Scotland’s New Mythology: Alasdair Gray and a new kind of nationalism

But, as inseparable as his work is from the city, Glasgow is even more intrinsically tied to his work, from the split-personality twin cities of Glasgow and the fantastical Unthank in Lanark, to the Victoriana-steeped backdrop of ‘Poor Things’, in which Glasgow is elevated to the romantic, almost mythical status so far reserved in English-Language literature for only Paris, London and New York.

Gray is keenly aware of that the mythology of a city, or a country, can almost overtake it’s physical, brick-and-mortar Geography, at least in cultural memory, and in Lanark he says so explicitly:

‘”Glasgow is a magnificent city,” said McAlpin. “Why do we hardly ever notice that?” “Because nobody imagines living here,” said Thaw… “Think of Florence, Paris, London, New York. Nobody visiting them for the first time is a stranger because he’s already visited them in paintings, novels, history books and films. But if a city hasn’t been used by an artist, not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively.”

“Gray’s nationalism strives for a socialist, inclusive Scotland, one in which art and life are interwoven and synonymous.”

That is, until now; Gray’s novel puts Glasgow firmly on the literary map. The prior artistic vision of Scotland, the one centred on Enlightenment-leading, Athens-of-the-North, hyper-Gothic Edinburgh and surrounded by Walter Scott’s vision of the bleak, romantically untamed Highlands had for a long time seemed to contain a black hole somewhere on the West Coast where a city should be.

This was due in no small part to the overwhelmingly upper-class nature of pre-20th century arts; Edinburgh was the Scottish second home of royalty, the Highlands a playground for the upper class (and never mind the crofting communities that had been forcibly scattered to make room for the majestic stags so loved by postcard manufacturers). Industrial Glasgow, vital city port, hub of shipbuilding and largely working-class may have been economically significant, but from a literary perspective it received little recognition.

As another great contemporary Scottish writer, Janice Galloway, says: ‘As though whispering aloud what I had always assumed a local secret, Gray spoke using the words, syntax and places of home, yet he did it without the tang of apology or rude-mechanical humour, the Brigadoon tartanry or long-dead warrior chieftain stuff I had grown used to thinking were the options for how my nation appeared in print’.

Gray’s Glasgow is not the static, romantically frozen world of Scottish castles, shortbread and Tartan clad highlanders; though it is steeped in Victoriana and more than a hint of high-fantasy, it is dynamic, living, breathing, in a perpetual state of energetic life. It takes the real, working city of Glasgow and elevates it to high art, gives the city an imaginative life not only for Glaswegians, but for all Scots and for readers the world over.

“As though whispering aloud what I had always assumed a local secret, Gray spoke using the words, syntax and places of home, yet he did it without the tang of apology or rude-mechanical humour, the Brigadoon tartanry or long-dead warrior chieftain stuff?”

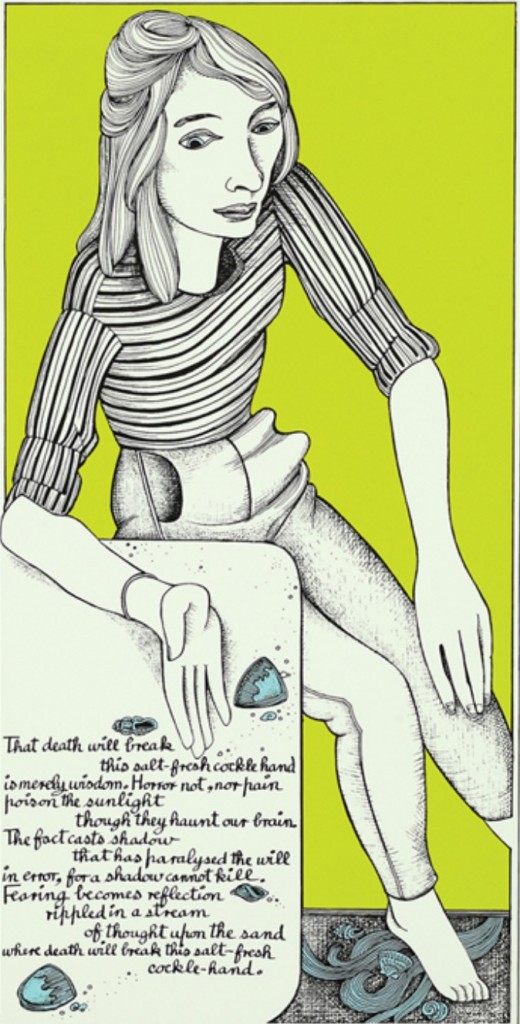

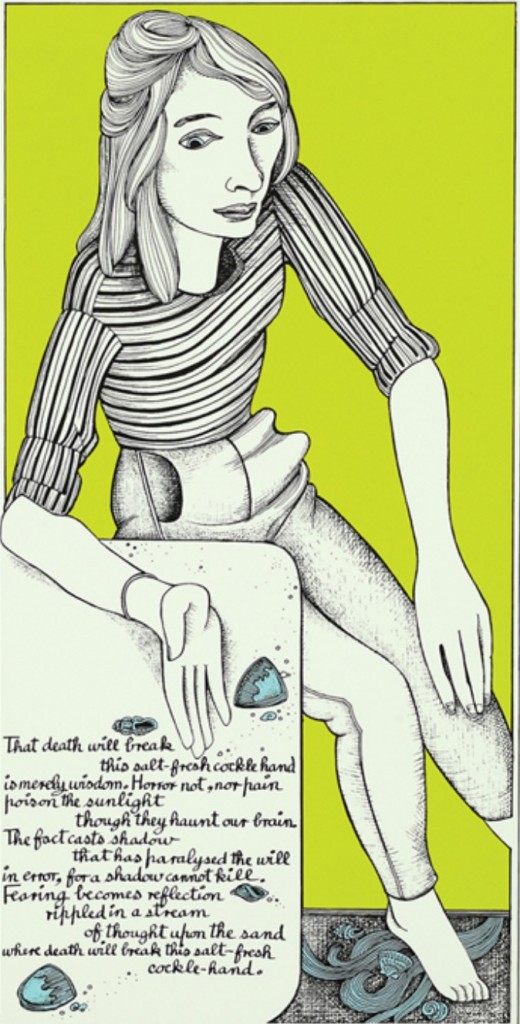

Gray’s high-minded, high-fantasy vision of Scottish identity is not confined to his novels, however: in the form of his publicly-displayed illustrations and paintings, it bleeds through into real Glaswegian life. His mural in Hillhead subway station is a delicate and detailed backdrop to thousands of West-End commutes, his socialist principals proudly declared in his celebration of ‘all kinds of folk’, surrounding a short-and-sweet pair of rhyming couplets to help us through the daily grind without losing our childhood sense of wonder; ‘do not let daily to-ing and fro-ing/to earn what we need to keep going/prevent what you once felt when wee/hopeful and free’.

His work in the auditorium of Oran Mor, a former church turned bar and gig venue, speak of the same kind of hopeful, fantastical thinking. Like a kind of Weegie Sistine Chapel, the vaulted church ceilings are painted in midnight blue and covered with celestial illustrations of the constellations of the Zodiac. Across one of the dark-wood beams runs the quotation that threads its way through all of Gray’s creations; ‘WORK AS IF YOU LIVE IN THE EARLY DAYS OF A BETTER NATION.’

Gray’s nationalism strives for a socialist, inclusive Scotland, one in which art and life are interwoven and synonymous, and in which all of Scotland – living, breathing, working Scotland, not only the fantastical Highlands vision – gets the recognition it deserves.

Makes me want to visit Glasgow again, the place of my forefathers and mothers.

Wonderful artist. “Lanark” was the first book I read which described my own landscape. It is a hugely important, empowering experience to see your own community reflected in art.

His Oran Mor ceiling is breathtaking: https://www.flickr.com/photos/abbozzo/8733878963

An excellent article. Thank you for writing and posting it. Shared.

Well, yes, that last sentence in the article sounds fine in theory. Art and life should be interwoven and synonymous in left-wing socialist Glasgow.

In practice, haven’t folk who admit to liking artistic pursuits always been called p***s in Glasgow?

Also, are most Glaswegians really Scottish given their habitual use of Anglo-Saxon swear words?

Folk who like to think of themselves as authentic Scots should take the trouble to learn to understand an authentic history lesson in verse entitled The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy (it is now online and translated into more understandable English). Swear words and names for embarrassing diseases in Anglo-Saxon abound in 500 lines written in Inglis. Yet almost all present-day writers still insist it is written in THE Scots language. It is not.

http://www.scuilwab.org.uk/assets/flyting-2.pdf

Just the lower classes throw that moniker aboot , usually for reading anything other than a bookies line.

I grew up in a family keen to LIFE read , but no interest in any such other arts.

My grandfather was a prolific reader , mostly of foreign lands , mind you it was usually westerns , written by a guy in Greenock in pulp print , where the only West he had seen was the local victorian Train station , and that authors work now being a cult collectable

My Granda frowned on my reading of comics now called graphic fiction or whatever , other than commando , when I read 2000ad as a near adult teenager he thought my reading would stop. Strangly it was the only comic franchise I probably read. It also brought some understanding of vernacular artists to the fore , scottish ones.

Though arts for me NOW means Architecture , masonry , metal and glass work design , and sculpture – basically something created by anothers hands , or minds if using modern machinery like computers… not essentially what the middle classes would buy a ticket for – even if they could.

I have no need for art to snobbishly compare and discuss its merits vs an.other’s work , though I do appreciate the classic oil works I still wouldn’t buy a print to hang in my homes , but a photo I may have accidentally took at the right time , well thats different.

I abhor unmade beds and pickled sheep as art , perhaps that what the artist was desiring , so well done now I do appreciate it as irony if there is ironic art , but for me that “stuff” just a manky get with questionable hygiene and a failed butcher , though I may look at the metal work involved to see how good the welders seam was!

I do appreciate classical and somewhat eclectic music , dance (usually involving a pole), theatre these days usually more of the operating kind on TVs embarrassing bodies , to see if that smell I have is on this episode.

When it comes to sponsorship vs subsidizing , thats when I sound like those you mention questioning a readers sexuality.

Sponsorship then as kids sure , as teens and students yep , but after that well Leonardo had the church for his dinner bills , buskers have cases full of coins , and cellists can be furniture movers , actors can be waiters and so on. The middle classes though can be sat within their comfy homes , paid for with subsidized wages , for plucking a cello , or interpretive dance routine , where auditorium and venues are empty come curtains up , whereas an artist would do it without compensation between filling shelves as tesco.

There is nothing wrong with engaging with what will expand your art more than subsidy ever will , if you can work unlike students and children , through real life it will bleed into it… regardless. Folks like the ones mentioned in the piece probably did.

How is Alastair Gray doing these days, after his fall, anybody know?

I saw Alasdair yesterday. I couldn’t stay long as he was working on a brilliant Grayian art piece. He’s wheel chair bound, working hard, creating hard, and well cared for.

Thanks so much for letting us know.

Gray’s wee allusion to the difficulties he encountered when trying to “sign-on” the dole while simultaneously his texts were being discussed in European universities, says it all for me.

Neglect, neglect, bloody

neglect.

I may know little about the arts, but I do know what a creative genius is.