The Fifth Man

John Cairncross, the alleged Fifth Man among the wartime Cambridge spies in popular mythology, has been painted as a Communist sympathiser and cadre motivated by his experience of the General Strike and Great Depression in the Clyde Valley of the late 1920s and early 30s. He was nothing of the kind.

John Cairncross, the alleged Fifth Man among the wartime Cambridge spies in popular mythology, has been painted as a Communist sympathiser and cadre motivated by his experience of the General Strike and Great Depression in the Clyde Valley of the late 1920s and early 30s. He was nothing of the kind.

It’s one of the merits of Geoff Andrews’s well-researched, diligent new biography* that it debunks this and other myths. Cairncross was, he shows, much more motivated by a visceral disagreement with the pro-appeasement ideology and attitudes of swaths of the British ruling class he encountered and by an intellectual, moral and cultural affinity with the anti-fascists he met and grew to admire.

In this and other respects, his life-story has contemporary resonances, with the resurgence of the far right and what the French call fascisant mentality along with nativist protectionism in response to both pandemic and economic collapse. From his school days, Cairncross was a firm believer in (Scottish) Enlightenment values; he remained an exemplar of Davie’s Democratic Intellect.

Born in Lesmahagow in 1913, the youngest of eight siblings in a sturdily lower middle-class family of an ironmonger and a schoolteacher, both wedded to concepts of self-improvement through education, Cairncross excelled at school, including at Hamilton Academy. At 17 he headed off to Glasgow University to join his nearest brother, Alec, later to become an economics professor/Labour government adviser.

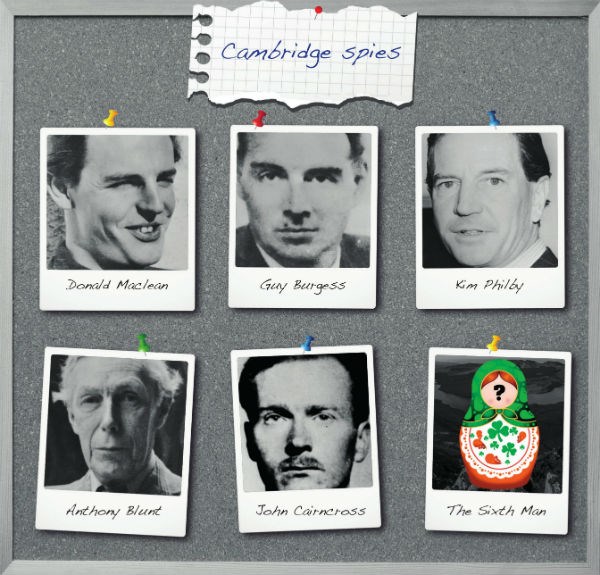

A student of French and German, Cairncross, Andrews argues after trawling his private diary, began his anti-fascist odyssey during a cycling/walking tour in Germany and Austria in the summer of 1932 where he enjoyed long discussions with both Marxists and proto-Nazis. After a sojourn at the Sorbonne, he continued his studies at Trinity, Cambridge where he coincided with art historian (and Fourth Man) Anthony Blunt, before coming top in the entrance exams to both the Home and Overseas civil services. Befriended (from an arrogant distance) by Guy Burgess and, critically, by James Klugmann (a Third International operative eventually), Cairncross was recruited as a Soviet spy in a memorably stumbling encounter behind a bush in Regent’s Park by Arnold “Otto” Deutsch in 1937.

Here Andrews fails to clear up what he admits is the main problem in dealing with Cairncross and his legacy: the Scot’s failure to set out in adequate detail the regularity of his dealings with his Soviet controllers, how much he was paid, and why, ultimately, if “neither an uncompromising Stalinist nor victim of the ‘God that failed’,” he gave secrets to Moscow with such largesse.

Here Andrews fails to clear up what he admits is the main problem in dealing with Cairncross and his legacy: the Scot’s failure to set out in adequate detail the regularity of his dealings with his Soviet controllers, how much he was paid, and why, ultimately, if “neither an uncompromising Stalinist nor victim of the ‘God that failed’,” he gave secrets to Moscow with such largesse.

Nor does he fully explain why and how Cairncross fell out with his UK Government employers who found his work slovenly at times yet sponsored his membership of the Travellers’ (spooks) Club on Pall Mall or, indeed, approved his transfer to Bletchley (from where he took, stuffed in his briefcase and/or trousers, copious scripts of unredacted Enigma data to hand over to the Russians and thereby inter alia help the Red Army win the decisive Battle of the Kursk against Hitler’s 8th Amy in 1943). Nor why he carried on spying post-1945 (“for reasons of self-preservation” doesn’t cut it).

Elsewhere, in a review of a lesser, utterly pro-Establishment recent biography, Trevor Royle has dubbed Cairncross the “Mr Bean of the spy world” and “far too thrawn and unclubbable” to fit in. Whereas, Andrews opines, he was far more an intellectually self-confident albeit prickly Scot out of sorts (and tune) with the prevailing (still) Old Etonian/Oxbridge cultural/ideological blindness of the Brits in power.

Eventually, after a series of adventures and mishaps meticulously documented by Andrews, Cairncross the scholar ended up in Italy, then France, where he was “unmasked” as Soviet spook by Chris Andrews, now MI5’s official historian, and had a stroke, before finally landing in a Herefordshire village where he died in 1995. As well as a trio of books in French on his beloved Molière (and other tomes) he left behind an incomplete autobiography and translations of Corneille and Racine plays still in use today.

His niece, Frances (of the eponymous report into the future of ‘high-quality’ journalism), suggests in an interview with Andrews her uncle would probably have voted for/supported the SNP today. Again, there is no evidence for this. Indeed, his widow (now my second wife), insists he never discussed Scotland at all, remaining a citizen of Europe and/or the world until his dying day. He is much more likely a Liberal. Whatever the truth of the matter, Andrews has produced a sympathetic, not uncritical and sometimes puzzled account of a very Scottish spy.

* Agent Molière, IB Tauris, 320 pp, £11.88 e-book

Name of author?

Yes. Who wrote this review?

Very interesting, but would like to know who is the author.

My mother was a student of Alex Cairncross, at Glasgow University, and then after she graduated worked in London during the war, in the ministry of aircraft production.

A review of a book about one of Britain’s most (in)famous spies John Cairncross (1913-1995), by a reviewer who is married to Cairncross’s widow (whom I understood was Gayle Brinkerhoff, who has been interviewed in the press about Cairncross); a reviewer who remains anonymous. The review itself is an exotic mystery.

Cairncross has never been so well researched as the other leading Soviet spies (Burgess, MacLean, Philby and Blount); but while research of this kind is of course legimate and important, what is perhaps much more telling is the contrast with the notable lack of equal historical research interest in British Right-wing intelligence failures; particularly before and during WWII; the Venlo incident, 1939; or Lord Sempill (see ‘Churchill protected Scottish peer suspected of spying for Japan’, The Independent, 24th August, 1998), or sinister figures like the MI5 officer, and first Director of Research for the Conservative Party, Sir Joseph Ball. As far as I know there is no biography of Ball.

The reviewer is David Gow. Its not anonymous.

There was no name supplied, I had no idea of the reason and it seems to me in that context ‘anonymous’ is simply descriptive, not pejorative.

Hi John, some glitch I’m afraid, its displaying now.

I’m a former Guardian journalist who edits sceptical.scot and is on editorial board of socialeurope.eu

David Gow. Thanks. I didn’t see author’s name at the piece itself.

After The War (WW2) to be a communist was an honourable state and had been since the 1930s. Russia had been an ally against Nazi power and it was, of course, a Communist country. To be ‘Red’ and working in Clyde Shipbuilding was a high status for a Glasgow man.