Gaelic: hostility, continuity and recognition

In a lecture last week Education Secretary John Swinney said that ‘hostility to Gaelic has no place in Scotland’. He really meant ‘should have’ rather than ‘has’, because hostility to Gaelic still has a prominent place in Scotland, as it has for many centuries. Minority languages are ‘despised languages’, wrote the late sociolinguist Robert Cooper, and Gaelic speakers have experienced what Cooper called ‘the ideology of contempt’ at least since the late Middle Ages. Some of the expressions of hostility seen today would have been familiar a century or two ago, while other inflections are newer. Some contemporary critics of Gaelic seem frustrated with what they perceive as a pampered minority receiving special privileges; but until very recently it was obvious that there was no pampering, indeed hardly any provision or support at all.

One line of attack that has become prominent in recent years, particularly in the sometimes febrile environment that has developed in the context of the independence debate, is that Gaelic is being aggressively promoted by the SNP as part of a nationalist agenda. This interpretation fundamentally misunderstands the politics of the SNP and, more importantly, the history of Gaelic policy in recent decades.

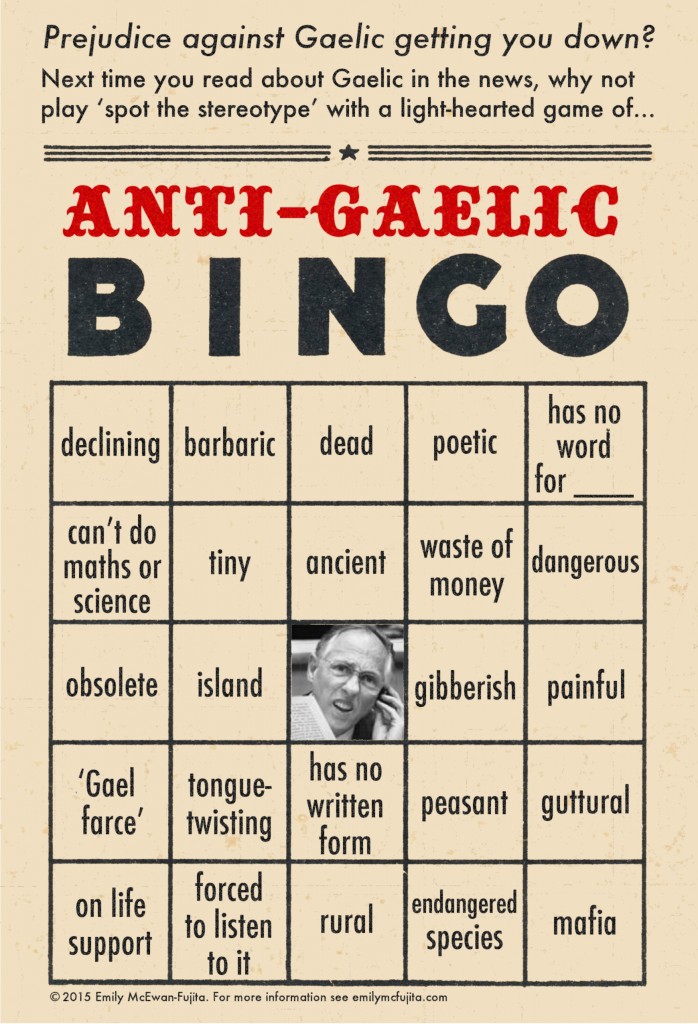

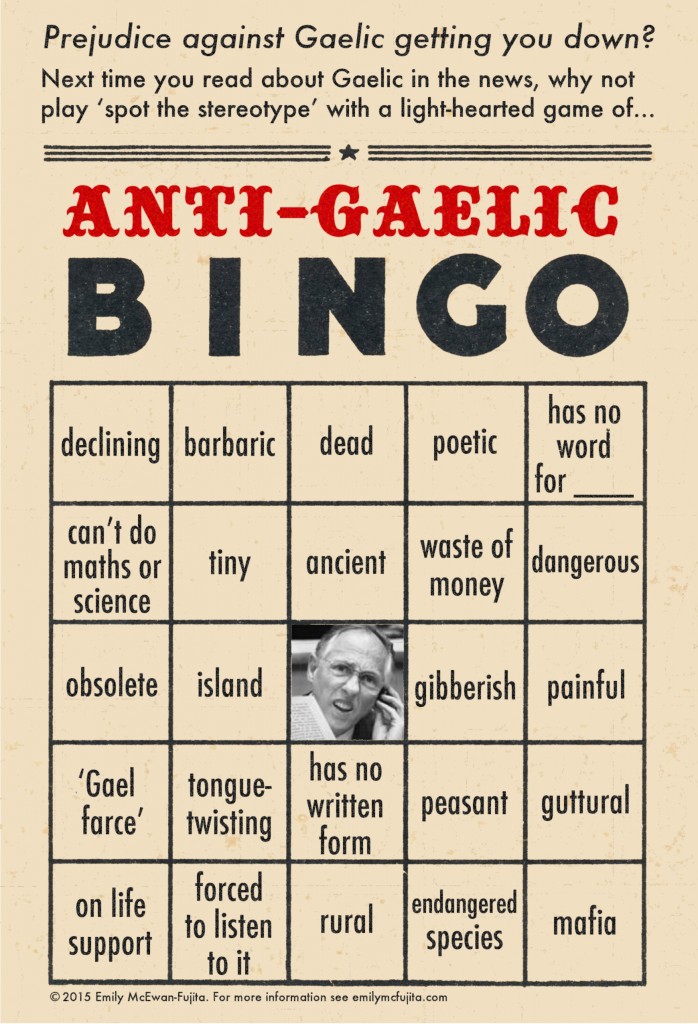

[Illustration copyright 2015 Emily McEwan-Fujita and Gaelic Revitalization.

Used with permission.]

To the small band of Scottish nationalists in the early 20th century, Gaelic was a prominent and important issue, and some even envisioned the ‘re-Gaelicisation’ of Scotland. But from its foundation in 1934 the Scottish National Party has never made Gaelic a priority, much in contrast to its sister party in Wales, Plaid Cymru, which has always placed a strong emphasis on promoting the Welsh language. As is the case with other political parties in Scotland, some in the SNP champion Gaelic, while others are indifferent or perhaps even hostile. It would be difficult to find any evidence of great sympathy or support on the part of First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, for example.

Since coming to power in 2007, the SNP has actually taken very few new measures in relation to Gaelic. In fact, there has been substantial continuity in relation to Gaelic policy ever since the Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government laid the foundations between 1985 and 1990 by building a language development infrastructure and funding Gaelic-medium education and Gaelic broadcasting. Subsequent governments, from New Labour pre-devolution to the Labour/Lib Dem coalitions of 1997-2007 and the SNP from 2007 on, have effectively just taken a series of logical incremental steps following the historic leap forward of 1985-90.

In recent years, there has been an unfortunate mismatch between the taking of policy decisions in relation to Gaelic and the visible effects of those decisions. Particularly as the mainstream English-language media rarely cover Gaelic issues with any seriousness, this misalignment has helped create the impression that important measures were taken by the SNP government rather than its predecessors. For example, many public bodies in Scotland have begun to make much greater provision for Gaelic in the last few years as they develop and implement Gaelic language plans pursuant to the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005. This Act was introduced by the Labour/Lib Dem coalition in 2004 and then passed unanimously by the Scottish Parliament in 2005; by no means is it a creature of the SNP.

Similarly, the Gaelic television service BBC ALBA was launched in 2008, after the SNP had taken control of Holyrood, but the decision to establish the service was taken back in 2005, following complex negotiations between Westminster, Holyrood and the BBC that had dragged on for a number of years. In turn the decision to establish a dedicated Gaelic channel built on the key decision taken by the Conservatives in 1989 to dramatically increase funding for Gaelic television.

On the education front, Gaelic-medium education has grown very considerably since the first units opened in 1985, but the principal funding mechanism, the ‘Specific Grants’ scheme established by the Conservatives in 1986, remains in place. Since the mid-1990s Gaelic campaigners have worked to establish free-standing Gaelic schools instead of units within English-medium schools. The first primary school was established in 1999 (in Glasgow), the first secondary in 2006 (also in Glasgow), and four more primaries between summer 2007 and spring 2016. The then Scottish Executive provided special capital funding to assist in the development of the first Glasgow schools, and the SNP government has developed this policy further by establishing a formal Gaelic Schools Capital Fund. There has been no significant change of policy in relation to Gaelic education more generally, however. Certainly there has been no push (and no campaign from Gaelic activists) to make Gaelic a mandatory element in the curriculum, as happened in Wales in the early 1990s.

“support for Gaelic, including Gaelic signage, has nothing to do with promoting symbolic difference vis-à-vis England but involves recognition, respect and providing meaningful support for Gaelic speakers and Gaelic communities to allow their language and culture to survive”

Bilingual Gaelic-English road signs have attracted particular controversy in recent years, but these began to appear in the 1970s and proliferated in the 1990s. Under existing policy (unchanged since 2007), any decision to install bilingual signs on trunk roads is taken on a road by road basis. The only such authorisation that has been made since 2007 involves the A9, but no signs have actually yet been erected on this road. Instead, all the bilingual signs that have appeared on trunk roads since 2007 (e.g. on the A83 and A85) were authorised by the previous Labour/Lib Dem coalition. So far bilingual road signs are confined to the Highlands, and 28 of Scotland’s 32 local authorities have none at all (besides the occasional ‘Fàilte gu . . .’ sign on the boundaries of towns or council areas).

As for the railway network, bilingual signs on station platforms (including those at Glasgow Queen Street, Scotland’s third-busiest station) first began to appear in the mid-1990s, and have become substantially more common since 2010, when First ScotRail extended bilingual signs throughout the network as part of a re-branding exercise.

One line of criticism has slightly more merit: the idea that bilingual signage sometimes involves a deliberate attempt to heighten the symbolic difference between Scotland and England. Large signs at border crossings such as the A68 at Carter Bar announce ‘Fàilte gu Alba’ below ‘Welcome to Scotland’. But this policy is actually based on a 2005 report commissioned by the Labour/Lib Dem government, First Impressions of Scotland, which recommended that ‘bilingual English and Gaelic signs should be used’ at international points of entry ‘to emphasise the sense of place’. And Scotland is not and never has been a monolingual place. English-only signage erases both the history and current reality of Gaelic in Scotland.

More generally, The limited measures taken by recent governments should be understood as minor steps to redress the damage done over the course of several centuries. It is unhelpful to turn Gaelic into a political football, especially if arguments and attacks are based on raw misinformation or tactical distortion.

‘Bilingualism’ when applied in the wider Scottish context implies and essentially advocates the ongoing suppression of the Scots language. How is that defensible on any level?

‘Squealin afore ye’re hurt!

A much more relevant question, given that the specific topic of the post is the SNP and language policy, is why the SNP has done so little for Scots since 2007. As with Scots, we see overwhelming continuity in policy pre- and post-2007. Language is just not an important issue to the SNP (or indeed to other political parties in Scotland).

as with *Gaelic*

Clive is absolutely right, the state suppression of Scots language is indefensible. It is also cultural discrimination.

There is no duty on anyone to mention the Scots English language when writing about the Scots Gaelic one.

That’s cheap (I’m sure some people who don’t like Gaelic see it as the Scots Irish language)

Can you give me the annual expenditure on gaelic in Scotland,plus the capital cost and maintaince of Sal Mhore.Then we can start making some objective observations on some of the issues you have raised.I have already approached senior figures at theCollege with this request and was treated as if even to ask such a question was blasphemous!

I got info from Highland Council abiut 3 years back. Cost per pupil of education in Gaelic was lower than cost per pupil in English. Main difference was that the Gaelic speaking school had more pupils than your average English speaking school in the Highlands.

Maybe Sabhol Mhor Ostaig were surprised that somebody would ask such a question without knowing how to spell Sabhol Mhor Ostaig? Well done for so succinctly confirming the anti-Gaelic bias at the very heart of Scottish society, and that includes the independence movement…

Excellent, myth-busting, illuminating piece from Wilson McLeod.

That’s just such a daft post.

Apart from the important arguments (the rights of Gaelic speakers, the intrinsic value of culture, the importance of Gaelic in the history, present and future of a Scotland that has never been monolingual)… we might easily ask what’s the current and projected future return on the investment of paying for Gaelic teaching, including Sabhol Mhor Ostaig.

It probably includes providing good jobs in broadcasting, publishing, teaching and research in the Highlands and Islands, which may not be necessarily easy to do otherwise, and which naturally feeds into, supports and sustains the whole communities in the shops, schools, and services they use. Paying for Gaelic probably supports multiple Scottish/UK government objectives.

It probably includes a significant current and future monetary return from tourists who want to visit places that are culturally interesting (It’s harsh on our cousins but I’ve always prioritised Europe or Latin America over Australia or the US in my travels, because they seem similar to us). In a world rapidly homogenising under globalisation, with literally thousands of minority languages expected to be lost this century to English, Spanish, and Arabic etc, the economic value of “interesting culture” is only going to increase.

It’s “just such a daft post” yet you manage to identify 3 important arguments in it?

You may ask what’s the current and projected future return on the investment. It’s fine to wonder where the money goes and why spending on Gaelic. And it’s interesting to question the comoditization of language and “interesting culture” – something that the British government has actually shamelessly been doing with the English language for far longer.

The problem is that you assume that all tax payers will hold the same view than yours. I don’t see “investment” in every pound I give to the government. To me, education, health and culture are not equities. The financial returns they provide – if they actually do – is only added value. I feel very uncomfortable with pricing everything and some people do.

I understand we’re living in a capitalist world where markets should be unregulated and where only the fittest should survive. But you know what? F*ck the fittest.

I think I agree with you Joe. (After posting I did recognise that my comment “just such a daft post” was unnecessarily hostile… and would have removed if edit-able)

It should be fine to wonder why money is spent on Gaelic, and where it goes, but then we live in an environment of ill-founded current and historical hostility to Gaelic. If we want to question the money…we should be honest enough (or canny enough) to consider the flip side in that cost/benefit analysis. (There will obviously be lots of real and non-financial elements in that analysis. For example, compared to other European countries we seem to be famous for not speaking other languages. People often say why teach Gaelic when you could teach Spanish or Chinese. To shift Scottish/British culture to care about learning languages, I would guess that valuing and teaching Gaelic, Welsh, Scots, Cornish etc. would benefit rather than detract from a cultural shift to learning more languages).

I’m not sure that “investment” has to imply financial returns and markets. I did frame my comment in financial terms to play devils advocate… and I do think that in the short-medium term we’ll “get back” more than we put in to Gaelic… but I agree there’s more to life than money and markets, and there’s a huge risk if you make that your argument that at some point the financial balance tips the other way! (The same is true for monetising “ecosystem services”… not long now and someone will be (short-)selling derivatives of the flooding prevention benefit of a woodland near you 🙂 ). Anyways… I think it’s okay to talk about investment in education, health, culture and communities if the return you seek is healthier, more-connected, happier people… I think we mibbe agree but would just use different words.

Nae worry, and apologies for the rude word – I’ve clicked the reply button too fast as well 😉 I’ve heard some many times that Gaelic was a waste of money, that it’s difficult to remain to polite.

Anyway, yes, studies indicate that supporting Gaelic provides beneficial returns in terms of healthier, more-connected, happier people. And GME students do learn foreign languages faster than their monolingual English speaking counterparts.

But isn’t there a danger in ‘selling’ these practical benefits – once they have reaped the fruit of learning Gaelic, GME school students and their parents may give up the language altogether, for instance.

Of course, everyone should be free to choose their language – though English is clearly imposed by default – but by focusing on the beneficial returns, aren’t we reducing the language to a mere mean?

Ha! I was expecting that abuse but I’m sticking to my point. I would suggest that one of the core reasons that gaelic is demonised is that it is often over sentimentalised and infantilised by its supporters and as a result not taken seriously by many in Scotland. I’m with Iain Noble ( sorry Sir Iain Noble we have to take these inherited titles seriously ) that a key part of the re-establishment of the integrity both economical and cultural of the highlands has to be the re-establishment of Gaelic, which is why I went to Sal-Mhore ( anyone with even the vaguest understanding of the diversity of that language should know that there are many variations in spelling ) to start to learn it. So any real progress can only be made by openly establishing and publicising costs, explaining what is being achieved and then making a cogent and sensible case for its further development. We have a valid product to sell, and if we are going to sell it let’s tell it as it is , loud and clear.

My apologies my remark starting anybody with the vaguest was unintentionally rude

Maxwell says:

“I would suggest that one of the core reasons that gaelic is demonised is that it is often over sentimentalised and infantilised by its supporters and as a result not taken seriously by many in Scotland.”

Ok, Maxwell, we get it. It’s the fault of Gaelic speakers that Gaelic was suppressed for centuries…

Blame the victim for being victimized, the oldest psychological fall back position in the book….

Quite right Mackswhel, smart.

A better question would surely be – can anybody estimate the annual expenditure on English language in Scotland?

The Yes campaign avoided Gaelic content I think so as not to be seen as too “ethnic.” The fish doesn’t see the water it swims in. English is also an ethnicity, a culture, a worldview.

But with simple fonts, basic colours and an absence of cultural markers othwr than the Saltire, a “neutral” campaign allowed others to project onto it their version of a future Scotland.

During the campaign, the only Gaelic bumper sticker I saw was for Better Together, in Cromarty (now there’s a linguistic faultline). I have since seen a couple of Bu Chòir stickers.

Until I read an article by Paul Kavanach aka “Wee Ginger Dug”, I had no idea how widespread the Gaelic language was used in Scotland. In future, as I travel round the country in my wee camper van, I’ll give a bit more thought to the names of the places I pass through or visit.

I’m a bit bemused by the anger and intolerance of some people regarding this subject. Surely, an increased level of knowledge about our history and culture should be welcomed.

This excellent article is most welcome. Clear, succinct and fact-based analysis.

Sabhal Mòr Ostaig!

I’ve long been puzzled by the Gaelic welcome, at Carter Bar, to a part of Scotland that has close to zero Gaelic speakers, so it’s good to see the explanation above – “ ‘bilingual English and Gaelic signs should be used’ at international points of entry ‘to emphasise the sense of place’. ”

Excellent, no problem. But I’d be even happier with tri-lingual signs – ‘Welcome ti Scotlan – safe in, safe oot!’ appropriately adjusted for locality.

There were 8 learner gaelic groups in the Scottish Borders when I learnt the language ten years ago. Many BORDERERS have went out there way to learn about their culture and place names such as Ancrum.Lusseddun. Archil dun(earlston)Melrose Innerleithen etc are cognate with the language. Tha gu gearbh gaidhlig seo

Oh aye laddie Cairter BAR(Bar bit means top or height) and further doon the road at bonjethart(bon or bun is reckoned to be the bottom bit.Bun gu bar frae the bottom to the top.Smashing eh gaelic golore fae gobs Wi nae gaelic

There’s some appeals to Scots language in this thread, but I’d ask whether its promoters would be prepared to do what Gaelic speakers have done and agree a standard, or “BBC Scots” that is countrywide.

That’s what Gaelic has done, notwithout grumbles, but it is the gateway to official recognition.

Italian, German etc. have all come about in the same way, from the same agreement on a standard form.

Spot on! Ower mony fowk prefer dae-it-yersel Scots – their ain personal Knockando! Hugh MacDiarmid’s Scottish Renaissance happened in a far awa countra o which oo ken little.

Whaur is wir Scots Language (Scotland) Act? Scots leid is wir Scots cultur. Mair Scots fowk wid vote Yes if thay felt mair Scottish. Duh!

This article is aboot Gaelic, Alf.

Destroy the language, destroy the people. That is what colonialists do. And how many of us remember how disparaged on was if they spoke with a Scots dialect. Gaidhlig or Scots, they have both been discrimated against. That I think is exactly Alf’s point Graeme.

Willie is right, Graeme. Research tells us that language IS our culture – the way we think and do things. That the state steadfastly refuses to teach Scots bairns an aw fowk thair ane langage shuid tell us all we need to know. Cultural suppression is self evident and with the clear intent to force Scots to feel more British rather than Scottish, to readily experience that cultural cringe crawl up wir spines whenever fowk hiv the cheek tae rant in braid Scots, and to make our very nation appear less viable or even desirable as an entity. The Yes/No 2014 referendum was essentially a cultural decision, not an economic one. It mattered little the currency, No voters were already culturally programmed.

After the discussion on Radio Scotland about Gaelic, I too paid more attention to Gaelic place names wherever I went and was happy and surprised to see many, including house names on a visit to the East Neuk of Fife. Incidentally and possibly quite unrelated to this, I also noticed many Saltires and EU flags displayed in the same area after the referendum!

There is an educational advantage to learning a second language before the age of 8 which is that this changes something in the brain which makes it easier to learn other languages later in life. A friend of mine who grew up in a multi-lingual family (Italian, German and English) is now fluent in English, German, Italian, French, Arabic and Russian.

This could be a great advantage if we are to be an independent (from the UK) nation trading globally.

This is an excellent article, long overdue, and hesitate to return to quantifying and monetarising gaelic for many of the reasons already defined. not the least being that there are so few figures ri work from. So let me be the gael and tell it in a story. in the early 1990s I interviewed Iain Noble for the Scotsman and asked him to comment on the theory that the decline in gaelic had now reached such a level that it couldn’t be brought back as a living language and he replied ” If you visit a dying man you dont tell him he’s dying you tell him to keep fighting, miracles happen.”

Noble was acknowledging that the game was nearly over and that miracles were needed, So we have had miracles, Sabhal Mor, the Feisd, broadcasting. But they havent been enough. Now you have to look at the figures. Lets make one up £60 million since that interview? And how many gaelic speakers? 60,000? We are losing the game, it hasn’t worked.

I would suggest that we need to look at new ways and that they should concentrate on energising gaelic speaking communities through investment in their industries- for example getting the Ard-mhor connector funded and not making such a mess of ensuring that funds from green energy go into communities and not entrepreneurs. Not that I wish to be irritating, perish the thought

“…hostility to Gaelic still has a prominent place in Scotland, as it has for many centuries.”

This ongoing discrimination applies also to the Scots language, as the absence of any Act confirms.

The death of any language is one of the saddest event mankind can suffer, for language is a vibrant living entity.

wholeheartedly agree.

Also, I think the concept of ‘language death’ is a meme that people often absorb and repeat uncritically. (In my Gaelic language class our teacher asked us a the beginning “why do you want to learn Gaelic?” – to which someone innocently replied: “I’m interested in dead languages”!). It seems like deaths are often pronounced too early, by people who don’t speak the language, which if anything has the effect of hastening the death. If it has speakers who use it to communicate and use it in creative ways, and pass it on to their children, then it cant really be dead.

I read a good short story once in which it said every human has three deaths:

The first is when your body stops functioning.

The second is when the last person who knew you dies themselves.

The third is when your name is last read or uttered by the living.

Cait a bheill e

Just one point though. I value the Gaelic language and agree it deserves support. But I think there’s a huge risk of manufacturing an identity and giving the impression that Gaelic culture existed in areas it never has or that it is THE indigenous culture of the whole os Scotland. An example of this would be the use of Gaelic signs as you cross the border into Scotland. Yet historically it is more likely that these areas were using a brythonic tongue followed by a combination of later Norse influence and AngloSaxon Northumbrian culture followed by Norman culture. Similarly in Central North Eastern areas thought of as traditionally Pictish prior to the incoming of the Scots who then forced their own culture onto the P Celtic inhabitants, why should the impression be given that Gaelic is any more indigenous than later Scots English? Why not make the effort to use Bilingual signs in the typically original tongue of the area? So for example Norse may be more appropriate in some areas as a traditional version of an English placename, Brythonnic in others and Gaelic in those areas where it is appropriate? Isn’t enforcing and brainwashing a manufactured homogenous Gaelic identity onto the whole of Scotland (presumably with the agenda of creating a distinction from the nearby identical inhabitants South of the border) just as dangerous and ethically wrong as the past destruction and devaluing of Gaelic in those areas where it was long spoken?