Allen Ginsberg, Iona, and the End of America

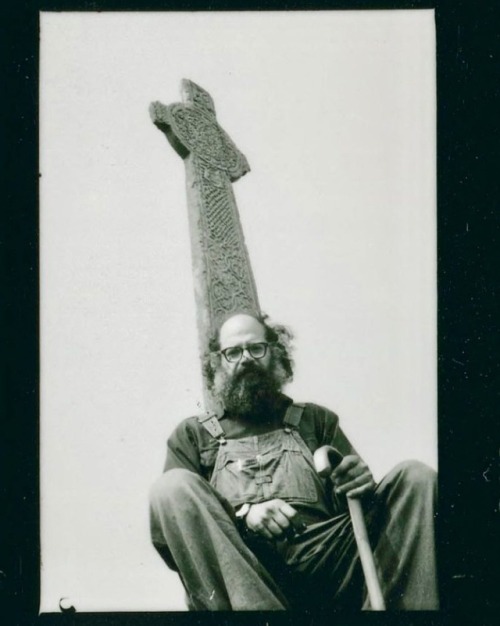

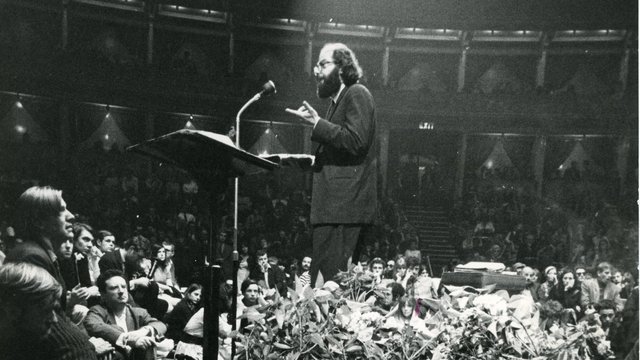

Here’s the American poet Allen Ginsberg by the 15th C Maclean’s Cross on the island of Iona in 1973. Ginsberg had met with Hugh MacDiarmid on the poets 81st birthday, in August of that year. They had both met and read in London (at the “Poetry International” in the Albert Hall) a few days previously. ‘The International Poetry Incarnation’ or ‘Gathering of the Tribes – Poetry Reading Festival’ was sometimes called the first British ‘Happening’, where beatniks met the emerging hippie culture. The seventeen poets who recited, included Adrian Mitchell and Allen Ginsberg, were not given any running order and the event ran for four hours in front of a marijuana smoking and heavy drinking crowd.

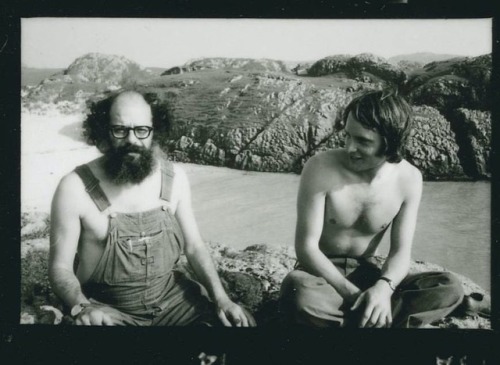

Afterwards, Ginsberg traveled to Scotland to perform readings in Edinburgh and Glasgow before going on to Iona with Scott Eden (interviewed below). They both then traveled down to England on a route via Carlisle, the Lake District, Manchester and London. Here’s vintage documentary footage of Allen’s reading at the Scottish Arts Council Building in Blythswood Square, on August 10 1973, divided into three parts.

Here was Ginsberg connecting the radical American anti-war movement, with the Iona Community, the sacred with the profane, Buddhism with Celtic Christianity; from Berkeley to Bunessan this was Haight-Ashbury meets Port Bàn. Here’s some reflection on what he was doing, why he was here and what it means about peace, leadership and protest and the times we live in.

The International Poetry Incarnation, 1973

Ginsberg was an itinerant, a peace activist, a gay Buddhist, a Jewish libertarian and a Beat Poet [and arguably a pedophile – Ed]. He was at the fulcrum of the sixties hippy and anti-war peace movement but also an international link between the US and European radical literary movements. He knew John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Ezra Pound, William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, Robert Bly, Anne Waldman, Neal Cassady and Gary Snyder.

What was Ginsberg doing in Scotland, and what was he doing on Iona?

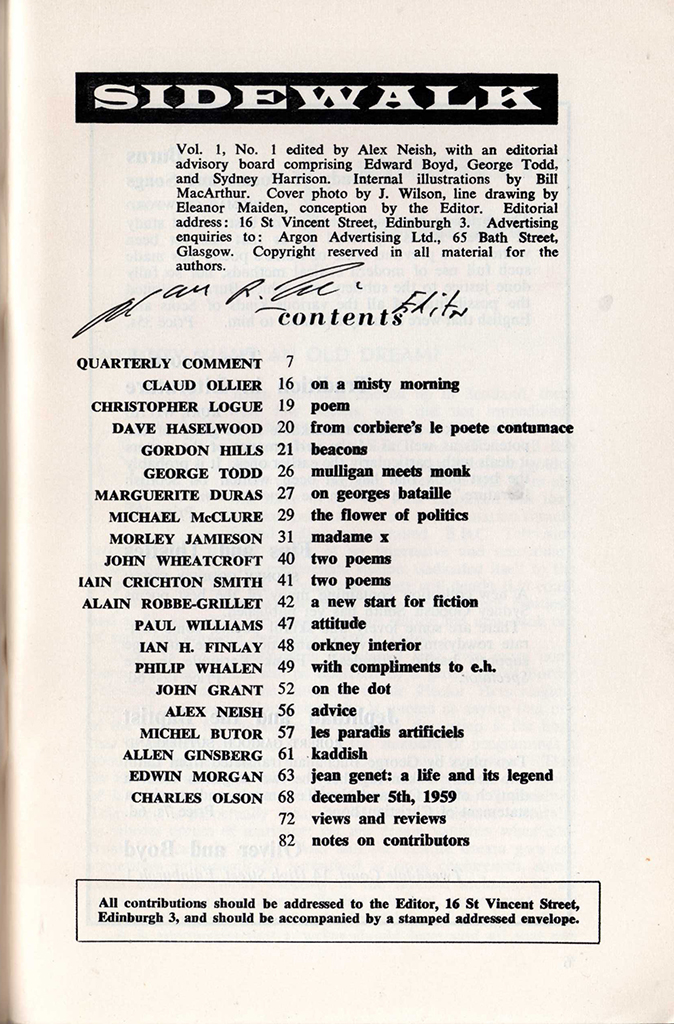

He had many Scottish connections through the radical Scottish avant-garde, the peace movement and poetry. He had come in 1962 and visited Britain again in 1967, but the connection had been started as early as the 1950s with Ginsberg promoting Burroughs to Scottish literary journals such as Cleft, Jabberwock, and Sidewalk as early as 1959.

In 1961, the radical Scottish publisher John Calder suggested a writers’ conference to the Earl of Harewood, who was then director of the Edinburgh festival. His obituary (by Alessandro Gallenzi) states: “The event in 1962 attracted some of the most prominent international authors of the time, including William Burroughs, Henry Miller, Muriel Spark, Alexander Trocchi, Allen Ginsberg, Malcolm Muggeridge, Harry Mulisch, LP Hartley and Lawrence Durrell – some of whom Calder went on to publish. In 1963, he (Calder) found a business partner in Boyars. Calder & Boyars published books by Miller, Heinrich Böll, Witold Gombrowicz, Jorge Luis Borges, Ivo Andrić, Antonin Artaud, Aidan Higgins, Elspeth Davie, Ann Quin, Ken Kesey and Yevgeny Yevtushenko, as well as continuing to commission from existing authors in his list. The publication of Last Exit to Brooklyn led to a notorious obscenity trial. The company was initially convicted, but, represented by John Mortimer, won on appeal: this signalled the end of prosecutions for obscenity in literary works in Britain.”

In 1965, Bob Dylan gave Ginsberg with a tape recorder, which Ginsberg was to use to record his thoughts and observations as he traveled throughout the United States. This was the beginning of a volume of poems and writing, a literary documentary examining contemporary America, what he called The End of America or The Fall of America. He and Gary Snyder traveled the Pacific Northwest in a Volkswagen camper bought with recently awarded Guggenheim money. He kept traveling and the tape recordings allowed him to create spontaneous writing he called “auto poesy”. Ginsberg transcribed his tapes into his notebooks and only lightly edited them. He used long breath- and thought-length lines for structure.

This was Dylan just feeding Ginsberg’s instinct for travel-writing, and the question “what was he doing on Iona” is answered really by the fact that Ginsberg was a world traveler, endlessly in search and endlessly observant and curious. This sometimes gives the impression of the Beat poets as being inconsequential: world travelers but wasted is wrong. The idea of the Beat Poets – or Ginsberg – as some kind of literary marginalia – acid-dropping beatnik lifestyle outliers – is wrong. He connected the counter-culture with the protest movement which had not yet degenerated into lifestylism or been commodified out of existence.

By the mid-sixties and beyond Ginsberg had become an iconic and influential figure. Michael Schumacher has written:

“His antiwar activism increased exponentially, beginning with his involvement in a demonstration in 1965 in Oakland—a mass protest against the war. The demonstration, largely organized by Jerry Rubin, might have been a violent confrontation had it not been for Ginsberg’s intervention. The Hell’s Angels motorcycle club threatened to disrupt the protest and beat any demonstrator in its path, but Ginsberg and the novelist Ken Kesey invited a group of the bikers to Kesey’s La Honda ranch and, after taking LSD, listening to music, and airing their differences, the Hell’s Angels agreed to back off on their plans. Ginsberg’s poem “First Party at Ken Kesey’s with Hell’s Angels” recalled the gathering; his essay “How to Make a March/Spectacle” became a primer on how to conduct a nonviolent demonstration.”

Samye Ling and the Dialectics of Liberation

From the early 70s Ginsberg had come to be heavily influenced by the Tibetan Buddhist refugee Trungpa, who had become the first Tibetan to hold a British passport and had set up the Samye Ling monastery in Eskdalemuir before marrying a Scottish woman, Diana Pybus.

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche (February 28, 1939 – April 4, 1987) was a Buddhist meditation master and holder of both the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages, ‘the eleventh Trungpa tülku, a tertön, supreme abbot of the Surmang monasteries, scholar, teacher, and poet’. His religious lineage was that of the Kargyu sect. Since the time of the Buddha, all major schools comprised three types of practitioners: the lay community; strictly disciplined monastic communities devoted to scholarship; and non-monastic ‘wild wisdom’ yogis known as mahasiddhas. They often drank a lot, exhibited ‘divine madness’ and were known as the ‘mishap lineage’. Ginsberg became Trungpa’s disciple in a relationship that mirrored that of Kerouac. We know that Allen took time out on his visit in 1973 to make a special visit to the Samye Ling centre with Trungpa.

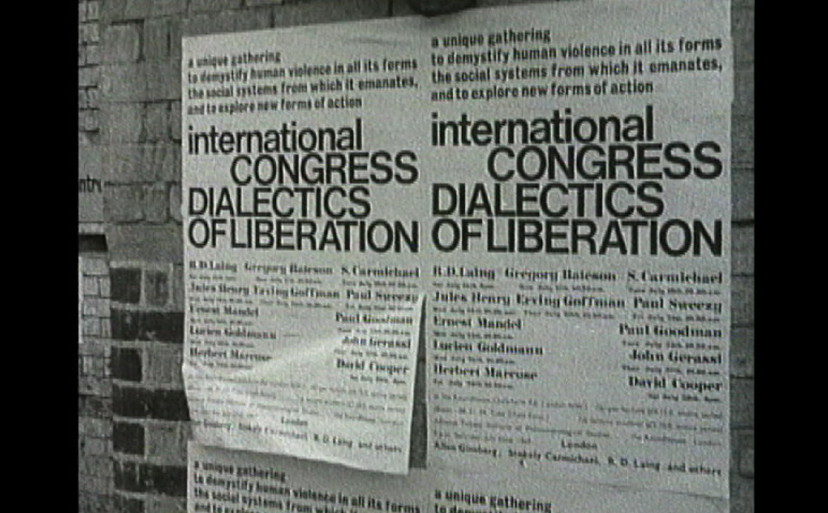

But we know Ginsberg had other Scottish connections and contacts. He had attended R.D. Laing’s Dialectics of Liberation conference at the Roundhouse in July 1967. The conference was called The Dialectics of Liberation: Towards a Demystification of Violence. The writer Daniel Hahn recounts:

“The cast-list was stellar, but eclectic – poet Allen Ginsberg; Emmett Grogan, co-founder of the San Francisco Diggers; Black Power leader Stokely Carmichael; anthropologist and proto-ecologist Gregory Bateson; Paul Goodman, author of ‘Growing Up Absurd’; Leopold Kohr, author of ‘The Breakdown of Nations’, who coined the phrase ‘small is beautiful’; and German philosopher Herbert Marcuse, author of ‘One Dimensional Man’. The Living Theatre’s Julian Beck was there too. All came to Chalk Farm for two weeks in July 1967. The Social Deviants, a proto-punk Underground band, provided the music.”

R.D. Laing – photo by Peter Davis

A later book on the conference, edited by David Cooper, described it as “a unique expression of the politics of modern dissent, in which existential psychiatrists, Marxist intellectuals, anarchists and political leaders met to discuss… the key social issues of the next decade. In exploring the roots of violence in society the speakers analysed personal alienation, repression and student revolution. They then turned to the problems of liberation – of physical and cultural ‘guerrilla warfare’ to free man from mystification, from the blind destruction of his environment, and from the inhumanity which he projects onto his opponents in family situations, in wars and in racial conflict. The aim of the congress was to create a genuine revolutionary consciousness by fusing ideology and action on the levels of the individual and of mass society.”

Hahn again writes: “Carmichael raised the roof with a fierce advocacy of Black Power and a call for a new way of fighting individual and institutional racism. Ginsberg began his talk on ‘Consciousness and Practical Action’ with a quote from William S. Burroughs’ Nova Express. The proceedings were recorded; but Ginsberg’s piece was so shocking that a woman in the vinyl pressing plant was taken ill. Bateson used his time to warn about the impending hazards of a ‘greenhouse’ effect on the world’s climate. Reporting on the conference, one commentator wrote, “I doubt if Centre 42 will see as much real creativity in 10 years as we saw in these two weeks…”

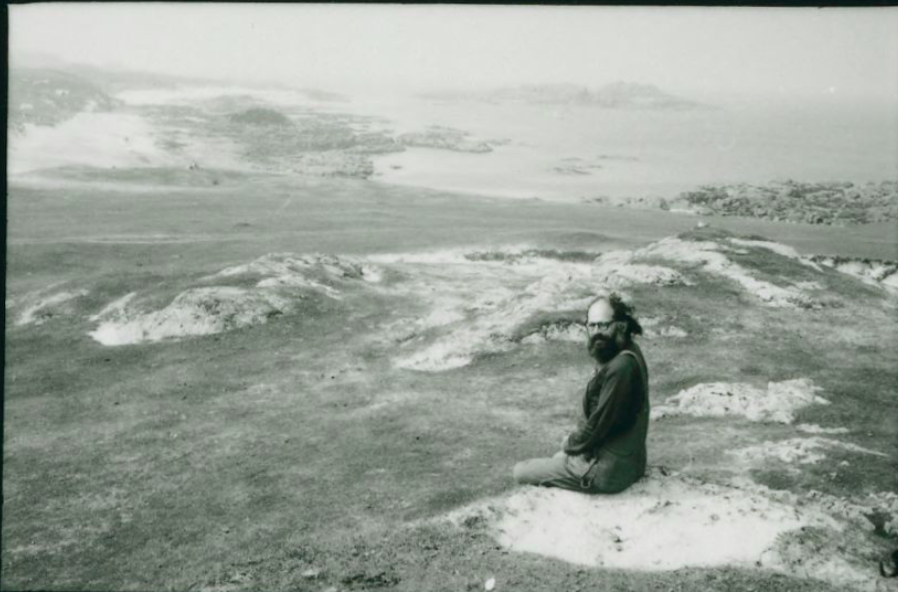

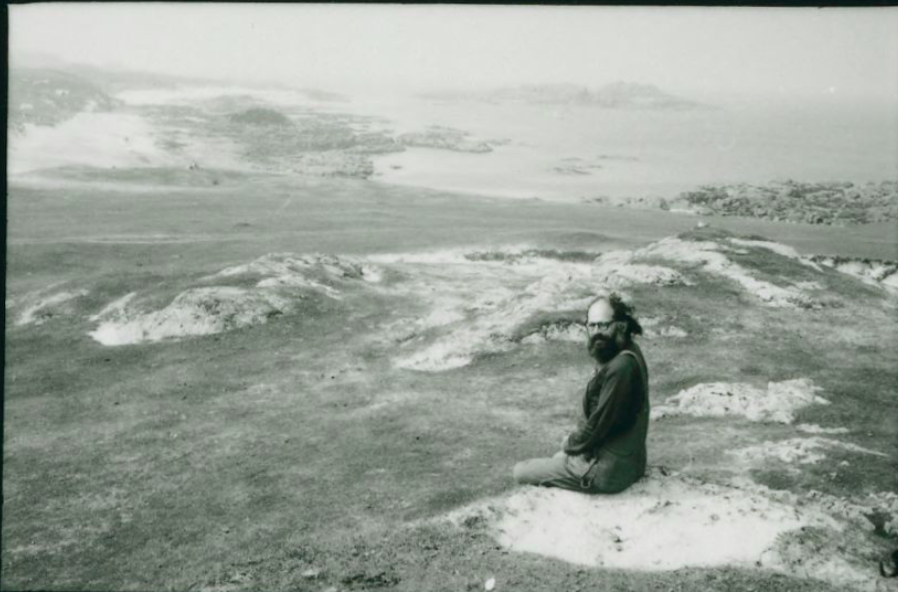

Isle of Iona 1973

Why was he on Iona?

Well, he was everywhere. His collection The Fall of America was nothing less than a staggering magnum opus, and had established Ginsberg as a literary great and allowed him the opportunity to continue traveling. As arguably, America’s best-known poet – Ginsberg seemed to be everywhere at once: here he was “After Wales Visitacione July 29, 1967” tripping on LSD, here he was describing the Russian countryside and Red Square, in Iron Curtain Journals, here he was on the impoverished streets of India, published in Indian Journals (1970). Here he is in Sidewalk alongside Marguerite Duras, Christopher Logue and Iain Crichton Smith.

He’d already established literary connections with Scotland via the early publications of his close friend William Burroughs who was published in Alex Neish’s Jabberwock in 1959. In 1960, Neish published William Burroughs in Sidewalk Issue 2. As Jed Birmingham explained in Bella in 2018:

“The editorial comment to Sidewalk sheds some light on why Burroughs was included in the magazine. In 1960, Scottish postal authorities seized a copy of Francis Pollini’s Night published by Olympia Press. The book was burned and poet Hugh MacDiarmid was questioned (the book was sent to him in the mail) by police. As a result, obscenity and censorship were hot topics in literary Scotland. Burroughs recently published by Olympia Press was a poster child for censorship issues as proven by the problems concerning Big Table and postal authorities in Chicago.”

The Scottish connections run deep – Alex Neish knew fellow publisher John Calder who he persuaded to publish Alex Trocchi. Neish has recounted:

“I persuaded John to publish Robert Creeley and then Alexander Trocchi whom we had met in Edinburgh after he jumped bail (financed by Norman Mailer who agreed) and escaped to Canada where he caught a fishing boat to Aberdeen.”

Looking west at Port Bàn

Sidewalk (1960) also featured Burroughs, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Allen Ginsberg, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley and Edwin Morgan – so the rich literary cross-fertilisation was started thirteen or fourteen years before his 1973 visit.

In the mid-1960s, Burroughs continued to be featured in the Scottish literary scene. In 1963-1964 in Cleft 1 and 2, Burroughs appeared alongside Norman Mailer, Henry Miller, and Hugh MacDiarmid showing the influence of the (in) famous Writers Conference two years before. From 1962-1964, Burroughs appeared in three issues of Transatlantic Review. Issue 11 printed Burroughs’ contributions to the Writers Conference. “Censorship” was subdivided into four pieces: “Censorship” and “The Future of the Novel” (read at Edinburgh) as well as “Notes on these Pages” and “Nova Police Besieged McEwan Hall.”

Here’s poet Scott Eden who took Allan Ginsberg on a tour from Glasgow to Iona in 1973 after meeting him at the Glasgow and before his appearance in Edinburgh:

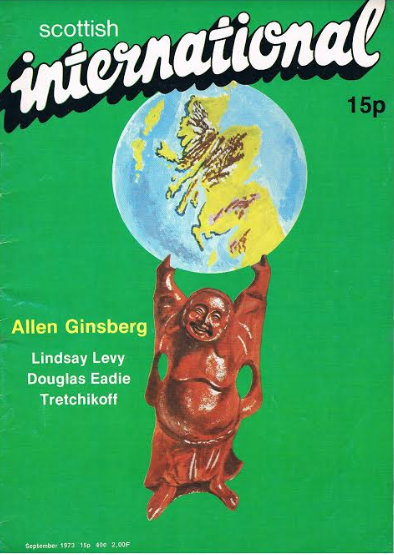

In fact it was Ginsberg who had sent Alex Neish a copy of The Naked Lunch, so that it was first published in Edinburgh in 1959. So Ginsberg was already very well connected to Scotland from the 1950s on. But a clue to why he was on Iona comes from this interview with Scottish International a month after his Iona trip.

Scottish International was edited by the poet Tom Buchan, part of Macdiarmid’s circle and member of the Iona Community. Buchan had worked in Madras, India and had a good knowledge of Buddhism and mysticism.

Buchan asks Ginsberg:

Interviewer: How do you write. Are you a typer, or a longhand, or a machine man?

AG: (seizing the harmonium and spontaneously singing) – “Well, man, years I used to write in journals and type down from that./ More recently I’ve been learning how to improvise whatever’s under my hat/ First thought is best thought as Chogyam Trungpa says about that/ First thought best thought so if you can follow your own mind/Whatever you say, chant, or sing will be acceptable as it passes into wine / Lucky if you got a tape-machine so you can find what you thought you’d lost and get it all unwinded/ First thought is best thought so improvisation may follow true/It’s the ancient bardic method . Ya know it’s not at all something that’s new/ As Homer used to improvise with his formulae, so I/ Return back to my own first consciousness before I die./And inspiration comes if you let yourself go and breathe/Thus you can sing from the heart if that’s what you’ve got the need/To do, if you’re a poet who has written down and published too much/First thought is best thought, whether written or improvised as such.”

Buchan provided the commentary for Oscar Marzaroli’s short documentary of Hugh MacDiarmid, ‘No Fellow Travellers’ (1972), the year before Ginsberg’s visit. You can view it here.

The poet and critic Mario Relich, who contributed reviews and articles to Scottish International during Buchan’s editorship, has described him as: “a flamboyant mix of hippy and political radical who dressed in military camouflage clothing in order to stand out, and someone who identified far more readily with American counter-culture than with the Scottish literary nationalism of Hugh MacDiarmid and his followers.”

Richie McCaffery writes: “Buchan continued such a mental and intellectual fight all of his life. His long pamphlet poem (published by his own Poni Press) Exorcism owes something to the ranting, incantatory style of American poets like Allen Ginsberg, but it is uniquely addressed to Scotland, its history, politics and its organised religions. Buchan tries to banish the cold god of Presbyterianism, turns his back on the Iona Community, condemns the teaching of religion in schools and pours scorn on Edward Heath.”

Ginsberg at the North End

The stark reflection is that if it looked like The End of America in 1965 or in 1968 with the generational war of the Vietnam war raging and the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy and the Siege of Chicago and the murders at Kent State University the lynchings and race violence in the south – it is as yet nothing as of the dystopian scenes being played out on the streets today. The hellscape that is Trump’s America has a long lineage and it can be traced way-back beyond the Beats writing.

But the idea of leadership – cultural or political – coming from the peace movement or from poets – feels extraordinary to our contemporary minds. It’s testimony not just to the absorption of culture into capitalism but of the degeneration of state violence and control into everyday life.

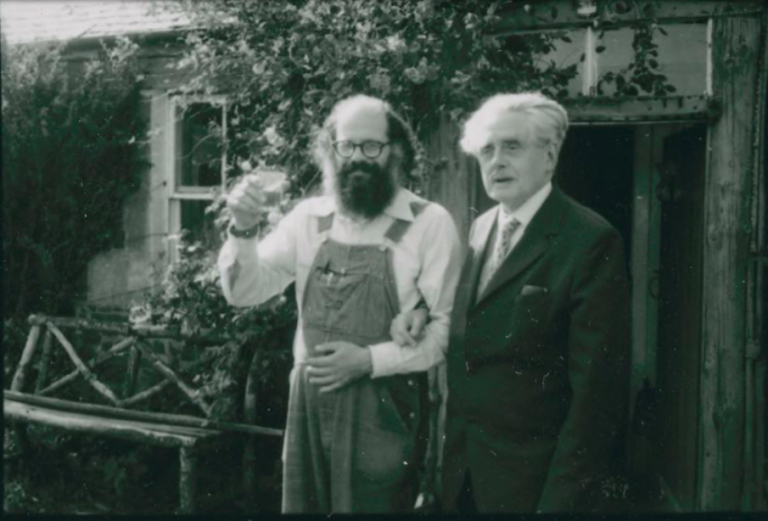

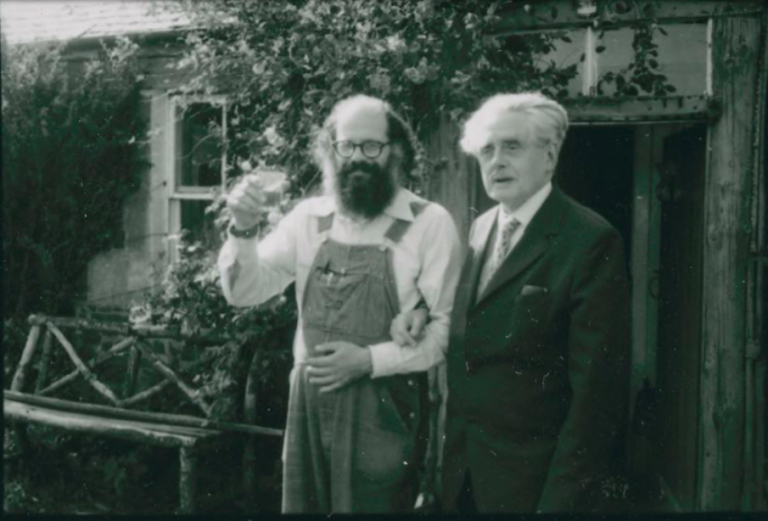

Here on the occasion of MacDiarmid’s 81st birthday, August, 1973

In The Fall of America Ginsberg attempts to contrast the raw beauty of rural North-West America with the violence, destruction, and inhumanity of the escalating war in Vietnam and the internal war against people of colour. At Port Bàn he’s looking west across the Atlantic and I wonder if he’s reflecting on that time. A year later in 1974 he was awarded the National Book Award for The Fall of America, the largest volume of poems he would ever publish.

It’s only 49 miles from Eskdalemuir to Biggar, but I’m not sure if MacDiarmid ever met Trungpa. They’d have enjoyed a dram I suspect and possibly much more.

Photo credits: Iona, Scotland, Summer 1973. (photo: Allen Ginsberg, courtesy Stanford University Libraries/Allen Ginsberg Estate)

CORRECTION

It’s been pointed out that the “Poetry International” Ginsberg and MacDiarmid were at was the June 29th, 1973 one at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, not the more famous “Poetry International” which was 1965 at the Albert Hall. Highlights were broadcast on the BBC – Ginsberg reads ‘Broken Bone Blues’, ‘In Neal Cassady’s Ashes’ and ‘What Would You Do if You Lost It’. Apologies for the error.

The connections are all amazing – I suspect that people nowadays think that many international connections are only those made since cheap flights facilitated travel, but it’s been going on for centuries. I saw Ginsberg perform with his harmonium at a college in suburban New York in 1972 – Blake poems put to harmonium music – I hadn’t a clue what he was about! I have more respect now, of course – but amazing the connections with him and McDiarmid and Trungpa and Iona and the Scottish peace movement and so many other things that when you’re 15 you don’t know what they are, esp. in a pre-social media era. Interesting also to see that the only female writer amongst 20 writers listed in Sidewalk was Marguerite Duras , amidst many now-recognized writers.

Joe Strummer of the Clash was also a huge fan of Ginsberg. Strummer was Scottish on his mother’s side. Ginsberg recorded on The Clash song Ghetto Defendant and also appeared on stage with them in the USA.

Oh!

I spent about a week with Ginsberg on Iona. He was staying at Blacks farm, I was camping nearby. We met on the train from Glasgow, and both were heading to the island. I wrote about it in my book “A Gap Life”. I remember us Sanskrit pujas in the Abbey in the wee hours, and him reciting Howl to me and a couple of sheep on the dunes above the Bay at the Back of the Ocean. Interesting times!

Thanks so much David – I thought he’d stayed there but good to hear confirmation

Absolutely fascinating article and amazing photo of Ginsberg with MacDiarmid – wonder what MacDiarmid really thought of Ginsberg’s stuff? The other thing that stuck out to me was what was Malcolm Muggeridge doing at that (radical?) writers conference in 1962? This site is full of surprises.

Tom McGrath also read that evening . . . and the line-up was, infamously even for its day, all male.

Yes, that’s a massive problem in all of this … its extraordinary looking back at it – and was commented and critiqued at the time – in fact the Dialectics of Liberation has been described by some as a competition of male egos and a competition to see who would have top guru status.

Which evening did you mean Peter, London or Glasgow?

Great to see all this on Ginsberg, but there are some factual errors that need fixing:

This piece confuses the 1973 Poetry International event with the much larger 1965 International Poetry Incarnation (yes, very similar names!). Ginsberg read at both, but the details (and photo) here relate to the more famous 1965 event. Also Ginsberg definitely did not visit in 1962. He visited the UK in 1958, 1965, 1967, 1973, 1979 (and later).

Finally, although Ginsberg’s own spelling could be erratic, he would definitely have wanted you to fix a few significant typos here, including ‘Budha’, ‘Buddism’, and the first name of his friend and longtime collaborator Anne Waldman.

Sorry to be a pain, and I really don’t mean to criticise. Clearly a lot of effort and research has gone into this piece, so I think these details are worth fixing in order that Ginsberg’s 1973 Scotland visit can get the attention it deserves. Thanks!

Thanks Luke – typos and spelling fixed – I blame covid-brain.

Thanks for the clarification on the Poetry international events too, I’ll try and update and clarify. On the 1962 visit – he was listed as attending the 1962 writers conference in Edinburgh in John Calders obituary. Is that incorrect? All help appreciated – this isn’t really my territory so I welcome input from better-informed sources.

Great look back at a very interesting past, Mike..I hadn’t realized there was an Iona connection.

You mention Edwin Morgan at one point, and I chanced upon a quote of his in an old notebook the other day, which seems to me speak to us today, and I can only read as a kind of warning of what is to come. It’s from an essay called “The Resources of Scotland”, dated July 8th 1972, so long before the existence of a Scottish Parliament, and can be found in Morgan’s book of collected essays entitled “Crossing The Border”.

The quote reads: “There is not only a very widespread feeling that some sort of Devolution is necessary, but there is also, now … as a result of entry into the Common Market… the first opportunity for hundreds of years of rethinking the whole Constitutional situation…”

To spell it out: Devolution and the EU went together, and were perceived to go together, as far back as 1972…

… whereas Brexit Britain and Holyrood do not…

PS: In terms of America, what Donald Trump is doing by promoting violence and chaos against racial minorities in Democrat controlled cities, and then describing them as “lawless” and “anarchic” and proposing himself as the solution to the same problem has has created, is exactly what Hitler and Mussolini did in 1930’s Germany and 1920’s Italy respectively, using Black Shirts and Brown Shirts…it is precisely the same tactic. America is well on its way to fascism it seems to me, and the best they can come up with is Joe Biden…

Absolutely Douglas – see here:

https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2018/11/04/superbia-ur-fascism-and-britannia/

Thanks Douglas, great quote

How did we end up here, with Trump and Brexit?

We’re heading into very dark times, I fear.

And the only thing they’ve got to offer is Joe Biden?

Anyone who has read anything about Fascism knows that pure Fascism never makes it into power… it has to work with the conservative forces in society to get into power. In the 1930’s, there was a real perceived threat from the Left by the conservative forces in Germany and Italy. They had a reason for embracing Mussolini and Hitler, in their own minds I mean.

What is the reason for Trump today? Where does that hate come from? There is no Left to offer a challenge to the capitalist hegemony.

The only parallel I can see is that, in 1920’s and 30’s Europe, the conservative elites had largely lost the power to mobilize the masses. They couldn’t connect with the new mass politics of the time, whereas Hitler and Mussolini could.

And these days, the traditional mainstream parties can’t connect with the masses either. They’ve lost the power to connect and mobilize, and you can’t help feeling it’s got something to do with the advent of the internet…the social media specifically…

Maybe too, the Great Crash destroyed the dream of never ending progress and each generation being wealthier than the one before… and people are angry about that. It’s obvious to me that we need a progressive force that can reach the masses the same way the reactionary forces are doing, otherwise, we’re doomed…

I see no return likely to the old politics in the near future…

This is a terrific piece work/excavation, well done Mike, or as Marx would have put it: well grubbed, old mole!

I don’t have time to do in-depth reflections on it, but I have always felt that the dialectics (and dialogics) of liberation are much more complex than sometimes suggested. I have always distinguished between liberation and libertarianism, because I think that the freedom to do anything gets bound up with nihilism, which to my mind is a combination of having no values, and sheer destructiveness. I read The Naked Lunch in the 60s and did not like it at all. Full stop. Capitalism very quickly cottoned on to the possibilities of promoting ‘anything goes libertarianism’ to make tons of money, and for capitalism, that saved the day. They called it the consumer culture, and it is still with us, stronger than ever. The potential (and partly real) liberation of the later 40s, 50s and 60s was sabotaged from within by libertarianism which is really capitalism in a progressive guise. ‘All you need is love’ really meant all you need is sex and drugs! The real heroes of the sixties are not the Beatles and the Stones: they are John Macmurray, Emmanuel Mounier, Martin Buber and Paulo Freire. Personalism, not objectifying women’s bodies!

But I do realise the that we were all up tight as hell, back then. Thanks to the worst of Presbyterianism and Catholicism. And folk like Miller and Creeley and Ginsberg and the Beat poets and Lawrence helped to loosen the straight jacket. That’s what I mean by saying that the dialogics of liberation are complex, not simplex.

In haste… well done Mike. This is the real issue you have opened up. Many thanks!

Thanks very much Colin – I quite agree on the limitations of libertarianism and how it has been commodified and usurped, and I didnt really have space to make proper commentary on the actual literary merit of the Beats in this instance.

Fascinating article . As a long-time ” fan ” of Beat Culture I was aware of Ginsburg since I was 16 but had no idea of his travels in Scotland or that he was a disciple – if that’s the right word ? of C Trungpa , or that the aforementioned was the founder of Samye Ling , which I first visited in 1976 , when it was just one house , not the large complex it is now . I can’t say I was ever greatly impressed by AG’s poetry , though Howl was indeed a literary landmark , but his humanity and generosity of spirit , his desire to find and make connections , his advocacy of love and opposition to hatred and war mark him out as an exemplary human being .

Saw him at Liberty Hall, Dublin (home of Irish Trade Unionism) in the late eighties, hurdy gurdy and all. Riveting article, what a story!

Beautiful piece Mike. Great to see MacDiarmid and Ginsberg side by side. Yeats on Swift springs to mind: ‘World besotted traveller, he / Served human liberty.’

Thanks Niall

Thanks for this article Mike – excellent.

As I, and others have pointed out – it’s the June 29, 1973 International Poetry Festival that Ginsberg read at.

Venue was Queens Hall, London. Readers included W.H.Auden, Hugh MacDiarmid, Bangladeshi poet Farida Majid, Basil Bunting and Anthony Howell. Might have been Auden’s last reading in the UK before he died in Vienna that September…. ’tis reported Ginsberg wept all afternoon when he told of Auden’s death.

Also interesting that before Ginsberg’s Scotland trip on June 21 1973 there was also a Poetry International in Rotterdam. Ginsberg and Hugh MacDiarmid were there together. It was recorded: Macdiarmid is on the record reciting Come Away… / Hush, Hush!

See: https://www.discogs.com/Various-Poetry-International-1973/release/4265983

Regarding the 1962 writers conference in Edinburgh organised by John Calder:

Ginberg – no….William Burroughs – yes; MacDiarmid – yes….

Full listing here:

http://www.edinburghworldwritersconference.org/background/