The Mental Health of Palestine

Brendan Duggan is the joint runner-up winner of the 2020 Ian Bell New Writing Prize sponsored by the NUJ in association with Bella Caledonia. The awards will be presented by Mandy Bell and the judges at the Aye Write literary festival, on Saturday 14 March at the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, following a talk at 6.15pm by Tom Roberts, author of The Making of Murdoch: Power, Politics and the Man Who Owns the Media.

For Dr Hakim, it’s almost a three-hour drive from Haifa, where he lives as a Palestinian citizen of Israel, to the West Bank where he is the director of a small clinic that provides therapy to local Palestinians. He travels in the unbearable Arab heat and on the way there he is stopped at checkpoints, searched and questioned by Israeli soldiers. Doctor Cesar Hakim himself has strong features, almost lion-like with tanned Palestinian skin and is compelling and firm when talking about his work. In between his sentences, he is quiet and earnest.

He arrives in Bethlehem, a historical place for Christians, Muslim and Jews. In his office, his client waits, a woman in her late 40s. Culturally this is frowned upon; a woman alone in a room with a man who is not her husband.

This woman, who will remain anonymous, is suffering from depression and anxiety: when she was young she was forced into an arranged marriage. “She loved someone else, not her husband, but her parents and brothers didn’t accept him,” Dr Hakim told me. “She acted like she denied her real feelings because she has to be a typical woman in the culture that woman have certain ways of behaving.”

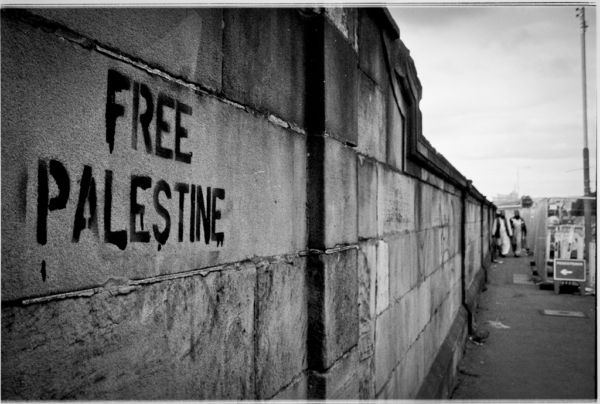

She had become trapped inside the walls of her own life, whilst out of the window she can see the large wall that separates Israel from the West Bank and restricts movement for Palestinians. Dr Hakim tells me this story, maybe because he wants this particular to take me into the wider, more complex issue. “She lives very near the wall, very near the checkpoint. The checkpoint, the wall.

“Symbolically it is in the context she lives. Palestinian people are denied how they live, they are restricted from movements. Palestinians are stripped of their subjectivity, they have to go under certain rules.”

The conflict between Israel and Palestine is one of the most important news stories in the world. The over 100 year conflict in which the two groups claim the same land has led to attacks from both sides. What was once under Ottoman control, was diverse in mostly Muslims and Christians with a small Jewish population. Then after World War I and the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the British took full control of what they called the British mandate for Palestine and a Palestinian identity began to develop.

At the same time, the rise in Zionism, a case for a Jewish state, led to an increase in Jewish immigration from across the world. This only increased after the Holocaust, when many Jews fled to escape the horrors in Europe.

In 1947, the UN decided to divide the area into Palestine and Israel, giving both people their own nation. Whilst Jews accepted the deal the surrounding Arab states saw this as nothing more than European colonialism. They declared war on the new state of Israel, a war which Israel would win. This led to what the Palestinian people call the Nakba, where an estimated 700,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from their homes in a now Israeli-occupied Palestine.

In 1967 another war broke out, this time lasting only six days and by the end, Israel took control of all of Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip: each was home to thousands of Palestinians. That is where we currently stand and the division between Israeli and Palestinian people continues. The question Dr Hakim faces every day is what displacement, occupation and conflict does to the mind.

In Haifa, there is infrastructure, good practice, systems and communication. Dr Hakim regularly visits schools to help children and has a strong relationship with the establishments in Haifa. In Bethlehem where his clinic is located, the structure is lacking and the culture is more difficult to manoeuvre through.

On the street nearby, you can smell the different cultures – chicken, falafel and you can hear the bells of a church. But behind it all, there is a lack of structure, especially for psychology. In his clinic, the small team

of psychologists treat mostly children within local schools, villages and small communities across the West Bank; and they find it more and more difficult to treat as many people as they can. In one instance, when dealing with a child, the cause of whose trauma crossed over into the illegal, the family asked Dr Hakim to please, “keep it in the family.”

Whilst the news covers the politics of the area, mental health issues in areas like the West Bank and Gaza go unreported. These issues are often sidelined by the arguments over who is in the right and who is in the wrong.

One of the biggest issues facing Palestinians is complex trauma, a form of trauma which, like the name suggests, is more elaborate and severe. “A complex trauma means that you live in everyday events that might be traumatic.” Dr Hakim explains to me from his home Haifa. “All the people who live (in Palestine) are under an occupation, which means you have a restriction of movement and you have to live under certain rules otherwise you will be detained.”

Complex trauma is caused by a build up of traumatic events that occur on a prolonged or daily basis. Complex trauma or complex PTSD was popularised by the psychologist and author Judith Herman in her book Trauma and Recovery where she wrote that those experiencing long-term trauma show very different and more severe symptoms than those who experience ‘single-event trauma’.

It is more commonly found in those who are in abusive relationships. Dr Hakim explains that “If there is a woman that comes to treatment and she is beaten by her husband, first of all, you have to make sure this woman is secure before you start therapy. We have to stop the traumatic events that she lives in. You can’t do this with for example children in Palestine. “This isn’t possible for most Palestinians because of the occupation and the restriction of movement, for example, the Israeli West Bank Barrier.

This feeling of being trapped and having your personality altered because of your previous trauma is shared by all those who struggle with trauma. Judith Herman wrote about a girl who had been abused as a child and how that continues, clinging to her into adulthood. “Many abused children cling to the hope that growing up will bring escape and freedom,” she writes, “But the personality formed in the environment of coercive control is not well adapted to adult life.

“The survivor is left with fundamental problems in basic trust, autonomy, and initiative. She approaches the task of early adulthood – establishing independence and intimacy – burdened by major impairments in self-care, in cognition and in memory, in identity, and in the capacity to form stable relationships.

She is still a prisoner of her childhood; attempting to create a new life, she reencounters the trauma.”

In Gaza, years of conflict and poor quality of life has led to high amounts of complex trauma throughout the region. With clashes on the border between Palestinian protesters and the Israeli army, many Palestinians have been killed or been severely injured. The World Health Organisation has reported that “in 2018, 299 Palestinians were killed and 29 878 injured in the context of occupation and conflict”, the majority of which were in the Gaza strip. This is even more relevant for children, as of 2019 “54% of Palestinian boys and 47% of Palestinian girls aged six to 12 years reportedly have emotional and/or behavioural disorders.”

What does mental health have to do with politics in the Middle East? Surely once we have solved the conflict then we can focus on the mental health crisis, or is this a backwards approach? When a whole community is suffering from complex trauma, it can cause them to act and think irrationally, often violently.

Humans have this remarkable ability to adapt to their environment, even if that environment is dangerous and unhealthy. Those who remain in a traumatic environment where they feel like objects can slowly become dangerous to themselves and those around them, a state of mind which is passed down from generation to generation. Dr Hakim argues that Ignoring the mental health crisis will only escalate the conflict and lead to more divide and more violence. A traumatised population is a huge barrier in the way of rebuilding that stability and finding any other solution to the crisis.

I think of the many times I’ve sat at home, and on the news footage of cities in disrepair from places like Iran and Syria were on our TV while we ate dinner. “Tell me if that revolution was worth it now” I would hear someone say. Nobody entertains the idea that their struggles go beyond war and in a way is far more dangerous, as it lives among them like a toxic member of the family.

What Dr Hakim and his team are trying to do is help the Palestinian people deal with and process their traumas in the hope it will help them find better and more non-violent ways of resistance. Complex trauma isn’t easy to understand but once you do, you can see how it affects countries caught in conflict and how tackling mental health issues could be a way to resolve it.

As a psychotherapist I wholeheartedly endorse this article. Thanks to BC for giving a platform to so important an issue.

I’m ashamed to say I couldn’t finish reading this article although I will keep coming back to it until I do.

To speak of the appalling injustice inflicted on Palestine, these days, is practically illegal! How can we have let this happen?

I wonder how many of the those people who fondly regard the British Empire (in a recent poll) are familiar with the great Palestinian Revolt of 1936–39 as described in a chapter of John Newsinger’s The Blood Never Dried: A People’s History of the British Empire? Newsinger describes the lead up to the revolt, with British interest in Palestine primarily strategic. Then the British terror and ‘Gestapo tactics’ that followed. Apparently the RAF conducted many ‘Guernicas’ against Palestinian villages, yet the conflict got far less attention than the concurrent Spanish Civil War. And the British occupation was seemingly supported by Labour Party hierarchy as well as Conservatives.

There is a Wikipedia article, though I have only skimmed it:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1936%E2%80%931939_Arab_revolt_in_Palestine

Events like those can only cast a long, dark shadow, I guess. While Palestinians may have been able to take some comfort from support throughout the UN General Assembly, it seems that the five permanent members of the Security Council are never going to bring about a just resolution. And without that hope, I am not surprised that the mental health of Palestinians continues to suffer.

Incidentally, I watched a BBC Storyville documentary called Advocate: A Lawyer without Borders, on “Jewish lawyer Lea Tsemel [who] is a controversial figure in Israel. For the last 50 years, she has fearlessly defended Palestinians prosecuted in Israeli courts for resisting the occupation.”

There is a question put during the documentary, is it better to still believe in justice or not? In other words, is a belief in justice good for your mental health in a fundamentally unjust state? I am not sure if that is easy to answer.