourced, so many people resort to phonetic spellings. Inability to understand these may mean that you are not a member of the right group, or that you are not motivated to try. I’m not a Scots speaker, but I’m coping in most cases.

European languages do not all distinguish strictly between verbs and nouns, Indeed English itself is ceasing to do so. But certainly sentences without verbs are common in many written languages, and spoken language is much freer. Languages like Italian or Basque use verbs in quite different ways from English. As my teenage son would say, do you even grammar?!

Many languages, like many prophets, are not adequately recognized in their own countries. There is a furore in Ireland at the moment because the national broadcaster is not organising pre-election debates in Irish. The fact that almost all Irish speakers can also understand English is simply not the point – it’s a degradation of the status of a language which is part of the identity of many people, and a prejudice of the ruling classes against a culture which is not theirs but which is valued and admired worldwide.

This is not about being insular. This is about being true to yourself, preserving your heritage, and keeping a unique and distinctive world view which is valuable to everyone. Most languages are actually only understood in their native country or region or even village – it’s a sad fact that there are more than 2500 endangered languages globally, with almost half of these having fewer than 1000 speakers.

Imagine if all writing, all culture, were only available in American English or Chinese.

Imagine if all mammals which were not farmed for food were simply wiped out.

That’s what the “language of the gutter” attitude supports.

Alex, one thing we do have in Scotland are excellent Scots dictionaries….

http://www.scotsdictionaries.org.uk/

…it’s just a pity nobody bothers their arse to open them now and again.

I cannot think of an example in any European language I know where people express the verb and the object of the verb in the same word….Italian you say? Not so, completely untrue…

That is not how European languages work, and they all share the same linguistic root, with the exception of Basque and, I think, Hungarian and Finnish. They all follow the same basic rules, with a number of complex variations in things like word order and case.

I don’t share Scot Hames concern that language is being used to divide people at all in Scotland, because it always has done, just now one side is fighting back.

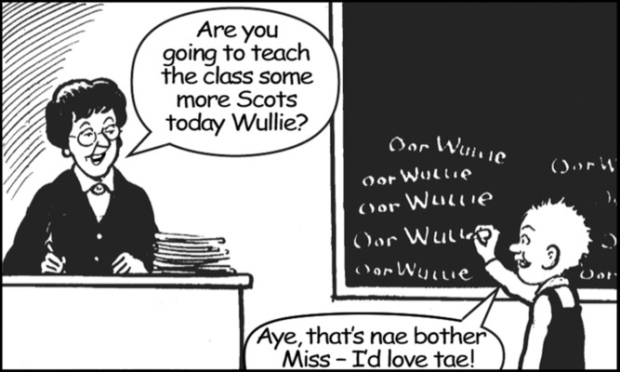

What does worry me is the intellectual poverty of phonetic Scots, which more often than not, is used to express a kind of defiant, sentimental “wha`s like us” sense of Scotland, the rehashed kailyardism of our times….an Oor Wullie Scotland which is completely inadequate for self-expression beyond the spoken word, and is further confirmation of Scotland’s long standing hostility to the slightest whiff of anything intellectual….

“Scotland’s long standing hostility to the slightest whiff of anything intellectual”

Nowadays many more Scots realise that its little more than gas we often get from our well-spoken ‘betters’ (the article above being a case in point) who when encountering immense difficulty with even pronouncing a word (e.g. ‘Calder’) often merely changed it to something they could pronounce (i.e. ‘Cawdor’) withoot chowkin thairsel wi thon bools in thair mooth.

Are none of the ‘intellectual’ anti Scots language lobby up for responding to the well-established principle that: “The …colonial process includes the oppression of language model”?

Alf, where is the oppression here re Scots? Culture is a devolved power, the SNP claim to be a national party, so take it up with them, and less of yer havers. They’ve been in power 8 years now, nobody is stopping them from passing a Scots Language Act or whatever you want to call it. Try sending a letter to oor Fiona Hyslop before you go rushing off to the United Nations…

The SNP won’t turn Scots into a nationalist issue because Scots is spoken primarily by the working class. The SNP are not a working class party, and hence they shy away from it, possibly they are right to, given that the people who call for Scots to be taught at school, can’t agree on what Scots actually is….

It’s up to the young people to decide whether Scots should remain what is essentially a dialect, or instead become a fully-fledged national language, which of course it could be. The obvious answer is to come up with a standard form of Scots which combines the best of urban, contemporary Scots with Lallans…ie, a synthetic Scots, but no less synthetic than Gaelic is synthetic or Basque is synthetic, or Hebrew is synthetic….all those languages have a standard form which has been agreed upon by pooling all the different dialects together and coming up with a standard form that can be taught…and it doesn’t mean people can’t speak the way they like, but it does mean they all write the same…

RG – you claim “The SNP are not a working class party” – I think you may find that things have changed. Or do you really believe that 115,000 party members and 1.5 million SNP voters are all “tartan tories”?

Where have you been for the last 3 years?

Do you still believe Labour are a working class party?

What about UKIP?

The problem is you get mocked for trying to write in Scots when its not the way people speak. This leads to a dilemma with such words as “modren” and “richt” which simply arent used in Edinburgh every day by ordinary people who nevertheless say “aye” “dnnae” and “ken”. Other terms like “doag” are argued by some to be the modern local variant of “dug” and the Glaswegian sounding speakers in BBC Scotland’s “The Scheme” are looked down on by traditional Ayrshire speakers as being outsiders from Glasgow’s overspill. There is in fact a snobbery within the Scots language movement as much as within English in the UK inclusive of Scots and this needs to get sorted out by a standard artificial written form being created officially and taught in schools if it has any chance of once again becoming an actual language as opposed to a version of self guided written English.

RG, I don’t know your background, but you are at risk of teaching your grandsire to suck eggs here. Let me nail my colours to the mast – I have PhD in linguistics from the University of Edinburgh, and have been thinking about such things professionally for over thirty years now.

English verbing of nouns is a well-attested phenomenon, culminating as I said in the current teenage generation’s derisive responses such as “Do you even Apple?”

Italian and Basque, and other languages, have a notion of ergativity which blurs the distinction between nouns and verbs, since the verb no longer relates to the doing of an action in the same way.

Latin has/had several ways of verbing nouns, including the popular gerundive constructions which have passed into successor languages including English, French and German.

Sentences without verbs are common in speech, and certainly in colloquial writing (which is what most written Scots surely is) in most European languages. Here’s a recent example of Portuguese from my page on Facebook, the first example that springs to mind – pick the verbs out of this if you can. “Que coisa mais fofinha!!! Vejam como brinca!!!! Que amor, gente!!!!”

I’m not a great fan of Chomsky’s linguistic theories, but he did make the very important distinction between grammar and performance. Many linguists argue that performance is actually more essential to language, and certainly in the case of English the formal grammar of the written language is very different from the day-to-day performance of most speakers. Scots simply lacks the artificial imposition of formal grammatical rules on the written language – as do most of the world’s languages.

I’m afraid speakers of English, even if they have mastered the formal varieties of other European languages, have little grasp of the reality of languages which have limited or no use for the written form – which covers most of the world’s languages, and probably most European languages too. English is an anomaly, as the UK is an anomaly. Scots is much more “normal” in many ways.

As I said earlier, this is really too detailed for such a forum, so I will not comment further. Just bear in mind that Irish (as good a language as any other), despite being arguably the first widely written language in Europe, has no standard form, no standard grammar, no complete set of rules for spelling, pronunciation, agreement, word order, etc. Yes, it’s basically a VSO language, but beyond that regional variation takes over pretty quickly.

What’s the English word for ‘hippopotamus’?

There is no body in England or Westminster stopping the establishment of a Scots language standard orthography. This is down to the national government in Edinburgh. They view it as a sociolect and hence “divisive” as someone else here has suggested and avoid making it a subject for serious discussion.

Very few languages have their orthography/spelling or other features laid down by government – and for those that do, it rarely works.

Language evolves, and if Scots speakers want a standard orthography, it’s up to them to develop one. As with independence, if enough people want it, it will happen.

The alternative is to get some academic to do it, but then how do you get people to adopt it? Look at the Concise Scots Dictionary – a great piece of academic work, but outdated before it was finished, and never likely to keep up with change.

To be fair, English has the same problem. The OED is reactive, not proactive, and certainly not proscriptive.

Exactly 😉

Alex, if you are a linguist, then you must know that GOVERNMENT doesn’t lay down orthography, LINGUISTS do, experts in language who usually form part of an Academy, in countries like France, Spain and Portugal, to name but three, though I could say Catalonia and the Basque Country too – the Euskalzaindia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euskaltzaindia- not to mention Galicia.

In Britain they don’t need an Academy because they have the Oxford and Cambridge dictionaries, which effectively decide which new words get into the dictionary each year…and the moneyed private education system which has always decided what is “correct” English and whose dons have produced countless primers….RP…received pronunciation, effectively the passport to the corrupt network which is UK PLC….

…the English don’t need an Academy, they have countless factories of RP English.

If people want to believe that Scots is going to survive the Anglo-American media empire on their screens every night and their ipods every morning, fine by me. I think the chances are almost non-existent. You either have a standard form or a) you can’t teach it b) you can’t measure how widely it is spoken – the census is all but meaningless in my opinion and c) no foreigner can learn it unless they live for years in Scotland;, or is Scotland sae braw that outsiders arriving in the country automatically know the vowels sounds not just of Scotland, but all its different dialects, so as to be able to understand phonetic Scots?

I don’t think most people in Scotland really care about communicating with anybody but themselves when they write in phonetic Scots…and you have almost no vocabulary beyond what is spoken…so tell me how you are going to write a philosophical treatise in Scots? Or an engineering book? Or even an IKEA instructions manual?

Languages are dying out by the hundreds every year. The only ones that have a chance of survival are those which take their language seriously and protect it, like the Catalans, one of whose national heroes is a grammarian…Pompeu Fabra….https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pompeu_Fabra

We should change the name of the country to OorWullieland….the Scots, the nation that swapped a language for an accent…

Alex Monaghan states:

“Irish lacks a technical vocabulary, and I imagine medical and other words, yet it is an official state language and is both a subject and medium of University courses”

——-

Far too bleak a statement particularly given recent extensive lexical expansion, perusable at:

http://www.focloir.ie

http://www.tearma.ie

Moreover, in Dec 2015 the decision was made that by 2022 Irish should function as a full European Parliament language. Trainee translators are consequently now in demand. “Technical vocabulary” will be unavoidable:

https://slator.com/demand-drivers/ireland-ramps-translator-hiring-irish-gaelic-gets-nod-eu/

Fearghas, thanks for this information. I’m not saying that progress is not being made, but for example, I was close to the Fiontar project around 2000 whose objective was to create an IT and business vocabulary for Irish. By the time that project ended, a small number of Irish speakers were aware that the Irish word for software was now officially bogearraí, but that won’t have reached the general population for a while.

The same is obviously true of more recent projects. Whilst EU translation will help, a limited number of people will read the more technical documents in Irish, and the spread of new vocabulary items will be slow and unsteady.

It is also worth bearing in mind that in French, where the official language is controlled by a government body, new words are often created but less often adopted by French speakers. One example is “sonal” – an audible alert, analogous to the visual alert “signal” – which has been in existence for at least 30 years but has not spread much beyond official documents. Google it.