Some of the best female novelists working today are Scottish. You’ve just never heard of them

A few weeks ago The Times demanded to know why Scotland had never produced a “break out” young female novelist like Sally Rooney. Sure, it opined, Scotland gave us Ali Smith, but that was ages ago. She’s no longer young. Where are all the decent, young, female, Scottish novelists?

Predictably, Scottish literary Twitter exploded – just as The Times’ click-bait gremlins hoped it would, but also with good reason. The article’s central premise was false from the start; its author’s concern for the state of Scottish women’s writing so obviously bogus. Anyone who knows the world of contemporary fiction even a little knows that some of the best female novelists writing today are doing so from north of the border. You’ve just never heard of them.

There are a few reasons for this. One: it’s harder for women and non-binary writers to find readers than it is for men. Many of us have always known this, but now – thanks to a growing data set provided by organisations like VIDA – we can prove it. Two: to be based in Scotland is to be routinely passed over for best of lists, major awards and – as The Times acknowledges – the much-hyped six-figure advance. It is a truth universally acknowledged that publishing, reviewing and literary taste-making in these islands is persistently London-centric. But – crucially! – three: because of these things, Scottish women are free to write fiction that doesn’t conform to the expectations of a publishing mainstream.

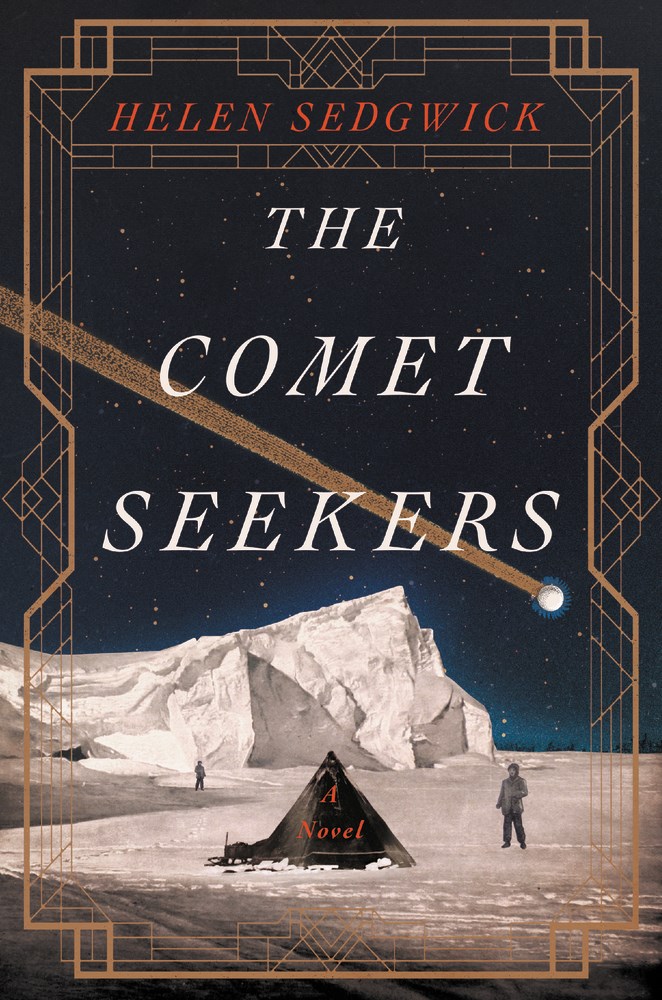

The first person I thought of as I read The Times article was Helen Sedgwick. Helen’s debut novel, The Comet Seekers (Penguin, 2016) is expansive and genre-defying: part historical novel, part ghost story, part romance. Her second, The Growing Season (Penguin, 2017), draws on Sedgwick’s background as a research scientist to examine the possible future of conception, gestation, childbirth and well, what it means to be human, really. Her latest book is the spooky police procedural When The Dead Come Calling (OneWorld, 2020), a new Hound of the Baskervilles for the Brexit era. Is there any topic Helen Sedgwick won’t tackle in her fiction? If so, she hasn’t found it yet.

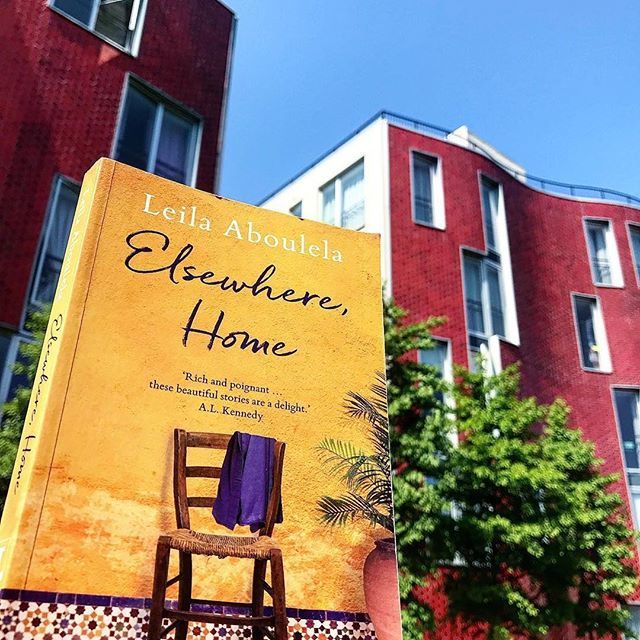

I also thought of Leila Aboulela, the Aberdeen-based author who has worked consistently to build an oeuvre of critically acclaimed fiction since 1999. Her short story collection Elsewhere, Home (Telegram Books, 2018) won the 2018 Saltire Fiction Book of the Year Award, and her debut novel The Translator – first published in 1999 by Grove Press – was included in the New York Times’ 100 Notable Books of the Year, longlisted for the Orange Prize and shortlisted for the Saltire First Book Award. It has also appeared in numerous editions worldwide: if Aboulela is not a “break out” novelist, I’m not sure who is.

Indeed, there are few female novelists more “break out” than Scotland’s own Gail Honeyman, whose smash-hit novel Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine (HarperCollins, 2017) made her a household name. Eleanor Oliphant won the 2017 Costa Debut Novel Award, Debut Book of the Year at the 2018 British Book Awards, and has been optioned for film by Reese Witherspoon’s production company. Presumably, this incredible success was ignored by The Times because of its article’s strange focus on youth – Honeyman was born in the dim and distant year of 1972, after all.

A couple of Scotland’s contemporary female novelists, Jenni Fagan and Kirsten Innes, were mentioned, though the article failed to note that both have just published new novels. Fagan’s The Panopticon (Windmill) won its author a place on the Granta Best of Young British Novelists list in 2013 – her latest book is The Luckenbooth, newly released by Penguin. Innes, meanwhile, won the Not The Booker Prize for her 2015 novel Fishnet (originally published by Freight), and her brand new book Scabby Queen (Fourth Estate) is already garnering rave reviews.

![]()

![]()

I side-eyed the fact that Fagan and Innes’ books were quickly dismissed as “page turners” – an expression usually reserved to denote (and sometimes demean) genre fiction. Naturally, The Times article overlooked genre entirely, though some of Scotland’s most exciting fiction writing is being done in crime, SFF and horror. Denise Mina’s The Long Drop (HarvillSecker, 2017) is a perfect example of a female Scottish novelist working at the height of her powers. Louise Welsh’s The Cutting Room (Canongate, 2011) is another. Meanwhile, Kirsty Logan has collected The Scott Prize (2013), a Saboteur Award (2014), the Polari First Book Prize (2015) and a Lambda Literary Award (2016) for a growing body of work that continually pushes the boundaries of fantasy, horror and magic realism.

These are only a few examples: I’m running out of space to talk about Mary Paulson Ellis, whose novels The Other Mrs Walker (Pan Macmillan, 2016) and The Inheritance of Solomon Farthing (Pan Macmillan, 2019) did in fact net one of those coveted six-figure deals. There’s also Natalie Fergie, whose debut The Sewing Machine (Unbound, 2017) has sold over 125,000 copies and sold rights to Germany, The Netherlands, Greece and Russia. If your tastes run a little more avant-garde, there’s Ever Dundas, author of the cult hit Goblin (Freight, 2017), another Saltire award winner; or Helen McClory, author of several works of fiction including On The Edges of Vision (404 Ink, 2018) – another Saltire award winner. I haven’t yet mentioned Janice Galloway, Elizabeth Macneal, or Zoe Strachan – but you get the picture. Contemporary Scottish literature is in rude health, thanks in huge part to the work of its female fiction writers.

We should question the intentions of anyone who suggests otherwise.

I often find it strange how Scottish Nationalist consistently insist how separate and unique Scottish culture is from England and are fiercely protective of the cultural sphere (against the English) yet simply assume England should somehow be enthralled by them when they so choose? Why should ‘England’ another country publish another country/ cultures books (Scotland doesn’t) or hand out prizes in their awards (again Scotland doesn’t – the ‘English’ Booker prize is open internationally but the Scottish Saltire Prize is exclusively Scottish)? In fact Scottish prizes, awards, funding and publishing is almost exclusively Scottish, unlike in pluralistic England.

Yet more tiresome selective Scottish nationalism when it suits. Instead of complaining about English people not caring about a country that at every opportunity disparages it, why not develop the Scottish publishing industry instead given – no one is stopping anyone, certainly not the English?

Can’t blame the English really for prefering their own culture!

After all, why should working class, black, asian and other Londoners and other areas loose out in favour of the mostly middle class from another country? American, Australian, German, French, Canadian, South African … in fact all nations preferentialise their own output. Why shouldn’t England? Don’t need independence to do this at all.

In fact, wasn’t it one of the founders of this site that called for a ‘social audit’ on the English in the arts – (not a class audit as everyone knows).

Have you been on the sauce?

Insomnia and a deep irritation with hypocrisy.

The Orange Prize is UK (actually English) prize.

The Granta BRITISH (English) prize also! Clue is in the name Scottish nationalists!

Actually, publishers in Scotland have an enviable record of publishing work from outwith their parish; Canongate in Edinburgh and Vagabond in Glasgow immediately spring to mind. In this respect, we’re no better or worse than publishers in England; I’m a huge fan of Istros, for example, which works out of London and publishes translated work from mainly Balkan writers.

Anyway, I think Claire’s point is that female writers based in Scotland don’t enjoy the same celebrity than male writers – and especially those based in England – do, which can be liberating because it means they don’t have to use their writing to feed that celebrity and can instead focus more exclusively on its creativity, which is a good thing even if it doesn’t pay as well as celebrity.

The point was about ‘Scottish writers’ being dismissed by an English Newspaper. So what. It’s not your country! And * all the prizes she mentions are *English prizes that and only Scottish by virtue of the union. And why should the ‘London centric’ publishing industry give a monkeys about foreigners in Scotland? As opposed to other foreigners? After all this is the nature of Scottish ‘nationalist’ culture.

Fine. Just be consistent.

I read it as an article that was seeking to raise awareness of some of the splendid, but largely unremarked, writing that’s being produced by women writers based in Scotland today. The writer of the Times article seems to be unaware of this creativity; she stands corrected. It didn’t seem to me to be a particularly anti-English piece; more a case of setting the record straight and giving those splendid writers a plug among BC readers.

Indeed, and non of the awards mentioned by Angus use the criteria he suggests (ie based on ethnicity or nationality) – and the writers being celebrated here are ‘writers based in Scotland’ and that is what is being celebrated. None of their work is explicitly ‘political’ – all of it is fiction.

The compliant about the London-centric perspective of many literary awards is not confined to Scotland. Anyway, all of this is just a tiresome digression from celebrating some of the great writers here – to score cheap and wholly erroneous points. Why not buy and enjoy one of the books?

Angus (?): The point was that the Times, in it’s usual crap manner asked where Scottish female writers were. As if they don’t know, or maybe just showing the usual ignorance of anything Scottish. So, WTF are you ranting on about. Sounds simple enough to me. What’s your problem?

I think you’re a bit confused.

This has nothing to do with nationalism.

Why not? the article criticises English institutions for not paying enough attention to Scots? But the whole premise of Scottish nationalism is to divorce itself from those very communal British instiutions. It’s absurd. And the double standards are also absurd. Can you imagine someone ‘south of the border’ writing the same? Fine nationalist need to own their nationalism whole sale.

The whole article ‘north of the border’ attacking and English newspaper … about how ‘London centric the English publishing industry is. Why? England is another country. Why even mention it? Whyshould Scots assume preferential treatment over say other foreigners like Danes or Nigerian in the ‘London centric English’ publishing industry?

I don’t get it. Are you nationalist or not?

Angus, have you read the original article that this is responding to?

I think it was by the Glesca-based writer, Gabriella Bennett.

The article appeared about a month ago. I don’t have that issue any longer; it’s long-since been shredded for compost. I remember being a bit non-plussed by it at the time.

Maybe it will still be available online.

1) Bella C is an overtly nationalist site (fine). 2) Scottish nationalists aggressive seek difference with English culture (fine ) 3) The article frames it as Scottish writers not getting recognition (fine, I’m sure they re brilliant) 4) But she states ‘in these Islands’. Ergo, recognition in England 5) She talks about London centric publishing (in England)

The point being if Scotland can be aggressively nationalistic culturally then why can’t England also? Why even complain and seek recognition in other poeple’s country in a way that wouldn’t be tolerated in Scotland?

And it’s a long running theme … Kelman moaning about the English, or the booker prize when the criteria clearly states ‘a novel in English’ But Kelman writes in foreign Scots! (as nationalist consistently insist.

It’s the double standard. I’m helping with your cultural purity and road to Indy by othering Scots in the way Scotland does English culture! Everyone’s happy!

Well, I agree that publishing, reviewing and literary taste-making in these islands [i.e. the British Isles] is no longer London-centric. In that, Claire is just plain wrong.

It used to be, before the digital revolution in the publishing industry. But the means of production in that industry have since been democratised as a result of that revolution, and taste-making has become less about marketing and more about what world-wide ‘interest communities’ of readers and writers, who find one another on the internet, and who largely produce and consume their own content in prodigious amounts, enjoy sharing.

Never before has publishing been so dispersed or catered for such a plurality of tastes and interests. Indeed, the digital revolution has made a bit of a nonsense of the whole idea of ‘national’ literatures and cultures. We’ve beyond those; we’ve gone global.

Of course, you could, like one auld nationalist did at the 1962 Edinburgh Writers Festival, dismiss any artist who doesn’t identify with a nationalised cultural tradition (‘Scottish’, ‘English’, or whatever) as ‘cosmopolitan scum’. But who would care?

The thing is , 90% of this site’s output pits itself against Britain and in that it pretty much means England so it will shoe-horn that into anything. But in my experience this isn’t even a nationalist trope, but simply a Scottish one born of centuries of conflict with England, a bigger and more powerful neighbour. What unites England and Scotland is a fierceness both mental and physical so there is little chance of a meaningful accommodation, even after all these years. It has been stated by some that one road to independence is to piss England off so much with the endless grievances that people south of the border will finally throw up their hands and so please just go. Indeed quite a few English said this in 2014 but were disappointed by what was ultimately Scottish weakness leading to the obvious conclusion only Scotland can bring about its independence by enough people actually wanting it. On these pages frustration has been shown at those Scots who love to moan about England but voted No to independence.

One of the striking things when visiting pretty much anywhere in Scotland is how everything ‘Scottish’ is paraded at every turn and this is not true to the same extent in England – nationalism is ‘good’ in Scotland but ‘bad’ in England.

I see none of this changing ever really so it has to be accepted that BC is what it is and instead enjoy some of its excellent output though I also think it can show hypocrisy. Much of this born of frustration at not being able to persuade people in Scotland of the worth of independence, a cause I am slowly but surely thinking is the only way forward for both nations.

Just to complete (and close) this utterly ridiculous conversation- I’m told that Claire – the author (who I didn’t commission and don’t know) is herself English.

And Gabriella Bennett, who wrote the Times article, is fae Fife.

Exactly. No more Scotch Settlers or Colonists in England. Bye.

Well done. Great article.

Kind of hilarious that it’s followed by such a silly thread, above – the author was responding to a daft provocation, which happened to specify Scotland (for some weird reason), so in her response she focuses on Scotland, naturally enough, and whose literature she clearly knows very well.

I’ve picked up a few recommendations, and am persuaded that there’s a lot of exciting writing by women taking place.

I agree. I’ve been hoping to read more female and non-binary authors. The whole point in making a point of focusing on any minority group is because we want to push back against the absurd male dominated and chauvinistic industries. The Times is in my opinion a highly elitist rag so I don’t care for their opinion. If we look at the history of published uk authors we would see the percentage of white, male, english authors is way higher than the percentage of that same demographic. Ina society where women are paid on average far less than a male doing the same job we cannot deny this bias in uk policies.

I’m glad to discover new authors of any denomination, but I am still making a point of seeking out those I feel have been brushed under the rug 🙂

Happy reading!

Thank you so much for the list of authors I’ve been making a conscious effort to discover more female and non-binary authors.

Having read a few of the comments I get the impression (I’ll leave you to guess who I’m talking about) that someone is a ‘But ALL lives matter!’ kinda person :/

Happy reading guys! 🙂