Gramsci’s Scotland

‘The old order is dying and the new one is struggling to be born’.

‘The old order is dying and the new one is struggling to be born’.

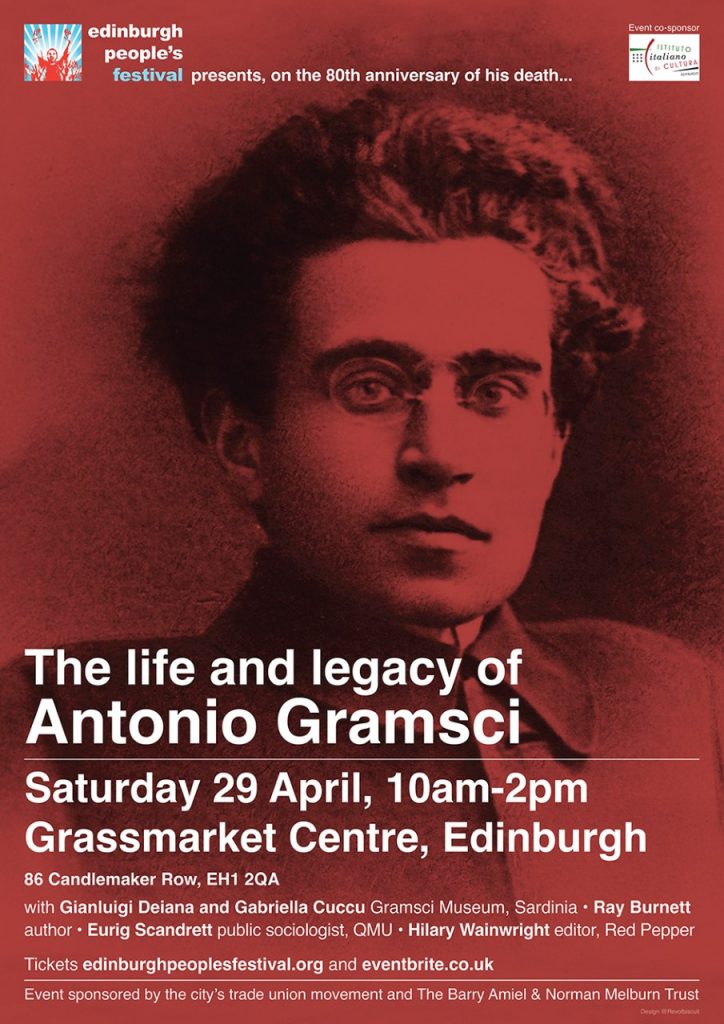

April marks the 80th anniversary of the death of the influential Italian thinker, linguist and Communist revolutionary Antonio Gramsci [1891-1937]. The Edinburgh Peoples Festival, itself a product of Gramsci’s ideas, will mark the occasion with a landmark event* commemorating his life and legacy with speakers from his native Sardinia and from Scotland.

Antonio Gramsci is studied throughout the world as a linguist, sociologist, folklorist, Communist revolutionary and the most distinguished European Marxist thinker since ‘the old man of Trier’ himself. His ‘Prison Notebooks’ provide many original contributions to political theory and contain his thoughts on a wide range of subjects from Italian history, the rise of fascism, the Russian Revolution, popular culture to intellectualism itself.

Born in Ales, Sardinia in 1891 the fourth of seven sons to a local administrator Gramsci suffered many health problems as a child which left him with a pronounced hump. In 1911 he left the island after winning a scholarship to the University of Turin. There he became involved in the working class politics of this burgeoning industrial city. Rising through the embryonic socialist movement he pioneered workers councils as a means of organising in the factories. Inspired by the Russian Revolution he helped establish the Italian Communist Party [PCd’I] in 1921. Spending time in Moscow as the party’s representative on the Comintern he refused to bend to Stalin’s ‘socialism in one country’ dictat and insisted on adapting Leninism to suit specific Western European circumstances. He became leader of the CPd’I in 1924 and led the anti-fascist resistance to Mussolini. Jailed in 1926 despite his purported immunity as a Parliamentary Deputy Gramsci spent the last 11 years of his life in jail enduring great physical pain, severe privations and intellectual isolation.

Mussolini prohibited Gramsci’s political activity insisting famously ‘We must stop this brain from functioning for 20 years.’ He failed however. For in jail Gramsci wrote his enduring ‘PRISON NOTEBOOKS’ which were smuggled out by his sister in law and brother and cover a great swathe of ideas developed during his time in prison. He died in 1937 after his warnings about the longevity of fascism were unfortunately confirmed and thus exposed the Comintern’s disastrous ‘Third Period’ appeasement.

CULTURAL HEGEMONY

Gramsci’s most celebrated work however concerns the perennial question how does a tiny capitalist elite maintain its control over the masses? In his theory of cultural hegemony he argues that states use civic institutions – the media, education, the family, the church, the trade unions, the arts, charities, parliaments etc. – as much as state repression and economic conscription to maintain their authority. This ‘Consented coercion’ as he called it, sees the masses socialised and conditioned to accept their subjugation as ‘common sense’ or ‘normal’.

This view has relevance for the Independence movement in Scotland today as we try to persuade people ours is the ‘normal, ‘common sense’ way of governing and the ‘political union of 4 nations’ is outmoded and absurd. Such challenges to ‘received wisdom’ are typical of Gramsci.

Rejecting the idea that socialism will inevitably rise from the internal contradictions of capitalism Gramsci also believed this view undermined the agency of the working class. ‘If you can blow a raspberry like mine you can start a revolution’ he insisted. ‘What we really are is created from the struggle to be what we want to become’ he said. Rejecting the ‘economic determinism’ of orthodox Marxism Gramsci argued that it diminished the working class’s ability to intervene which was essential for change to occur. And this belief was not just an organisational imperative but an intellectual one.

‘All men [and women] are intellectuals in that they have the capacity to think rationally but not all men have the social function or opportunity to earn a living as intellectuals’ he said stressing the importance of popular workers education to encourage the development of working class intellectuals.

‘I BELONG TO GRAMSCI’ – THE SCOTTISH CONNECTION

Gramsci’s ideas came to Scotland via two men, Hamish Henderson and Tom Nairn. Hamish was an Intelligence Officer during WW2 who saw active service in North Africa and Italy. During the latter campaign he fought alongside Communist Partisans. Through them he encountered the ideas of Gramsci and was inspired by them. Indeed it was Henderson who first translated the ‘Prison Notebooks’ into English. Among the remarkable achievements of Hamish Henderson’s long, creative and distinguished life was his collaboration with Norman and Janey Buchan, Ewan McColl, Joan Littlewood and Martin Milligan to found the Edinburgh People’s Festival in 1951. They incorporated Gramsci’s ideas on folk culture and intellectualism into a distinctly Scottish setting and used them to critique the International Festival itself.

The equally distinguished aesthete, academic and political theorist Tom Nairn came to Gramsci after graduating from Edinburgh University, participating in a famous occupation of Hornsey College of Art in 1970 and moving to the University of Pisa to study. There he encountered Gramsci for the first time and immersed himself within his ideas. As the fates would have it when he returned to Scotland in the late 70’s it was to the same Edinburgh Street as Hamish Henderson. Between them they introduced Gramsci to a new generation of left thinkers. In his book ‘The Enchanted Glass’ Nairn explained how the British people had been conditioned into accepting the monarchy. ‘They wish to be beguiled by Monarchy. It was not merely that monarchies reigned over us – we wanted them too. And found some comfort in it.’ Not since the collapse of the Chartist movement in the 1840’s concludes Nairn has the republican movement been effective in challenging the nonsense inherent in ‘the divine right of Kings’ and ‘hereditary rule’. This ‘pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will’ is one he shares with Gramsci.

*’The Life and Legacy of Antonio Gramsci’ takes place on Saturday 29th April 10am-2pm at The Grassmarket Centre, Candlemaker Row. Tickets are available via Event Brite or via the People’s Festival website www.edinburghpeoplesfestival.org

Gramsci is interesting because he was the first Marxist to really grasp the extent to which capitalism penetrated people’s psyches and I can see why his ideas are potentially relevant.

Yet, his theory of hegemony or false consciousness has always unsettled me; it suggests (arrogantly) that socialists have discovered the ‘truth’ and that the truth is socialism – everything else is false consciousness or common sense. It’s a religious way of looking at the world which is both arrogant and elitist because it suggests that the working class need de-colonised by enlightened socialists.

Gramsci regarded the collective and personal process of searching for the truth as a revolutionary act in itself.

He’s not here to answer the question but I can see nothing his analysis that would have precluded it’s application to progressive cultures and movements. And as a dialectical materialist but opponent of determinism I don’t think he would have written a prescription for the outcome.

But then, is a rejection of socialism a vestige of capitalist hegemony?

How readable is the book The Enchanted Glass by Tom Nairn? Some reviews I read said it was a bit heavy and theory-laden (possibly drawing on Gramsci?).

Interesting article but as a detail I’m not sure the third period of the Comintern can be characterised as one of appeasement.

I understood it to have initially adopted “class against class” an all out rejection of alliance with social democratic movements followed, after the defeat in Spain and Germany by the Popular Front. A switch to seeking a leadership role in broad anti fascist alliances. An approach that Gramsci adopted in Italy.

If appeasement is a reference to the nazi-Soviet pact then fair enough, it was clearly a pragmatic foreign policy rather than an ideological position (combined with more than a vestige of old imperial Russian expansionism). As to “disastrous” who is to say that the timing and strategic impacts didn’t play a role in the Soviet Unon’s later role in Hitler’s defeat.

Before any body says it, that’s not a defence of Stalin, it’s a question about the history of the fight against Facism.