The Sinking of the Whale

On the nature of faith, the effect of the lingering horror of war and the dynamics of father-son relationship.

On the nature of faith, the effect of the lingering horror of war and the dynamics of father-son relationship.

“Maxie, Maxie, Maxie, wake up. Wake up! Wake up! I’ve got stories to tell you.”

It’s 4.30 on a summer’s morning in a bedroom of the Manse on the Hebridean island of Iona. The year is 1960. There is an old man and a young child in the room.

The old aged pensioner is sixty-five, his son, this writer, eight. My mother sleeps next door, writhing in the early part of her pregnancy.

“Wake up, Maxie, wake up,” The old man would whisper in my tiny ear. He had a soft and sexy voice. I can hear it yet. They make an odd couple, these two. The old man looks half mad. He is wearing a torn dressing gown, blue and white striped. The hair an explosion of white. The oyster eyes juggly, the collapsed mouth stale with dried froth, snot on the moustache. The eyes like lasers.

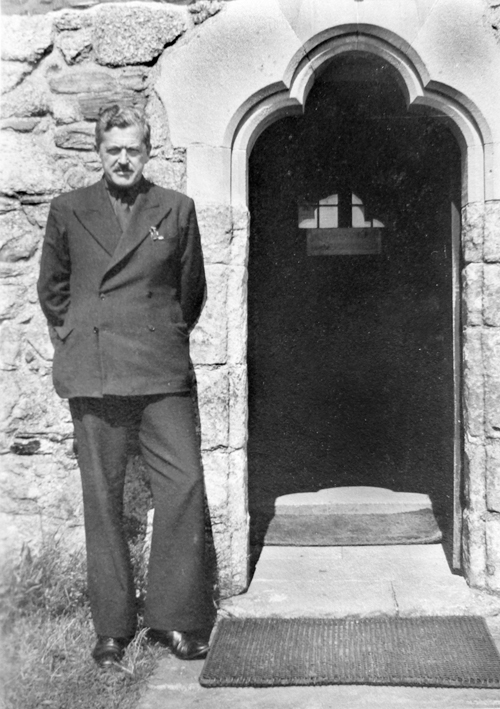

Meet my dear dad, The Very Rev Lord Dr Captain Professor George MacLeod of Fuinary. Military Cross, Croix de Guerre, Doctor of Divinity and, at this moment, quite possibly certifiably insane.

George is tall and was once elegant, though perhaps not so much now as he hasn’t got his teeth in.

Beside him the slugabed child is just a tight little bundle of red curls, milky skin and ‘go-away-I’m- sleeping, Daddy’.

The old man hasn’t slept for thirty-six hours and for six of those hours has probably been too drunk to legally drive a car, a state he prefers when he is writing about his belief in a living God.

He is now so tired he hardly knows his own name. Luckily many others do. Indeed he is quite famous, or perhaps notorious, for he has many enemies.

All night long he has been pacing around the downstairs room with a paraffin pump lamp hissing out a warm yellow bubble of light.

He lights another Capstan (Full-Strength) cigarette, draws deeply on its giddying smoke and drums his fingers hard and fast on the table. He’s writing a three-minute prayer for the early morning Service he will soon conduct in the half-ruined Iona Cathedral lying a few hundred yards from here, his home in the Cathedral Manse. His congregation at that service will be his team for the most exciting project to have taken place in the Church of Scotland for a century.

Sitting at the front of the draughty church in their blue denim overalls will be half a dozen Gaelic masons who will soon be out working, on the rebuilding of the Cathedral walls. With them will be perhaps six clumsy volunteers, mostly young ministers drawn to George’s crazy dream of rebuilding the Cathedral as a symbol of hope for the world. It’s a project that has been born of the horrors he had witnessed in the First World War.

Sitting at the front of the draughty church in their blue denim overalls will be half a dozen Gaelic masons who will soon be out working, on the rebuilding of the Cathedral walls. With them will be perhaps six clumsy volunteers, mostly young ministers drawn to George’s crazy dream of rebuilding the Cathedral as a symbol of hope for the world. It’s a project that has been born of the horrors he had witnessed in the First World War.

Alongside them in the pews will be fifty visitors who have paid to come to week-long conferences in the half completed Cathedral.

His clan of followers may have little money but they are rich in dreams, their day being often jump-started by the sheer electricity of their leader’s morning prayers.

And so in preparation George will hustle and fuss, sometimes all night, to make those prayers pin perfect. Fine-tuning the music within the words, fiddling with the micro pauses, adding just a hint of vibrato… until the prayer moves along like a little red boat that scarcely troubles the water with its passing.

George doesn’t really know why he believes in God; he accepts it’s irrational but still believes. Why? Three reasons.

Firstly, he sees it as being a better option for the kind of world he wants to live in. He wants people to be Christian in their dealings with him and so is prepared to enter a contract to be Christian in his dealings with them. The thought of the world spinning senselessly through space while all mankind simply scramble over each other trying to get the biggest slice of the pie is so instinctively awful to him that he dismisses its reality as being improbable.

Secondly he is culturally a Christian. His family has always been Christian and they have lived lives he has admired, so he wants to believe.

It’s the third element, the mystical part of his faith that keeps him worrying away at his prayers in the long watches of the night.

He feels that there is a radio frequency obtainable in everything that is somehow right, somehow perfect. You only have to work at the fine-tuning handle until the reception is so crystal clear that the voice of God can be heard. Sometimes he will get near to that perfection in a sentence, in a sermon, in an action.

And he clings to this madness as a possible rebuttal to the awfulness of a Godless world.

Then there is Nature. Again and again he will see something so sublime that he sees it as being in that frequency of perfection. He recognises the irrationality of assuming that just because his human mind judges a soaring bird to be perfect does not necessarily mean that the bird has been created by God, or indeed that God exists. But living on Iona with its strange energy pulsating out of the rocks and seeing what may possibly be flashes of the divine in the beauty of Nature, well it’s enough to give him permission to take the leap of faith to which those first two elements of his faith push him.

During four years of the First World War he had been a Captain in the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, leading hordes of Gaelic-speaking youngsters to their deaths and had grown to love them for their mysterious naturality.

On one day alone he had led four hundred forwards over the top and returned with eighty. They had given him a medal.

“A Military Cross!” He had once told me. “My God maybe if I had killed a thousand Germans perhaps they would have given me a Victoria one!”

Ho ho ho; he had laughed at the joke. It was a safer option than starting to cry; perhaps if he had ever started he wouldn’t have been able to stop.

His experience in that first world war had been so horrific that even then lying in that bed, forty-two years after the event he would still hear the cries of the youngsters he had had to lead out of muddy trenches into cold rain sown with stinging bullets that in his own words would ” Unzip their tummies and leave them wide-eyed running forward with strings of warm sausages overflowing their soft young hands…or crack open their knee caps so that they would scream for their Mothers for all of the few minutes until they bled to death.”

He was twenty-two years old, when he witnessed such scenes. Not once but hundreds of times. In one period of three weeks in that war more than six thousand highlanders were killed, and he was in the thick of such fighting for month after month after month.

On one such day his men had seen him jinking and jumping across a dangerous patch of ground until he had joined them in a muddy trench laughing with delight; ” Well at least it’s not raining!” he had joked to their astonishment.

Later some of them were to submit him to a mock court-martial under the charge of being ” Aggressively optimistic.” It was in December 1917, the place, Arras.

He often dismisses the Gaels as being feckless dreamers, and yet their culture haunts him … There had been something about how they lived, something about how they were prepared to die for each other that had been superior to the English culture he had learnt at Winchester and Oxford .

George has an almost manic focus on whatever job is to hand, and is never more obsessive than when he is writing prayers. During the night this focus is often targeted on getting into the mental groove in which he can get on to the right frequency. He knows the recipe to get to that groove all too well.

First make loads of black, heavily sugared coffee, add a little whisky, some Capstans (full strength), plus some doubt and guilt; and then throw in a profound sense that there really ought to be a God.

After getting into this state, his spinning mind is usually able to drill a peephole through the thick door of his objectivity into a misty world that might not only exist, but also be eternal. He scarcely dares to believe in this other invisible world, but is even more frightened of not believing in it. So he kneels and believes and is then able to believe and kneel.

Once he has seen what any scientist would regard as invisible, he will mix a few well-tried ecclesiastical flavourings into his prayers. Using colourful images of the sea, sky, sex and soul he will conjure up a cocktail not only to shake sleepy minds awake, but also stir up their energy for harsh days on high scaffolds, working as they do with heavy granite blocks in the driving rain.

He’s a good man, George. A good man now exhausted. He had been dog-tired when he had started the practising of the prayers and that was now seven hours earlier.

Upstairs, his young wife of 32 lies waiting in her warm bed. Her body yearns to spoon to his warmth, but he grips instead to his older and safer lovers; God and duty.

The Abbey restoration project is constantly with him. He has dedicated his life, his money and almost his entire fevered mind to restoring it. Now he must keep the volunteers motivated to get the thing finished. He must, he must, must…

The completed building, he tells himself, will be half of Nature and half of Man, a bridge between the material and the spiritual; on Iona too, an island where only a veil as thin as gossamer divides the spiritual from the material. The holiest place in Scotland will send out a radio beam in perfect frequency with the divine.

Nature incarnate on a wind-ripped island … Yes that’s on frequency.

A megaphone for God’s still small voice. That isn’t… He practises such phrases out loud, watching the sound as it flies through the air like a wild bird, tasting it as a chef might taste a sauce. Then, if he likes the sound and the flight he will snatch at the beautiful butterfly he has created, pinning it to the ink-splattered paper before him.

It had all been easy enough fifteen years earlier. After the Second World War, former soldiers had flocked to his newly hatched Iona Cathedral restoration project. Such fun then. Such japes. It was just like the war, though with fewer young bellies being unzipped by the machine guns.

The men had lived like campers in garden sheds beneath the ruined walls of the Cathedral, dozens of them, swimming naked in the freezing sea at dawn to charge up their enthusiasm. But then, aged 53, he had fallen in love with a 27 year-old youth camp leader and now there were two slugabed children in the Manse beside the Cathedral.

How many years of work did he have left? Time seems to be speeding up, Christmas comes once a month, and the Abbey lies uncompleted. Oh my God! The child stirs in his bed.

“Oh Daddy leave me alone! I don’t want to come swimming with you before breakfast. I’ll go tomorrow I promise. Go to bed. Mummy will wake you up in time for the Service. Don’t be afraid, she won’t let you sleep in. Go to sleep Daddy; go to sleep.’

The old man falls onto the bed beside the child, his body dropping on to the cheap mattress like a felled ox, the mind trying to will the eyes not to close. The child can feel his collapsed father’s desperation and puts out a tiny hand and prods at the slobber of his Dad’s mouth with baby fingers. He can smell his Dad. It’s a blood warm stew of juicy body stench. The snot, the saliva, the sweet sweat in his greasy arm pits.

But there is salt there too. Salt dust from yesterday’s dreadful douche in the dawn sea, crusted in crevices of skin and held fast on hair. God’s seasoning of the seasoned in the great cauldron of cold reality that is the freezing sea. The child buries his nose in a towelled shoulder and lies floating on an ocean of sleepy odour and utter adoration. The monster that is his father explodes from the blue depths of sleep, aghast at what had nearly happened.

“Maxie Maxie Maxie, get up now, get up. Get up now!” Then George plays his joker,

“It’s still dark. If you get up now you may see the dream moment…”

The child smiles and stretches. The ‘dream moment’ riff’s a-coming. How nice; how very nice.

The phrase has hauled him from sleep. Soon he will rise, but first he must hear his Father’s mysterious tale about the dream moment and the sinking grey whale and taste a spoonful of the sweetness of Nature that awaits him on his barefoot walk in the ice-cold dew.

He hasn’t a clue what his Father’s tale means, he only knows that its poetry is like summer honey to his hungry soul. The one-boy congregation responds to his priest according to their shared secret prayer-book.

“What do you mean by ‘dream moment’ Daddy?” And then the minister will say,

“Well, my darling one; here we lie on Iona, God’s own perfect place and you well know that when we watch the sun go down we sometimes see tiny green flashes.” The boy sighs, floating,

“And so it is at dawn, except it is only those who hear the voice of God like tiny thunder on distant mountains who will know of it . . . the children don’t know it, they are of it, in it, by it, for God is in their innocent faith. At the dream moment God places all the dreams into all the heads of those little children lying safe in their little linen envelopes, and they smile as they wake and sigh as the wind sings the quiet song of Iona.’

‘Sings the quiet song of Iona.’

What a medicine man the old fool was. What a magician.

And then the little boy will say,

“And how will I know when the dream moment comes Daddy?”

And his priest will reply,

“Why, the lamb, Maxie. That lamb will become as still as a rock in that moment. And the seal turning in the wave will pause; the gannet, broad as a man is tall, will not have to move his wings as he slides down the back of the wind, for the very rhythm of life he will be feeling.”

“And the whale Daddy. Tell me about the falling whale…”

What does it mean to be mad? What does it mean to be sane?

The Very Reverend Lord Captain Doctor Sir Prof George MacLeod of Fuinary M.C., Croix de Guerre, was either totally mad or utterly sane when he would come to the answer of that final request.

For the medicine man would be taking his leap of faith, floating on his own sea of either self delusion or incisive exposition, dancing with the white lambs, sliding down the banister of the wind to a place where the existence of God was perhaps proven by the perfection of Nature and his whole cultural being would make sense, and all those young kilted children would not have died in vain.

His reply to my call for the falling of the whale would be a raising of his own weary body. Sometimes he would sit up, eyes shut, the hands grasping the sheets for comfort. My own hand might perhaps be on his towelled leg, trying to be with him in his moment of almost physical passion, the final words squeezed out of the orgasmic cleric in a rainbow of glory.

Utterly exhausted, on fire with nicotine, coffee and whisky, his mind would be flailing around looking for something to grip onto and all that he could find that made any kind of sense would be the nonsense of God and he would reach out to the heavens, aggressively optimistic that God existed, and that there was a difference between right and wrong and that all the kilted children hadn’t died without reason.

“And the great whale, Maxie, oh my Lord, that great grey whale, falling through the white to the blue to the green to the black will turn on its side and it’s empty eye, that eye that has seen the free falling of time, for it is all eyes, that empty eye will gaze upwards and at that moment, at that dream moment, it will both see and be of God.”

Sometimes I would have to hug him as he rid himself of his doubt. Hold him tight in the agony of his brave choice of uncomprehending faith. Sometimes I would laugh, sometimes gasp.

Always I would love him. Always.

And after that? Well after that the old man and the small boy would go swimming before breakfast.

Lovely

Sublime.

Like a Van Morrison song so ethereal and beautiful.

Good article (though I’m not aware Iona has ever had a cathderal).

According to wikipedia he was considered half way to Rome and halfway to Moscow, which is a certain kind of balance.

The abbey has been refereed to as a cathedral at various times.

And the Moscow, not just a reference to his socialism, but also his attraction to Russian Orthodox thought, with which he considered the Celtic Church connected (being pre the 1054 split of the Eastern and Western (Catholic) churches.

Despite not having been the seat of a bishop?

It was the Cathedral of the Isles during the esrly 17th century when K. Charles I was trying to impose episcopacy on the Kirk.

Thanks, that makes a lot more sense.

Sublime indeed. !!!

Profound thanks for this glimpse of the spirit behind the Iona Community and the rebuilt abbey I’ve visited many times.

Having witnessed the restoration of the cathedral using funds raised largely through private donation and read on its significance I would hope to see it being used more in a national sense.

I find it distressing, and indeed wrong, that those visiting Scotland’s most sacred site should have to pay £7 ( I think ) for entrance. It seems that if we are able to raise millions to purchase italinate paintings as they are so essential to the nation’s cultural well being that some kind of central fund should be established to allow free access to Scotland’s only ecumenical Cathedral. I respect those who work tirelessly to maintain the building and understand that it needs funds, my point is that it should be higher up the pecking order in terms of allocation of funds.

Personally I always refuse to pay the entrance, but it’s tough to do this without stressing the poor devils whose task it is to collect the funds. Many thanks for the kind comments, most of the good bits were nicked from my Dad.

If you take the first gate after the Columba hotel and pop into the graveyard to go and see my dad’s grave you can always do a detour and wander over to the Abbey…without paying. But I agree – it’s the principle.

Wonderful poetic and profound words max.

Thank you from another child of a ‘quite possibly certifably insane’ but also truly loving and remarkable father

A wonderful tale Max. You write beautifully

Thank you Joyce, I bought one of your pictures of the old rogue last month and it will a family treasure.

A special moment on a dreich Saturday morning.

Maxwell this is a mesmerising, beautiful piece. Spellbinding-does it break the spell to ask for more?

Wonderful. Remember the Joni Mitchell song? ‘Laughing and crying, it’s the same really’.

He wanted to show you what Reality was, beyond love, beyond death.

So very well put.

An interesting piece, although I remain unsure of it in some ways. A great many Scots folk had relatives who did not return home from WWI, and of those who did return they were never quite the same again. Most who did return came back to face the same as what they left – poverty, inadequate housing, unemployment, near starvation, alienation, poor health, and all too often the only option for them was emigration. However, those from the professions/educated upper/middle classes, despite the fact they also were sent to participate in what was really state/elite-organised murderous mass slaughter, continued to enjoy important socio-economic advantages on their return. Arguably the faith of the working classes would have been tested rather more.

You raise some interesting points Sir. Yes I think the faith of the soldier might well have been tested even more than the young officer, though it should also be noted that the life expectancy of a platoon officer on the front line was often weeks more than months so it wasn’t entirely loaded in favour of the elite.

For example the memorial plaque at Edinburgh’s New Club lists over sixty killed from that one club alone.

Perhaps the most damning element of the folly of the class divide was the low quality of so many of the decisions made by people who in terms of ability did not deserve to be given that responsibility, maybe that is why the class sys

tem took such a knock after the conflict.

I’m not sure the class system has taken that much of a knock over the past century, given who still today rules over the great unwashed masses in Scotland: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/elitist-scotland

Abolishing private schools and reforming ‘elite’ universities would be necessary for real change.

I would dispute that the class system

hasn’t been radically changed in the last century. Class is now based more on money than inherited social status. Both are of course undesirable though I do like people having pride in their families

Even the poor and non-intellectual can have “pride in their families”.

So glad this came our way, Max – will love going over it with Mary when we see her next week. Thank you indeed – lyrical stuff, where did you get the gift. . . .?!

I had a good Latin tutor called John Harvey and a good Nannie called Molly Douglas, heaven knows what happened to them.

And, I meant to add, thanks to Maxwell for that lyrical, honest and insightful piece.

A year or two or three later – if my memory serves me right (and I doubt it does, for I would have been 2 or 3 or 4 years old) – I remember pinching the trowel from you or Neil with which you were laying the foundations of one of those restored wings of the Abbey-Cathedral as it took flight.

The power of the islands is phenomenal, from Iona’s power to restore the inner cities across what then was Britain, to Eigg’s to restore the belief we can be a better society than the one our ‘betters’ tell us we have to settle for.

And in between is the story of tiny Isle Martin where a young couple’s planting of indigenous trees in the 1980s began a cascade of ecological restoration across Scotland with the Tree Planters Guide to the Galaxy, Reforesting Scotland, and much more.

There are dreams more real than waking, which waking from impels us to remake the world.

I guess every day we remake the world: afresh? or as ever?

Your piece is a real joy to read:

Where have those tumbling tussling struggles over God gone, as church after church shuts up shop?

Today we heard that we’ve been granted the first Urban Community Right to Buy, so we can set about raising the cash to buy the Old Parish Church in Bellfield Street, Portobello. It’s sale the result of the merger of three Church of Scotland churches into one. That one is still dynamic but it is so clear that these churches are vanishing from our lives. Surely it’s incumbent on us all to reclaim them from the ‘developers’ so we can continue to develop as communities rather than be ‘developed’ into glorious consuming isolation.

I have been waiting to get my revenge over you stealing that trowel for over fifty years and revenge is a dish best served cold.

So here goes. I need to know what you are going to do with that Church. After all if you get the cash ( which I hope you do ) most of it will come from the state, so is this the start of the re-establishment of the Kirk? I’m only half joking, the Kirk as currently defined is a busted flush and seemingly incapable of meeting modern needs and now you, a respected contemporary social activist known for his free thinking and raised the son of a leading innovator are proposing to take over a fully functioning building located in a fast rising part of town. What are you going to do with it? Please dont use the words heritage centre, survey or being in your reply/ Now is your moment, trowel pincher.

Regrettably Justin cannot conjure up a personal reply.He will require to consult widely with the community and come up with a plan that fits the strict criteria required by the new legislation in order to make this work at all.

The spiritual element is in the mixing of all this red tape and nonsense by disparate groups and individuals in the locality to produce a plan which formally transfers the old building into the hands, not of a withering presbyterian parish, but to a new community wishing to work together in new Scotland.

How I wish it were all that simple. I have been active in supporting community buy outs for over twenty years, but if we take expensive to maintain buildings out of the hands of established state or institutional hands you are often moving to the reliance on private trusts. These are often controlled by bored, wealthy people and you can be in a worse position than before.I would urge less broad inclusiveness and more clearly defined vision and purpose, though confidently expect to be ignored, though very best ofgood lu ck to you.

Maxwell,

Somehow I feel that I have heard this before. Wonderful to read it again.

It’s a much enriched version of something he shared around a few years ago. Indeed, this is some of the most sublime spiritual writing I’ve ever read.

Praise indeed

For me, this compelling account of George,s faith affords an insight into balancing the moral imperative to act and bear witness alongside the continuing abnegation of dogmatism in matters of the spirit.

You are partly right Rob I did a shorter audio version for Radio Scotlands site few months ago but they edited out some of the blood and gore. and a few if the more controversial bits though to be fair very well.They were excellent.

This is the first time its been published in its full version

The BBC were probably wise. I once met a man who told me. I swear this is trjue who observed” Ive always seen God as being the sort of chap one would only be too delighted to have to ones house for a spot of shooting.”

Which I suppose was rather conterary to my Father tGeorge ‘s position.

“I have become all things to all men, that I may by all means save some.” – St Paul…

Probably a terrible shot, but I imagine he’d have given it a go.

Very evocative piece -takes me right back to days of my early childhood spent on Iona, late ’50s, early ’60s. I remember the Abbey before it was restored. Used to run barefoot around the ruins and dance on the graves of the kings of Scotland! Just as clear I remember the sunrises and sunsets there, and the seals and lambs who seemed like other children to a 4-year old.

So beautiful. Thank you

Brilliant and tender, Max. Thanks. All we need now is to get more people living and working on Iona and on every Scottish island. If the Highland dead of WW1 desire a memorial the surely it is this?

Thanks George

To recieve kind words from Alastair and George on the same day makes it special

My increasing conviction and indeed motivation is that in an Internet world the role of the islands should be as an educational resource through which those living in urban situations can find context for their decisions

Every British child should know the story of eigg and the restoration of Iona Cathedral and the evacuation of St Kilda_ these are tales that can inspire debate and developed economic integrity on the islands as people go there to visit the locations of iconic events events

which they have learnt about it through engaging Internet connections

Maxwell, thank you for your words. Your candour and humanity are deeply appreciated. Dennis Potter, has a phrase, “the ache of life”, and I felt it in your prose. Both yours and that of your father, whom I met a few times when I was an assistant minister at St Giles’ Cathedral.

For most of us in our generation, who didn’t have the brutalizing experience of war, we can only wonder that the insanity didn’t utterly wreck the survivors. I for one, without that military background and that honed sense of duty, would admit that the “spooning warmth” of Kate in a “linen envelop” has always held sway over the pull to my desk in the wee small hours to hone my prayers. Your phrasing and choice of words can be sublime.

My Dad’s silence and emotional restraint throughout our years of knowing him were perhaps explained when he died two years ago and we went through his desk and found his medals. They had never been taken from their box, let alone worn, but they spoke of action in N Africa, landing at Salerno, the siege of Monte Cassino, some of the bloodiest episodes of World War II. Stuff he never gloried in let alone spoke about. I often wonder what it might have unleashed if he’d really opened up. But the silence, the stiff handshake, the dutiful churchy kindness was all we got, but in the midst of it a kind of love, and honour and dignity that shaped us and infuriated in equal measure.

And then there’s faith, this barmy, irrational clinging on, the church a “busted flush”, which it certainly is. How crazy is it to go on believing, trusting in the face of all this nonsense and stupidity and, it seems, so much wishful thinking. There is another great Argyll man, Donald Mackinnon who wrote of the “remote metaphysical chatter”, the breezy optimism of the paid believer who thinks it his duty to serve the ecclesiastical authority, not realising that the lace and robes he wears pay more lip service to Caiaphas than to the Galilean peasant. “The lacy cuff waving a benediction over the launching of a nuclear submarine” is one of his images that haunts me still. So why cling on?

A few years ago, I introduced a rough-hewn wooden cross into Greyfriars. It was probably big enough to have done the job for which crosses were intended. A group of friends had carried it to Faslane as a protest; and they sort of dumped it on us on their way home. There were two reactions that got to me. One was a joiner who helped us set the thing up in the church and said he was uncomfortable putting such a rough object in a building like Greyfriars that had such fine furnishing and ornamentation in it. The other was a woman in the congregation who said she didn’t much care for its looming presence and it might be better re-erected down at the Grassmarket Project, amongst the rough sleepers and the homeless and the mentally ill. Of course, I bristled, but maybe Beatrice was right. It’s the cross that draws us in. It isn’t a refined object, it’s an instrument of torture, promising the worst kind of death and “grown men calling out for their mothers” as they slowly asphyxiate and perish. The cross approximating in one life to the horrors of the Somme or Monte Cassino or Aleppo today, where lives are shredded so easily.

So, there, at Golgotha, the place of the skull. What a defeat! What an exercise in pointlessness and folly and meaninglessness. It’s all there, even in the words from the Galilean’s lips – God has deserted. Glory has departed. And of course God isn’t up there looking on, extracting his pound of flesh from a wayward humanity – his ransom. What a heartless beast of a creator that’d be. But something’s happening – the strange reality of survival, the odd, irrational impulse to hope, to love, to rebuild, to salvage, transcend and maybe even to heal some of the brokenness that blights us and goes on imaging more messed up ways of making the lives of others and the life of the planet intolerable.

And yet, every now and then, out in the green, under the canopy of stars, in the embrace of a lover, we get the odd glimpse of the glory in the midst of the decay and destruction and ache of life. So, we cling on. Some of us think we should crash land the ecclesiastical Lear Jet and get back into a coracle, but we are not brave enough, not honed and seasoned by the agony of war and human depravity. Not sufficiently reckless, or as you father said, “we are too respectable for the downtrodden”.

But then there’s the cross that Beatrice said we should relocate at the Grassmarket Project, and in the midst of all our “do-gooding”, all our faux attempts to right the wrongs and heal the wounds, what happens? Well, we re-hear the stories of the Galilean peasant, who loved the adulterer, who asked the crazed man who self-harmed, “what’s your name”, who asked the blind beggar, “what do you want” and again and again gave people their worth, pointed us to the wisdom of the poor and those who’ve been savaged by life and felt its ache. And Columba, or was it your father, sometimes the two seemed to get muddled, tells us, “Often, often, often, Christ comes in the strangers’ guise”.

And that’s what we mean by the strange reality of survival, the odd illogic of the cross that this Galilean is to be found among us, and often in those who have the most wretched tales to tell but the deepest wisdom to share. And so the church, this busted flush, it’s a joke, a foolishness, an exercise in vanity, hubris and a whole heap of wishful thinking and blind alleys – not the least of which is the barmy idea of the Christian Empire. Success is not a Christian word!

But in the midst of it all, I suppose we cling on, if only because we know, in a way that does no justice to the idea, that in picking the rose, there will be the thorn; that broken hearts learn the character and endless and rewarding landscape of love and its seemingly inexhaustible nature, and that you “turn but a stone and an angel moves”. Was that your father or Columba?

Thank you, Maxwell.

I have very fond memories of getting old fashioned sweeties from George on a few Iona ferry crossings. He was a very old man by then but held great fascination to me as a wee girl.

Dr Frazer

Thank you for your fantastic reply,I hold your witness in theCannongate experiment in high regard and hesitate to c hase you into a corner, but the core question brought up by the essay cant be ducked.

When you say your prayers do you believe that someone is listening or is God just some kind of intellectual construct?

Sir Maxwell, you seem to assume a separation between God and self. You really must become either more Biblical, or more Hindu, in order to grasp the mystical metaphysical George MacLeodesque reality. Both traditions say much the same thing on the question you pose. Specifically, the former says we become “participants”, or “partakers” in the divine nature (2 Peter 1:4). Your question to Richard is therefore a moot question.

But forgive me. I’m just back from being out in the canoe all afternoon. Got 3 mackerel. Eaten already. Even old Attie would have been impressed at that, and 45 mins from Glasgow and as the clocks go back. You know, I also saw a seal come close up, and a wee sea trout leap a yard out of the water. It was off Cloch Lighthouse, Gourock. Is there anybody listening, you ask, when we say our prayers? Well, kind of, when you’re out there in the auditorium. What did your old man call his book of prayers? Wasn’t it: The Whole Earth Cries Glory?

Sir Maxwell, I’m only saying this secure in the knowledge that hardly anyone, your good self probably included, will still be following this thread now. Bless.

I felt bad about pushing at Dr Fraser he is such a nice man and does great work.

However I’m increasingly of the opinion that many ministers imply to their congregations that they’re having a dialogue with a living god when really their own opinion is a an entirely different complex piece of intellectual gymnastics that they hide.

this seems to me to be fundamentally dishonest

over many years I have asked countless theologians whether they believe that a living god listens to their prayers and I have no memory of ever understanding a single reply I’m afraid much as I love you you go into that category

one of the fascinating things to me about the current surge of interest in nationalism is the spiritual element of the philosophy of so many of the believers. They have lost a sense of community, a sense of belief in the Kirk, socialism, capitalism

I don’t understand it any more then I do the clerics being dishonest to their congregations about their beliefs but my own Instinct having witnessed so many wars at first hand and walked with a gun on the streets of Northern Ireland is that nationalism whilst often so beautiful as a Sapling seldom grows into anything as beautiful as the dreams of those who sacrifice so much to nurture it

As I get older, I become less and less cynical about what is possible. And more and more cynical about those who would persuade us that little is possible.

As for Bellfield, (we’ll see what comes out of the community consultations – hat tip the strange comment above, but) my main hopes for it are that

(1) the halls continue to be used by all the community groups (from kids to ancients) who have created this community as they use this space, and that

(2) the church building continues to be a celebratory space for marriages and funerals and the like – a sacred space where people are challenged to find their own way of expressing the fundamental meaning of their lives, whatever form that takes.

As for funding etc. My original plans (before hearing that the Scottish Land Fund now stretches to cover urban areas too) was to develop holiday accommodation out of one of the halls to help cover the cost of repaying a mortgage to buy the place, since Portobello has become Brighton by the sea, but with the softness of sand underfoot instead of Brighton’s boulder like pebbles.

We’ll see

The kirk is in chaos. Over two hundred vacancies and less than twenty coming through to fill them unsubstantiated figures

In addition refusal by some parishes to maintain ancient buildings

This could be an interesting model for the future-lets talk