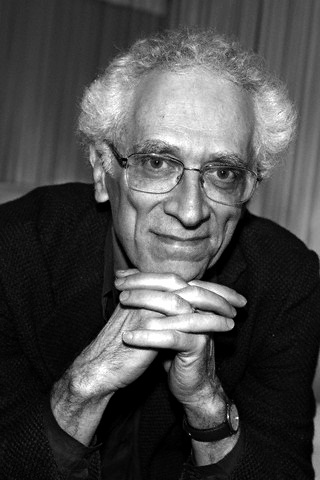

Remembering Tzvetan Todorov

Last week, the French-Bulgarian intellectual, writer and historian of ideas, Tzvetan Todorov, passed away in Paris at the age of seventy-seven from a degenerative illness.

Last week, the French-Bulgarian intellectual, writer and historian of ideas, Tzvetan Todorov, passed away in Paris at the age of seventy-seven from a degenerative illness.

Todorov was born in 1939 in Bulgaria, and when under Communist rule, he moved to Paris in 1963 and soon became a French citizen. He studied under the famous linguist Roman Jakobson, and moved in the same circles as such notable thinkers as Roland Barthes. His early works are primarily concerned with literature, linguistics and language, such as his well-known study of Russian Formalism, the figure of Mikhail Bakhtin, and literary genres.

Over the last two decades, however, Todorov moved increasingly away from over specialization to become a true European polymath, with intellectual concerns which stretched from primitive Flemish painting, to the intellectual figure of Spanish painter Goya – whom Todorov compared to Goethe – as well as the conquest of America and the discovery of “the other”.

Increasingly too, Todorov’s writings became concerned with the cause of democracy and individual liberties, which he declared to be in danger, and what he saw as the steady erosion of Western democratic values by the forces of unfettered neo-liberalism.

As he put in in a recent interview with the cultural supplement of Spanish newspaper El Mundo:

“After the fall of the Berlin wall, new ideologies emerged, the hard-line neo-conservatism and neo-liberalism which govern Europe and the world today, and which weaken the basis of democracy. Democracy is based on the sovereignty of the people and individual freedom. Under totalitarianism, the hypertrophy of the collective supressed individual freedom; today in Europe, we are witnessing the frenzied expansion of the collective as a result of the domination of the economic sphere. The neo-liberal doctrine which governs us today holds sway over and above political power, protects elites, and, in such a way, undermines society”.

In his The Fear of Barbarians, Todorov argues that all cultures are inherently mestizo or hybrid – think, for example, of the importance of the Bible, a book from the Middle East, on Western culture – and tackles issues such as the phenomena of mass immigration and multiculturalism, Islam and the West, and the politically charged usage of terms such as civilization and barbarity. Todorov rightly contends that civilization and barbarity always co-exist within societies and that to confuse the fruits of civilization – for example, works of art – with civilization itself is a grave mistake. His book is a measured and rational rejoinder to the hysterical and catastrophist school of thinkers like Oriana Fallaci, and their political equivalents like, Nigel Farage and Donald Trump, who equate the arrival of Muslim immigrants to the end of Western civilisation.

In The Fear of Barbarians, published back in 2008, Todorov almost prophetically warns that “it is the fear of the barbarians which threatens to turn us into barbarians today”. A quick look at the news headlines in the United Kingdom and the USA today would suggest Todorov is absolutely right.

Todorov’s more recent works are books such as The Inner Enemies of Democracy, in which Todorov lambasts the neo-liberal conceit of the end of History and warns that the biggest danger to democracy lies in the heart of western societies themselves, more specifically in the neo-liberal hubris which led to the invasion of Iraq, Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay. Todorov goes on to name the three great enemies of democracy of our times: messianism, populism and ultra-liberalism.

Todorov’s final book, published as Insumisos in Spanish, or Resisters as it might be called if translated into English, was published just last year. Here, Todorov recounts the lives and feats of a series of individuals who refused to accept the status quo and fought against all the odds for political change. The book pays tribute to historical figures such as Dutch concentration camp diarist Etty Hillesum, French resistance fighter Germaine Tilion, the Russian poet Boris Pasternak and Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, as well as freedom fighters like Nelson Mandela, Malcolm X, and Edward Snowden.

With the unfolding of the deeply concerning political events of 2016, the loss of a European intellectual of Tzvetan Todorov’s stature is a huge blow to the cause of liberty, democracy and human rights in the world today. By reading him and talking about his ideas, we do the small thing we can to mitigate that loss.

***

Support Bella to continue publishing with a monthly donation by Direct debit.

Go Cardless for £5 £10 or £20 a month. Donate with GoCardless HERE.

Thank You

“Todorov was born in 1939 in Bulgaria, then still under Communist rule.”

Really?

Thanks Hector, fixed now

Thankyou for introducing me to Todorov. Very stimulating. I’ll look him out, especially Insumisos.

Hilary, thanks.

If one single person reads Todorov as a result of my ramblings – I am no expert on Todorov by any means – then I have done much better than I could have expected.

I came to Todorov obliquely, through Spain, and especially his interest in the Spanish painter Francisco de Goya y Lucientes. Todorov’s book on Goya is wonderful. Unfortunately, and inevitably, I don’t think it is translated.

Todorov claims Goya as the great Spanish intellectual of all time, and the maximum expression of the Enlightenment in Spain. We in Scotland, had philosophers, but in Spain, they had Goya.

A painter who did his daily, salaried job which was painting Kings and Queens, and by night, critiquing Spain and Power with his withering etchings of “capricho y invencion”…. one of the greatest geniuses of all time. Not just as a painter. As a thinker…

He died in exile, like most Spanish intellectuals tend to do.

And as the Catalan poet Gil de Biedma wrote, just fifty years ago,,,

Because the history of Spain /

Is the saddest story ever told /

Because it ends badly …

And alas it is true…

Jaime Gil de Biedma (another exile) to the great Gabriel Ferrater, (another great poet; and more than a poet: a hero), in a dedicatory note to a book:

“More than nine years ago – a hell of a lot of time –

In an old country manor while the lingering chime

Of rain was heard outdoors, by the fire we sat.

Lazy, well-fed, indoorish, each other’s best liked cat,

For both of us were in very high spirits,-

Chinchon – a Spanish liqueur – if I recall

We kept playing old lyrics

Sung by Judy Garland, thinking the world was a friend

And talked ourselves to drunkenness without end.

Let them now do the talking, those sons-of-what-we-spoke

Your poems and my poems, our old own private joke!”

Sad to hear of Tzvetan Todorov’s death and it is good that Bella Caledonia pays tribute to his work.

I am surprized that his books ‘Facing the Extremes’ and ‘Hope and Memory’ are not mentioned.

The latter was described by the philosopher John Gray as ‘one of the truly great studies of the twentieth century.’

Look Florian, I am no expert on Todorov. I have read a couple of his books with great enjoyment and I wanted to mention how sad I felt when he died. And I bet I have read more Todorov than you ever have, But along come the fcking Scots to remind how much you don’t know, they never cease to put the dampers on you those loathsome Scots…

Bella Caledonia is a marvelous webpage, which exists because people like me chip in with out scanty and incomplete knowledge. Why don’t you go and fck off and tell us about the great books John Gray talks about?

You embarrass yourself with the comment you made above. I note that you have made similar comments about Fiona Hyslop. I am in exalted company.

Bella Caledonia really must decide if it is a journal for serious discussion of serious issues or not.

Florian, sorry, no offence intended. We all have our days. Barring the New York Times, I don’t think any of the English language press mentioned Todorov’s passing. Which is the point I should have made to you.