Scottish Independence – a Long View

Presentism is the historian’s powerful sworn enemy. Insisting on seeing the past through the lens of today’s preoccupations hinders attempts to understand the world through the eyes of yesteryear’s denizens. These dynamics are even more powerful when it comes to nationhood. Nationalism ultimately draws its strength from a sense of the national community’s timelessness and its superiority over other allegiances. Eric Hobsbawm memorably insisted that ‘no serious historian of nations and nationalism can be a committed political nationalist … Nationalism requires too much belief in what is patently not so.’[1] For Hobsbawm’s critics, this is itself dogma from an author who never ‘got’ Scotland’s distinctive circumstances.[2] Contemporary Scottish nationalism is, after all, heavily enthused by post-sovereign assumptions and comfortable with nationhood existing as one of many identities and allegiances. For over half a century, it has also been relentlessly future facing. Since Winnie Ewing’s breakthrough victory at the Hamilton byelection in 1967 announced ‘Stop the world, Scotland wants to get on’, the chief messaging of independence supporters has been one of leaving an archaic state to establish a modern egalitarian democracy. It is Britain which is most characterised by social hierarchies and crippling nostalgia.

The public history of devolution has tended towards a story of mobilisation and cultural confidence. Scott Hames has diagnosed this version of late twentieth century Scotland as ‘the dream’ which was articulated by poets and authors.[3] The Scottish Constitutional Convention’s (SCC) 1988 Claim of Right provides an important reference point through its language of popular sovereignty. The memorable insistence of the SCC’s chair – Kenyon Wright – that a parliament will be established is eminently quotable: ‘Well we say yes – and we are the people.’ However, as Hames details, it was ‘the grind’ of electoral politics and committee room battles in the Labour Party which delivered devolution in the late 1990s. A less ‘heroic’ assessment of the late twentieth century will be of much use in the third decade of the twenty first. Scotland seems to be in a similar juncture to the one it found itself in during the latter 1980s. In the aftermath of the 1987 general election, when Tory representations collapsed from twenty-one to ten MPs, devolution became the ‘settled will’ of the Scottish people and the political class, after it had been a highly divisive subject a decade earlier. In the 2020s, it is more than possible that a highly unpopular Conservative government which lacks an electoral mandate attacking the institutions of Scottish democracy will help inchoate a similar status for independence.

We need a longer run view to help us to understand what is at stake in the current constitutional juncture and to assess possible outcomes. Another Scotland is possible but just how different it can look is another matter. Hobsbawm’s assessments of nationalism contained another helpful provocation. He was adamant that nationhood’s material foundations were ‘the assumptions, hopes, needs, longings and interests of ordinary people, which are not necessarily national and still less nationalist.’[4] In a country where popular modern folk songs list places blighted by the closure of car factories and coal mines that seems hard to contest.

But there’s a longer history to the economics of nationhood than the avalanche of Thatcherism’s accelerated deindustrialization and these raise fundamental questions about what an independent Scotland could or should look like. The basic starting point is Scotland’s status as a small open economy, which is highly unlikely to change. Engagement with the global economy is what made Scotland rich by international standards. Black Lives Matter protesters have given energy to a reassessment of that history which has been advanced by scholars of Scotland and slavery such as Stephen Mullen. Mullen’s recently published research which details James Watt’s engagement with the slave trade provides an apt metaphor for how slave trading and colonialism were important to Scotland’s economic development.[5] International trade and natural resource endowments enabled Scotland to specialise in coal mining, steelmaking and shipbuilding. This took place during the period of nineteenth century liberalism and the homeland of its key economic theorist – Adam Smith – followed his logic of comparative advantage.

Modern Scottish nationalism emerged from the demise of the Scottish industrial order and the end of empire. Traditional pillars of Britishness were weakened from the middle of the twentieth century. The state expanded and took on a bigger role in economic management. As the Scottish Office grew, Scottish capital shrunk. Independently owned Scottish firms were increasingly replaced either by public ownership or inward investment. In each case this meant an ultimate relocation of control outside of Scotland, which contributed to demands for Scottish autonomy. In 1962, Lawrence Daly, a miners’ leader and home rule supporter, summarised these trends in a glib assessment: ‘Scotland, with a record of many centuries as an independent nation, becomes an economic and political backwater.’[6] Daly grasped the defensive nature of much of Scottish nationalism. The language of preservation – from ‘saving’ steelworks in the 1980s to ‘protecting’ Scotland’s NHS in 2014 – has been central to the appeal of both devolution and independence.

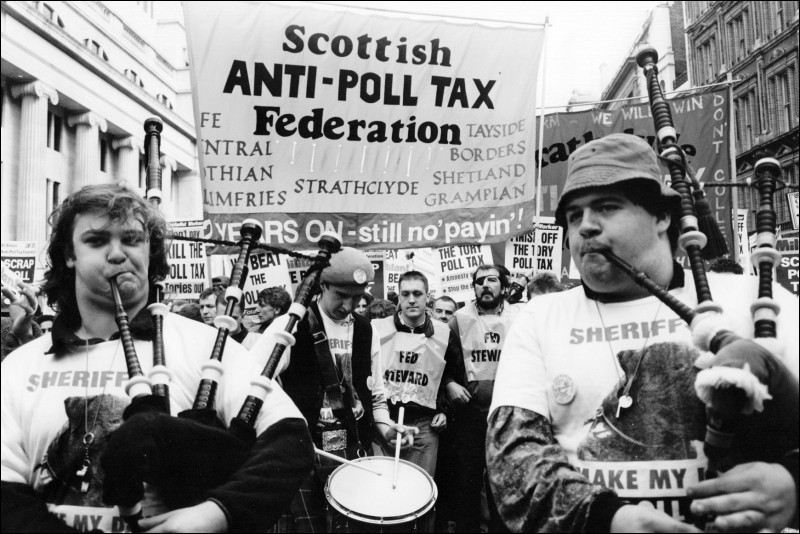

As ‘old fashioned tycoons’ exited from their formerly central place in Scottish society they were replaced by a new more technocratic elite.[7] The proliferation of government bureaucracies and the development of the third sector has fashioned an administrative class who govern Scotland on behalf of capital. This is a distinct situation from the UK level where more direct links with big business tend to characterise Conservative governments. These differences have sociological and political ramifications and contribute to the legitimacy that devolution and the Scottish Government enjoy as the national representatives. Nicola Sturgeon’s route to First Minister via graduation from a top rung Scottish university and working as a solicitor at Drumchapel Law Centre is an emblematic example. Sturgeon’s ability to act as a compassionate and relatable authority, which draws on her background in an ‘ordinary’ New Town household in Irvine, has been the dominant Scottish political dynamics during the Coronavirus pandemic. But Sturgeon’s position is also indicative of the agglomeration of political authority in devolution era Scotland. In the second half of the twentieth century, the Secretary of State for Scotland, the Scottish Trades Union Congress, the Kirk’s General Assembly, artists and writers and even the men’s national football acted as Scotland’s national representatives in the absence of an agreed official authority. It was also much easier for the labour movement and the radical left to take up the mantle of nationhood episodically, such as during the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders work-in of 1971-72 and the poll tax non-payment campaign of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

These were relatively exceptional moments. The radical left contributed to the politics of devolution but were never able to wrestle leadership from small c conservatives. Labourism’s esteem for parliamentarianism, principled moderation and unease with unconstitutional action was central to the road to Holyrood and to Scottish political culture in a more diffuse sense. Parliamentary socialism has been displaced by a parliamentary nationalism that was consciously crafted in its image. George Kerevan’s recent assessment begins from a similar premise, emphasising that like the labour movement beforehand, the SNP is dominated by a cautious leading stratum with class interests in restraining its more radical working-class supporters. Kerevan tends towards painting the SNP’s past in the most optimistic light possible from a socialist perspective. Gordon Wilson is remembered as the pirate radio host who defied the British state and the party’s vote for a strategy of civil disobedience to oppose industrial closures at the 1981 conference is also referenced.

But the utter failure of the ‘Scottish Resistance’ campaign doesn’t’ feature in Kerevan’s article. Neither does he mention Wilson’s opposition to this approach as leader nor the expulsion of the left-wing 79 Group who advocated it. Wilson’s autobiography discusses the conflict in terms that parallel the Labour Party’s ‘modernisation’ during the 1980s and Kinnock’s purging of the Trotskyist Militant Tendency. In relation to the Scottish Resistance campaign, he starkly recalled ‘I knew the Scottish people had no stomach for a fight’ but conference delegates had voted for a policy that left the party ‘lumbered with a policy of civil disobedience.’[8] Wilson gladly concludes that by the late 1980s, the party was ‘once more a member (if a radical one) of civic Scotland’ and one that was committed to a ‘centre-left’ brand of ‘social democracy’.[9]

These set the contours of gradualism that have dominated the SNP in recent years: independence in Europe, support for extending devolution and aversion to unconstitutional roads to independence. One of Wilson’s former left-wing opponents – Kenny MacAskill – summarised that transition during the SNP’s conference debate about NATO policy in 2012. MacAskill referenced his history of attending anti-nuclear and anti-war protests, concluding, ‘I’m tired marching. I want a seat for our government in the situations of power.’[10] MacAskill’s binaries between the streets and the institutions and between the powerlessness of protesters and the power of states are central to the political sensibilities of Scotland’s political class. The desire for ‘a seat’ at the table also communicates how thoroughly embedded multilateralism is to Scottish nationalism. International recognition is central to all contemporary nationalisms. But in its Scottish variety, nationhood is confirmed less by the exercise of exclusive sovereignty than through the joint agreement of order between nations. This of course speaks to the sensibilities of a nation where the last four centuries have been dominated by how it negotiates the competing demands of autonomy and integration.

These dimensions are central to any vision of what an independent Scotland will look like. The dominant case for independence rests on prolonged electoral divergence and the imposition of the Brexit project on a nation that didn’t vote for it. This makes it difficult to envision a significant current of pro-independence opinion coalescing around a harder form of economic nationalism. There is also a certain amount of virtue making from necessity when it comes to the future economic model of a small nation highly dependent on manufactured imports. Environmentalism may be an important wrench through which the pro-independence left could popularise demands for the exercise of sovereignty over Scottish resources. Emergent cultural divisions and the articulation of a majoritarian nationalism have not led to significant fissures of a more conventional left and right form. Currency will be central to determining the extent of economic autonomy that is possible. A detailed and credible plan for an independent currency needs to be set out soon if it is to be part of the debate. With the pound potentially less credible than it was in 2014, the euro could become a more tempting option for some within the SNP, but currency is an emotional as much as a question of economic forces.

The soft Yes voters who have turned towards independence are correctly judged to crave stability by the SNP leadership. Most of them are not in the small minority who have reluctantly concluded that roads of radical transformation that lead through the British state have been cut off, who this author numbers among. Returning to Wilson’s terms, it’s hard to argue the people of Scotland are more ‘up for a fight’ now than they were in 1981 when at least some sections of the organised working class were prepared to engage in long hard defensive battles. Just as the experience of mass unemployment, industrial closures and the indignities of the poll tax fuelled support for devolution, so precarity, Universal Credit and xenophobia of the UK government stimulate independence’s poll lead. But ‘popular’ mobilisations did not provide the mechanism for devolution. Even as big a rupture as Coronavirus has principally resulted in a few per centage points in polling. Events in Catalonia also demonstrate the power that the central state exercises when it comes to legitimating constitutional change and international recognition. These factors reinforce the gradualist strategy and make the further incremental accumulation of support for independence likely whilst also postponing its achievement.

Presentism may be historians’ favoured villain, but historicist fatalism is the enemy of activists. Measured pessimism is an inconvenient friend though, especially in a context of inflated but unsubstantiated optimism. Discussions of Scottish independence often acquire metaphysical qualities, by stimulate the imagination of the future or provoking fear and dread. But hard-headed realism will be required to gain any sway in the discussion of what a new Scottish will look like. Its contours begin with the realities of a small nation on the North Western periphery of Europe. Political culture is perhaps more malleable than engrained patterns of political economy, but nevertheless, the power of the gradualist logic of parliamentary nationalism cannot be denied. It also embeds a powerful self-reinforcing logic. Whilst socialists often wish for wars of manoeuvre, we know that longer and protracted wars of position are often the experience of historical periods.

[1] Eric Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990) p.10.

[2] David McCrone, ‘Getting Scotland: Red-Reading Eric Hobsbawm’, Scottish Affairs 83 (2013) p.1.

[3] Scott Hames, The Literary Politics of Scottish Devolution: Voice, Class, Nation (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020).

[4] Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism, p.10

[5] Stephen Mullen, ‘The Rise of James Watt: Enlightenment, Commerce, and Industry in a British-Atlantic Merchant City, 1736-74’ in M. Dick and C. Archer-Parré (eds.) James Watt (1736-1819): Culture, Innovation and Enlightenment (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2020) pp.39-61.

[6] Lawrence Daly, ‘Scotland on the Dole’, New Left Review 17 (1962) p.22-23.

[7] Chris Harvie, No Gods and Precious Few Heroes: Scotland’s Twentieth Century (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1993) p.151.

[8] Gordon Wilson, SNP: The Turbulent Years , 1960-1990: A History of the Scottish National Party (Stirling: Scots Independent, 2009) p.207.

[9] Ibid, p.229.

[10] James Cook, ‘Daily question: What is NATO and would an independent Scotland join it?’, BBC News <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-29047833>.

Your article is unnecessarily ‘heavy’. Following the points you were attempting to make would have been made easier if you had used more commas. I had to give up after ‘inchoate’ …..did you mean inculcate? Communication is a wonderful thing, when it happens You can just assume I’m thick if you like, but I won’t be the only one not getting the point, or to the end of your article.

Quite so, Morag Burton.

I enjoyed the historical information but it was not clear what you are trying to say.

I THINK you are saying we need to be patient and MAY get Independence at some point in the future when Westminster screws up even more.

You also seem to be saying that we need to think what independent Scotland will look like

He’s arguing for gradualism and still retains hopes the UK is capable of delivering social democracy.

Ah, Gradualism is arguably viable if you are under 70, but the UK delivering social democracy? Excuse me a pig just flew past my window.

Enough of this. Fed up with conjecture, doubt, and fear. With half attempts. I’m just sick of always getting a kicking. From left, from right, from centre, from soft No’s, from maybe Yes’s. Time to get on our feet and be ourselves. We couldn’t do any worse. We have the resources.

Except for self-belief, which this article tries to run down.

There comes a point when you just have to stand up and get on with it. What’s to lose?

This article is a protracted essay in miserable-ism and the notion that nothing can ever really change because everything is already pre-determined. I’m fed up listening to this stuff. Fed up being stuck and talked down to.

I became a nationalist at 17 because I realised very early on in my life that I was not a racist. Just as I argued passionately for the right of black peoples to govern themselves and that they were equal to anybody else in terms of their intellectual capacity, rights and talents, I soon applied this to Scotland and to my own people, the Scots.

For us, ‘nationalism’ is simply the belief that we’re as good as anybody else and just as capable of running our own country. It’s about living your own life, and not having somebody else’s decisions foisted on you.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YiTYKjKg73s&feature=emb_logo

This guy speaks for me

If this is the best case scenario for Scottish independence, somebody wake me when it comes please, because I’ll be in my bed, (or maybe I’ll just go off to do something more interesting with my life in the meantime)…

Question: Why would the government which tried to prorogue parliament, which ran and won a Brexit campaign funded by dirty money and by propagating never-ending lies, and which is currently ripping the heart out of the UK Civil Service (an old boy’s racket, but, nonetheless, serious professionals more or less) give a toss about precedent, the democratic deficit and the sovereign will of the Scottish people? The Claim of Right? What’s that then, an island malt? Why do commentators keep telling us the Tories will have to grant us a referendum, when the Spanish State refused to do so in the case of the Catalans, for example, gifting Boris and Gove a very handy precedent? Any answers welcome on a postcard…

Also this: the referendum Scottish democracy was and is owed following the contrasting results of the Brexit vote in Scotland and England was not the SNP leadership’s to give away, or hold back on, or wait till the polls changed to cash in on.

It was and is a matter of European of democracy, no more no less… I don’t know about other people, but I am very angry about being dragged out of the EU without a second vote, an each day that passes by, I get angrier. But no one in the SNP seems to be that bothered…

Finally, the firewall to a full English Brexit always was and still is Scottish independence within the EU. If we had won the referendum back in 2014, Brexit England would have been left reeling to such an extent that the campaign to exit the EU would have deflated like a punctured balloon…

It wasn’t a “best case scenario for Scottish independence” but some history of the home rule movement (?)

It will take real anger to achieve independence. Not managerialism.

It will take a combative spirit most certainly, and it will take a bit of nerve and a bit of fight and a bit of mental toughness…and it will take a capacity for risk which Murrell and Sturgeon do not appear to have.

If the SNP leadership does not have the strategic nous to see that, until Boris Johnson has his trade deal with the EU, he is weak, he is vulnerable, his job is on the line, then I cannot see they have what it takes to deliver independence.

If the SNP wait until Boris has his trade deal signed and sealed and on the front page of all the papers – to triumphant fanfare, “he pulled it off” and all the WWII comparisons which will inevitably follow about old doughty British values and fickle Europeans – then I don’t think we will see another referendum in ten or twenty years.

If, on the other hand, the SNP govt called an advisory referendum for St Andrews Day, and we got a big number for YES – anything from 55% upwards – then that could play very nicely into the last few weeks of the trade deal negotiations and pull the rug out from under Boris’ feet…

They said we had to wait for the polls. The polls are at peak SNP / YES more or less, maybe there are a few more points to be squeezed out for YES, but 25-30% of Scots are ideologically Unionist and another 20% don’t vote, so 55% where we are now is about as good as it gets…

Why wait till May? Somebody tell me why Johnson is going to agree to a referendum which the Tories have refused to grant us not once but twice?

I’m very open to ideas for resistance, protest and NVDA but …

If the SNP called an advisory referendum on St Andrews Day, what would happen if a) only Yesers took part as everyone else claimed it was illegitimate and b) it had no standing internationally.

Why would that bring more pressure? I dont understand the reasoning.

Why would only YESSERS take part? It will be a fully legal advisory referendum, called by First Minister Sturgeon after a major pro-European keynote speech in which she reminds European member States, and all Scottish voters, that Scotland did not vote for Brexit and it is incumbent on her as First Minister to let the citizens of Scotland make their voices heard before the end of the Withdrawal Period, and in the face of Johnson’s obstinate refusal to agree to a section 30 order, by answering the following question:

Do you believe Scotland should become an independent country in order to rejoin the EU? YES or NO.

That would be the question, or something like it, it must be explicitly tied to EU membership I feel. At the least, it would be a protest vote and a rallying point. At the most, it might offer a massive majority for YES, whether Unionists take part or not, and put pressure on Johnson and perhaps lead to independence – London might just cave in.

The Europeans would love it and their press would be up here like a flash.

The Catalan case is completely different. The Spanish Constitutional Court had ruled that their referendum of 1-O 2017 was illegal, months before it took place. So, Catalan Unionists could justifiably say that they weren’t prepared to take part in an illegal referendum. It was because of that Constitutional ruling that Rajoy sent 15,000 Guardia Civil to prevent it taking place. That is nothing at all like our case. An St Andrews Day advisory referendum would not be illegal.

Also, and this is very important to remember about the Catalan case, Junts Pel Si – the pro independence platform of several parties (all the independence parties except the CUP) didn’t have a referendum on independence in their manifesto! Remember, Artur Mas declared the 2015 Catalan elections a plebiscite on Catalan independence. He lost that plebiscite in terms of votes cast (the popular vote) but Junts Pel Si ended up with a one seat majority in the Catalan House which they then used to pass a raft of unconstitutional laws “disconnecting” Catalonia from Spain, in principle, in a period of no more than 18 months.

As it transpired, they did not have enough time to fully “disconnect” Catalonia from Spain, and all the laws they had passed were declared null and void by the Spanish Constitutional Court along the way, so that in the end they resorted to calling a referendum: an improvisation…The Catalan case has nothing to do with our case at all.

And we would not be looking for international recognition from anybody. We would be seeking to open negotiations with London, and an amicable divorce, perhaps with the proviso that it be subject to a confirmatory referendum in Scotland to take full effect (though perhaps not)…

PS: You must remember, Bella, that the Europeans are seriously pissed off with Boris Johnson and the English Tories. They are horrified by Brexit, and quite rightly so, and see it as a threat to the whole EU project, which it is. This feeling is likely to become more exacerbated as we move towards the business end of the trade negotiations.

So, the people at the highest level of European politics will be sympathetic to a second referendum in Scotland. They cannot actively encourage it, but they are very sympathetic to it. Again, the Catalans were a headache for the rest of the EU member States at the highest level. So, once more, this comparison with the Catalan situation holds no water… and in terms of Spain, Gibraltar is a constant thorn in their side, and Sánchez is making a real play for joint sovereignty which an independent Scotland would support I presume…

The key thing is to take the initiative. Independence is not going to be delivered to us wrapped up in a box with a big fancy bow like Ian Blackford thinks it is…

“The key thing is to take the initiative. Independence is not going to be delivered to us wrapped up in a box with a big fancy bow like Ian Blackford thinks it is…”

I agree. Completely.

I agree with everything you say vis a vis Catalonia and Spain but I think that No voters would boycott such a poll and attempt to undermine its legitimacy. I dont think that’s terminal but I do think that’s a reality.

I think you must pitch it as a Scotland in the EU election….that way you smash the Unionist/Nationalist divide and hopefully create a whole new constituency for independence….

As for Unionists not voting, I wouldnt bet on that at all. The sands are shifting and with one or two big name Unionist converts, then maybe the floodgates open…

It’s not just about being outside the EU as it would have been with Theresa May. It’s about the nightmarish Britain Boris and Cummings have in store for us. The vast majority of Scots despise Johnson and all he stands for. Maybe as high as 8 or 9 out of 10….

But the question must be put to them…

Congratulations.Essays like this give hope for the future.