The unco Leid: stravaigin in a tongue that wisnae ma mither’s

Whan Ah first cam tae Scotland, three years syne, Ah didnae ken ony Scots. Ah haed aye read a wee bit o Burns, an Ah kent thare wis an unco Caledonian tongue at wisnae Inglis nor Gaelic, but yon wis hyne-awa, fair remote an unpossible tae win at fir an ootlander o ma ilk. Fur a Frenchman newlins arrivyt in Scotland, it wis arredies a muckle haundlin gettin ma heid aroon the Scottish tuin o Inglis, an Ah haed nae time tae pit aff fir yokin wi ony ither queer wurds, dialect, leid or whitever yon micht hae been. A guid pairt o ma first year in Scotland wis syne gey forgitfu o the Scots’ unco tongue.

Whan Ah first cam tae Scotland, three years syne, Ah didnae ken ony Scots. Ah haed aye read a wee bit o Burns, an Ah kent thare wis an unco Caledonian tongue at wisnae Inglis nor Gaelic, but yon wis hyne-awa, fair remote an unpossible tae win at fir an ootlander o ma ilk. Fur a Frenchman newlins arrivyt in Scotland, it wis arredies a muckle haundlin gettin ma heid aroon the Scottish tuin o Inglis, an Ah haed nae time tae pit aff fir yokin wi ony ither queer wurds, dialect, leid or whitever yon micht hae been. A guid pairt o ma first year in Scotland wis syne gey forgitfu o the Scots’ unco tongue.

Forby, thro the first months, there wis naethin tae mind me o it. Ah wis studyin at the University o Sanct Aundraes, a braw airt fir learnin but whilk turns gey orra whan it comes tae mirdin wi the braider kintra. Atweel, it’s misbehauden tae speik onythin else nor a mensefu Inglis in the East Neuk’s muckle toon, an aw ma Scottish pals haed tae haud doon thair Scots tuin fur tae compluther wi the general speerit. That, o coorse, wisnae clear tae me. As a French lad, a muckle rowin o the “r” wis braw eneuch, an Ah cudnae see whit wis agley ahint it.

Hooanivver, as pals becam freens – or e’en mair – unco wurds stertit tae brak thro an git tae ma lugs: “braw”, “daftie”, “tatties”, “dreich”, “awa”, “frae”… Yon wur new phrases, new souns, an invitation tae stravaig ootbye the mensefu mairches o the university. Yon mindit me o the wurds o Burns Ah haed read afore settin aff frae France : “yon birkie cawd a lord”… “let us dae or dee” … “caw the yowes tae the knowes”… Yon unco tongue wis backlins comin tae me thro the door o luve an freenship!

Dumfoonert, Ah speirt: dae ye really speik like that at hame? An Burns, dae ye unnerstaun it aw? Why hadnae ye telt me ye wis bilingual? But it wis owre late tae git real answers tae ma speirins. June 2014 cam roon, ma excheenge year wis endit, an Ah haed tae gang back tae Paris tae stert a twa year Maisters in Historie. Ah gaed awa frae Scotland wi the feelin that Ah haed misst somethin. A meestery wis ahint me, unsortit.

Three months efter, thochts o a free-staunin Scotland wur tint anaw. Anither sun wis doon an things wur gittin oorie. Ah haed tae forgit Scotland an concentrate on ma wark. Ma future wis in France efter aw, in a real kintra, wi its gallus leid an its auld Republic. Aye, Ah haed tae forgit, yet Ah cudnae. Luve, freens, an yon unco wurds wur birlin aroon ma heid an fillin ma hert as suin as ma thochts wur free.

Whit wis yon leid Ah haed misregairdit an that ma freends cud speik, tho thai haudit it doon? Whit wis e’en its name? A wee bit o resairch makkit it nae clearer. Wis it “Doric”, “Lallans”, “Dundonian”, “Glaswegian”, “Fife” or “Shetland dialect”? Sic a wee kintra an yet naebody said ocht aboot sharin their lead thegither! Wis the linguistic continent Ah wis seekin juist a few parcels o idioms? Yon thocht gart me be gey disappyntit. Wis yon tongue owre orra fir Scots thairsels an Burns nae national, but anely Ayrshire’s bard?

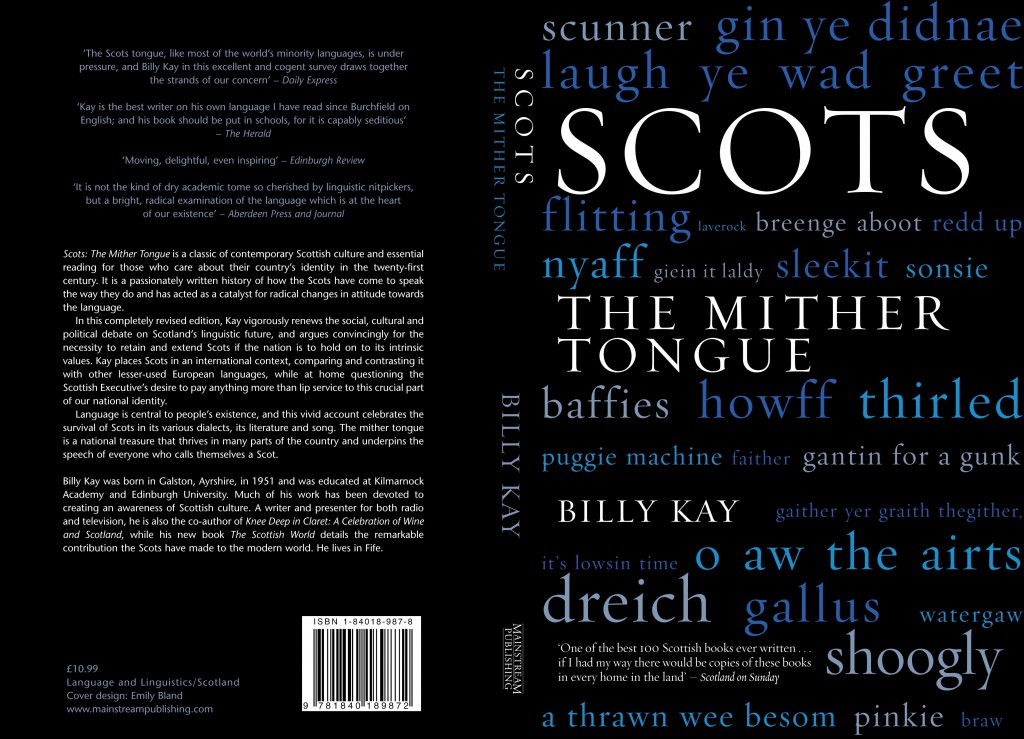

Ah haed tae unnerstaun at it wisnae a bleck or white maitter. Scots wis like aathing, it haed a lang historie, an a gey sair trauchle o a historie it wis! Piece by piece, bletherins wi ma freens an langer readins learnt me aw that. Ane beuk, Billy Kay’s Scots, The Mither Tongue, wis particular important. At lang an last, Ah haed ma answers: Scots wis a real leid that haed lang syne been spoken by the Scottish monarchs but whilk haed gaed thro mony a dour time. Frae the Reformatioun up tae the 18c an the Treaty o Unioun its influence haed been aye taken doun an until the noo it wis maistly the common fowks, frae the pitheids, shipyairds an schemes o the central belt tae the ports an clachans o the landwart North East an the Nordic-farrant northern isles, that haed preservit yon wurds an grammar. A wee bit in Glesgae, a wee bit in Dundee, a wee bit in Caithness, a muckle bit in Buchan, Kirkwa an Lerwick: the mither tongue haed been sauft by the fowk, haudin oot in a hamely daurkness agin the “enlichtit” social scorn.

Mony haed been ettlin at gaitherin aw thae linguistic pairts an knittin them thegither tae mak a new an modren leid. Frae Hugh MacDiarmid, Lewis Spence an Douglas Young, the muckle interwar makkars, tae countless ithers an aw the fowk syne commitit tae the Scots Radio, the Centre fur the Scots Leid, The Scots dictionar(s), the Lallans review. As weel as thaim, the mony Scots furthsetters sic as Itchy Coo, an aw the contemporary makkars an scrievers that haednae stoppit creaitin, shaipin an pittin thegither auld an new wurds, Ah wis airtin oot an dicoverin that the Scots continent wis gey leevin-like. Tae be shuir, few o them greed wi ane anither: “yon spellin wis wrang”, “yon poem wis owre superfeecial”, “yon ane wis an eejit”, an aw that…

That didnae maitter tae me. Aw yon virr Ah haednae expectit, aw the passion that wis pittin intae Scots wis arredies a braw thing: the Leid wis less dwynin mair risin, an it wis wirth learin it – parteecular as Ah wis hinderly gangin back efter twa year in Paris. Ah syne yokit masel tae a lang an ongaun ettle that gart me luve an think on Scots e’en mair as Ah gat tae ken it.

Fur amang aw the different spellins an the argie-bargies aboot the richt way tae yaise the Leid, a general ootline wis appearin, a bonnie ane. Whiles Modren Scots haed keppit the auld appeal o the laund, the eildit sang croonin the plicht o the fowk, an aw the weary weirds o the forgotten sauls o Caledonia; forby it wis muivin forrit, an mibbe wud hinderly rax tae some kin o staunart, a common grund respeckfu o aw dialects yet allouin ilka bairn tae lear it, ilka makkar tae scrieve it, aw Scots tae blether wi ane anither an a new Scottish Commonweal tae flouer frae Elgin tae Dumfries.

Scots wisnae ma mither’s tongue, yet Ah’m learin it, fir Scots is the future. Scots is the laund an the fowk, but it’s the hale warld forby. It’s the sindry vyce o Scotland tae ither natiouns an tae its future weans, whither native or fremd. Ah ken Ah’ve a gey lang way aheid o me yit; Ah ken ma Scots isnae perfit an Ah kenna gin there iver will be a perfit Scots; hooanivver, whit Ah hiv cam tae kennin is that aw thae uncertainties aboot the Leid arenae a sign o doom but o a new day dawin , a blythe new mornin fir a new kintra.

There’s nae pynt in creengin, there’s nae pynt bein reid faced; it’s heich time the warld kent Scots dinnae speik coorse Inglis, but aye juist Scots. Be bauld, be gallus, be fresh an gay, speik Scots tae yer boss, tae yer professor, tae yer MSP, tae yer Pairlament, tae yer readers, tae yer jo, tae yer bairns an tae ootlanders an aw. Dinnae be selfish nor hame-drauchtit, speik yer leid an gie’s yon bonnie wurds. Mind on the stravaigers that bidit in yer laund an wantit tae luve it wi yer mither’s wurds.

Paul Malgrati:

A Historie graduate o Sciences Po, in ma hame ceety o Paris, Ah hiv juist gaed back tae the university o Sanct Aundraes, whaur Ah did an excheenge year atween 2013-2014, tae yoke masel tae a PhD on the poleetical yaises o Robert Burns’ memorie in 20c Scotland. Ah’m gey blythe tae be back an tae forder Scotland’s cultural an poleetical cause in ony wey Ah can.

(Mony thanks tae Ashley Douglas fir helpin me read owre yon).

A’m a furrin lairner o Scots tae, an it wis rare tae read this! There’s aften a assumption in Scotland that lairnin Scots is aw aboot revivin the Scots leid that’s hidden inside ye, but whan it juist isna there ava, that daesna wirk, an ye’re tae some extent on yer ain, sae it unco guid tae see that ither bodies haes fund a wey tae.

Paul

That was fantastic!

John Page

Having a similar experience in Switzerland – it’s exciting to be mistaken for Swiss now but more importantly it’s empowering to speak to my students on an equal footing and reassure them that they’re starting out bilingual and already have a lot of the skills they will need. And I love our exchanges – recently I taught ‘to giggle’ but received gigälä in return – and they laughed when I asked how to spell it: Si, Si chunnts schriibe so wie si wänd! You can write it however you like, there aren’t any rules!

It’s gey lichtsome tae hear thir thochts oan Scots fae a French perspective, an in sic braw an hertfelt Scots. Maist insichtfu is perhaps whaur Paul haes scrievit hoo he speirt, upon hearin his freens speik Scots mair aften, ‘Why hadnae ye telt me ye wis bilingual?’. Fur that’s jist it: Scots is a braw an prood leid o its ain, no coorse English, an Scots speaiker are bilingual, flittin atween Scots an Inglis the hale time, no lackin in education. Here’s tae seein oorsels as ithers see us a bit mair. Muckle thanks tae ma guid freen Paul fur helpin us alang the wey.

A gey inbeirin airticle, awfu weel pit thegither.

Whaur is oor Scots Language Act, Nicola? A refuise bi the state tae taucht wir ain leid tae wir ain fowk and bairns is nae mair nor racial/cultural discriminashin. Whaurs the equaliti in thon? Whaurs the equaliti wi thon Gaelic Language Act (or e’en thon furrin ‘English’ leid!)? Thoosands o English teachers in wir schuils yet nae Scots leid teachers! Whits gaun oan?

I came to Scotland at the age of three, having English as my mother tongue because I had an English mother. Mind, ah hid a Scottish faither wha wid sometimes speak tae me in ither weys, but it didnae even begin tae occur tae me that whit he wis usin wis a different leid till ah went tae the skool. Even then it didnae quite penetrate fur the teachers aye spoke in the same wirds as ma mither, forby it soonded no quite the same. It wis in the playground that ah began tae realise ah wis bilingual. At home with my parents and to my teachers I spoke English (though ma faither wid aye try tae teach me to say wirds lik speuggie an the like) but I soon learned that I had to find a way to straddle the two languages. In the playground I was teased (these days no doubt it would be called bullied) about my English accent and for being ‘posh’ because of it. So ah hud tae mak a decision if ah wantit tae huv freends. What happened was that I decided I would not be bullied out of my English accent when speaking English at home and to my teachers, but ah wid speak a kinna Scots tae mah freends in the playground an efter the skool wis ower, jist still wi an English accent, though this soonded awfy funny at times, ah admit. But ah wisnea gonnae be made tae gie that up for onnybuddy jist cos folk wis tryin tae mak me. So I would ask for a hurl on a friend’s bike, or offer a drink of my skoosh, evolving my own form of language in which I fully understood my friends’ Scots and continued to speak mostly English but enriched with Scots words. Thon wis the wey ah grew up bilingual though ah still didnae quite unnerstaun whit that wis, or the fu wirth o it, till ah flitted doon sooth efter ah graduated where Ah fun ah wis continually usin wirds mah pals doon there didnae ken an ah got confused mahsel, constantly huvin tae spier if a wird ah hud jist used wis an English wird they could unnerstaun or no. The confusion in my listeners was even greater because I’d be asking the question in my long-retained and fiercely-defended middle-class English accent. Yet those often untranslatable words and expressions (what —exactly — is a fankle? Or, how can a guddle result in a boorach?) are the real gift of the bilingualism most Scots still have because both English and Scots are our birthright languages. (I regard myself as a Scots not least because of my own informal early education in bilingualism.) We can not just speak but, importantly, think in both languages. An ye cannae whack it.