Who won the Election?

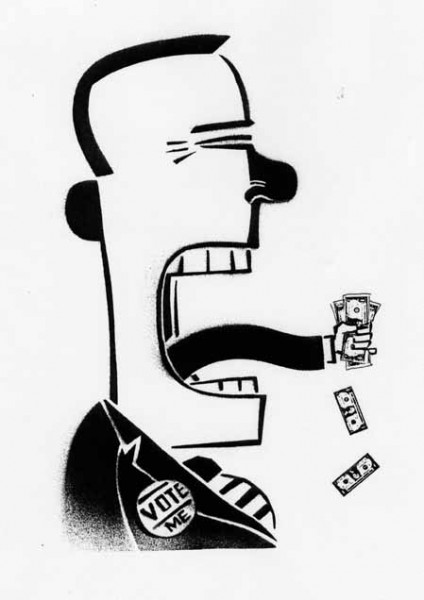

Nicola Sturgeon? David Cameron? Think again! The financial elite won this election; or rather, the system the financial elite works in and for. The blind faith that given time, patience and a hefty dose of ’fiscal responsibility’ the financial system can recover and all will be well – that faith has gone unchallenged. Although it caused the crisis, the financial system is still considered the means of resolving it. Reform of finance – all the rage in the immediate aftermath of 2008 – has all but disappeared from the political agenda. The need to anticipate and accommodate to the demands of the financial elite remains the litmus test of a viable economic policy.

Instead of a critical debate over the already discredited economics of ’austerity’ the election degenerated into hair-splitting over how fast to reduce the budget deficit. Since Governments actually exercise little control over their budget deficit, this became a vacuous controversy over posture rather than substance.

The Tories abandoned austerity economics years ago, but could admit it without abandoning their spurious claim to ‘sound’ economic management – and giving Labour license to spend. Austerity economics also served the Tories well as their excuse for dismantling the welfare state and privatising health services. Instead of attacking austerity, the Labour Party chose to compete on the same ground. In its futile efforts to outflank the Tories (from the right!) Labour pledged to reduce the deficit every year. Their pathetic failure to accept a progressive alliance with the SNP may well have sealed their fate.

David Cameron attacked the SNP as though it was the devil incarnate. Yet its proposal to stimulate the economy was so modest it would have less impact on the deficit than the Coalition’s failure to meet its own targets. The SNP accepted the case for ‘fiscal responsibility’ and proposed to reduce the deficit only a bit more slowly than Labour. The differences between the parties were not over economic fundamentals, but over the associated issues of timing, impact and distribution. With the Tories helping the rich to help themselves, Labour hoped their fetish of ’working families’ would appeal to a disenchanted electorate. But vague promises – even erected in stone – had little purchase given Labour’s own commitment to austerity, including even a cap on welfare spending.

The aim of reducing debt by eliminating the deficit suffers from at least two misconceptions. First, public debt run up to save the financial system from itself is not a threat to stability, so long as the debt is financed by domestic savings and not by borrowing from abroad. It is the extent of external debt that matters. Second, measures to reduce debt during a recession also tend to reduce economic activity, thereby exacerbating the very problem they are meant to address.

The SNP kindled a ray of hope by proposing modest growth instead of further cuts. And they brought a bit of decency to British politics by challenging the punitive targeting of the unemployed, the sick and the disabled. In doing so, they helped to resurrect ‘social democracy’ as a progressive value – no mean feat in today’s ‘neoliberal’ world. But in terms of fiscal policy, there was little to choose between the parties.

No party put financial reform at the heart of its agenda. On banking, the Tories offered more of the same: more competition on the High Street, ’tougher’ regulation in the City, privatisation of the publicly owned banks. They proposed only to ‘ring-fence’ – not separate – investment banking from commercial banking, but not before 2019. Labour too promised to foster competition by limiting the market share of the big banks and encouraging ‘Challenger’ banks.

Labour did propose a British Investment Bank, while the SNP emphasised the role of the Scottish Investment Bank. State banks may indeed improve investment funding, but they can do little to make finance as a whole work more effectively for the economy. Without significant financial reform, there is no prospect of a sustainable recovery. Without such a recovery, the economy will continue to suffer from low investment, low productivity, and falling real wages.

Meanwhile, Rome – or rather, Athens – burns. Economists like Joseph Stieglitz puzzled over the hegemonic grip of ‘austerity economics’ in the UK (not to mention Europe) need only look at what is happening in Greece. The Greeks elected a Government to end austerity, but they are deeply indebted to international institutions determined to re-impose it. As their Government runs out of cash for pensions and pay, and either accepts the unacceptable or faces expulsion from the Euro, the difficulties and dangers of excessive borrowing seem ever more perilous. And the UK economy, severely unbalanced by the role of the City, is especially vulnerable to market fluctuations. The UK’s external debt – almost entirely held by the financial sector – is estimated at over four times GDP. It did not need the SNP’s progressive rhetoric of the SNP to panic voters into opting for the apparent security of austerity economics.

Nor are voters in Scotland somehow impervious to insecurity, regardless of the basic soundness of the Scottish economy. The absurdities of our electoral system should not disguise the reality that opinion in Scotland remains divided. Progressive politics requires not just on good intentions but a credible agenda. The YES campaign might have won last year – despite the media bias, the Vow and the dirty tricks – had there been a convincing alternative to the scare-mongering of Project Fear about the financial risks of separation. The role of finance will remain a critical factor in any future referendum. The prospects for independence will remain doubtful so long as the fundamental issues of finance (such as the currency) are not resolved.

Faith in recovery through the financial market is misplaced. The financial elite does not know which way to turn. It merely wishes for a return of the good times, when confidence was high and greed was glossed as a way of galvanising growth.

The New Economics Foundation (NEF) offers an agenda for financial reform. Breaking up the big banks would be a first step. Dominated by the City, the UK banking sector is highly concentrated in four ‘too big to fail’ banks. In Germany, two in three banks are local; in the US, one in three; in Britain, one in thirty-three. Local banks can focus on lending to small enterprises; support better staff-customer ratios, and promote financial inclusion. Instead of privatising RBS, it could be restructured into a network of local banks, mandated to serve the public interest, and supervised by citizen stakeholders.

As well as more mutuals, community and stakeholder banks and peer-to-peer lending, the NEF calls for a fully fledged State Investment Bank, legislation to establish transparency in investment, and curbs on speculation through the EU Financial Transaction Tax. This tax could also be introduced unilaterally without deterring genuine investment but only the speculative trade in financial assets. This is a ‘flight of capital’ much to be desired.

These reforms would bring the UK more into line with other countries. But that implies they would not go far enough.

A more fundamental reform is mooted by the NEF: that of the monetary system. In the UK, 97% of money is created by private banks – not by lending savings already deposited, but by crediting customers with higher deposits when giving them loans. That higher deposit might cover, say, the cost of your mortgage. This process has fuelled a debt-laden economy, in which the banks through lending both receive interest and inflate the price of assets (like housing). That suits them. The rest of us have to run harder, just to stand still. Over the past four decades, money (and debt) in the UK has been created at an average of 11.5% a year. When the system totters, the response is to sustain it by still more debt.

The Government meantime tries to influence the money supply by adjusting interest rates, but low-interest rates have failed to stimulate lending to business during the recession. Spiralling debt combined with low investment: no wonder Mervyn King said that ‘of all the many ways of organising banking, the worst is the one we have today.’ Today does mean ‘today’ for only a few decades ago, the state had a much more active role in controlling the money supply. The NEF suggests a return to greater controls, or even entirely removing the power of private banks to create money.

Iceland is contemplating just such a reform. In Iceland, the commercial banks expanded the money supply nineteen fold in the 14 years preceding the crisis in 2008 – contributing to hyperinflation, devaluation, high interest rates, asset inflation and growing debt. All this lending was ultimately guaranteed by the state. With deposits guaranteed, the banks competed for custom by offering absurdly high interest rates rather than through sound investment.

Iceland is considering a ‘Sovereign Money’ system, in which only the Central Bank (owned by the state) can create money. Money would be circulated by the state through a mix of spending, tax reductions, debt repayments or perhaps even a citizen dividend. The money supply would be geared to the overall pace of economic growth rather than tied to the speculative pursuit of trading profits by the private banks. The Central Bank would house all transaction accounts, interest-free and used for payments, not investment; it would fund the private banks which would offer interest-bearing investment accounts with different risks and rewards on maturity. This would restore some sanity to the financial system. But not enough.

In money markets, the focus is on purchase for resale of financial assets in various guises – securities, shares, bonds, currencies, derivatives. The emphasis has shifted from money being used to make things to things being used to make money. In place of investment in real economic assets (e.g. houses, businesses) we have speculative trading which drives the debt-driven bubbles – and collapses – in market values. And nothing much has changed post-2008. In the USA, for example, speculation in mortgage-backed securities – now packaged as ’collateralised mortgage obligations’ – increased 20% in the early months of 2011; meanwhile loans to firms were forecast to increase by only 1% in 2012.

Two Italian economists, Amato and Fantacci, ask whether we need money markets at all. And their answer is an emphatic NO.

They argue that money – both as a measure of value and a means of creating value through investment – becomes corrupted when it is traded as if a commodity in its own right. When money rules, everything – labour, resources, community, environment – becomes commercialised. The effects are perverse: favouring competition over cooperation, commodities over communities, efficiency over efficacy, money-making over merit.

The relation between creditor and debtor is unequal, for the former (e.g. Germany) can choose whether or not to extend credit; while in order to meet the interest on accumulating debts, the debtor (e.g. Greece) is usually dependent on receiving loans. Trade in interest-bearing debts favours the rich, who end up owning most assets, while enjoying the lowest interest rates. Poorer people and poorer countries end up with more debt, for which their creditors exact a higher and higher price. The profligacy of lending to poor risks is forgotten; when confidence collapses, those pressed into accepting loans are chastised as bad debtors, and forced to borrow at exorbitant rates. Meantime those profligate creditors are immunised from risk through the protection afforded by the central banks. Profit is privatised while the attendant losses are socialised.

Even in its own terms, though, the system fails to deliver the goods.

The more trading in financial products is dissociated from real economic activity, the more the financial market is subject to short-term speculation and shifting moods. The market operates like a Ponzi scheme, its fairy-tale expansion continuing only so long as no one takes heed of the wolf at the door, even when it cries ‘foul’. Excessive confidence fuels speculation for quick returns, but when confidence collapses the cash suddenly disappears. Then the means of restoring or sustaining its expansion – more borrowing – increases the likelihood of an even worse collapse.

Pumping money into the system (quantitative easing) does not work, if that money is not circulated. Circulation depends less on the value of specific investments than a generalised faith in a nebulous and essentially unpredictable future. Lacking this faith, money is hoarded – in 2011 most of the £1000 billion euros the European Central Bank (ECB) lent to the banks was immediately redeposited in the ECB. Or it is lent again at higher interest rates – European banks acquired loans at 1% and sold them on to the Portuguese government at 17%. Or used to speculate in land or raw materials, so inflating prices. Or spent on purchasing bonds with short-term high risk yields – in April 2014 speculation in junk bonds was running at nine times that of the comparable period in 2008. All this, while the real economy is starved for cash.

The core of this critique is the disconnection between credit and debt, when finance becomes a commodity to be packaged and exchanged in the market. So long as the system expands, the payment of debts can be endlessly deferred, regardless of risk. When confidence is excessive, speculation in financial assets displaces investment in real activity; when confidence collapses, investment dries up and the costs of austerity are displaced on to the wider society.

We can rescue finance from this fate, and restore it to its proper function. Finance is integral to funding economic activity, but only when there is an clear-cut relation between creditor and debtor, such that credits are spent and debts are cleared. Inspired by Keynes, Amato and Fantacci propose the creation of ‘clearing unions’ at local, national and international level. In a clearing union, a cooperative relationship between creditors and debtors is regulated (through fees, penalties and incentives) so that debts are cleared within a specified time-frame, restoring equilibrium. Once a debt is cleared, the credit extended also disappears.

Amato and Fantacci review the roots and development of the present financial system, emphasising its contingent and reversible character. There are alternatives. An International Clearing Union with its own international currency was proposed by Keynes in 1944; instead the dollar doubles as an international currency, subject to endless speculation and spiralling imbalances between creditor and debtor countries. The European Payments Union acted as a Clearing House for most of the 1950s, facilitating an unprecedented expansion in trade. Now the Eurozone, lacking any means of balancing credit and debt, is afflicted by austerity economics and a contagious sovereign debt crisis which threatens its survival. In contrast, there are many promising experiments in local currencies, geared to sustaining and expanding trade and economic activity at the local level.

Financial reform is not only possible, it is critical to the prospects for both progressive politics and sustainable recovery. The Labour Party shows the sad fate awaiting those who instead accommodate to the self-serving dictates of finance.

Amato, Massimo & Fantacci, Luca. Saving the Market from Capitalism: Ideas for an Alternative Finance. Polity Press 2014.

Amato, Massimo & Fantacci, Luca. The End of Finance. Polity Press 2011.

Fascinating article. Long and complex but definitely worth a read. Thank you.

I will share this on Facebook.

Thanks for that.

Horrible type face, insufficient line-spacing, and at 15-16 words to a line, very difficult to read. Like fighting your way through black porridge.

Can we please have better typography? 10-12 words per line is ideal for reading comfort, or the eye tires. The human eye has a span it is comfortable with, moving from left to right. This isn’t it.

And at least 1 and 1/2 line spacing.

There are fewer comments and people reading this horrible new layout. Can we please go back to the old website? The graphic design was far superior. Sorry to keep moaning about this Mike. I’m saying this as a great fan of Bella. It’s not helping the great writing this site provides, it’s impeding it.

MBC, what are you on about? The average line length is around 10-12 words on my pad, maybe you need to invest in a new one.

I have to agree. tiring to read and 15-16 words per line. I’m using a 27″ screen but the line length only reduces if I shrink the whole window to sliver.

I found it hard to read the above article and gave up a third of the way in, sorry. I’ll give the new look time to bed in to make sure its not just bias against the new, but this design is not drawing me in. What about a thread for comments on the new look?

Having said all that; huge fan of Bell and all your hard work. You have been a beacon of good information & inspiration in these times.

Can you send me a screenshot? I’ve looked across a variety of devices, platforms and browsers and cant see anything like you describe? We’ll look into it

I can’t see any possibility of financial reform for the foreseeable future especially with a Tory majority now encamped at Downing Street. What we have at present is communism for the rich & raw capitalism for the rest of us. Public monies used to bailout private corporations is a national scandal. Criminal in fact. Other than the problem of the rich controlling the corporate media we also have the problem of an ancient ruling class of aristocratic landowners who control vast amounts of the nations assets ( ie in land etc). But that is another story. Bailing out the banks is like giving heroin to a junkie. They believe the shakes of withdrawal are bad ( as in when the financial system begins to collapse) but is in fact the body regulating itself towards a purer state- we should have let the banks go into withdrawal in order to purge the debt burdened system from its speculative addictions. We also need to get people away from simplistic notions of shopkeeping & household finances as somehow analogous with servicing s vast modern national economy. This is an incredibly bogus analogy regularly regurgitated by the right wing media- its disingenuous but it is also very damaging as a ploy for limiting economic-political discourse. Labour had their chance to enact some sort of sensible governance upon the CIty that would have prejudiced long-term design over the destructive short-termism of the present ‘light-touch-regulation’. They also had their chance to overturn anti-union laws & did heehaw about that either. In such a hyper-financialized economy as the UK’s our politicians are nothing more than a managerial class obedient to the diktats of their market masters. We need to look beyond the politicians. We need a real sustainable grassroots movement that can build from the bottom up- rather than the present dictatorial authoritarian top down model that prevails in Britain- & by generating authentic community relations via activism we can make people ‘immune’ to the propagandist toxicity of the corporate media.

Totally agree. How? I throw the question out there to anyone who is successfully running such a grassroots organisation because I think all progressives need to start sharing what works, so that others have got templates that they can adapt to their region, town, or even street. And what about a central database of these inspiring examples that all of us can refer to? I think there are millions who want to do exactly what you suggest: ignore this miserable, lying government of the 1%ers and build their own financial, media and social institutions. But like me, they’re not sure how….

It seems to me sensible to work for reform at all levels: local, national, international. They are not mutually exclusive.

Peer to peer lending and crowd funding is the way forward…encouraging that kind of model will end the stranglehold of private banks. IMHO

Alternative sources of funding need not be an alternative to pursuing reforms at other levels.

Great article. Thought provoking. Will definitely check out the Italians book. Can I also say that I am not a fan of this type face or layout.

Thanks – the books are a good read.

@ Ian Dey “…prospects for independence will remain doubtful so long as the fundamental issues of finance (such as the currency) are not resolved…” I completely agree.

But I’m unable to discern from your post what specific policies you think are both desirable and achievable as far as Scotland is concerned.

Good question. I don’t have a pat answer. I guess it depends on what powers come our way? I think the most pressing issue ahead of another referendum is whether or not Scotland should have its own currency? Amato and Fantacci suggest national currencies have a role to play alongside regional/international – allowing adjustments given trade imbalances – but they don’t discuss the issue in any depth.

Great article about a central issue that is so widely misunderstood – or not understood at all. Again, the media framing of the ‘debate’ around financial reform and austerity politics limits the discussion to exclude the current analyses like those you mention in this piece. (I wish Bella Caledonia every success in its work to help correct this.)

You could though, have mentioned the UK campaign group Positive Money who are closely aligned with the NEF; the Icelandic report that proposes this Sovereign Money solution to the money problem quotes extensively from PM literature:

http://www.positivemoney.org/

Many people raise concerns about the return of this money creation power to a corrupted state like that of the UK, and whilst I can see some of the caveats, I am encouraged by emerging politics in Scotland and the likely adoption of these ideas in Scandinavian countries. In the end, in my view, the money system and the political system are intrinsically linked in ways that are not generally acknowledged in the current conversations about either of these two areas of reform, and it is this democratic angle of the debate that I see as holding most appeal to the less economically literate people who may stumble upon the Sovereign Money idea.

‘Democratise money!’

Thanks Steve – we’ve covered this before and will do so again. We worked with NEF in the referendum, good folks and great ideas

Apologies – I assumed people would get to Positive Money via NEF. I guess we should not set up an opposition between the democratic and technocratic? As for corruption, it assumes many guises and a system that automatically exacerbates inequality can be seen as an embedded form of corruption.

I’m enclined to agree that on large monitors, the typography is quite straining on the eyes.

I have a 1920×1080 monitor, and it looks like this.

http://i.imgur.com/FKt2G8s.png

Good article. One of my, well, many frustrations at the leadership debates in the run up to GE was the lack of any focus about why we are in this mess in the first place. I didn’t hear anything in the way of how any of the parties intended to stop a repeat of 2008 recession.

it was heartening in this article to hear more about money creation and I’m glad SteveB has mentioned the work of positive money. Until we get to the very heart of our monetary system we will solve nothing. It is very worthwhile hearing what positive money have to say about our debt-based monetary system and what we can do to change it…

http://www.positivemoney.org/videos/introduction/3-simple-changes-banking-fix-economy/

Having looked at Positive Money again my opinion has not changed. By coincidence, last week Bill Mitchell – Prof. of economics in Newcastle Australia – posted two pieces detailing the problems with PM. I posted the links here the other day, but that was on an old thread that had sprung back to life so I doubt many people saw them.

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=30827

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=30833

There’s also an excellent disection by Neil Wilson:

http://www.3spoken.co.uk/2014/11/the-sovereign-money-illusion.html

And a post describing alternative changes:

http://www.3spoken.co.uk/2013/05/making-banks-work.html

In short, the PM people have correctly identified the, or a, problem, but their solution is both unworkable and undemocratic.

Thanks for these links – more homework! Sad to see the acrimony generated by an argument over whether and how banks create money. Glad I am a retired academic…

Agreed; the operational reality of where money comes from really shouldn’t be a mystery. It’s an observable fact that the vast majority of it is created as debt by private banks, and also that the majority of it is created to fund unproductive speculation. Where disagreements develop is in identifying the specific problems present in that reality, and in crafting solutions.

I tend to pick on points of disagreement*, but the general direction of your piece is spot on.

* Bill’s writing covers the importance of currency sovereignty in great detail; what it means for sustainability of spending, debt and so on.

New layout threw me, but good article.

Have you an interest in Business for scotland

I enjoy your posts, but I have no specific interest beyond that I hope I share with everyone in Scotland.

I don’t see much hope of change at the UK level as the financial sector has captured the main political parties, through funding, revolving-door appointments, by insinuating themselves into Whitehall as “advisors” in various government departments and by ownership of the msn.

That is why it is called ‘the establishment’ I guess. But who would have expected the Referendum to be so close or the SNP to win so many seats in the GE? The triumph of hope over expectation!

good article and exchanges. However focussing just on money and its creation without considering how the rest of capitalism works as a system centred on exploitation of labour and the need for profit is a bit one sided. To make these links we are running this two day workshop soon in Aberdeen (this will include a speaker from NEF):

Aberdeen Political Economy Group (APEG), IIPPE Training Workshop and IIPPE Financialisation Working Group Invite you to a two day workshop on

“Neoliberalism and the political economy of money and finance in Scotland and the UK”

June 25-26th 2015

Venue: Fraser Noble Building, University of Aberdeen

The UK economy is likely to be the terrain on which tensions will emerge between an emboldened austerity-driven Conservative government unexpectedly elected with a small but clear overall majority, and a triumphant Scottish National Party committed to oppose public spending cuts.

The Aberdeen Political Economy Group (APEG) and the International Initiative for Promoting Political Economy (IIPPE) are therefore pleased to announce this timely two-day workshop supported by the Radical Independence Campaign in Aberdeen. The workshop aims to address fundamental questions relating to the nature of money and the role of finance in contemporary capitalism and how they impact specifically in relation to Scotland and the rest of the UK. For further details, please contact: Keith Paterson at APEG [email protected] or tel 07793 655 410 and http://iippe.org/wp/?page_id=643

Thanks Keith

Hmmmm…..Who won the election? David Cameron

Who lost the election? Ed Milliband

Who was proposing (albeit it, modest) reform of financial sector? Ed Milliband

Who was hoping Ed Milliband would fail? The financial sector, Ian Dey, and many bellaCaladonia readers.

Careful with what you wish for, it may come true.

So its its got to be back to basics then. Re-nationalise all the public utilities without compensation. Establish publicly owned banks. Encourage co-operatives and credit unions. Revive old-fashioned building societies. The stranglehold of the banks and financial institutions must be broken.