Nationhood as Drama – The National Theatre of Scotland and Us

When the 1997 referendum succeeded in securing devolution for the Scottish nation, the Scottish people had to go about reassessing and redefining what it meant to be Scottish in a new age of greater political – and consequently greater cultural – independence.

When the 1997 referendum succeeded in securing devolution for the Scottish nation, the Scottish people had to go about reassessing and redefining what it meant to be Scottish in a new age of greater political – and consequently greater cultural – independence.

Hot on the heels of this political shake-up, the National Theatre of Scotland (NTS) was created; a national institution born out of greater autonomy and a more politically defined landscape. From the beginning, the organisation made very clear choices about its own identity. It turned its back on a permanent home, instead embracing the theatres, theatre companies, writers and directors already working within the Scottish theatre scene.

In doing so they avoided any complicated debate over where a building would be situated – any location would assign more cultural and theatrical significance to that area and would cause questions over why it was chosen and others were not – and it also meant they could embrace the touring scene that has played an important part in Scotland’s theatrical history.

From the outset, the NTS also made it clear that, although they were a national institution and therefore flying the theatrical flag for Scotland, they were not going to be a vehicle for defining any sense of Scottish identity. In fact, founding artistic director Vicky Featherstone made clear that the establishment of the NTS was ‘the chance to throw open the doors of possibility, to encourage boldness’ and not ‘a jingoistic, patriotic stab at defining a nation’s identity through theatre.’

“As a nation we are surer of ourselves when pitted against the things we do not want, rejecting conservativism and choosing Europe over Brexit. But when it comes to what we can or should be, we’re still a little unsure.”

Fast-forward 10 years and the United Kingdom has moved from a Labour majority government to a Conservative majority; has seen the rise and rise of the SNP in Scotland; has debated Scottish independence and kept the Union; and has turned its back on another with the decision to leave the European Union.

Now, just as the political landscape of the United Kingdom seems more uncertain than ever, the NTS’s own fate seems to be in question with the dramatic departure of the organisation’s artistic director, Laurie Sansom, after 3 years in post. The next artistic director will be the organisation’s third and will lead it into the next decade.

It’s already a time of change for the theatre without walls as the organisation gets a new headquarters, dubbed ‘Rockvilla’, in Glasgow, where they hope to create an ‘engine room’ for Scottish theatre. The next director will undoubtedly face challenges, old and new, as we move into a politically and economically uncertain time post-Brexit.

In its first 10 years, the NTS has faced criticism for a wide variety of reasons, a good deal of which seem to be related directly to the fact that the institution represents (or should represent) the people of Scotland. Some have spoken out about the fact that there are not more Scots working at the NTS; it has been accused of ignoring Scottish classics; and its founding director spoke of the difficulties of being an English artistic director and the bullying she felt she received because of this.

For all its wishes – to not be a stab at Scottish identity, the National Theatre seems to have been dragged into the discussion, albeit against its will.

The uglier accusations of bullying and the scrutiny into the make-up of the NTS’s staff are elements of the debate around the NTS that closely reflect an uglier kind of politics that has been rearing its head of recent.

Culture, just like politics, has the eternal dilemma of how best to represent the different needs and identities of a widely dispersed nation. Yet Scotland’s theatrical scene has always been an outward looking one and it would be a shame for our national theatre to be constantly embroiled in debates around the identities of its staff, rather than the power it has to reflect our own shared identities.

The NTS’s choice to work within communities, producing pieces of theatre that speaks directly to individual areas of this far-flung nation was an innovative and bold move for a national intuition. By choosing to be a ‘theatre without walls’ it chose to set itself against the tradition of the UK’s National Theatre, whose home sits on the South Bank in London.

The National Theatre produces shows in this permanent home for Londoners and visitors alike but it has been criticised for its lack of regional touring and, when they do tour, it is often the large commercial hits – only a small selection of their repertoire.

“Some have spoken out about the fact that there are not more Scots working at the NTS; it has been accused of ignoring Scottish classics.”

The NTS is a national theatre that breaks the mould. Their focus on touring and working with communities across Scotland has been a hugely successful element of their first 10 years and this approach is a model of representation that lends credence to the rejection of centralised rule. However, the role of the NTS and the level of debate around it is an example of the uncertainty and debate which lies around the future of Scotland in general.

As a nation we are surer of ourselves when pitted against the things we do not want, rejecting conservativism and choosing Europe over Brexit. But when it comes to what we can or should be, we’re still a little unsure.

Like the NTS, the future of Scotland is now up for grabs, we just need to decide what we want to do with it.

A ‘national theatre’ should surely reflect ‘the’ nation concerned? Yet, like much of ‘institutional’ Scotland, Scots (and hence Scottish culture and language) are seldom given leadership roles, or emphasis, or focus; instead the culture is subsumed by an Anglicised straightjacket. And we are accused of parochialism when we mention this. Many of us know “what we can or should be”, but we need to cast off the unionist/colonial yoke first.

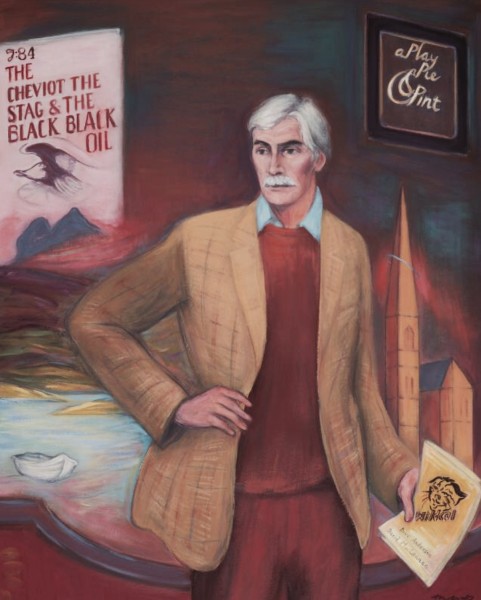

The unattributed portrait of the late David MacLennan by Sandy Moffat was commissioned by Democratic Left Scotland, was gifted to Juliet Cadzow, David’s widow and hangs in the bell tower of Oran Mor in Glasgow.

“The NTS is a national theatre that breaks the mould.”

I hardly think so, judging by the board, which is stuffed full of the usual unionist/royalist privileged elite and titled folks (https://www.nationaltheatrescotland.com/content/default.asp?page=s7_9); hardly a ‘rough Scots accent’ to be heard in that boardroom. They will not tell the Scots their true story. Perhaps that is their true purpose? Hence the generally bland productions.

You’ll not hear a lot of ‘rough hewn’ Scottish accents in the boardrooms of many (any?) of the nation’s major cultural orgs despite the continual refrain of diversity and ‘reflecting the nation back at itself’. Maybe someone for the department of the bleeding obvious can prepare a strategy document on the subject.

I found this article confusing and contradictory. On the one hand it said that it chose to work within communities on experiences reflective of their lives, rather than the national story (fair enough: Scotland is diverse, as MacDiarmid’s poem ‘Scotland Small?’ says) yet was accused of not doing enough touring, and when it did, it performed its more commercial pieces.

Hmph. A ‘national’ company whose original directors’ position was that they had no interest in the Scottish canon. Whose first play had to be recast as no Scottish based actors were involved. And whose initial artistic decisions and direction were handed to non-Scots. Can you imagine ANY other country starting a national institution and allowing someone else to run it?