The Silent Poetry of Brexit

So what has changed? Well, a lot of the writers who were active in the devolution and independence campaigns of the recent past are older. Some are disillusioned. Some are dead. The new generation of poets coming through have a different relationship with the public and with technology, its value, what it is for and how to use it than, for example, the generation of William McIlvanney. They also, as far as I can see, have a different concept of what the function of the writer is in a place like Scotland and a more relaxed and concurrently disengaged attitude to what exactly constitutes a nation in the first place, if they ever consider it at all. Then there is the relationship technology has to the language the new young writers use, cast as it often is within the limitations of twitter-speak and media-savvy argot. This is not a criticism, just an observation. Every writer in every epoch is both constrained and liberated by the language they use so there is nothing especially new in all of this. Language comes from the history of our human desires and achievements, it moves through the perennial now of the moment, our conflicts and resolutions, changing as it does so and moves off, inevitably, into the future and our imagination. Whether you are wrestling with an ink block in the 15th century or a 5G phone in the 21st as a poet your relationship with language is the same. Your obligation to its furtherance is the same. Your facility to enhance its beauty and add to its stock is the same. The dialectical juggling act of subject and object is the same. The writers relationship with language remains constant because the observational nature of the literary arts remains constant. Our use of language is our societal report. It is not a codicil, but central to the subject observed.

Prizes, fellowships, residencies, bursaries and all the tardy gamut of baubles and awards – this, it could be argued, is what ruins writers, what draws them in. These are the siren songs of the British State. It creates an atmosphere of competition and rivalry and keeps the literary lions tame. Categories, genders, fads movements, trends, profiles, celebrity and all the formal tangential picnics consumerism demands contemporary writers indulge in in order to be heard kills off their radical edge at the click of a mouse. Add to this the proliferation of “creative writing” degrees, of all sorts, which are a feature of almost all universities, and which churn out writers who have “expectations” and a business and marketing plan, but are shorn of the thirst for revolution, then one can see how the dismal process of poetic emasculation goes on. This would explain, if anything can, why – as the Brexit charabanc drags us into what Brecht called “the dark times”, as liberal democracy and laissez-faire capitalism falls apart – the poets are silent. In Scotland it is palpable, like the stillness after a heavy fall of snow.

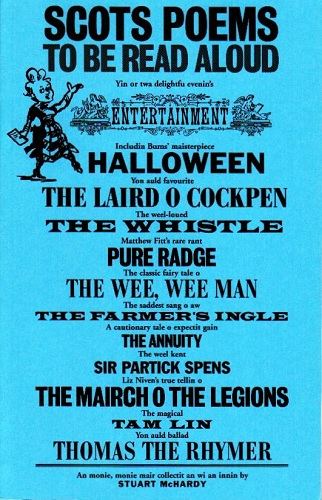

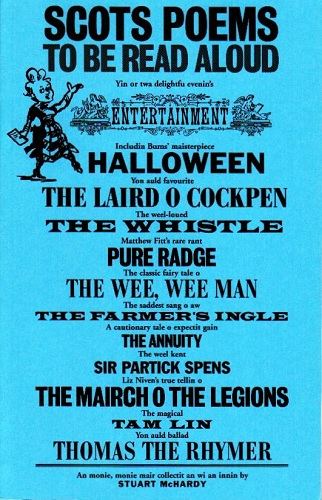

It is not romantic (is it?) to reiterate that in the 1990’s, in the run up to the establishment of the Scottish Parliament in 1999, it was the writers who kept the dream of Scottish self-determination alive in the public mind. All throughout the 2014 campaign for Scottish independence, culminating in the referendum of September, on stages, in community centres and village halls and other public spaces, poets read their hymns to the aspiration of Yes from Wick to Wigton, to large audiences who drank them down in order to sustain their fire. I was involved in a lot of that, mostly in the Highlands and Islands, so I remember it well. 2014 is the only time I have had a play at the Edinburgh Festival more or less sold out for its entire run before the first performance. So is it unfair, unhelpful, to compare then to now? Is it just a given that absolutely everything now, including poetry, has been commodified? Here again we must look at technology and embrace, as best we can, the contradictions.

Things change and the old get left behind. That is just one of the rough facts of existence. Experience teaches that it is almost impossible for the generation born after 1950 to keep up technologically, even emotionally (never mind socially), with those born after 2000. Even those with the biggest hearts and the most open minds get trampled into the pixelated dust of the constant digital stampede. It takes a brave sixty-something year old to say that this is not all bad. Even if you think it is all happening in a parallel universe. Even if what passes for evidence counters everything you believe. Am I just looking in the wrong places for poems to reassure me that the world is not about to end? It would appear so.

According to Andre Breedt, of the UK book sales monitor Nielson BookScan, there is a passion for politics, particularly among teenagers and young millennials which is fuelling a dramatic growth in the popularity of poetry, with sales of poetry books hitting an all-time high in 2018. Is this just the youth equivalent of the “Great British Bake-off” or “The Great British Sewing Bee” TV programmes, that indicate that in times of social stress the best thing to do is to return to the 1940’s? Seemingly not. Statistics from Nielsen BookScan show that poetry book sales grew by just over 12% last year, for the second year in a row. In total, 1.3m volumes of poetry were sold in 2018, adding up to £12.3m in sales, a rise of £1.3m on 2017. Two-thirds of buyers were younger than 34 and 41% were aged 13 to 22, with teenage girls and young women identified as the biggest consumers last year.

Andre Breedt said that sales were booming because in times of political upheaval and uncertainty, people turn to poems to make sense of the world: “Poetry is resonating with people who are looking for understanding. It is a really good way to explore complex, difficult emotions and uncertainty,” he said. This is where digital technology comes into its own because Andre Breedt added that the form’s brevity also meant it could be easily consumed on phones and shared on social media.

“Social media and technology have made poetry much easier to access and pass along, magnifying its impact. To me, it’s no coincidence that poetry as a form is being used to critically discuss events like Grenfell, the Manchester bombing and Brexit as well. It’s being repurposed as this really dynamic and vital form that can capture, in a very condensed way, the turbulent nature of contemporary society – and give us the space to struggle with our desire to understand and negotiate a lot of what is going on at the moment. Poetry as a form can capture the immediate responses of people to divisive and controversial current events. It questions who has the authority to put their narrative forward, when it is written by people who don’t otherwise hold this power. Writing poetry and sharing it in this context is a radical event, an act of resistance to encourage other people to come round to your perspective. The one great advantage we have now is the speed at which we can share new work.”

Such optimism and positivity is humbling. As we struggle in Scotland to organise our future freedom, which will emerge (I have no doubt) from the wreckage of Brexit and the result of the inevitable second referendum on independence, or however we achieve independence, is the dull unmemorable language of politicians we are constantly being subjected to being recycled and made joyously anew by our poets, our new young poets? For we cannot be content with the forgettable utterances of delusional Tories or even managerialist Scottish Nationalists. This is not the music of the moment that we need. We must cultivate a hunger for a more memorable, lyrical language of liberation. You may not be all that impressed with the utterances of contemporary poetry and you may be even less than impressed by its aesthetics, or you may even be exasperated at the laborious attempts to harness half formed feelings which have not yet grown into thoughts, but we must demand that our poets give us the poems we need to move forward beyond expressiveness, and we must be optimistic that they can and will.

As Bertolt Brecht put it in “Poetry and Context” (1940),

“Poetry is never mere expression. The absorption of a poem is an operation of the same order as seeing and hearing, i.e. something a great deal less passive. Writing poetry has to be viewed as a human activity, a social function of a wholly contradictory and alterable kind, conditioned by history and in turn conditioning it. It is the difference between ‘mirroring’ and ‘holding up a mirror’.”

History in the main is made up, despite the big events, from seemingly ephemeral moments which are usually deeply local. These are the contradictions and alterations Brecht was alluding to. In an interview with the University of Colorado, just after his seminal anthology “Radical Renfrew” was published in 1990, the late great Tom Leonard said,

“The structural institutions, the competition for grades, prizes or scholarships by students writing essays on literature for examiners, is all opposed to the very nature of what literature actually is. Such practice turns the living dialogue between writer and reader into a thing, a commodity to be offered in return for a bill of exchange, the certificate or ‘mark’. But no caste has the right to possess bills of exchange on the dialogue between one human being and another.”

One cannot help but think that the flowering of poetry in the cybersphere is just another “commodity to be offered in return for a bill of exchange”? Let us not forget where we are and where we, as a people and a polity, are drifting towards, which is a needless unknown, courtesy of the Tory Party and the currently feckless Labour Party. So where is the poetry which challenges the right-wing coup that is Brexit? Where are the Scottish poets who are attempting to lance the suppurating boil which is the neo-liberal elite? Where are the poems which celebrate the Welfare State and protect workers rights, which warn us about trashing human rights and the natural world? Where are the sublime verses which show up the famine road which is the British No Deal exit from the European Union and which leads to martial law? Am I demanding too much of our poets? I cannot afford to believe that I am for I cannot bear the silence.

©George Gunn 2019

George Gunn’s “After The Rain: New and Selected Poems” is available from Kennedy & Boyd, ISBN 978-1-84921-171-0- 9000

I think, like with climate change, it is the rate of change that is causing the silence.

The articulate simply cannot keep up, both nature and Brexit are changing so fast that it’s not easy to gather the threads needed for an artistic or intellectual response. Whilst you’re working on that one, something else incredibly threatening happens, flooring the senses and demanding it’s own internal response. By the time you’re halfway through processing that bit, another bit comes along and floors the cranium again.

In the case of Brexit the rate of change of stupidity is directly proportional to the rate of change of the climate.

And for the inarticulate, this rate of change merely reinforces their raucaus demand for more fascism or more neo-liberalism (depending on who they are), as if more of what we’ve had before will suddenly make things better. Which the MSM lap up in their churnalism that poses as informed debate.

Listening to & reading Jem Bendell a lot at the moment, on Deep Adaptation, it is clear it a whole series of different debates we need to be having as individuals and societies. Perhaps, then, the creatives out there feel this, even if only subconsciously, and that Brexit becomes a “meh” mask that is covering the real anquish.

Hot off the press.

https://www.theguardian.com/us

Fake news.! The Guardian ought to be ashamed. Questionable whether the pope is still required.

face pigeon shit

face twitter shit

book trivago

fly-be

be

be

be

be

be

(hi digger)

bbc betwatted

Oz@48degree

please RT

Aye.

T’would make you cry.

Bye.

I like that ‘t’would’ – proper poetic.

Here’s my latest, even worse than the first:

Capitalism is shite the world over

Capitalism shites over the world

Capitalism is over (happy emoji)

So is life (sad)

Woah, hang on a minute. Shouldn’t that be ‘twould. I demand a re-write.

We are here, in groups, in homes, on Facebook pages, on blogs, in our own social media pages providing daily updates for others who are struggling to keep up with the pace of change,. We have jobs, children, activism, community stuff to DO.

But we are here

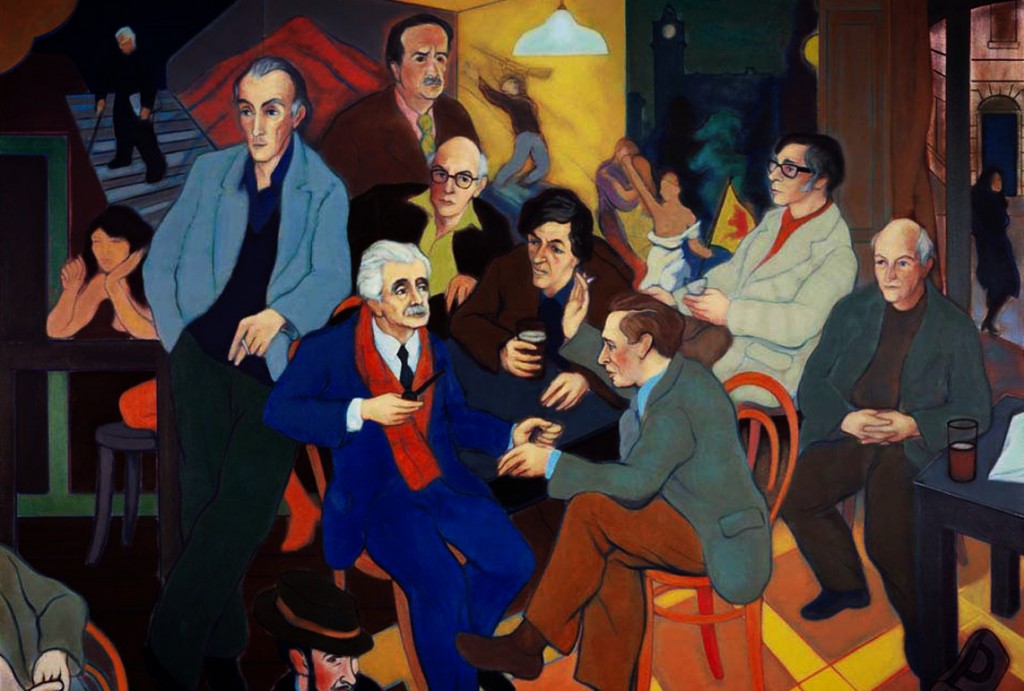

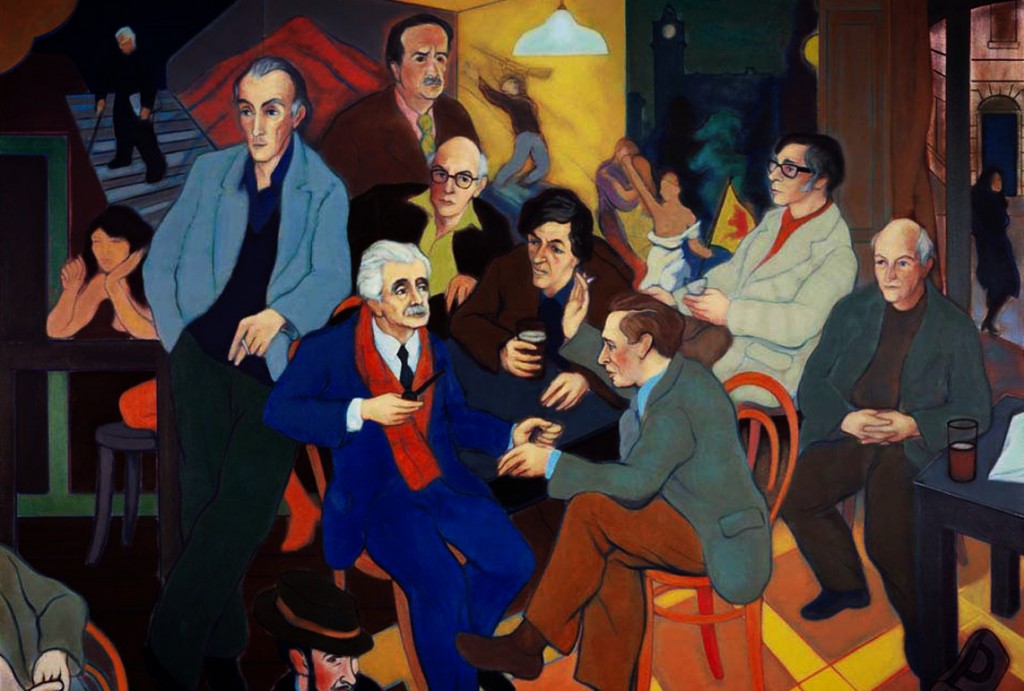

As one of the older types you mention I can see and agree with you, but I tend to see a whole swathe of younger people, not just poets who seem detatched. I am out of touch with who these modern poets are or their worth so tend to fall back on ones I rubbed shoulders with in the late sixties and seventies, Sorley MacLean ,Norman McCaig, Alan Bold and always going back to ,when I have the time A Drunk Man looking at his thistle, you know who I mean.

Exhaustion, yes. A need to re-charge and re-tool, which takes a while. Also a profound distrust of ‘issue led’ poetry. There is a genuine question about what Seamus Heaney called the ‘redress of poetry’. Can poetry really be it a counter-balance – a feather-weight song against a ton of noise? Or must poetry be recruited by some cause of other, and the poets blamed when (radical!) they refuse to engage on those terms. I think about these things often. But I must say this: I have taught ‘creative writing’ at university for nigh on 20 years and have NEVER ‘churned out’ anyone; much less with a business and marketing plan. This is simply not what happens. We have committed, engaged, questing students of all ages seeking to find ways of shaping deep thought and fresh perception into creative expression, so they, and we, can live meaningful and fulfilled lives, despite the howling nonsense around us.

Through Brexit storms

Cabinet un-shipshaped

– all at seaborne.

Bordering lunacy

In contempt

Incompetent

Stop! Back!

Don’t make amendments

Make amends

“There are blows in life, so hard, I don’t know!

Blows like God’s hatred itself which makes

the hangover of everything suffered

well up in the soul. I just don’t know!

They are few, but they are enough.

They open dark furrows in the fiercest face and the strongest back

Could be they’re the colts of barbarous Atilas;

Or maybe the black heralds sent by Death.

…

There are blows in life, so hard.

I just don’t know!”

(“The Black Heralds / Cesar Vallejo)

HMS Distress

In Brexit storms

the Cabinet unshipshaped

– all at seaborne.

Bordering on lunacy

incompetent, in contempt

In Brexit acid constitutional bonds dissolve

– and Scots can knots untie.

We’re not going anywhere

but sailing away

sailing away

HMS Distress

In Brexit storms

the Cabinet unshipshaped

– all at seaborne.

Bordering on lunacy

Incompetent, in contempt.

In Fascist acid, bonds dissolve

– and Scots can knots untie.

Haunted Albion, unmoored

drifting away

drifting away

HMS Distress

In Brexit storms

the Cabinet unshipshaped

– all at seaborne.

Bordering on mutiny,

incompetent, in contempt.

In Brexit storms

all bonds strain

– but Scots can knots untie.

England – haunted, unmoored

drifts off

dreaming of Unicorns and trade winds.

George Gunn has major points to make. I’m glad for the lyricisim of his prose, & see his recent series of essays for Bella as among the best writing on the Silent Poetry of Brexit. I back his attack on the accentuated commodification of poetry, & have sympathy for his swipe at Creative Writing degree courses. Kathleen Jamie’s defense of these is reasonable, & yet still inadequate: “We have committed, engaged, questing students of all ages seeking to find ways of shaping deep thought and fresh perception into creative expression, so they, and we, can live meaningful and fulfilled lives”. The implication is that students, “they” the students learn how to write poetry & prose primarily to make themselves feel better/fulfilled, & that “we”, the future readers, are of secondary importance. But George, drawing from Brecht, is more ambitious about what poetry written in Scotland in the recent past has achieved, & what it could go onto achieve again: is should want to not merely write “meaningfully” about reality, but also to contribute to changing it.

Kathleen Jamie’s “profound mistrust” of issue-led poetry is surely born out of poems many of us have experienced — Carol Ann Duffy has written issue-led poems that are among her worst — yet there are enough counter-examples to prompt good poets into writing about issues. Don Paterson’s “To Dundee City Council” (2015), where he attacks municipal ignorance of beautiful civic architechture, is one such example. The issue-led poem “Spain” (c.1937) by Auden is one the poet thought had so much wrong with it that he distanced himself from it publicly; I’d much rather read that then poetry that could “fulfil” me; and there must be a further category of poem, as much issue-leading as issue-led, which gives propogandistic tosh a wide berth. In this category falls the just-published, magnificent “American Standard” by Paul Muldoon, with a full free audio version read by the virtuoso Lisa Dwan. (https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/public/american-standard-paul-muldoon-poem/) No poet here would be interested in imitating that example, but it shows what epic-political-public poetry can do. Will our poets really stay silent on Brexit? My gut feeling says they won’t; I’m hoping it’s just a delay, before great things can be coughed up. @ George Gunn: are you still sending out review copies of “After The Rain: New and Selected Poems” to people with a serious intent of reviewing the book? @Mathew: you hog the thread. That’s not fair. Bit like bursting in steaming into a pub where people are enjoying accomplished musicians doing a good set, grabbing the mic, and bellowing out an out of tune “Wonderwall”. Your last version of HMS Distress isn’t that bad. But the syntatical inversion in “and Scots can knots untie” lets the poem down, pulling it, at least for that line, into the bad part of the poetical 19th C. Is that the effect you want?

Computer programming combined with the Internet produced a vast open source movement where demonstrating ownership or authorship of lines of code is not the point of publishing them. Perhaps poetry may return to its open source roots. Perhaps vast algorithmic output by artificial intelligences will commodify all but the most specialized human efforts. Perhaps poetry generated on the fly to give dialogue to computer game characters will set a technical standard beyond most professionals.

Perhaps poets trying to own a Brexit poem, where the phrases have already been generated amongst the big data of columns, soundbites and comments could be migrating into a hostile environment, attempting to take control that never was theirs in the first place, claiming they invented everything, smacking of protectionism, crossing one border too far, planting a colonial flag.

Perhaps poets generally know better, that they have not really anything more to say that the public has not already said. Perhaps we are all poets. With the freedom to move.