Artwashing and Gentrification

Artists and arts organisations have often engaged with processes of gentrification. Increasingly encouraged by the state into public-private-third sector “partnerships”, many arts organisations and artists have discovered new value in the intangible worlds of “community development” and “community engagement”. Socially engaged art has become a catch-all banner for state and corporate instrumentalism, embracing the rhetoric of inclusion, wellbeing, social impact and social capital in so doing.

I argue that artists are increasingly being instrumentalised by the state, local authorities, corporate interests and financial investors, and third sector organisations eager to promote urban renewal and narrow notions of ‘the civic’.

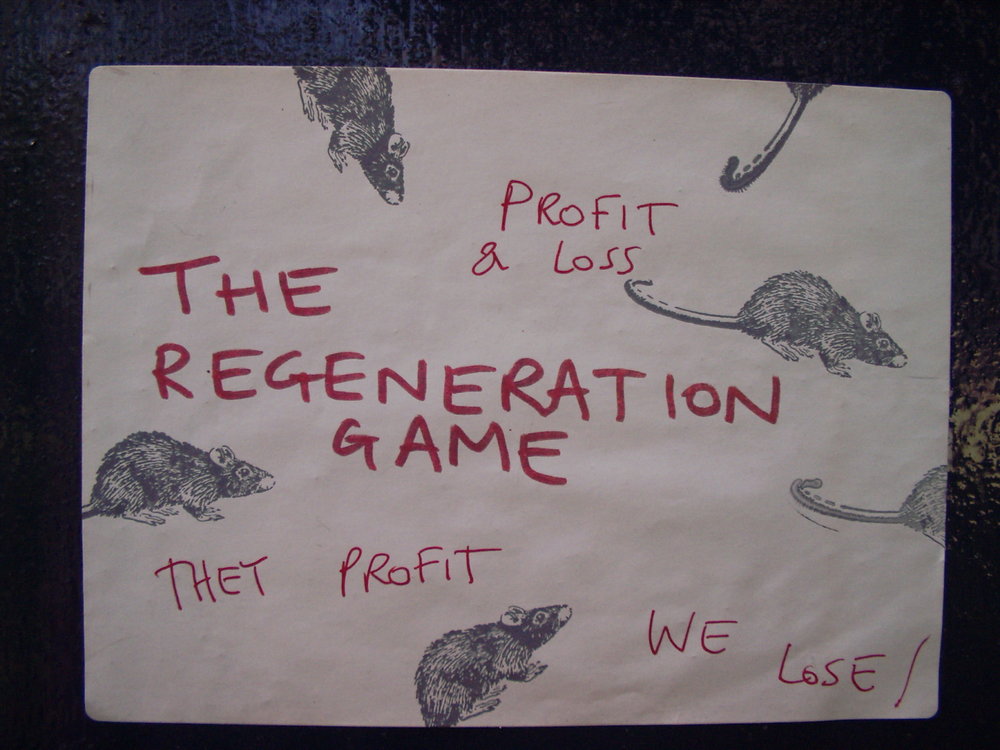

Regeneration. Everyone knows what that is, right? It makes places better. It improves people’s lives. Doesn’t it? I say NO! It is a game. A game played by the privileged; by those in positions of power. The regeneration game, like everything in this neoliberal hegemony, is about capital and profit. It is also about massive human losses.

For urban geographer, Neil Smith, gentrification was a ‘dirty word’, particularly for working-class people whose lives are negated and destroyed by the process and its ‘language of revitalization, recycling, upgrading and renaissance’ (1996, pp. 25-32). Working-class areas become, in the eyes of gentrifiers, barren wildernesses devoid of anything of value or significance, barring a few ‘salvageable’ landmarks that add much needed ‘authenticity’.

Gentrification, like the ideological project of dismantling the welfare state and the privatisation of public services, reveals a constantly shifting and expanding dividing line between haves and have nots. For Smith, this ‘gentrification frontier’ divided ‘areas of disinvestment from areas of reinvestment’ (1996, p. 187).

Yet gentrification has been redefined by many policymakers and planners. Placemaking and artwashing are their tools. Contested issues such as displacement and class relations are brushed away by positive terms such as ‘revitalisation’, ‘renaissance’ and ‘revival’.

But what is artwashing? Artwashing is a simple word. A hook. Artwashing is, however, a complex deception.

Artwashing does not only intend to deceive, it also makes untruthful assertions. Artwashing is nothing short of a breach of trust.

Artwashing uses art to smooth and gloss over social cleansing and gentrification, functioning as ‘social licence’, public relations tool, and a means of pacifying local communities. I argue that artwashing takes several different forms.

First, what I call ‘corporate art washing’.

he classic example of this type of ‘artwash’ involves corporations such as BP and Shell who used artwashing as a form of PR, however, many brands now employ the arts in this way. Artwashing, as activist Mel Evans pointed out, helps cement the corporate ‘social licence to operate’: a fundamental element for many businesses which intends to protect them from less palatable aspects of their business by persuading the public to trust them (2015, pp. 70-84).

Second, ‘developer-led art washing’.

For example, LondoNewcastle – a luxury property developer: a profiteer of gentrification and social cleansing. It adorns its developments with carefully commissioned street art and has its own contemporary art gallery in Whitechapel. Art is here used to promote individuality and luxury to its clients, just like its CGI’s.

The Artworks Elephant is a pop-up boxpark on the site of what was a public space and a playground on the edge of the Heygate Estate. Writer Dan Hancox called it a ‘shiny bauble’ to distract from the ‘social cleansing’ of the area (2014). Shipping containers on community land circumnavigate planning processes. Others wanted allotments, a pond, sports facilities, etc. They got a haven for hipsters that doubles up as a sales office for global developer Lend Lease who are behind the social cleansing of the Heygate Estate! Oh, and a colourful mural remembering the ‘People of Southwark’ now displaced from the area.

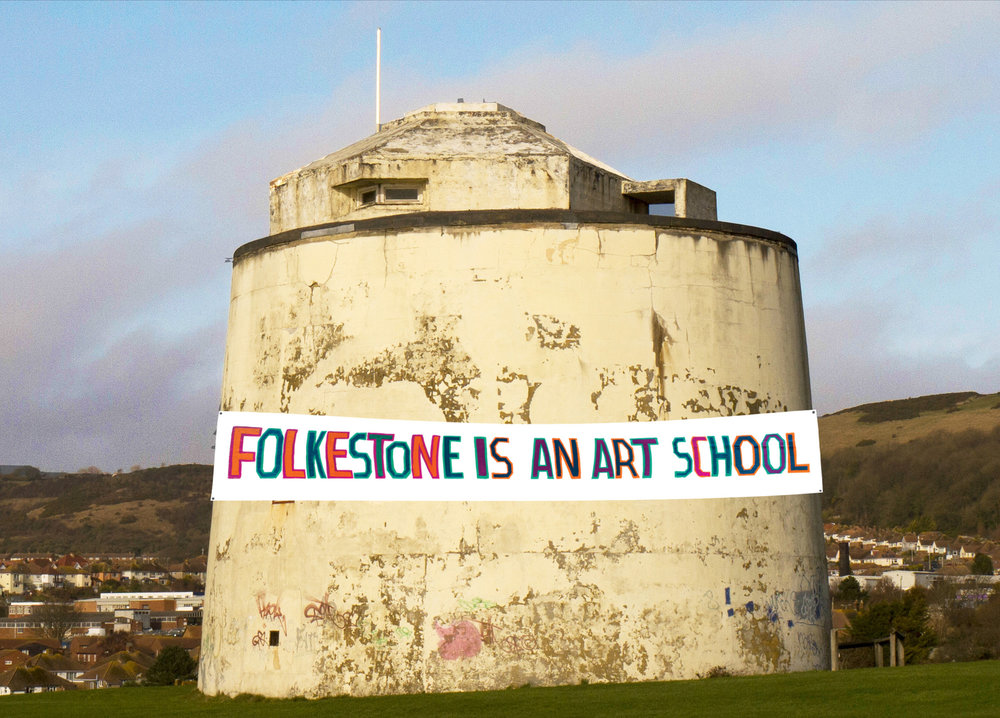

Folkestone is gentrifying – fast. Artists and the town’s cultural quarter often cited as a major driver (Bennett, 2011; Batty, 2016a; Hanson, 2016). People are moving to places such as Margate and Folkestone to escape London’s gentrification-fuelled housing crisis. Folkestone Triennial founder Roger De Haan, the wealthy ex-owner of Saga Holidays, has not only leased almost one hundred properties to cultural organisations and spent more than sixty million pounds on the town’s cultural quarter, but is also planning to build a luxury harbour complete with an expensive new property development. This is art festival as ‘cultural branding’, concealing ‘what is basically a speculative property development aimed at elite consumers’ (Batty, 2016b). Folkestone is gentrifying and, looking at the architect’s CGI images, very white!

Third, ‘local authority-led artwashing’. The realm of ‘old’ and ‘new’ public art.

In 2010, Southwark Council commissioned this film featuring many local arts and cultural organisations. Its imagery is shocking. Scene after scene painting over the Heygate Estate, the Elephant and Castle shopping centre, on and on…

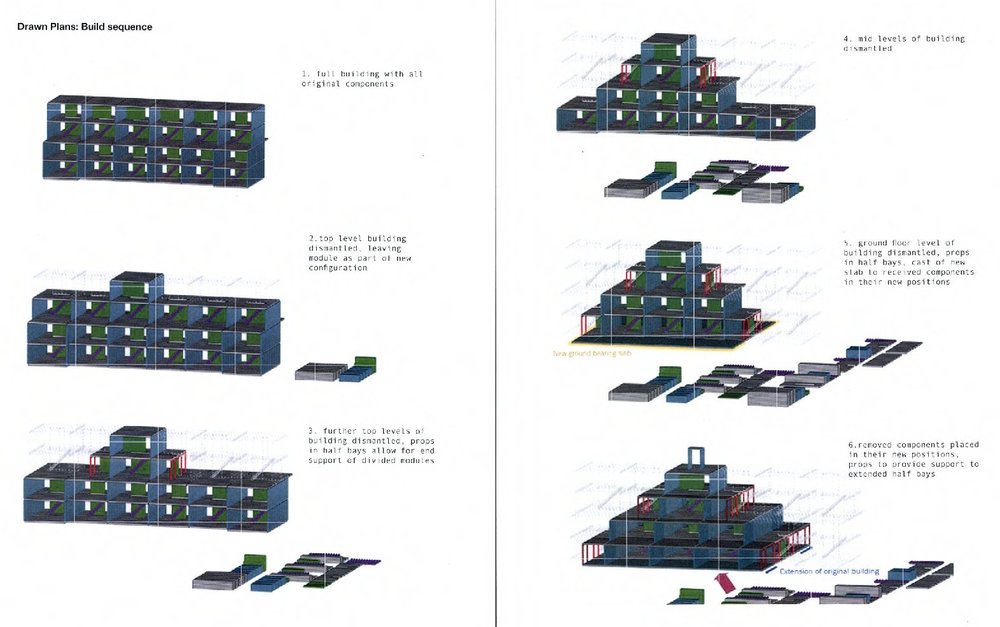

Artangel were commissioned to produce an intervention on the soon-to-be-demolished Heygate Estate. In turn, they commissioned artist Mike Nelson to produce the Heygate ‘pyramid’, constructed by the selective demolition of one of the decanted ex-council housing blocks! Anti-gentrification collective Southwark Notes led the campaign against the public artwork. The campaign was successful and the project was dropped.

Artist Marcus Coates was also commissioned to ‘respond’ to the demolition of the Heygate. He had a vision! His vision. His ritual. A film which functions as an advertisement for the property developers. Local anti-gentrification activists defaced the posters.

Park Fiction, Hamburg. The St. Pauli area of Hamburg has undergone sustained gentrification, turning a decaying, edgy, once working-class, industrial area into an increasingly middle-class one. Artists appeared to be at the forefront of the struggle against gentrification. Park Fiction – emblematic of socially engaged art as enabler of grassroots collective urban planning. This accolade appears debatable, however, because Park Fiction was part of Hamburg city government’s broader regeneration agenda – an agenda that, like so many other cities around the world, fetishised art, culture and commerce. It was, in fact, a testbed for a softer form of state-backed cultural intervention that harnessed the social capital of activists in St. Pauli on behalf of the state, which sought to pacify anti-gentrification protestors. City authorities also funded the construction of the park, giving €2.4 million to the project. Park Fiction is now a popular location: ‘a colourful setting of subcultural chic within the on-going gentrification of St. Pauli’ surrounded by middle-class food places. The park has increased property values, ‘inadvertently supporting’ the very ‘profit-orientated, socially irresponsible redevelopment’ that the activists claimed to oppose (2014, pp. 43-44). Art changed a demand for a park into a Park Fiction, transforming the right to public space into a brand inspired by the postmodern film Pulp Fiction (Czenki & Schäfer, 2001, p. 100).

The lead artist involved in Park Fiction also was a key figure in Hamburg’s Right to the City movement. Its manifesto rejected gentrification. It began: ‘We say: A city is not a brand. A city is not a corporation. A city is a community.’ However, the movement appeared to fight brand with counter-brand; marketing with anti-marketing. They were repeating the narrative that artists are exploited: the ‘city’s unwilling puppets’; inadvertent victims of capitalism. Yet, the squatters and artists were working to support to ongoing gentrification of the city; the contested buildings acting as a ‘beacon to the creative class’ (Oehmke, 2010).

Then, low and behold, the same artist went on to be commissioned by the local authorities to lead PlanBude. A project to redevelop the Esso Houses in the Gängeviertel area that spurned the Not In Our Name movement! Following the now familiar Hamburg formula of participatory planning and collaboration, the artist gathered more than 2,000 responses to the development plans. But, in the end, the ex-social housing blocks will be redeveloped by a consortium of international architects. Art masked a consultative process that pacified local people and tenants before delivering a public-private partnership.

Bristol-based Situations was commissioned to produce a series of projects in in Bjørvika, Oslo’s waterfront area and a contested site of redevelopment and regeneration. FutureFarmers produced Flatbread Society which included crop planting and a mobile bread oven. Situations claimed the project represented ‘a new approach to working with artists in sites of regeneration’ (Situations, 2013b). But Situations was commissioned to provide the ‘curatorial vision for this major site of regeneration’ (Situations, 2016b). The area is also known as Fjord City and is ‘Norway’s largest urban development project’ (Bjørvika Utvikling, 2016). Oslo’s Fjord City regeneration area was funded by Norway’s oil economy and a ‘percent-for-art’ programme (Gardiner, 2015). It is widely acknowledged example of a major state-led gentrification zone in which art, in typical Creative City mould, plays a crucial role (Huse, 2014; Andersen & Røe, 2016).

The fourth type of artwashing is ‘arts-led’.

V22: a company of companies with a not-for-profit strand, several profit-making entities and a head office holding company that sells art and shares and is based in the Isle of Man – a tax haven. V22 take over disused spaces and are presently engaged in ‘saving’ public libraries from closure by turning them into arts-led libraries with studio spaces for artists. V22 are also working in a new facility at the new Silvertown development in London. They have also set up a new company for this venture. But, V22 is ran by a businesswoman and board of businessmen with vast global portfolios of financial investments and holding companies whose other interests span property development, gold and diamond mining, and even uranium extraction. Little wonder then that this artwashing company is registered in the Isle of Man! Shipping containers… You couldn’t make this stuff up!

The fifth and final form of artwashing is what I call ‘community artwashing’ – perhaps the most pernicious, deceitful form of artwashing.

Sticking Together SE17 is a project commissioned by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation to examine the ‘civic role of the arts’. The artists said they wanted to ‘harvest’ the stories of people living in social housing on the Aylesbury estate. But, of course, Sticking Together SE17 did nothing to protest about ongoing social cleansing of residents and produced a series of happy collages that failed to discuss the issues affecting the estate at all.

The People’s Bureau were commissioned by a range of supporters from Tate Modern to the local council to the previous and current developers of Elephant and Castle shopping centre. The artists involved designated it as an ‘opportunity area’. The artists’ ‘fun’ approach and pink market trolley was, of course, featured in the tax-evading property developer’s marketing literature as an example of their community investment and consultation. For good measure and, no doubt, art world validation, the artists took their project to the new Tate Modern extension earlier this year.

Homebaked is an art project-cum-community bakery in the heart of Anfield, Liverpool. It claims to be community-led. Its intention is to rebuild the local community ‘brick by brick and loaf by loaf’. Jeanne van Heeswijk was commissioned to lead the Liverpool Biennial-funded Homebaked project in Anfield, Liverpool. She is a regular on the global biennial circuit; an important socially engaged artist (Creative Time, 2016). As a Community Land Trust, Homebaked’s mission is to provide ‘affordable homes for local people whose needs have not been addressed by conventional development’ (2Up2Down, 2016b).

However, claims that this project was instigated by local people seem to underplay the role of the Liverpool Biennial, ACE, Liverpool Council, URBED and other supporters. Homebaked talk of ‘skills sharing’, ‘capacity building’, ‘CLT strategies’, ‘development’, ‘redevelopment’, ‘regeneration’, ‘affordable housing’, ‘mediators’. They claim to want to avoid becoming ‘agents of gentrification’. But Anfield is gentrifying. Homebaked’s awareness of its potential role in gentrification, together with its art world origins and links to Liverpool Football Club, suggest an intentional strategic use of ‘socially engaged art’ as a means of ‘selling’ communities to possible property developers. Homebaked is perhaps the first example of what could be termed, ‘piewash’! They even cashed in on the recent general election with #PiesForCorbyn!

Turner Prize-winning Assemble. The story goes that Granby 4 Streets CLT happened upon a crazy not-artist/ not-architect collective and began collaborating with them to do up ten houses in Toxteth, Liverpool which, against all understanding and expectations, somehow won the 2015 Turner Prize. That’s the story. Yet the reality is very different. Posh group of mainly ex-Cambridge graduates, Assemble, were commissioned by the Community Land Trust which has a board of senior arts figures and financial investors. They were paid to do the work; to produce designs.

Assemble were not unknown either. Assemble have been commissioned by local councils and other institutions since 2010: the Glasgow Commonwealth Games; RIBA; Create London; arts institutions in the USA; Goldsmiths new art gallery…

Yet the idea that the Turner Prize-winning regeneration project was led by a committed group of community members who had remained in Granby even after the devastation of New Labour’s Pathfinder programme, is unfortunately false. Funding was provided by a secret private investor from Jersey. Steinbeck Studio paid Assemble and gave a £500,000 loan to Granby 4 Streets CLT to ‘lever’ massive funds from Arts Council England and others to enable their 10 houses in the neighbourhood to be refurbished. To enable them to win the Turner Prize. And people from around the world now flock there. The ‘art project’ is nothing more than a massive advertising board. A For Sale sign.

And who’s on the board of Granby 4 Streets CLT, Steinbeck Studio, Homebaked and many more art projects involved in the regeneration of Liverpool and the North West? The same person… The same ‘arty’ people. Like so many places around the globe, THEY are the artwashing mafia!

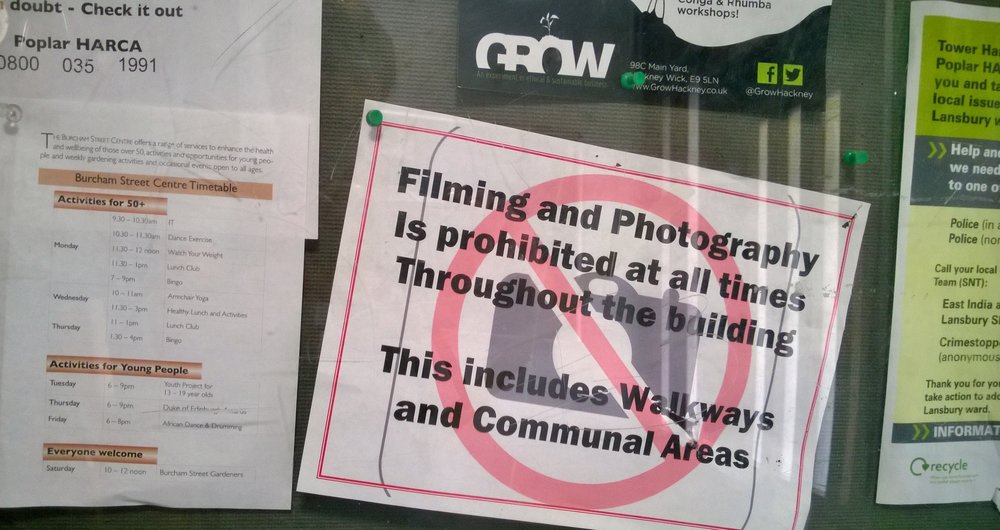

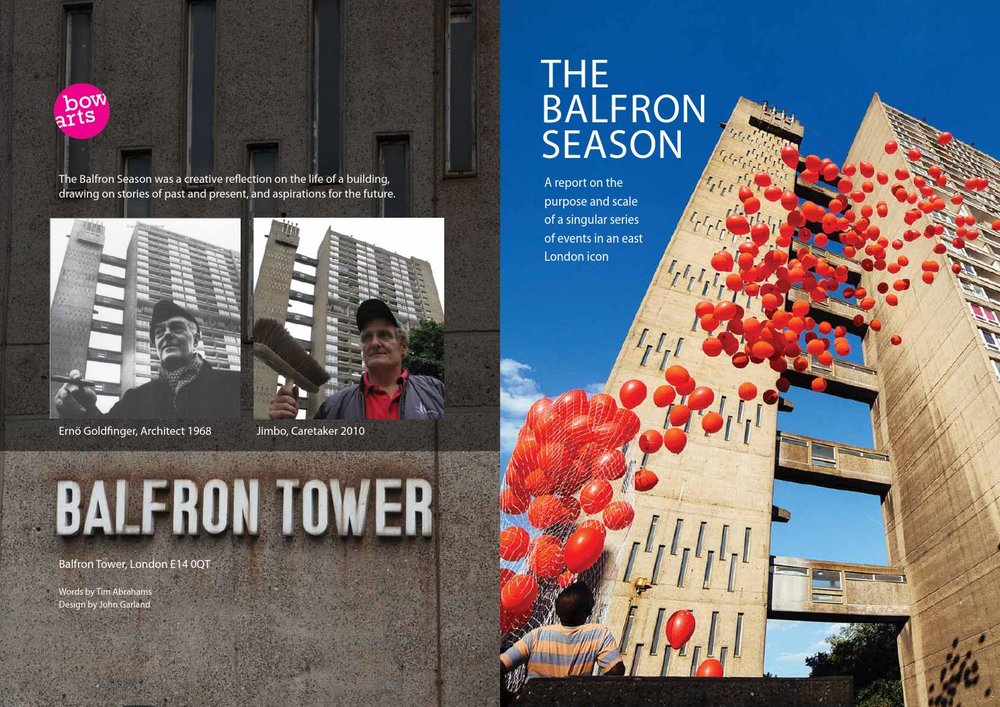

Balfron Social Club is a collective. Residents and artists who resist the social cleansing of iconic Balfron Tower and call out artwashing. They demand 50% social housing in all regeneration projects. For BSC founding member, artist Rab Harling, who was a tenant in Balfron Tower, “art no longer equals freedom of expression, but forced oppression, a violent assault on working class communities by a class of educated and privileged people who choose, in the most part, to turn a blind eye to what is going on, at least until it directly affects them” (2017). He maintains that Bow Arts Trust not only used artists to act as live/work tenants in place of decanted Balfron residents but that they colluded with housing association Poplar HARCA to artwash the social cleansing of the tower. When Harling called them out, challenged them, Bow Arts evicted him.

“Organisations who abuse and exploit artists, that force artists to contribute to processes of artwash on behalf of property developers; that use artists to artwash the social cleansing of social housing need to be exposed. It is time that funding models serve communities and artists, and not just the needs of an arts organisations and their PR machine” (Harling, 2017). Socially engaged artists were, for Balfron Social Club, becoming the scourge of our most vulnerable communities: The “shock troops of gentrification” (Harling, 2017).

Indeed, socially engaged art has become a form of community-consultation-by-art that identifies, gathers, sanitises, archives and exploits the social capital of local people. It operates on the principle of trust. Socially engaged artists are specialists in gaining the trust of community members; more likely to be trusted than business consultants.

A monopoly. Community artwashing exploits working-class people’s hopes and dreams. It ‘harnesses’ them, hope by hope and dream by dream and turns them into saleable, commodified art.

And, like the state-induced notions of “the civic role” and wellbeing, social capital silently turns the benign into the terrible; interpersonal relationships and dynamics into global statistics and generic standards; people reduced to little contributions to the financial bottom line.

Artwashing isn’t about corporate social responsibility or social capital…

Artwashing eats up the lives of those most in need…

Art in the service of gentrification destroys social capital.

Artists, arts organisations and, indeed, art, becomes a pawn in the transnational, multi-scalar world of neoliberalism; of global capitalism. Artwashing exploits by deceit. Artwashing exploits people’s trust.

Brilliant article. Thank you for highlighting this cynical practice.

Thanks Rab. Much appreciated 🙂

I will have to read this again. Resonates strongly downunder too. Another racket. They think them up. That’s what education does? Thanks so much. Great to know there’s a growing resistance.

Hi Fay. Yes. This is a growing phenomenon across the globe. I was at an event about planning in a small town in Durham, UK last week and planners were VERY excited about “using” art to gain community consent. Whilst this doesn’t necessarily amount to artwashing, it is clear that people are increasingly seeing art – and particularly socially engaged art, creative placemaking, etc. – as a tool to further their own agendas. There’s a large and increasing resistance to artwashing in the UK (and elsewhere). What’s the understanding of artwashing and the resistance to it like in Australia?

Classic alt-media critique, just like one could read in “Variant” ten or fifteen years ago. What’s changed? What’s changing? Around 1993, Debord opined that the only change in the spectacle since 1968 was its radical continuity, its radical lack of change. The culturally static nature of gentrification, artwashing and other depressing and banal fixtures of postmodernism confirms this in spades. What artwashing really is is the deployment of Spectacle as a form of social engineering to perpetuate the housing bubble. Turning what urbanists call placemaking into a commodification process. Places aren’t to be made better, they’re to me made more marketable. Which means not just more attractive to buy but more attractive as an investment, ie., more attractive to buy in order to sell.

How much longer can the bubble market in a fundamental need like housing grow along with the idiotic rhetorics of alienated commodity-community? One is a function of the other. The ramifications are large. Gentrification underpins a lot more cultural and political fakery, especially on the left, than even its heavily bought-off leftist critics recognize.

I’m not sure what your target is here Pogliaghi – the left? Variant? Bella? ‘bought-off leftist critics’. the ‘alt-media’?

Hi. Thanks for your comments.

In short, I couldn’t agree more and I’m well aware of the extent to which art is used across the globe as spectacular deceits. My work is also about resistance to artwashing and, like you suggest, I too argue that it is only by rekindling the spirit of Situationism and anti-art, recontextualised for today’s neoliberal assault on our everyday lives, that we can begin to avoid recuperation and fight back against artwashing and the other pernicious uses of art in the name of commodification and reification. My work looks at movements – like Balfron Social Club, Southwark Notes, BHAAAD, and others – which comprise (some) artists and who use their insider knowledge of the artworld to produce anti-art interventions against gentrification.

There are many leftist who’ve been bought, as you say, but I am not one (yet)… 🙂

So glad the writer wrote ‘authentic’ – like so. I hear that word quite a lot, it almost always falls from the sullen lips of middle class artistic types. You used to hear the word ‘gritty’ used a lot an aw.

I used to live off Walworth Road, and i worked for Southwark Council in the Housing Department, back in the day. I was working there when the regeneration project first got off the ground. Some folks in my office often went to meetings, pertaining to compulsory purchase orders and stuff like that. In my opinion no one really gave a damn about the tenants or the leaseholders (I’m not talking about the shady leaseholders who had more than one property, that’s some other RTB shit.) I spent a lot of time in those Council Estates as part of my job and i lived in one. Tough neighborhoods for sure. It could be a bit scary when it got dark. But so diverse and multicultural too.

Even before the plans for regeneration were afoot i knew that the area was gonna be gentrified. From Elephant and Castle to Waterloo, it’s a decent 15 min walk, far too close to the centre of the action to be left to the grubby poor folks of the high rises, flats and council estates. On the first floor of the Shopping Centre they had a display, showing what it would look like when it was all done. A ferry was planned as well, to get more folks across the Thames. There was shenanigans in Highbury and Islington as well that i learned about when i worked in the housing department there. Flush out the poor basically. Course, you never hear that as an official line.

‘Vision Quest – A Ritual for Elephant & Castle 2011’ has 216 views (at time of writing) on youtube. I think some of those folks who say ‘authentic’ and ‘gritty’ are the ones who can write those fantastic funding applications and proposals that preach the gospels of ‘Community Development’, ‘Community Regeneration’, and let’s not forget ‘Community Outreach’. But they’re never around when the beef cooks.

As the sadly departed and much missed Mark E Smith said, ‘the working class have been shafted, so what the fuck you sneering at?’

Hi. Really nice to hear you reflect so deeply in response to the article. Thank you for sharing.

NewcastleGateshead has been boiling my geordie p**s for ages too.

Great article! Thanks.

Cheers Joan. Yeah the Great Exhibition of the North is nothing more than the attempt by Tories to appropriate all our northern cultures (we are not one) and artwash them with weapons-makers and tax avoiders like BAE, Virgin and Accenture. The idea of the Northern Powerhouse is a sham – a divisive sham. Watch out for out Other Great Exhibition of the North which will run in tandem to the “official” festival. One element will be the Great Exhibition of the South – a parody…

Long on critique, short on alternative strategy.

Hello Jim and thanks for your comment. It is long on critique but that’s because it is a critique: an attempt to begin to negate the negation. My work offers alternative strategies too. This article briefly mentions one attempt – that of Balfron Social Club – which offers interesting insight into tactic resistance. There are many others and many more in development. I also believe that it is not my job (at least not alone) to propose an alternative strategy. Rather, I believe that what’s needed is alternative strategies developed by individual communities, groups and movements in response to their own contexts…

“I believe that what’s needed is alternative strategies developed by individual communities, groups and movements in response to their own contexts…” – something like what Homebaked is doing in Anfield then?

You’re obviously much happier sitting in your ivory tower, googling away and ‘critiquing’ a project that has local people at its core rather than take up the repeated offers that have been made to come and see it first hand.

This repeated dissemination of shoddy research is simply rude Stephen – those involved would be more than entitled to tell you to get stuffed if you ever did bother to make the long trip to Liverpool.

Fascinating article. Thank goodness none of that is happening in Scotland. Perhaps this is due to our artists and critics being part of a much more socially engaged culture.

Not happening in Scotland? Really?

Yes really. I’m sure if anything like that was happening we would have seen it covered in Bella Caledonia or elsewhere.

Ah, sorry I was slow to your sarcasm. I’d be very happy to cover it here – in fact that was one of the reasons for asking Stephen to contribute – as he’s one of the leading people who are analysing this phenomenon.

I’d be interested in examples and think that actually some of the early work in Glasgow in the 1990s might well be precursors to what is now termed artwashing. I’m also looking closely at Leith…

Good forensic stuff Stephen and right on the mark. ‘The Arts’ have provided an endless stream of useful idiots for the construction jackals for decades, and Marilyn’s belief that non of this is happening in Scotland is touching, but misplaced. If she were to read the article I wrote in Bella a while back on ‘the golden jobbie’ hotel etc she would find that the plan to desecrate the Royal High School in Edinburgh began as a cutsie little ‘Arts Hotel’ then more than doubled its budget to become an ‘international luxury hotel’, operated by Rosewood, a company registered in Hong-Kong whose CEO lives in New York, while the project is now owned by a US company which, for reasons of tax efficiency, is using a Luxembourg-based subsidiary. There are many other examples. The truth is that the most rancid kind of global capitalism and its construction industry cronies – rather like the BP portrait awards – use the arts as a trojan horse to engineer social cleansing programmes in our city centres. Keep up the good work!

My apologies –

“Revitalising the Old Town, check out Hidden Door Festival, coming soon: http://hiddendoorblog.org”

https://twitter.com/bellacaledonia/status/448383640205287424

and

“The Hidden Door seems to have morphed into something really amazing this year: http://hiddendoorblog.org well done to all behind it”

https://twitter.com/bellacaledonia/status/604243727947800577

Really interesting article, thanks. As an activist, and designer, who works with and in communities, I am however sad to see this lacking examples or strategies going forwards. Some of these artists you have criticised have produced good work, and really we should be challenging the system and motions that put them there. As artists / designers we can resist calls to work in these situations, but we need work, and these opportunities are framed to attract and are exploiting artists in the same way that the artists then end up exploiting the communities they are situated in. I would like to hear more solutions-focused discussion, some strategising, planning, mapping and discussing. What role does (and should) art and The Arts have in and for communities? There is already so much critique out there, what we need to do is move forwards with that, but create at the same time as destroy. There is a lot of ignorance mixed with good will in the Art World, so it’s an important article if it breaks through that a bit. But what about the ‘good’ projects? What about good practice? Maybe we should all be making a whole lot less art and start smashing the system a bit more fully..? RIOT! (Jimmy Caulty’s ADP Riot Tour, 2014) http://www.archive.l-13.org/acatalog/JIMMY-CAUTY-ADP-RIOT-TOUR-.html

Very interesting and necessary article – two points I’d like to make though. You mention that Assemble were paid, as if that were a bad thing and proves that they are sell-outs. But artists must be paid – if not art (as a job, which I believe it should be) is just the area of the privileged who can work for free. An artistic ‘big society’ if you like, where the wealthy get to dabble in their spare time.

Secondly, there is very little money in the charity and community sector so many artists are accepting jobs from the bad guys in order to earn at all. Artists have struggled through austerity too, and many of them have been used by corporate sector as you describe. Art doesn’t stand outside the system, it’s affected by the same dynamics as the rest of our society. Not an excuse by the way- an explanation

Its shame a perfectly decent angry art polemic was undermined by your cherrypicking for effect or argument. I work in Liverpool as an artist – which means I am a community artist and make money running a pub, since I will never make a career out of selling my art. I have been working as a community artist in Liverpool for 35 yrs. Theres a strong ground based and people based art scene here – largely ignored by the larger corporate institutions which hoover up the commissions and lay a patina of art bollox over their patronising efforts when in contact with the residents. To some extent this is good because we are left to our own devices and get on with what we can in these terrible times. Its frustrating because the outside world only see the city (and the larger arts world through the lens of its own middle class preoccupation with ‘curation’ and the language of the gallery. With regard to the 2 projects you talk about in the piece, did you talk to Joe Farrag about his contribution? Or one of the other core members of the black community who have fought for 20+ years to keep the Granby streets and the community around them? Against appalling odds Joe and other friends refused to go down- using art of the people – sometimes crude or ‘unworthy’ almost always un sellable (cos of the site, tools, or the lack of education of the artist) to proclaim and shout about the need for these working class areas to remain and to do so as close to the original occupants and feel as is possible. He loved the Turner cos it gave him a lever and a hammer to make a noise and get more movement on the central project. personally I think its calssic case of a group of outsiders being trusted instead of us local artists, but if they had used us I assume you would never have heard of it. we maybe need these underwhelming london centric artkiddies with their jargon and battery of appropriate language and gallery guides to attract the tv and the politicians because you know we who work here know nothing apparently. But we will fight for our art and for the power it gives, we will use what we can, and sometime we have to take money from the developers and builders, the same old gangsters who have funded art from the beginning – it feels more honest than using the ‘filter’ orgs – at least we take the tainted dosh from their own hands instead of ‘purified’ by the likes of the Tates and Turners (they give us the tiny scraps btw). Granby continues long after the folks from outside have gone. Joe runs a market every month full of art as well as food and 2nd hand and clothes and the things of life. The tragedy is that even with a recognition of this it has to be said that there is little desire from the people to return to a fiction of a rosy working class world – cos without the manufacturing base or docks we have no mass work to be done, our kids work in telesales or KFC, the honest comes form the building sites that destroy our neighbourhoods and thats only temporary. So forgive us provincials if we take the bloodtainted cash for a mural – it pays the rent. Change the system 1st (and were trying to do that up here too) then the art will follow! (ps if you want some horror stories about the way the artworld you are part of misuses communities and the people in them for personal or corporate glory, boy you should come to Liverpool) and chk out Baltic Green in the triangle our small attempt to do rather than talk or pontificate – with money from wherever we can get it…