The Old Flamingo Ballroom

You won’t be able to read this article. The whole country’s ‘going gaelic’. It will be compulsory next. Of course it won’t really but it’s the sort of cultural of panic that is the tone set by a lead commentary column in this weekend’s Guardian (‘Why I’m Saddened‘). It’s reminiscent of the now widespread xenophobia gushing daily from the gutter press.

As Alasdair Mac Gill-eain said previously on Bella C:

“Most Gaels are wearily tholed to the almost vituperative outpourings of the Daily Mail against state support for Gaelic: they couldn’t sell their tabloids any other way.”

Now it seems the Guardian’s own Uncle Tom, Ian Jack is at it as well.

Poor old Ian is upset. He’s got his passport and it’s got the cheek to refer in passing to some of the other cultures that make up this Great Country of Ours. I wonder where he’ll go with his passport? I hope somewhere where they speak English.

In an article exposing an unimaginable lack of cultural self-awareness he writes an extraordinary sentence, this is it: “The Welsh and Gaelic phrases on the passport are surprising. They don’t answer to this present Britain. They exist in a more historical landscape, to redress old rural grievances rather than to express new metropolitan demands.”

Pause and reflect on the wonders of that sentence.

Deconstructed we have four key messages: You must answer to this present Britain. To be rural is to be grievous. Come and live in the city and shut up about your culture. Speak English goddamn you!

It’s difficult to know whether to think that the estimated 750,000 Welsh speakers in Wales should be more insulted by that or the 1.5 million people that can understand Welsh, or the gaelic speaker old and new, rural and urban? Is it more insulting to his own culture and heritage or that he feels able to consign another nations to ‘historical landscape’, itself a telling term.

He then has a predictable old moan about gaelic funding rolling out the old canards about state funding which, when boiled down amount to: “how dare they undo the linguistic ethnic cleansing we’ve achieved?”

As Wilson McLeod has laid out previously : “The current budget for BBC Alba is only around £20 million per year (with just £14 million for content), compared to £103 million for S4C (the Welsh public broadcast channel), £89.5 million for BBC 3 and £1,200 million for BBC 1.” So gaelic has less than a quarter of the BBC3 budget. Or to put it another way, Jonathan Ross was paid more than it costs for gaelic content.

But Jack is not interested in facts or true reflection, it’s just an exercise in paying someone for maudlin out loud: “All the Celtic languages are a mystery. How far would I need to reach back to discover an ancestor who spoke Gaelic? Perhaps to what in England would be called the Chaucerian era, perhaps to never.”

It never crosses his mind that it might not actually be about him.

He has made a hallmark of looking backwards (but not too far back). About 1957 seems to be the EXACT point when everything was right in Britain. His truly execrable The Country Formerly Known as Great Britain (2009) is a whole book dedicated to this genre of looking backwards and boring people about trains.

Elsewhere he mumbles: “Is Scotland so very different from England? More and more of its manmade landscape looks much the same: slip roads uncoil themselves expansively from motorways, property developers’ flags flutter above new private housing estates built of pastel brick, old shopping streets look ghostly, road-signs point the way to superstores.”

Jack plays cultural arithmetic taking the number of gaelic speakers in Scotland then: “Multiply that figure by five to get the number of Cantonese speakers in the UK, by 10 to reach Punjabi, by 20 to those who use Bengali, Urdu and Sylheti.” To what end is this exercise?

History is clearly his obsession but not his subject. He writes: “By 1755, Gaelic speakers numbered only 23% of the Scottish population.” How did that happen? That seems an odd date. Did anything happen around that time that might have precipitated its decline? We’ll never know because Jack hasn’t told us.

Jack is a nominally Scottish writer who – like many – is detached from his own history and this displacement generates a sort of self-loathing. He doesn’t mention the failure of the Jacobite Rebellion (1745–6) and the subsequent suppression of the Gaelic language and culture of those who had supported it. Nor does he seem aware of the ‘mass migration’ from the Gaelic Highlands in the 18th and 19th C. Instead, forlorn and self-comforting he writes:

“What I remember of Cardonald is the old Flamingo ballroom and council estates that were well thought of.”

A few months ago Jack was interviewed by the Scottish Review of Books and the author and his interviewer wrapped themselves in a warm blanket of unionism and snuggled down for an evening of nostalgic revelry.

Jack’s prejudice ignorance should be challenged and some facts put in the public realm or tbis impostition of the anglosphere will corrupt our own self-knowledge: Cuimhnichibh air na daoine bho ‘n d’thainig sibh (Remember the people whom you come from).

As a professional trilingual linguist, Welsh (mother tongue), French and a patois currently spoken by some non-descript people around me here in Bedfordshire, I heartily endorse all your comments, Mike. It’s far too late to go into full rant and anti-Jack mode, although I trust all good Celts – Gaels and Brythons – will apply their fingers to keyboards to demonstrate their disgust at his piece.

But, I leave you with this parting idea. This article appeared in the same week that my first language became official de jure in Wales. It is clear from studying the appropriate statutes, that this other language which is supposedly the common linguistic thread that unites the inhabitants of these islands, has NO official status de jure therein. I would advise Mr Jack, in the same way as you have done, Mike, to sojourn on his new multilingual passport on a desert island where he can run up the flag of the Disunited Kingdumb (but not mine) at any time he wishes, and converse – with himself, naturally – in the vernacular he feels most at home with.

Yours, as ever in the spirit of Cymro-Scottish cooperation – linguistically, politically and socially – Welsh Sion.

Andrew Davies, in his monumental history, “The Isles” shows clearly the roots of these attitudes. The original inhabitants of the isles, their culture and their language had to be marginalised and ridiculed, with the aid of the Roman myth, to sanitise the Germanic and other continental invaders and the monarchies that evolved from them.

I am not a Gael, and I don’t have the Gaelic, but I happily support any initiatives to protect this endangered language in all its forms and variations. It is part of our culture and our heritage – it is an endangered species, a living language, spoken by a minority, but a vital part of what it is to be Scottish – and Welsh and Irish.

As for Ian Jack’s Uncle Tomism – well, I regret it, because at his best, he is a fine writer, and deeply Scottish, despite his protective colouration. I understand his behaviour – it is characteristic of many Scots who have lived and worked in England. It is a kind of desperation to assimilate, to blend, but the harsh fact is that English people privately despise Scots who behave in this way, and regard it as the flip side of the coin of being aggressively and noisily Scottish and showing contempt for English values and culture.

I lived and worked very happily in England for a total of ten years of my life, and I never felt the need to behave in this way, and I believe that I was respected for my Scottishness as I respected my English friends, neighbours and colleagues for their Englishness. Canadians and Americans have often commented to me about how baffled they are by this behaviour by some Scots, and their contempt for it is equally evident.

My apologies for two crass inaccuracies in my previous comment, which I am indebted to Sion Rees Williams for gently and courteously bringing to my attention.

Firstly, the author of the Isles is of course Norman Davies (a Welshman), not Andrew.

Secondly, the Welsh language is not Gaelic (Q-Celtic), but Brythonic/Brittonic (P Celtic). I have offered my apologies to Sion by email.

EMAIL to Sion Rees Williams

Sion,

My sincere apologies for my sloppiness and inaccuracies, which I will

correct as best I can on bellacaledonia. I can’t believe I made them,

since I am currently reading Norman Davies wonderful work for the

second time. (I carry it now as an ebook on my Kindle.)

I have probably upset my Gaelic countrymen and my Irish Galic cousins

as well, and my apologies to them as well.

best wishes,

Peter Curran

Thank you Peter for your gracious response. I had no cause to rebuke you publicly and may I wish you all the best in your endeavours. Thank you also for letting me be privy to your thoughts on other matters.

The Scots are enhanced as a nation by the fact that some people speak Gaelic, just as we in Wales are enhanced by the continued existence of Welsh as a living language. To deny this is to deny one’s nationality, which is what Ian Jack seems to do!

Of course, as EVERYBODY knows, and Ian Jack would confirm, the inhabitants of southern Britain spoke English amongst themselves until the anglo-saxons arrived, and then they all turned to Brythonic, just to annoy the visitors! I’m sure it was the same in Scotland with Gaelic!

Whit a canna unnerstaun is in a hail article anent the linguistic situation in Scotland yes dinnae mention Scots at aw. Ian Jack wis sayin that Scotland haes a multi-lingual tradeetion, it’s no jist Gaelic vs English, ye ken.

Good point, except the article is about a piece of writing about Gaelic. It’s not about 100%, it’s about respect for culture and knowledge of how a language was systematically undermined as part of an official policy.

Naw, it’s no’ – ye’re right Geordie. But whit version o’ Scots tae teach? Broad Glesca, ur the Doric or a’ the ither dialect variations. It gies me a sair heid tae thin aboot it! Gonnae gies uz a brek … It’s bad enough Ah cannae speak Gaelic, but dae Ah huv tae go back tae adult education classes to learn tae speak like a north easterner? But it diz occur tae me that Glesca folk mibbee lost a heeluva loat o’ words ower the years – and efter a’, Strathclyde wiz a Welsh kingdom, wiz it no’ ?

Good comment from Wee Geordie. Scotland was never 100% Gaelic the way Wales was 100% Welsh. But those who did not speak Gaelic spoke Scots and that distinguished them from the English. Apart from vowel substitutions plenty of Scots words are still in common use and some have no exact English equivalent. The English have adopted some eg scunner. But for how much longer will they survive? Without turning into Harry Lauders we should be making an effort to promote the Scots lexicography. I am already encountering comprehension problems with my Welsh relatives.

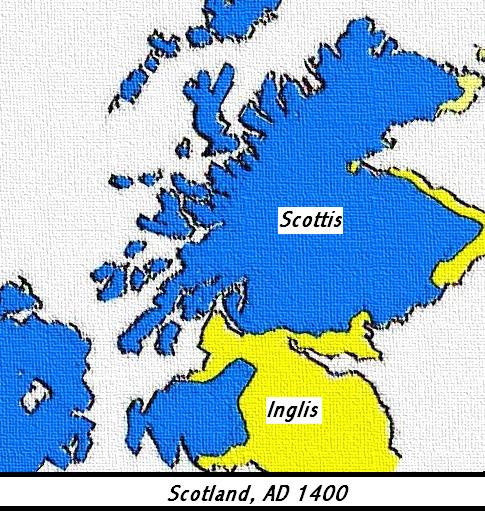

Doonhamer – is there any evidence that those historically who didn’t speak English spoke ‘Scots’? What about Norn in the Northern Isles? And wasn’t ‘Scots’ actually ‘Inglis’ and brought here by the ‘English’? While ‘Scots English’ may or may not have diverged from its Northumbrian Anglo-Saxon roots, is there any difference today? Where is the line between ‘Scots’ and ‘Scottish English’? I would argue that its all the same today as very few of us actually speak standard English anyway.

I’d agree with Peter Curran above about what ‘version’ of ‘Scots’ is ‘standard’? Maybe Doric and Glaswegian, Eastern ‘Scots’ are actually all separate dialects of Anglo-Saxon? Numbers are a case in point, is ‘wan’, ‘yin’ or ‘ane’?

Whatever, I don’t see ‘Scots English’ as being under threat. Gaelic is and therefore we should not only protect it and develop it but allow those of us who do speak it to use in as many domains as possible. Something denied to us for centuries and that lead to its decline.

I agree with Mike’s comments; I found Ian Jack’s article to be obnoxious, extremely tendentious, pathetically argued, and ultimately resting on the idea that what I feels about Gaelic is appropriate for the rest of us.

A glorified pub rant is how it struck me, well below normal standards surely ……talking of the pub, the only positive thing you can say about the article was that Kenneth MacKenna didn’t write it, another Guardian journalist who contrives ever new ways of trashing his country for money on a weekly basis.

Obviously the Geneva Conventions, which specifically state the right to speak one’s own language in public places as a fundamental human right, or the European Charter for Minority and Regional Languages (and all this entails in terms of funding and the public presence of Gaelic) are not good enough for Ian….

By the way, Ian Jack mentions another article, by Kenneth Roy, in the Scottish Review which I’m sure many will have seen. Roy questioned the money being spent on BBC Alba, again doing some superficial numbers and coming with the conclusions that a Gaelic conspiracy is afoot in Scotland, (or BBC Scotland) . Roy declared himself to be in favour of supporting Gaelic, but obviously not spending serious money on it…tis despite BBC Alba being clearly far more representative of Scotland than BBC Scotland is….which is surely the point of a channel which goes by that name.

Then there was also that journalist whose name I can’t remember in The Herland who Alisdair Mac Gill-Eain picked up on; again there was a reference to a train station, and somehow the presence of this “foreign” language being a personal insult.

Apart from the obvious conclusion that journalists make up their stories as they wait for the train in the morning, what else can be drawn from all of this? I woudl say:

1) There is a near-total invisibility of Gaels, or people sympathetic to Gaelic, writing in the mainstream media and the argument for putting money into Gaelic needs to be put forward better. It’s not just about “the Gaels” (I don’t quite know what that means), 1745, the Clearances etc, though it is that too. But defending Gaelic or Scots is synonymous with defending Scottish culture per se, and therefore human culture per se. If Gaelic or Scots were lost – and they are in real danger – it would constitute the biggest national disaster since Darien in my opinion.

2) There is deep seated ignorance in Scotland, amongst people who should know better, about second languages learning in general , about what it gives people, how it opens their minds to a wider view of human existence and understanding of reality. Anybody who knows a second language simply knows this to be true. In a nutshell, if more people in Scotland spoke French, then more would speak Gaelic too. The problem is that the public perception is that all languages say the same thing and of course this is simply not the case.

3) Backing Gaelic is perceived by many people as a threat to the status quo and the cultural and historical reality of Scotland. For example, Ian Jack seemed to think that giving Cardonald its Gaelic name could only be an attempt to say something about its past. Most places in Scotland were probably Gaelic speaking in the past, but the signs are there to take Gaelic and Gaelic speakers seriously, as equals, not make some claim about the past. Or is anybody arguing that Queen Street Station was once a “Gaelic speaking railway station”…?

It is ludicrous misunderstanding of what Gaelic place-names are for. But I’m not sure the argument is put like that often enough, by which I mean, about the present, not the past, about language and culture, as opposed to history and “the real Scotland”, something which we are never going to get agreement on.

MacNaughton’s para 2) commencing “There is a deep-seated ignorance …” captures a fundamental point about the reasons for learning a second language, one that strikes home deeply to me, and I hope will have the same impact on others.