Operation Legacy

At the end of the week Dame Vera Lynn died triggering a new outpouring of World War Two nostalgia. Cliff Richard and Michael Ball were interviewed and news programmes flooded with tributes and remembrance. The Queen had previously echoed Dame Vera’s famous WW2 anthem during a speech aimed at people separated from families and friends during the coronavirus lockdown in April. She told the nation: “We will be with our friends again, we will be with our families again, we will meet again.” Prime Minister Boris Johnson said Dame Vera’s “charm and magical voice entranced and uplifted our country in some of our darkest hours”. Some claimed she had helped Britain win the war.

But who am I to mock people who went through a war together? I’m nobody and there’s nothing wrong with remembering someone – especially for older people who are isolated and frightened.

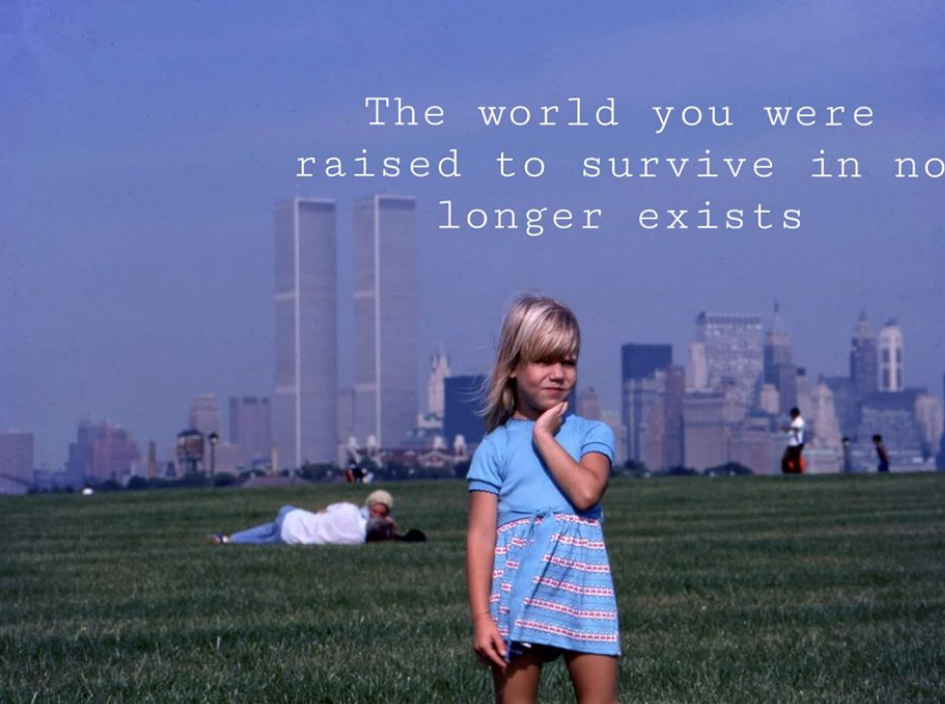

But the singers death did seem like another marker in a passing of time as Britain morphs and dissolves. For a country drenched in nostalgia, looking backwards and constantly referencing the war is a problem. For a society in lockdown looking backwards to the pre-covid world has become an obsession now heightened as ‘lifting the lockdown’ beckons. The vision for the future has been reduced to a trip to a gardening centre.

We’ve been locked into this worldview for a while. The thankfully now dead Keep Calm and Carry On meme dates from back in August 2011, when an entrepreneur registered the slogan, but it had been kicking about before that. England has been clinging to the Blitz spirit for at least a decade. Brexit groaned with bitterness and regret, harking back to a mythical lost Britain of the 1950s with a thinly coded sub-message of: Make Britain White Again. Now Brexit, Coronavirus and Black Lives Matter swirl together. Now the promises and expectations of “taking back control” and the sunny uplands of Brexit are looking shabbier than ever as “statue defenders” protect an imagined past with relentless violence and Downing Street is forced to defend Boris Johnson’s decision to spend nearly £1m of taxpayers’ money getting his RAF Voyager painted in red white and blue.

But if the symbolic is working hard to obliterate the harsh reality of British failure, it will have to work harder. On Thursday the campaign to bring down a statue of Cecil Rhodes at Oxford University marked a significant victory after Oriel College voted in favour of removing the controversial statue of Rhodes. The campaign group Rhodes Must Fall in Oxford called for the removal of a statue of the slave owner Christopher Codrington at All Souls College, and for increased representation of BAME students and staff. They said the project to “decolonise” the institution would not end with the removal of the memorial. Over at Twickenham the RFU has decided to cease the singing of Swing Low, Sweet Chariot by England supporters, admitting that many of them are unaware of its origins as a song about slavery. England fans have previously been criticised for “cross-cultural appropriation of a US slave song”, and the Black Lives Matter movement has brought renewed focus on its airing at Twickenham and matches abroad.

As the collision between myth and reality, modernity and imperial past continues, what is left is a void culture. Into this chasm steps the unfortunate Dominic Raab who this week responded to an interviewers question about “taking the knee”: “I take the knee for two people: the Queen and the missus when I asked her to marry me”. As a nation processed the political-psychological implications of this statement Raab threw in that he thought the action had something to do with Game of Thrones.

2020 reality seems to shift between feeling like an episode of The Simpsons and Terry Nation’s post-apocalyptic tv show The Survivors. As moods swing between tenacity and trauma we engage in the trivia of watching the drama unfold and tending to our domestic tedium. This notion of the past catching up with us seems irresistible, as if long decades of denial and manipulation of the past is now over-taking us. The notion of “erasing history” has become a desperate slogan for those denying this process and clinging to a reality constructed in stone and bronze adorning plinths erected by our white forefathers.

But if this history has been created it has also been destroyed.

Reporting on British efforts to re-write and expunge history the journalist Iain Cobain has studied something called “Operation Legacy” which has been described as “an orgy of destruction”, carried out across the globe between the 1940s and the 70s.

In 2013 he discovered that the Foreign and Commonwealth Office had been unlawfully concealing over a million historical files at a highly secure government compound at Hanslope Park in London. The files contained millions of records stretching back to 1662, spanning the slave trade, the Boer wars, two world wars, the and the Cold War period. More than 20,000 files concerned the withdrawal from empire. This was a goldmine of deceit and cover-up. He discovered that when the files concerned were eventually transferred to the UK’s National Archives – where they should have been all along – it became clear that enormous amounts of information had been systematically destroyed during the process of decolonisation.

Cobain writes:

“Beginning in India in 1947, government officials had incinerated material that would in any way embarrass Her Majesty’s government, her armed forces, or her colonial civil servants. At the end of that year, an Observer correspondent noted large palls of smoke appearing over government offices in Jerusalem. As decolonisation gathered pace, British officials developed a series of parallel file registries in the colonies: one that was to be handed over to post-independence governments, and one that contained papers that were to be steadily destroyed or flown back to London. In Uganda in March 1961, colonial officials gave this process a new name: Operation Legacy. Before long the term spread to neighbouring colonies, where only “British subjects of European descent” were to be involved in the weeding and destruction of documents, a process that was overseen by police special branch officers.”

Particular effort had been taken to obliterate the truth about the torture and murder of rebels in Kenya; the brutal suppression of rebellions in Cyprus and later Aden; massacres in Malaya; and the toppling of a democratically elected government in British Guiana.

“Instructions were also issued on the means by which papers should be destroyed: when they were burned, “the waste should be reduced to ash and the ashes broken up”. In Kenya, officials were informed that “it is permissible, as an alternative to destruction by fire, for documents to packed in weighed crates and dumped in very deep and current-free waters at maximum practicable distance from the coast”.

This last month has seemed like those crates have floated to the surface, and that Operation Legacy, a conscious effort to deny our racist colonial imperial past has failed.

As Britain seems to try and immerse itself in the past it is also overtaken by it.

But this is not just about hiding a shameful past. This process is happening now. It’s not just that the world we imagined we would be living in has changed from when we were children – the world we imagined we would be living from last week has gone too. Simple things like the security of employment, availability of housing and education are now radically uncertain. Precarity, previously the state of being of an unfortunate section of the workforce dependent on the ‘gig economy’ has now become a universal syndrome. Our precarious existence now extends way beyond our material or psychological welfare but to our health and even our existence.

So if people cling to bits of history and fragments of reality that have dissolved maybe we shouldn’t blame them, because that’s what we’re doing too.

I read that at the end of the war the Nazis destroyed a load of papers as well. I am sure other countries have done similar things when there is a regime change.

As someone with an interest in history I find this tragic.

It is also, with hindsight comic.

The ‘history’ of the British Empire may have been written rather differently if civil servants at the time had not ”followed orders ” and preserved the records . We know that the British legacy in many countries , with the surviving records , is less than exemplary . What would the story be if we knew the WHOLE truth ?

Your ‘Legacy’ much appreciated. As an 18-year old subaltern commanding an African platoon in the early 1950s during the Mau Mau campaign, I only later became aware that this was probably the last of the Empire wars. As a National Serviceman, we were given no background whatsoever on this before being given a week-end to learn the language and shoot anything that moved in the forest. It was much later that I researched the background to this infamous conflict and wrote about my personal experience. However, the whole history of the Empire project is very well described in ‘The Blood Never Dried – A People’s History of the British Empire’ (second edition, 2013) by John Newsinger. It should be prescribed reading in all schools: the press reports of the time gave a very skewed white colonial perspective.

@James McCarthy, I am in the midst of reading Newsinger’s book now, having read the first edition years ago. In his introduction to the updated version (2013) he writes of the kind of epic distortions that this article covers. But the premise that the book keeps needing to be updated should be followed by the conclusion that the British imperial project never ended, and today continues as part-slave, part-collaborator with the USAmerican empire. Newsinger’s forceful point that the mythologists of Empire are currently successful in promoting their twisted narratives should make us consider more deeply why this is still necessary, and I would argue that it is not just that some of the criminals under whose authority these atrocities were carried out are still alive and even still in power. The British imperial mode has recently been slapped down by international opinion over the treatment of the Chagossians, and there is the question of why the British military continue to recruit from the neo-imperial Commonwealth and treat these recruits with the same racist disdain as during the rest of the Empire:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p085s6kz/racism-in-the-ranks

The biggest lie, perhaps, is that the British Empire has died. Although that is not swallowed by its modern supporters, it seems. The awkward aspect for them is that the similarities rather than the differences between WW2 British imperialists and its rivals are foregrounded. Having said that, the British did a lot to restore the fortunes of various rival empires in the aftermath of WW2, not something we have been hearing a lot about following VE-day commemorations.