Where are the Women? Imagining a Different Landscape

‘He who controls the past, controls the future. He who controls the present, controls the past.’ George Orwell, 1984

He.

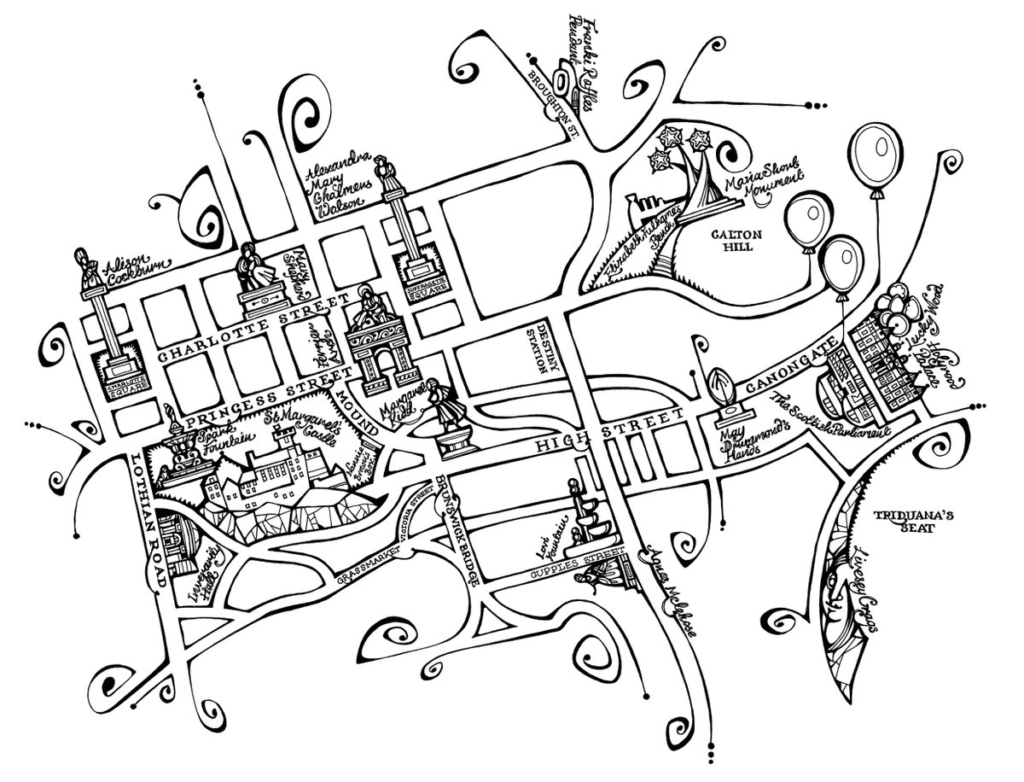

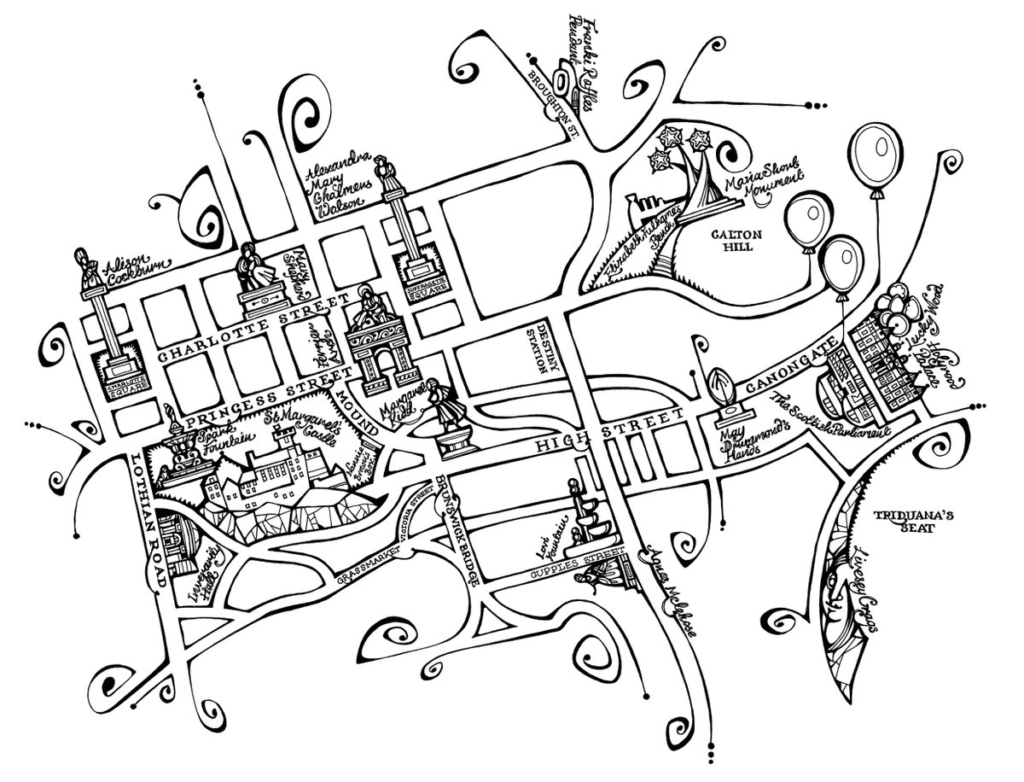

In 2018 I was commissioned by Historic Environment Scotland to remap our country as if the landscape had been dedicated to the memory of women, rather than men. A committed feminist and equality campaigner since my teens, the experience radicalised me. I have been writing books about female history of one kind or another for over 20 years but I had not realised the scale to which our built environment and landscape excludes the achievements of women. When I started, although I knew a lot about the two periods in which I normally write (the late Georgian/early Victorian and the mid-20th century) I had little idea of the breadth of female history in other eras – though I knew the main players.

Within weeks of starting the project (which blossomed into a book with a projected word count that almost doubled during the writing because there were so many stories that deserved to be told) I became furious. In remapping the landscape I had studied our existing one and realised how patriarchal it was. And not only that – it was hetero-normative. It was white. It was Christian. As well as so, so male. While some women were memorialised (mostly white, straight, Christian women) female memorialisation did not include even most of the ‘high rollers’ – women who genuinely had a huge impact on this country. Overall, the number of female memorials lagged embarrassingly behind male memorialisation. The Women of Scotland Mapping Memorials project is valuable but also saddened me.

Why are these memorials all we have? Women, for the most part, are remembered only on a gravestone or with a plaque. Where a female monument was instituted I noticed that there was a sense ‘let’s draw a line under this issue.’ The Mary Barbour statue in Glasgow prompted a flood of ‘you’ll have had your female memorialisation,’ and the lack of diversity in suggestions of female achievers when an opportunity arises, remains disheartening. The same names come up again and again – Muriel Spark, Mary Barbour and Elsie Inglis being notable by their reoccurrence. Ask about men and you get a lot more choice – male history is simply known in more detail.

Our sense of self and of where we come from is not confined to history books. As the feminist writer and the inspiration for my project, Rebecca Solnit, put it, “I can’t imagine how I might have conceived of myself and my possibilities if, in my formative years, I had moved through a city where most things were named after women” In other words, if women (or for that matter any other minority group) don’t see themselves represented in the world, the unspoken message is that our stories – and indeed achievements – don’t matter. This raises an interesting question. All the white men around me live in just that world – a place where their images are raised on plinths and streets are named in their honour. In writing Where Are The Women, what made me most angry was understanding the entitlement I might feel if my gender was included and the impact that would have on my confidence, particularly as a younger woman – the sense of what I might achieve – and of that achievement being normal. It was a window into the world of our culturally dominant gender and one that I believe is hugely important for all of us, but particularly for younger women of all races, sexualities and beliefs.

The #BlackLivesMatter movement has highlighted the inappropriate nature of some statues and street names in our cities that commemorate slavers – the Edinburgh preoccupation with men from the Dundas/Melville family being a high-profile Scottish example. I have long been of the view that statues, street names and named landscape features need to be audited – do we really want to dedicate high profile public space to statues of, for example, unsuccessful missionary David Livingstone with whom late Victorian Scotland had a kind of obsession, when we might instead use the same space to memorialise the woman for whom the term ‘scientist’ was coined, Mary Somerville or Quaker, Eliza Whigam – one of only six women who formed the Trans-Atlantic Anti-Slavery Sisterhood.

While the built environment and landscape are not by any means the only battleground to advance equality, we are stuck in a visible vicious circle by them – if women’s achievements are constantly downplayed and men’s are publicly more valued, equality will remain an uphill struggle. For all members of society to contribute, it is important to show all contributions are valued, be they from mainstream, majority communities or from minorities. While women make up over 50 per cent of the population, they are still a marginalised group. If proof were needed of how controversial this subject remains, the outcry in 2017 in the run up to Jane Austen’s appearance on the Bank of England ten pound note is an excellent example. Pro-Austen campaigners were vilified and repeated attempts made to dismiss Austen’s work as ‘too domestic’. The comments made remind me of many responses last week by fascist demonstrators and hard-right commentators about taking down Colston’s statue in Bristol – we like what we have. What we have is the only truth.

In the end I fitted 1200 women into the Scottish landscape to create an imagined guidebook to our country – a female one. I learned that our foremothers are quite as remarkable as our forefathers and just as important. There is a vogue for talking about ‘invisible’ women but these women were not invisible within their communities, only in public memory. It is (as Austen might have put it) a fact universally unacknowledged that a woman once she has died will have her memory subsumed into the achievements of the men around her. When writing the book I ground my teeth at the memorial to political activist Lady Margaret Crawford at Dunfermline Abbey whose monument simply reads ‘Mother of William Wallace’ without even recording her name. I raged when on the anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement broadcasters neglected to mention the contribution of Mo Mowlem until one of her relations phoned in to point out the lapse.

We desperately need political and social reform at almost every level of society on almost every issue. We have needed change for a long time –Brexit and the Covid crisis have highlighted how badly our systems are broken and/or out of date. But change is achievable and more so if we change how we memorialise achievement. In a speedy response to events, the Policy and Sustainability Committee of City of Edinburgh Council met on 11th June and decided that within the coming 3 months they will review features such as street names and statues that bear the names of people connected to the slave trade.

This is a start.

The changing of street names in particular is a consultative business involving all residents on the streets concerned – the council in normal circumstances consider doing it only as a last resort but the crisis point we’re at may mean CEC take action. If they do I hope they use it as an opportunity to remove rather than just explain several statues and street names in the city – perhaps using Berlin as an exemplary model of the way that we can own our more difficult history and not glorify it. These changes will have the benefit of also making room for more worthy recipients of public celebration – people who deserve street names and statues. Colston, Melville and their ilk should be in museums, but let’s raise different monuments on our newly named streets and in the wider landscape to the people who advanced the things we love about our culture and please let at least half of them be women.

Image credit: Edinburgh map drawn by Jenny Proudfoot

My first thought was we need a monument to Hypatia, killed by a group of Fanatical Christians for being clever.

You make some good points. I did not know about Dundas before this started and see him as an ambiguous figure: against the slave trade, according to wikipedia but not wanting it cut off abruptly.

Most of the people on today’s controversial statues have done good things as well as bad and we are not judging them by the standards of their own time, which were not rigid anyway. We need to acknowledge the good they did not just the bad.

Personally I could do without the statues of long dead people anyway, good or bad but they provide good starting points for research

It’s interesting that the author mentions Muriel Spark. The nearest that author has to a memorial is the re-named Vennel in the Grassmarket, and it memorialises Jean Brodie – I guess because Spark’s most famous creation is more widely known than the author herself. Might as well have called it “Maggie Smith Steps”.

Sarah

How could you tell the majority of statues were not women?

I am not sure that replacing the built environment support for The Great Man (Occasionally Woman) Theory of History with the Great Person Theory of History really helps much. Incidentally, I think the battle has already moved on to the natural environment, with prodominently male genetic tinkerers creating a Frankenstein’s brood (possibly out of fertility envy).

If people ‘deserve’ street names and statues presumably they ‘deserve’ honours and awards, yet look how corrupt those systems are. What happens when the paint flakes off a whitewashed reputation?

Thank you Sara for this very interesting piece.

I finished a MLitt Sociology in the early 1990s. When I began my first visit was to Aberdeen University Library . I had the support of a female librarian. She searched the libraryOnline for some time but could not find any Cultural Identity or Cultural History references for Women in Scotland.

Women in Scotland ,I discovered ,had been written out of history for two hundred years following the Scottish …… They were documented as whores and sinners. John Knox and cohorts ensured women’s silence.

The academic research situation has improved thankfully but we do have this profound silence and silencing to overcome. Rebecca Solnit ‘s idea of the positive on women’s sense of self being part of respect and recognition of their cultural and other contributions was uplifting .

I would have loved to go on to Phd level but my life circumstances made this impossible. I was interested in looking at the situation of women in the Netherlands who have the best health statistics and women in Scotland who have the worst in the western industrialised world. What factors in both cultures allow this situation?

Apologies missed inserting Scottish Reformation

Hi Sara

Interesting project. I’m guessing you already know about the Women of Achievement trail?

https://www.ourtownstories.co.uk/story/582/