The Planes will Be Grounded Anyway: Brexit, Climate Change and the Power of Disruption

As the moment when both climate change and the true cringing absurdity of Brexit became tangible and unavoidable – the summer of 2018 seems weighted with an unusual significance.

As the moment when both climate change and the true cringing absurdity of Brexit became tangible and unavoidable – the summer of 2018 seems weighted with an unusual significance.

Both the freak weather and the daily diet of freak politics are, surely, coincidental. They will sit side-by-side in the history books, colouring the way in which both distinct stories are told. The extreme temperature, and its sickening sense of clammy fragility and listlessness, serves as a grim backdrop to a cloying and pervasive sense of national shame.

But perhaps the heat is more of a protagonist than we care to admit. After all, what is Brexit, if not some eccentric rehearsal for the far greater acts of withdrawal, retreat and uncoupling that, based on current trajectories, will mark the decades to come, as the mercury gets ever higher?

Epochal historic shifts of the kind that we are witnessing create impacts that spin off into countless unknowable consequences as they unfold. The current preeminent existential threat (alongside technological and demographic trends) is not a matter for tomorrow, it seeps into every crevice of the structures that run our societies, as though there is something in the water.

But the harshest truth about climate change, seldom voiced, is that such a vast process cannot, deep down, be met with a rational response. Brexit may well be seen as one of the first definitive instances of this unspeakable anxiety taking root.

The far-right, emboldened, squealing in excitement, understand this. They smell an opportunity in the sickly sweet stench of the uncanny heat. Deftly, they channel the general sense of existential threat into xenophobia, archaic notions of national sovereignty, and a grand battle to protect western civilization and individualism.

Build a wall, cage a child: these brutal public sports of an emergent hyper-connected fascism are rooted in fear: a desire to protect yourself and your own from the rising tides of biblical disaster. But such acts, though viscerally cruel and immoral, broadcast a message of necessity.

Why? Perhaps the answer is that most disturbing and revealing fact of all: above all, daily life must go on, even as the news anchor’s intonation gets incrementally more fateful.

When Swedish student Elin Ersson recently interrupted a plane taking off with moving moral courage, many simply sighed at an inconvenient start to their package holiday. These global problems of climate and displacement are too great to comprehend, and so we double down on the comfort of things trundling on, and the hope that the unprecedented standard of living enjoyed by a critical mass in Europe and North America might somehow emerge undisturbed from cataclysm. Brutality at the border becomes a necessary price to pay for this way of life, and as the conditions start to fray at the edges, this is simply becoming more explicit and unavoidable.

The emergence of this “new normal” is premised on a lack of agency (something that has, confusingly, coincided with unprecedented opportunities to voice protest). Its slogan “do not disturb,” contains a horror at the idea of everything grinding to a halt and remains stubbornly ingrained.

Meanwhile, though the UK left has managed to renew itself in the context of general disruption, it has shown itself entirely unable to put a stop to anything. The dignity of labour, linked to the power to withdraw it – to stop the deadly machines of capital from operating – was ditched as outmoded (just as the current ideology became the only game in town) and lacks a social basis for revival.

We cannot comprehend a meaningful pause in the great mesh of networks that help drive the growth cooking the Northern Hemisphere. As distinct units within these networks, we can neither stand outside them, nor pay heed to what they plough under. Climate change has already killed untold numbers, including those resting at the bottom of the Mediterranean. From across the wall between the poor south and the rich north, their silence is too total. Within the wall, beach tourism goes on, as it must.

Yet for all the high-frequency transnational buzz – tourism, finance, culture – physical borders are coming under more strain as the world is on the move again, just as the stability of the homeland itself, its coastlines, its glaciers – all that was supposed to be fixed – becomes porous. Britain might lose great chunks of fertile East Anglia to the briny swell, but she will go to unprecedented lengths to make sure the rest of the land is not tilled by those bearing the stain of otherness.

Build a fence, create a grim gladiatorial arena of murderous exclusion to soothe those who know deep down that even native ground is no longer certain. This is the world we already inhabit, the pictures are readily available for anyone who cares to look. The fence is everything. To even walk too close if you’re on the wrong side is lethal, no one over there can ever be an innocent.

This is not a rational response to the challenges of the 21st century, but it taps into the notion of a great historic drama, where convictions will be tested, weathered, and perhaps triumph. It is the paintings of Rorke’s Drift or Custer’s Last Stand, re-animated with different actors but the same core imperative.

The right’s growing strength stems from this simple notion, its willingness to talk of a great existential threat and offer cathartic linear solutions. Bannon’s new pan-European project is built on one core assurance. Pull up the drawbridge, take back your pride, and turn inclusion/exclusion into the only potent political act.

Societies can be plunged into chaos by little more than the rumour of that which they cannot comprehend. In response they often offer up a whole series of weird and wonderful undertakings.

Individuals, faced with extreme stress and crisis, will often assert control in minor but decisive ways. Say, adopting a rigorous dieting regime, as though that demonstration of will can somehow ward off the intolerable stresses of overwork, cancer, or a death in the family, the unstoppable changes that we all grapple with.

So we find ourselves in a Brexit Britain gearing up for its bizarre ritual response to more apocalyptic times ahead. Its intent; a radical cutting off; its symptoms; wartime measures such as the stockpiling of food; and its rhetoric of red-lines and heroic last stands, are not just echoes of the past. They are a localised version of how global capitalism will come crashing down around us when it has failed to curb its voracious trajectory.

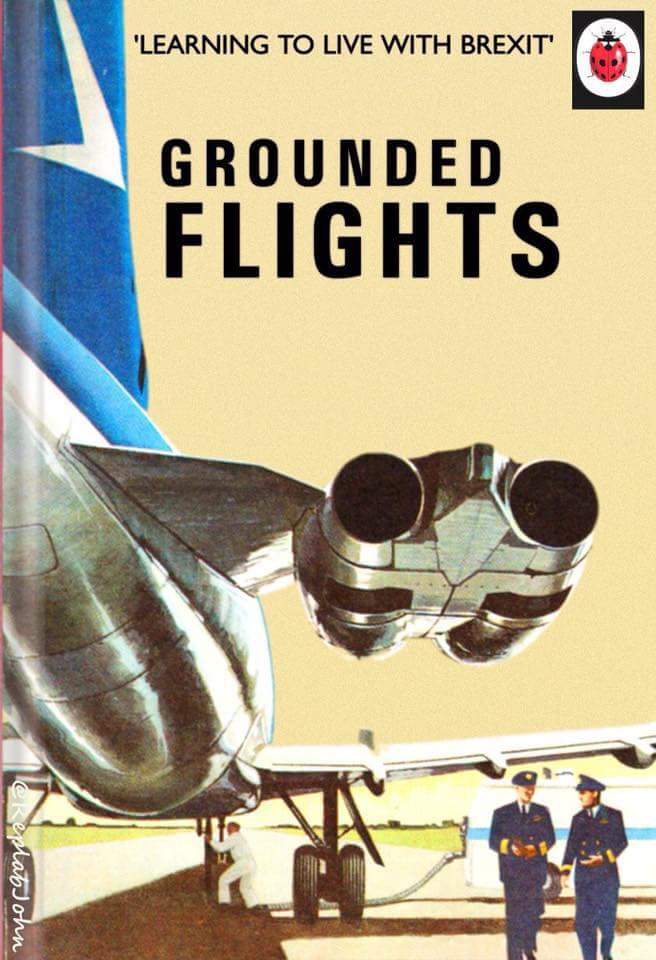

Daily life goes on. But if the planes will be grounded anyway, why not keep them on the tarmac in the name of human decency?

Brexit has demonstrated that, whatever its potential strength and capacity for mobilisation, the left cannot profit from someone else’s act of disruption. Instead, it must rediscover the popular legitimacy of halting participation in ever more perverse versions of normality.

Because when we consider the increasingly locked-in destructive rationale of carbon capitalism, our response to it can no longer be level headed. An old slogan – “socialism or barbarism” might suffice.

Something is needed to generate action in response to the great crime that is being perpetrated now and upon all generations to come. It forms part of a long line of larceny that began with enclosure and the great traumas of the early industrial era, that neutered the rights won in the last century and rendered the collective struggle of workers alien and illegitimate. Today it is staging the greatest crime imaginable – the wholesale destruction of a shared future.

Excellent and sobering article, thank you

I think that vast processes can be met with a rational response, for example the reasons that mythic Noah built the ark are clear. It is just that culturally the UK seems to have difficulty even with cold conditions in winter, leaves in autumn, heat in summer and rain in spring. There even seems to be a perverse pleasure in failing to cope with everyday weather, so I am not surprised that climate change is an order of magnitude too high for some.

The question of whether there a sense of inferiority behind this urge for withdrawal may be tested by responses to familiar cultural competitions. A modern space race might see Chinese people first on Mars, or perhaps the first settled moonbase staffed by the Indian space agency. Brazil or Bangladesh might build the first undersea city, and Japanese robots might win the first android world cup. The sense that some UK politicians seem to burnish their classical education as if their claim to be annointed heirs of ancient civilizations were the finest credentials for modern government suggests a backward-looking mindset rejecting the arena of innovation, global collaboration and improving social and environmental policy and practice.

What has the UK done for the world recently?