The Cultural Cringe

Colin Burnett on the origins and power dynamics of cultural self-hatred and insecurity. Read more of his writing here.

Colin Burnett on the origins and power dynamics of cultural self-hatred and insecurity. Read more of his writing here.

The Scottish Cringe as described by Beveridge and Turnbull (1989) refers to the Scots lacking personal and political confidence in their ability to govern themselves. Beveridge and Turnbull (1989) argue the Scots suffer from a sense of psychological inferiority in which Scots have come to see themselves and they are seen by England i.e. as being inferior to and dependent upon the largesse of England. Sociological theorist Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic violence can be deployed as another means to understand Scotland’s sense of culture inferiority because this notion of Bourdieu is used to explain how the more powerful are able to structure the self-perception of the weak, so that social groups are not only conquered or colonised militarily by a more powerful nation as there is another defeat or war waged that is done via or by culture (Bourdieu and Waquarant 1992) i.e. Scots collude in and co–produce their subordination because they sincerely believe their culture is not equal to that of England. On this matter, Carol Craig (2003) argues that Scots are harshly disparaging to their own culture and by doing so create apprehension in the Scottish persona.

Another key term utilised by Bourdieu (1979) is the concept of habitus that describes how and why people become subdued by social conditions and exercise amor fati (‘love of fate’)rather than rebel against their subordination because their habitus aligns the agent with his objective possibilities and so his subjectivity ‘falls into line’ with their objective life possibilities; so, that rebellion becomes an unrealistic course of action. In this regard, Beveridge and Turnbull (1989) applied Franz Fanon’s (1967) notion of inferiorisation in Third World nations to the Scottish context to highlight Scotland’s self-colonisation. Through the lens of Fanon, then, inferiorism is the processes in which the indigenous population comes to internalise the dominant culture or narrative of the coloniser at the expense of their own native, local, traditional culture.

For Fanon, to effectively penetrate another culture and to colonise another population’s self-consciousness, their history must be revised to mirror the point of view of the oppressor. On this point, Billy Kay, a renowned advocate of Scottish culture, recalls how the Scots were not taught Scottish history prior to the Act of Union (1707) as this would mean a ‘return of the repressed’ (Robinson 2008). The idea of repressing the events of Scottish history prior to 1707 seems to corroborate Fanon’s idea of inferiorism as this practice has become so entrenched in the Scottish psyche that historian Ash (1980) has talked of the “strange death of Scottish history” and of the Scots being a people without history (Wolf 2010). In terms of culture, inferiorism as articulated by Fanon was deployed by Beveridge and Turnbull (1989) to express the historical neglect of Scottish culture which led Scots to absorb a sense of natural or spontaneous subordination within the national character.

Through the neglect of Scottish history as previously documented not only corresponds with Fanon’s concept of inferiorism but exemplifies Bourdieu’s notion of symbolic violence. By some Scots disregarding their own nation’s history it reinforces the idea of Scots yielding to England by seeing their own history as over and so they never give a thought to making it in their own right again as an independent nation and so they fail to challenge their own alienation. Perhaps the key areas where cultural inferiority has been established among the Scots is language. Well into the 1700’s Scots remained the established national language and the medium of high and low culture that was distinct from English. During this period Scots was the language of administration, legal documents, parliamentary records and the royal court with all social classes embracing it without any hint of inferiority (Hoffman 1996).

As England had a Protestant Reformation first in the 1520’s, the 1559 Reformation in Scotland was Scotland falling into cultural line with England and already in the sixteenth century however during the Protestant Reformation, Catholic apologists such as Winzet and Kennedy criticised the Protestant Reformers for importing German theological errors via England and doing so in the medium of the Southern tongue i.e. English. During the seventeenth century Scots’ linguistic value began to recede amongst the middle classes who perceived it as tainted and as the language of the less educated working class (Hoffman 1996). In 1561, the Bible was translated into English but, crucially, not in Scots so that Scots lost its prestige, while the Union of Crowns in 1603 saw King James VI of Scotland becoming James I King of England with the court being relocated to London where all royal affairs were now in English (Hoffman 1996). Crucially, King James’s relocation to London saw the Scottish upper classes follow with the intention of imitating their English peers leaving Scots socially adrift (Hoffman 1996).

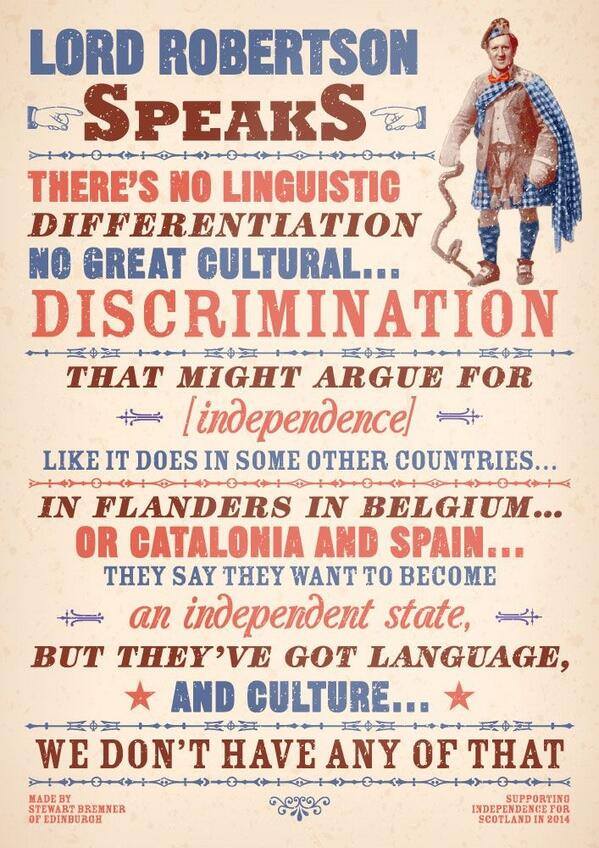

Through the Scotland Education Act (1872) the English language was promoted with the desire of suppressing Scots as well as Gaelic (Hoffman 1996). Education Scotland (2016) reveals the mistreatment of Scots in education was still evident until the 1980’s as children who spoke Scots could suffer corporal punishment for not speaking English at school. When viewed through the sociological lens of Bourdieu (1979), such realities evidence how language is crucial for securing cultural subordination and how the notion of ‘linguistic communism’ (where every social actor possesses the right and ability to speak and be heard) is not true in Scotland. The Scots language corresponds Bourdieu’s concerns as everyone does not have the right to communicate via Scots, as this can place them in opposition to the deemed universal language of English. If we take the term field (Bourdieu 1979) used to describe arenas where social agents operate within and include politics, parliament, patronage, court, and religion which grants legitimacy to the language which Scotland has lost, one player was Sir John Clerk of Penicuik (one of the Scottish negotiators of the Union of 1707) who remarked ‘’the English language … since the Union wou’d always be necessary for a Scotsman in whatever station of life he might be in, but especially in any public character’’ (cited in Balilyn and Morgan 2012, p. 85). This prophetic comment is epitomised in an incident at an Edinburgh court where a young man was held for contempt of court for answering aye (Scots for yes) instead of using the English form of yes (Crowther and Tett 1999). Similarly, Lord George Robertson remarked “Scotland has no language and culture” (NewsNet Scotland 2014) during the 2014 Referendum; a comment which is a wonderful example of cultural inferiority insofar as it suggests Scotland is void of a recognised culture by its own political elite and representatives.

Through the Scotland Education Act (1872) the English language was promoted with the desire of suppressing Scots as well as Gaelic (Hoffman 1996). Education Scotland (2016) reveals the mistreatment of Scots in education was still evident until the 1980’s as children who spoke Scots could suffer corporal punishment for not speaking English at school. When viewed through the sociological lens of Bourdieu (1979), such realities evidence how language is crucial for securing cultural subordination and how the notion of ‘linguistic communism’ (where every social actor possesses the right and ability to speak and be heard) is not true in Scotland. The Scots language corresponds Bourdieu’s concerns as everyone does not have the right to communicate via Scots, as this can place them in opposition to the deemed universal language of English. If we take the term field (Bourdieu 1979) used to describe arenas where social agents operate within and include politics, parliament, patronage, court, and religion which grants legitimacy to the language which Scotland has lost, one player was Sir John Clerk of Penicuik (one of the Scottish negotiators of the Union of 1707) who remarked ‘’the English language … since the Union wou’d always be necessary for a Scotsman in whatever station of life he might be in, but especially in any public character’’ (cited in Balilyn and Morgan 2012, p. 85). This prophetic comment is epitomised in an incident at an Edinburgh court where a young man was held for contempt of court for answering aye (Scots for yes) instead of using the English form of yes (Crowther and Tett 1999). Similarly, Lord George Robertson remarked “Scotland has no language and culture” (NewsNet Scotland 2014) during the 2014 Referendum; a comment which is a wonderful example of cultural inferiority insofar as it suggests Scotland is void of a recognised culture by its own political elite and representatives.

Billy Kay enquired to a Fife headmaster if pupils were encouraged to engage with Scottish Literature and was startled by his response: ‘’No. This is not a very Scottish area” (Robinson 2008, p.5). Other examples of what seems to be cultural ‘self-hatred’ came when, in response to the Scottish Independence Referendum in 2014, Conservative councilor Callum Campbell and Labour Councilor Danny Gibson proposed to have the Scottish Saltire removed from Stirling council’s headquarters and to replace it with the Union Jack (Wings over Scotland 2013). Both councilors said they wanted to see the emblem of ‘our country’ flying from Stirling council’s rooftop, evidencing perhaps the native abandoning their own national identity and culture and embracing that of the coloniser. These councilor’s allude to Fanon’s theoretical perspective of inferiorism but also to Bourdieu’s idea of symbolic violence whereby Scots not only participate in their own servitude but are the creators of it.

The loss of the yes campaign in the Scottish Independence Referendum (2014) can be identified as a contemporary example of the Scottish cringe. The people of Scotland shunned their opportunity to reclaim their liberty the reasons for which are captured in sociological theorist Paulo Freire’s quote ‘’The oppressed, having internalized the image of the oppressor and adopted his guidelines, are fearful of freedom’’ (Freire 2016, p.46).

Thank you for an interesting article. Some great points and interesting nuggets.

Two points I’d like to add though:

1) I think it’s important to defiance what is meant by “English ” and “English culture”. I don’t think we are are talking about the majority English of the English population (peasantry) who were dispossessed from their land, and even there bodies, when Henry the Eighth decleard himself sovereign and owner of England and its people – his subjects (and were then thrown into the hellish factories and wars of the elites). As far as I understand it, this total dispossession never happened to us Scots (clearances, factories, wars yes, but we still have our sovereignty and this is not insignificant!). So, though we appear weak, we are actually in a much stronger position than our brothers and sisters in England. Hence London’s current consternation and historical suppression of history and facts!;

2) you conclude that the 2014 independence referendum is a modern example of Scottish self inferiority. But, the data clearly shows that if you take our none Scots and the older generations that really did have a post-WWII British “experience”, actually, in the face of hundreds of years of psychological bullying and a wall of corporate propaganda, we actually did vote to end the union. Scotland was brave :). Let’s celebrate this!

I think its really important to be very clear to define the terms we use, build bridges with people all over these islands and be specific about what we are dealing with – money and corrupt power largly based in The City of London 🙁

Thanks Michael, really good points. Your first point about dispossession and enclosure has been picked up recently by Alastair McIntosh with some research looking at why the land reform movement is so behind south of the border.

Thanks Mike. I should learn not to comment late at night! So many “typos”. That’s great that Alastair is looking at this.

Excellent article and ever so true. Makes me very sad. Education is the only way out. (starting with the tutors).

I have usually found that the more “educated” a person is, the more invested in elite propaganda they seem to be 🙂 Is it because education that threatens the power structure within which it is being delivered, is obviously not going to be tolerated?

So, in theory “education” sounds good, but in practice, are there any examples of “education” leading to liberation? Perhaps by following the teachings, and much more importantly, the experience based practices of the Buddha – who said himself: don’t belive me, verify everything for yourself.

I think we need to be less focused on education (ie, getting tied in conceptual knots) and more focused on embodied community and cultural practices like dancing and signing etc. These things that have been at the heart of our communities for thousands of years, that develop trust and bring us into connection with ourselves, others, and a much deeper and more meaningful wisdom of how to live and organise ourselves 🙂

It’s and idea!

Very, very good article.

Although the author did give me a laugh when quoting Carol Craig’s writing in support of the theory of the Scottish Cringe. She, of course, exemplified that cringe when she campaigned for the union in the independence referendum

Enjoyed this. I have a special perspective, as I came north from England to Scotland in 1979, to a nation full of cultural cringe, and have noted it and spoken against its inferiority complex and lack of national confidence ever since. As one of the Scottish diaspora returning to Scotland, after an English raising, I had an acute awareness of the issue. To be a Scottie in Southern England was to one of a disparaged minority. Englishman, Scotsman and Irishman jokes were rife, and while the Irishman got the butt, the Scotsman was portrayed as mean, reactionary, and dim. I was proud of my Scottish heritage in lots of ways, my grandfather who had come south on one side of my family had a Glasgow medical education, was son of the Manse, and had colossal drive, seen on golf course (honed in shinty playing) and in business. My great grandfather on another side of the family, part of Dundee establishment, had an architectural qualification and with others built up the Northern Power House of Greater Manchester, which in those days lived up to its name. It was clear to me, as to modern British historians, that English Empire under the Union Jack had been built, administrated, and served by vigorous and accomplished Scots more than any other. It was also clear, subliminally, that if England had allowed Scotland to be, instead of bleeding it dry, this energy would have prospered Scotland into a bloom of nationhood. While all the points in the article hold good, psychologically, there is the result of a military repression and a legal persecution – Scots were forbidden their Gaelic (not mentioned), their tartan and their cultural life of pipes, bands and folk songs, and shoehorned into Englishness: the tragic social history required massive emigration too. I suppose in fact this article deals with the Central Belt and Lowlands only – and the Fife anecdote is revealing – while Fife ought to be its own “Kingdom” as it proclaims, in fact it studies hard to make its sons and daughters ready for the very English life of Edinburgh Town. Anyhow, apart from the wool gathering of asides, things have changed. Sturgeon is right to say that Holyrood has given Scots their focus for self determination back, and Dewar was right to negotiate through a very tilted playing field to secure and establish Holyrood. Having rebalanced our psyche, let us now reclaim our history. We don’t need all these reasons for doing it: it is axiomatic that a people, a nation with sovereign right, needs to know its history, and, of course, that requires some recovery of the truth, and a rewriting of the falsehoods, by the new Winners, who are the Scots returned home to their senses!

“[…] while Fife ought to be its own “Kingdom” as it proclaims, in fact it studies hard to make its sons and daughters ready for the very English life of Edinburgh Town.” Hei, haud on pal, some of our bairns escape to Dundee or Glasgow!

Aye, Tom, right enough. But also Alistair’s ‘very English life of Edinburgh Town’ is a bit of a sweeping statement, as it depends which bits of Auld Reekie you’re talking about. Having said that, I agree with much of what Alistair says about a step-by-step reclamation of our history and culture. We’re in a better place than we were, and that makes it easier to move on to the next better place. Given the kind of background described by Colin Turnbull in his article, 2014 was an astonishingly good result, and, as has often been remarked since, ‘the genie’s oot the bottle and it’s no gaun back’. As with devolution, we probably always needed two shots at independence which is why the other lot are so visibly panicking now, as they can see the second one being lined up.

i can remember in the early seventies, boys in my primary school class being beaten for saying scots words like “aye”. It actually happened. I went to Robert Gordon’s College in Aberdeen, the same school as Michael Gove. Maybe that is what happened to him.

I too remember my Fife primary school years in the early ’70s… and the exact opposite experience to those recalled here, rather, industry shaped school life – oh, and an annual Burns recital with no exceptions and months of lead-in. Whereas in South Yorkshire only a few years later, it was the case that kids were chastised for their demotic, regardless of how much ‘Kes’ was thrust at us otherwise.

So perhaps, instead, there’s actually a class issue at play in the invention and political utility of so-called ‘cringe’, and not just by ‘wellbeing’ neoliberals and their liggers. Class, after all, and not nation-ed identity, is Bordieu’s focus. But then the author’s methodological nationalism (the organisational logic of nationed statism) collapses the possibility of any such analysis. A logocentrism that desires in this case a nation-ed centre as original guarantee of all meanings …no thanks 🙁

You are presenting a false dichotomy here. I agree with you that in cases such as getting physical punishment for using words like “aye” or other demotic language in various parts of the UK did, indeed, have a very strong class element to it. However, this does not negate the author’s thesis that there is a suppression of a national language or culture at play, too.

One of the contributors above makes the point that there are parts of England where the local culture and way of speaking was suppressed to impose a British language and culture. Scotland, because it is a historic nation, retained institutions which were able to sustain a sense of Scottishness, even during very ‘dark’ periods since the 1707 union.

On a personal note – my mother was a native Gaelic speaker (she spoke and wrote English excellently, idiomatically and with precision), but at school during the First World War, she and her classmates were corporally punished for speaking in Gaelic on the way to school and in the playground. The language was disparaged by the teachers. 60 years later, when she was dying, she was in tears at the memory of the injustice and cruelty of this. And, yet, there was an element of apology in her emotion – the victim blaming herself for her own ‘fate’. This is how insidiously the ‘Scottish cringe’ infected the psyche of many of us.

Congratulations to Mr Turnbull,with particular thanks to him for quoting a hero of mine, Paulo Freire.

Thoroughly enjoyed the article and all the comments.

I bear witness to meeting an old man in the public hall cafe in Lochmaddy while my wife and I were on our grand tour from Barra to the Butt by motorbike about ten years ago.

We brought up the subject of language and he told us, with tears in his eyes, about being physically punished for speaking Gaelic in school. I assume he was told not to speak it at home as he confessed to not ‘having’ it, hence his tears as he confessed his shame at the situation.

Good stuff.

I recall attending the final day of a conference on foreign and defence policy organised the University of Glasgow in the run up to Indy Ref 1.

Speaking at the event were many Glasgow University alumni that were, or had recently been “something” in the UK’s defence and security establishment or related academia.

Having listened to all of the earlier panels of the day carefully, during the Q and A, of a plenary , half joking , I posited the notion that that a key feature of the geopolitics of an Independent Scotland was the Scotland had no distinctive geopolitical characteristics.

The audience, made up in the main of under and post graduate students of foreign and security studies responded to my quip in gales of laughter. The panel and many of the other very prominent speakers were somewhat stony faced and if looks could kill.

Though, in fairness, a feature of the general discourse around the foreign and defence policy debate during Indy Ref 1 was of a pretty low standard all round.

I recall a particularly ridiculous contribution , at another seminar , held in the Scottish parliament , during the same period , this time hosted by the Royal United Services Institute, the UK’s most prominent and , it is claimed , the world’s oldest military think tank.

One of the panellists , posited that ridiculous concept of the Scottish soldier as being imbued by some sort of exceptional martial spirit. I have always regretted not throwing back to the visitor from Whitehall that he was in effect proposing a 21st century Scottish version a Charles Mangin’s La Force Noire.

there has been one major sea-change in the “cringe”…I would suggest that it no longer applies to females. today`s girls are assertive and confident, back in the 1950s/60s their grannies (as teenagers) still were encouraged to regard themselves as second class citizens.