Letter from Sweden

As the rest of Europe went into lockdown, Sweden stood alone in its response to the pandemic. Six months on, Bella commissioning editor Dougald Hine reports from a country that seems remarkably comfortable with its outlier status.

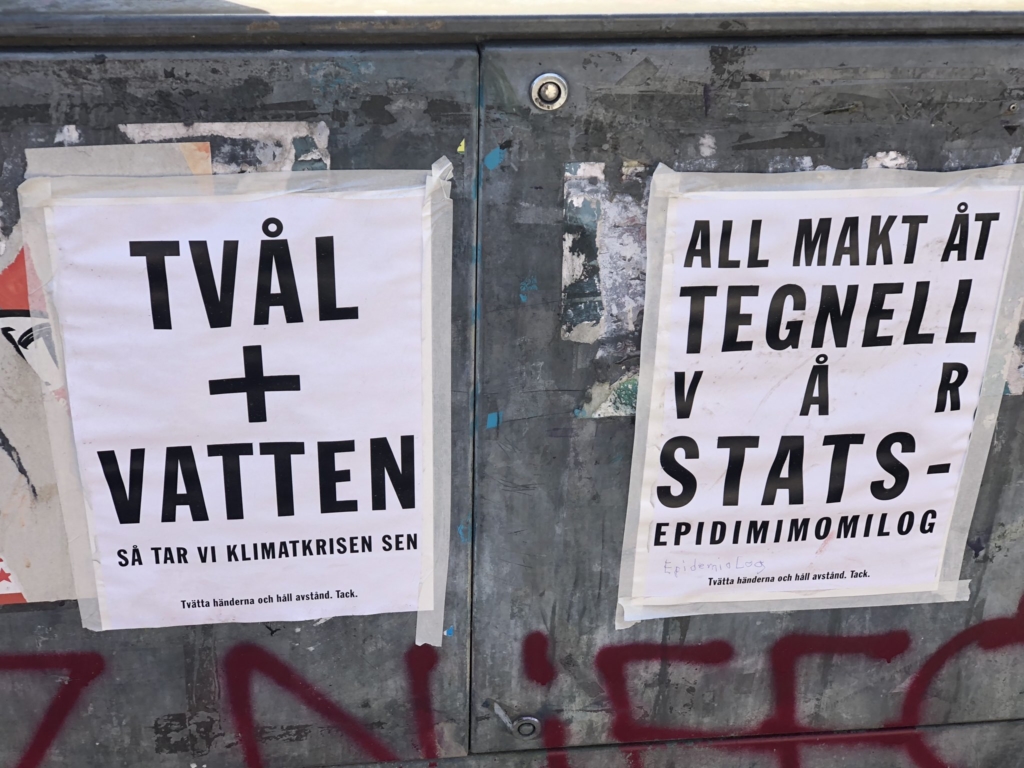

Image: These posters appeared around Gothenburg in late March. The one on the left says ‘Soap + Water, we’ll deal with the climate crisis afterwards.’ The one on the right declares ‘All power to Tegnell – our state epidimimomilogist’. Like many things in Sweden, this is a reference to one of Astrid Lindgren’s children’s books: in this case, The Brothers Lionheart, a fantasy novel in which two brothers travel to the land of Nangijala, where they join the resistance against the tyrant Tengil. This sounds similar to the surname of Anders Tegnell, the epidemiologist who has fronted Sweden’s response to the virus – but the layers of irony involved in turning this (mis)quote into a slogan in support of Tegnell are almost impenetrable. For one thing, the brother at the centre of Lindgren’s story ends up dying of tuberculosis.

* * *

‘It is a myth that life goes on as normal in Sweden,’ Ann Linde insists.

It’s mid-April and the foreign minister is holding a webcast briefing for the international media, arranged in response to the unprecedented level of coverage the country is receiving over its response to the Covid-19 pandemic. ‘Sweden is suffering very gravely,’ Donald Trump declared the week before, and for once his take on events seems in alignment with much of the mainstream reporting.

Appearing alongside Linde is the minister for health and social affairs, Lena Hallengren, who is keen to dispel the impression that Sweden has taken a radically different approach. There are only two major differences in the way we are responding, she says: first, that our schools and kindergartens remain open, and second, that people have not been forced to stay at home. In many other ways, Swedes are changing their behaviour, just as is happening in other countries. The images of crowded café terraces in Stockholm that appeared in newspapers around the world give a misleading impression.

Perhaps it is true that what set Sweden apart from the rest of Europe could be brought down to those two differences, but it branched outwards from there in a hundred ways that have shaped our lives in the course of this strange year. In the first days of April, I was moving house, while many of those I spoke to in other countries were scarcely leaving their homes. The morning after we got in to the new flat, I sent my family in England a photo of my son at a nearby playground. ‘The playgrounds are locked up here,’ my sister wrote back. ‘The virus can survive for 72 hours on metal and plastic surfaces.’

Now we’re six months in, I want to risk some thoughts on the circumstances and mentalities that shaped the response to the pandemic in the two countries that I have had grounds to call home. This is about why Sweden did things differently and how that has worked out so far, but it’s also about the stories we wrap around ourselves when the cold wind of mortality is blowing. And it’s about how we avoid taking the wrong lessons from a crisis like the one we’re living through.

* * *

When you make your home in a country that isn’t where you grew up, there’s always a background sense of living between worlds; but in the eight years since I moved here, nothing had brought this into tension like the early weeks of the pandemic.

In my Facebook feed, one set of friends was sharing charts of exponential curves and agitating for lockdown in the UK, while another set seemed primed to shoot down anyone questioning the line taken by the Swedish authorities. ‘Do you think you know better, because you read some article on the internet?’ This kind of comment became a default response, even when the article in question was written by the editor of the Lancet. Following the public debate in both countries was bewildering: the arguments made by Guardian columnists in London were heard here mainly from the far-right Sweden Democrats, while the policy of the red-green government in Stockholm was suddenly celebrated in the Telegraph and the Spectator. But this wasn’t just about political disorientation. If the articles my British and American friends were sharing had it right, then the country where I lived was headed for disaster; and it was hard to share the gut-level confidence that most of those around me seemed to have in the Swedish system.

For a few days, I carried this as a constant tension, in my thoughts and in my chest. And then a question took shape: what good could come of staging this drama inside myself? It wasn’t going to change the course of events, it just made me more difficult to live with. I had to give it up. To live with one foot in each country, or one half of my head, was a denial of the reality that this is my home now. I was vulnerable, at a bodily level, to the decisions of the Swedish government, and this realisation cut through the half-in, half-out detachment with which I had lived here until this point, bringing me to a new acceptance of what it means to have made a life in this country.

Of course, I was lucky in how deeply integrated I had already become: I’m at home reading Swedish books and newspapers, I’ve spent enough time working in Swedish institutions to acclimatise to some of the cultural differences; and few things will graft you to a country so firmly as raising a child who thinks of it as where he is from.

For others, the choices have been harder. An American friend here told us she had kept her child home from kindergarten for four months. There was a news report the other week of a family in Jonköping whose three children have been taken away by social services because they kept them home from school and didn’t let them leave the apartment. The family’s lawyer explained that they didn’t speak Swedish and had been following the coverage of the pandemic from their home country, but the court upheld the decision to take the children into care.

* * *

For many of us who did not grow up here, what has been striking and alienating is the implacable confidence of Swedish officials, politicians and public voices. A common refrain in the early weeks was that Sweden, with its powerful state agencies, was following an expert-led and evidence-based approach, whereas other countries were rushing into lockdown for political reasons. In this account, the rest of the world was being swept up in pandemic populism, while Sweden soldiered on alone, a last stronghold of rationality. There seemed little acknowledgement of how much remained unknown, that the evidence was limited and required interpretation, or that experts were not united in their conclusions.

When over 2,000 researchers at Swedish universities signed an open letter questioning the government’s approach, a professor who had refused to sign queried the presence of foreign postdocs among the signatories. ‘Whose interests do they think they are serving?’ someone else asked. ‘Not the Swedish people’s.’ It was jarring to hear this tone struck by liberal academics, rather than the usual pedlars of xenophobia: another instance of the through-the-looking-glass landscape of Swedish politics this spring.

On 22nd March, the prime minister Stefan Löfven addressed the Swedish people directly in a rare speech to the nation, broadcast on Sunday night television. As we sat down to watch, I remember there was still an expectation that Sweden was about to follow the path into lockdown taken by other European countries. Perhaps this was what he wanted to talk to us about? Instead, he spoke of the need for everyone to take responsibility, whether by doing the shopping for a neighbour, supporting a local restaurant by buying a takeaway lunch, or avoiding going round to visit your grandmother, but calling her for a chat each day instead.

What stuck with me was his opening description of the situation: ‘The infection is spreading. Lives, health and jobs are under threat.’ By this point, even the Dutch and British governments had found it necessary to clarify that saving lives was a higher priority than preserving the economy, so there was something distinctively Swedish about this rhetorical formula in which ‘lives’ and ‘jobs’ were placed on an equal footing.

In the weeks that followed, international commentators often seemed perplexed by what they took to be Sweden’s prioritisation of its economy. It didn’t fit neatly into the geopolitical narrative of Covid and the state of the world’s democracies. Trump, Bolsonaro and – until he U-turned – Johnson could easily be accounted for as rogue statesmen, happy to sacrifice the old and the weak on the altar of free market economics, but what was a Scandinavian social democrat doing alongside them? Was this a sign of how far Sweden had travelled down the road to neoliberalism? Or evidence for the distinctive understanding of ‘welfare’ that flavours Swedish politics, where the fate of the economy is deeply tied to the state’s ability to provide?

* * *

These are good questions, but I found my mind running in another direction. What I wanted to know was why Sweden seemed so at ease with being the odd one out? At an official level and more widely, Swedes seemed remarkably comfortable with their country finding itself at odds with the rest of the world as to the nature of the situation and the appropriate response.

My suspicion was that this had to do with the role of cultural memory. Just as the politics of Brexit is hard to fathom without accounting for the unfinished histories of Empire and the Second World War, just as Donald Trump is the product of intergenerational traumas already old when his mother left the Isle of Lewis and sailed for New York, so there are deep currents acting within Sweden’s political mindset that pre-date the lived experience of its current generation of politicians.

Somewhere down there is the cultural memory of wartime neutrality, which makes it seem natural to assume that chaos elsewhere in Europe will leave Sweden largely unscathed. Attached to this, I’d guess, is an urge to preserve the economy, so as to replicate the competitive advantage which this country had in the post-war era, when the productive capacity of much of the continent was in ruins.

Closer to the surface, more consciously in play, there’s the memory of the sudden, deep recession of the 1990s: the one major experience of crisis within the living memory of today’s decision-makers. Its legacy may go some way to explain that rhetorical balancing of lives and jobs.

And woven through all of this is the story Sweden likes to tell about its greatness. This goes back to the ‘Great Power Time’ of the 17th century, long-since departed, but still to be experienced in the extraordinary baroque interiors of the palaces and stately homes that grace the landscape of the counties around Stockholm. Furnished in a moment of prosperity, these were preserved for posterity by the decline that followed, when Sweden’s attempts at empire foundered and there was hardly the money to keep up with later fashions. Since the failure of its early modern ambitions left Sweden seemingly free of the moral stains that attached to Europe’s more successful imperial powers, it also helped position the country for its second era of self-proclaimed greatness: the ‘moral great power’ of the high decades of social democracy, ‘the world’s most modern country’, convinced of its own righteousness and its position in the vanguard of history.

In one of the best books written about the political earthquakes of 2016, Anthony Barnett warns of The Lure of Greatness. It might be instructive to compare the toxic invocation of ‘greatness’ in the politics of England’s Brexit and America’s Trump with the strangely parallel role such language plays in Sweden’s story of itself. Swedish exceptionalism is more understated than the American variety, but like the red paint that coats the wooden houses that dot the countryside here, it is made of iron.

* * *

Under ordinary circumstances, I would have written up these thoughts for publication back in March. But during those first weeks, I found I’d lost my appetite for writing. This wasn’t self-censorship; although given the hostility shown to those Swedes who questioned the country’s policy, I understand why other incomers have told me they feel unable to go on the record.

In my case, the reluctance was more general. As the pandemic spread from the edge of our collective field of vision, to eclipse whatever plans or expectations we had been nurturing for 2020, it was met with a rush of content creation. Across the world, or at least across the internet, everyone seemed to have a narrative to throw around this disease, or a way to make it fit with whatever story they had been telling the week before.

The distrust I felt at this came from the guts, rather than the head. The best I could do by way of explanation was this: a virus comes along, and it’s like God walking in the garden in the evening; we snatch up whatever story we were carrying already to wrap ourselves against the sudden sense of nakedness. Better to sit for a while, to let the chill knowledge change us, rather than stitching fig leaves.

When stories are your trade, it’s an odd experience to lose your taste for them. As you can tell, it didn’t last! But for a while, this sense of disgust at the narrative voice was strong enough to stall the writing I’d been doing, including the Notes from Underground series I was working on for Bella.

All I wanted to do was have quiet conversations, where each conversation started with the question, ‘How are you doing?’, and we’d make room for whatever that brought to the table. And if these conversations took place over screens and cameras, that wasn’t so different from how my working days had looked before the virus came along.

Not everyone had the privilege of such quiet conversations, or the quietness that came in between. Even then, it took a choice to still myself, to walk away from the phone that was forever pinging with updates, urgent and important. I did my best to remember to make that choice. To listen in the stillness.

And after ten days in which the aversion to writing had been total, in which all my lust for telling stories had left me, I heard something. It’s too soon to tell the story of this event, a voice said. And it will still be too soon, when it starts to be too late.

So I found myself beginning again – not in the considered voice with which I had been writing a few weeks earlier, but with something more provisional, a public conversation with someone I was just getting to know when all of this began. An opening up of the quiet conversations I was finding helpful.

Through the strange spring that followed, I kept a weekly appointment with the futurist Ed Gillespie, as the two of us puzzled through the stories that were taking shape around the pandemic, and its place within the larger tangle of social, political and ecological crisis. These conversations became a podcast and we called it The Great Humbling, because what had set us talking in the first place was Ed’s enthusiasm for a suggestion I’d been making for years: that if we need a name for the times in which we find ourselves, it might be best to lay aside the academic wrangling over terms like the Anthropocene, the Capitalocene or the Chthulucene, and just call it ‘the Humbling’. The moment in which we get brought down to earth.

* * *

By early summer, Sweden was taking a beating. The New York Times declared it ‘the world’s cautionary tale’, pointing to a death toll many times higher than those of its Nordic neighbours and an economy doing little better. There were countries in Europe which had gone into lockdown and still suffered worse: Italy, Spain, Belgium and the UK. But with infection rates elsewhere falling faster, the last days of May saw Sweden post the highest daily number of Covid deaths of any country in the world.

Against this background, the Guardian ran a piece from the Swedish journalist and TV producer Erik Augustin Palm under the headline, ‘Swedish exceptionalism has been ended by coronavirus’. After a decade in San Francisco and LA, Palm had returned home in March to be near his 71-year-old mother for the duration. Experiencing his own version of the dislocation that went with being attached to two parts of the world with startlingly different reactions to the pandemic, he had written an earlier article for Slate, voicing his horror at Sweden’s complacency, and his peers in the Swedish media had turned on him: ‘I’ve never received so much ad hominem vitriol from colleagues.’

Much of what Palm has to say about ‘Swedish exceptionalism’, ‘a toxic pride’ and ‘a national self-image of moral superiority’ rings true; but the argument of his Guardian piece foundered as he neared a conclusion. With more than 5,200 dead, he wrote, ‘Covid-19 has toppled Swedish exceptionalism’. Even at the moment when the international comparisons looked worst, this claim was wishful thinking. To grasp what I mean, it is necessary to step back and ask why countries around the world brought in such extraordinary measures in the early months of 2020.

The obvious answer, the one that infuses much of the discussion around the pandemic, would be: to save lives. But this doesn’t capture the core motive behind the decisions made by governments. The lockdowns, the travel bans, the ‘shelter-in-place’ warnings and states of emergency introduced around the world – including the restrictions brought in by the Swedish government – were set against a more binary measure than how many of their people would end up dying of Covid-19. What was at stake was the possibility of a systemic collapse of the infrastructure of healthcare. This is what we glimpsed during the worst days in northern Italy, when hospitals came close to breakdown due to the sheer number of mainly elderly patients with acute symptoms.

A systemic failure would lead to far more deaths, not just from Covid-19 but from all the other ways of dying that are prevented or postponed by the activities of hospitals and medical systems in the course of an ordinary week. It would also be an event of the kind that shakes the legitimacy of a regime. It’s not just that no government in a modern state could survive a full-on collapse of its medical system; such an event would call a whole political and economic order into question. This prospect is what brought even Boris Johnson to abandon the ‘herd immunity’ strategy in the second half of March. It’s what caused governments to deliberately bring about the sharpest economic downturn on record. As Jay Springett summed it up for me: ‘They killed the economy to save capitalism.’

Back when all this started, the talk of ‘flattening the curve’ was about avoiding such a scenario. It’s what the viral Medium posts explaining the exponential spread of a virus were about, the ones that gave us the message that Sweden was headed for disaster. So here’s the thing: if the Swedish health system had been overwhelmed, if the stories from hospitals here had been like Bergamo or worse, then Covid-19 might very well have shaken the foundations of Swedish exceptionalism. That would have been a crisis great enough to call a country’s story of itself into question, but it didn’t happen. The field hospital built in Stockholm in the first days of April was dismantled in June, without ever being used. Palm points to the high numbers of deaths, but these don’t amount to the kind of event that can topple a country’s beliefs; they just lead to an endless debate over whether Denmark or Belgium is the more appropriate point of comparison.

* * *

One morning in late August, I catch the train into Stockholm. The journey takes just under an hour and I’m making it for the first time in half a year. The city is quieter than usual, but not apocalyptically so. Masks are rare: not one person in a hundred is wearing one. People go about their business, many of them as usual, some with a definite wariness. I’m conscious of the friction between these different levels of caution, the edge it gives to the way we share urban space. But central Stockholm was always calm and spacious for a capital city, so the effect is hardly overpowering.

House prices are going through the roof, except when it comes to apartments in Stockholm and Gothenburg. There’s talk of a new ‘green wave’, echoing the back-to-the-land trend of the 1970s. I hear stories of employers who are deciding to get rid of their offices and let their staff go on working from home. A friend says everyone she knows who doesn’t work in the health system and who hasn’t been directly affected by the virus has had the most relaxed six months they can remember. Though the university teaching staff I meet don’t sound relaxed, as they head into a new academic year with a mess of face-to-face teaching mixed with Zoom for students who can’t attend.

The news is of rising infection rates in many parts of Europe and the tightening of restrictions, but in Sweden the numbers are still falling. As I write, the latest round of international headlines is focused on the seven-day average of Covid-19 deaths which has fallen to zero. It’s still too soon to draw conclusions, but this doesn’t stop them being drawn.

Depending on who you read, Sweden’s latest deviation from the trends elsewhere means that we’ve reached some form of herd immunity that isn’t fully captured by antibody testing, or that we’re in the calm before the hard winter storm that lies ahead. The chief epidemiologist Anders Tegnell (whose face you see people wearing on T-shirts) repeats a message he’s been giving since the start: the restrictions here are intended to be sustainable for as long as it takes, unlike moving in and out of lockdown, and time will tell whether this strategy was right.

There remain the numbers that are already in: 5,864 deaths at the latest count, almost six times as many per million as in Denmark, more than ten times as many as Norway. To sweep away that difference, any second wave would have to hit our neighbours hard indeed. Some argue the comparison is misleading, that the cultural similarities disguise differences of circumstance which can’t be reduced to lockdown or no lockdown. The timing of the winter half-term holiday for schools in the Stockholm region and the greater tendency for Swedes to fly to the Alps for their skiing meant we imported far more cases in that critical week at the start of March. The lower rate of deaths in recent flu seasons compared to the other Nordic states meant there were just more frail elderly people around in Sweden for this virus to take: according to one analysis, this factor alone could account for as much as half of the total mortality here.

Another kind of analysis will tell you that the strategy Sweden chose has worked just fine for the white middle classes with their suburban villas and summer houses, but left the poorest and the most marginalised groups exposed. This is a country which loves to dress its individualism in a rhetoric of solidarity.

Then, on a point of order, someone will remind you that the Swedish constitution makes no provision for a state of emergency outside of wartime. In which case, there was no scenario in which the government could have imposed the kind of lockdown brought in elsewhere back in March.

I’m not a constitutional lawyer, nor an epidemiologist, though like many of us, I’ve caught myself playing the armchair expert at times this year. It’s one of the defence mechanisms of people with a certain kind of education, to marshal the facts and the theories, as if talking about them confidently enough might make our bodies less vulnerable to infection. We all have our superstitions, I suppose.

One thing I notice, as the months go by, is a slowly widening gap between the people around me here and many of those I speak with in other countries. It’s a gap between our experience of the pandemic and a gap between the state we’re in, after six months of this. When I speak with people elsewhere, I often have a sense of a background buzz of fear or anxiety or exhaustion that belongs to the general environment they are in. It was summed up by a quote that Ed brought when we sat down over Skype the other day to record the first episode of a new season of The Great Humbling. The quote comes from the psychologist Susie Orbach:

The pandemic has been a prolonged assault from outside on our community. The state of uncertainty it has created is new and utterly unfamiliar. Unless you are a refugee who has risked their life to get here, or a survivor of childhood abuse that could not be escaped, there is simply nothing to compare it to.

There are groups in Swedish society for whom this description might fit the experience of the past half year: I think of active older people whose lives have been sharply constrained by following the advice to those over seventy, or of people with existing conditions which make them vulnerable, unable to shield because of the insistence that all children under sixteen attend school unless sick themselves.

Yet looking at Swedish society as a whole, I doubt that Orbach’s words would meet with the kind of recognition they find in the UK and elsewhere. Perhaps it’s that we form a picture of our situation by reading back from what is asked of us: so the more extreme the interruption of life as we knew it, the worse the situation that required this interruption must be. The lightness of the restrictions here has left Sweden less traumatised, it seems to me, and this may have implications that are not fully captured in comparisons of either the death count or the size of the economic contraction. I say this as an observation, not a judgement.

* * *

There’s a line I quoted at the end of our first series, back in June, from the Inuit poet Taqralik Partridge. She asks us to weigh the thought that this pandemic is only the ‘warning shots’ of something bigger: a chain of disruptions coming at all our societies, one way or another, in the times ahead. I picture them sweeping in like storms across the Atlantic in hurricane season. Each storm will make landfall at a different spot. Neither its course nor its behaviour can ever be wholly predictable.

I carried this image around all summer, and then it struck me how it breaks the stories that get told about the pandemic. There are two big stories I hear going around: the one about getting back to normal, and the one where the pandemic is a turning point. Both draw on understandable longings, but they share an assumption that this pandemic is the big event, the great interruption. If that’s not the case, if what we’re living through is just one in a run of gathering crises, then neither of those stories really works.

You don’t have to look far for clues as to what is coming: the orange skies over California, the people making desperate journeys in tiny boats across European waters, the tinderbox of American democracy. The list goes on, and still the reality of the next storm will catch us off-guard. Remember how suddenly and sharply the world pivoted in the weeks when the pandemic made landfall. How quickly measures which seemed unimaginable became everyday.

If these are the warning shots, then there’s no sense in a return to business as usual. It’s business as usual that’s bringing on this chain of crises and the next crisis will be along soon. But nor can we make this the moment when everything changed, the clearcut turning point, on the far side of which we all came to our senses. There is no far side, just the muddy meanwhile where we make life work together as best we can, learning to ride out the weather of history.

There’s one more lesson I draw from this way of thinking, and it’s this: the societies which found themselves best placed to weather this particular storm would be foolish to take that as any kind of vindication. Let’s say we can look back in another half a year and conclude, with a confidence that would be misplaced now, that Sweden got something right in its response to the pandemic. This wouldn’t mean that everyone else should have done what we did here: more likely, it would indicate that ‘social distancing’ describes the way life worked in Sweden all along! When the two metre rule was scrapped here, a Facebook meme asked: ‘Are you going to carry on keeping two metres distance, or go back to five metres like normal?’ This is a big empty country with more one-person households than anywhere else in Europe, and I’d guess that Swedes visit their elderly relatives less often than pretty much anyone else. I still remember in my first year here, a retired Social Democrat politician in her seventies telling me proudly that Sweden’s old people don’t want their families involved in taking care of them in any way; instead, they are taken care of by some of the lowest-paid and most precarious workers in this society, many of them migrants from the Global South.

If Sweden did evade a full-on disaster while avoiding the traumatic effects of lockdown – and obviously that’s open to debate – then it’s down to the way we do things here, for better and for worse. It doesn’t mean the Swedish way would have worked elsewhere, and it doesn’t mean that Sweden will be well-placed to weather the next storm. In some ways, that’s what troubles me most: that we will draw unwarranted conclusions from this whole pandemic, breeding a complacency that only sets us up for a greater fall somewhere not much further down the road. Because if this is a time of humbling, I don’t see that any of our societies are likely to be spared, and there’s certainly a great deal that is dysfunctional or brittle in the way we do things here in Sweden. It would only take a storm blowing from a slightly different direction to show us just how far we have to fall.

* * *

Dougald will be resuming his Notes from Underground series for Bella this autumn. Meanwhile, you can revisit his long read from last September on Sweden’s story of itself and its role in the political imagination of millions of people who have never been there – or listen to the latest episode of The Great Humbling, available through all the usual podcast platforms.

Excellent read !

I remember some of the criticisms of Sweden’s approach way back in the early days of this pandemic . I was inclined to think that they had chosen a risky path but as the writer says , it is perhaps too early , even now , to say which strategy is the best .

What I would say is that , whatever approach a country chooses it must NOT be led by a buffoon like Johnson .

Since this is an infectious respiratory disease, the capacity for its spread and impact on populations is hugely different in different types of urban environments. Population and household structure are also important social factors. Some countries are ‘younger’ than others. Some have multi-generational households, others like Sweden seem to have a large number of single person households.

Hi Dougald,

I’m a Brit/Scot/Swede who has been living here since 1965. I read this with great interest. Initially there was very little hard data on which to base a rational covid response so each country had to guess. In Sweden, as you point out, the public health authorities called the shots, not the politicians. Interestingly the economy was included in the wider sphere of public health. By and large the Swedish approach seems to have worked in Sweden, which is not to say it would necessarily have worked in another country. The shocking thing about the Swedish experience is the severe death rate of the “elderly elder”, i.e. the over-70s. The remainder of the population, apart from a minority suffering from other big health issues that make them vulnerable, have kept healthy or had mild covid-19 experiences. My own experience as a near-octogenarian is that even close to Stockholm, the oldies who have not been in care homes have managed pretty well, although everyone is chafing at the self-isolation. So far I would say that the most important conclusion to date is that the Swedish care of the elderly has to be reformed and big improvements in salaries and training of the health care professionals involved must be introduced now. As to the future, I absolutely agree with you that big shocks are coming. The countries that spend money preparing for this and improving their public health are wise, instead of squandering their wealth on grand gestures such as Brexit and Make America Great Again.

As we both live in the Stockholm area, maybe we could get together and chew the cud on the present and future relationship of Scotland with the Nordic countries.

Thank you for this insightful analysis and perceptions of current life in Sweden.

As a frequent visitor to Norway, I think you hit the nail on the head when you said that it worked because normal life in Sweden was socially distanced anyway. The number of one person households, the spacious and calm capital, the country houses and cottages, the capacity to have a home office and work from home. Life did not change much, in other words. (Except for the clinically vulnerable, who were creamed off.)

Norway has a similar demographic, with large numbers living in the countryside and country general stores being spacious with wide aisles, unlike my local Tesco in Edinburgh where I live in a tenement with 4 HMOs in my stair. (Luckily though, there is at least a large communal garden. Many tenements don’t even have that). There is not the tight urban fabric and density in Sweden of Spain or Italy, where you can sing to your neighbour across a balcony. Or cough. Coming back to Scotland from a country district in Norway at the end of July, where my house is on a one acre site and 20 metres separates me from my neighbours on either side, I was struck by how, even in a comparatively empty country like Scotland, in small towns and in the countryside, Scots live jam-packed together. Driving back from Aberdeen to Edinburgh through Deeside, Banchory and Ballater, even homes in country towns and villages were tiny, cramped and huddled together. Unlike most of Scandinavia. In the UK as a whole, land prices are so high that people live crammed together in shoe boxes and rabbit hutches, meaning that the temptation of the pub is always a powerful lure, yet public places such as cafes and restaurants are similarly constrained in size. Perfect conditions for the rapid spread of infectious disease.

So it looks likes Sweden’s strategy suited Sweden, because of its demography, urban patterns and housing. It’s likely that herd immunity has accumulated meanwhile amongst anybody who wanted to get Covid in Sweden, whilst those who wanted to avoid it could stay safe at home with little change to their comfortable and secluded lifestyles. This is basically what other countries are also trying to achieve, but they have patterns of urban density that make this far more difficult to achieve.

Before the Swedes start crowing about their success, they should reflect on the fact that housing, urban fabric, and households are very different from the rest of Europe.

And as for the rest of us? We need bigger houses for everyone, with more garden space, more space between housing and capacity for a home office. And fewer HMOs.

Thanks for this, MBC. The point about the role of land in all this is strong – and deserves an article in its own right. Not least, the combination of the historic role of landlordism in creating the different public health contexts, with the way that the pandemic itself and the political response plays into the power imbalance between landlords and tenants. Whatever thread we pull on, trying to make sense of the world and how it got this way and why things play out as they do, so often it seems to bring us back to land reform and our situation as landless peasants.

I think this disease will always be with us but will become less dangerous over time as management of infection and medical treatments improve.

There does seem to be something important in the concept of ‘viral load’. I.e., the sheer volume of virus particles that are present in any environment that might infect you if you come into contact with it – young, healthy people can have a serious and even fatal illness if the viral load to which they are exposed is massive, whereas a 100 year old being shielded from the virus but accidentally receiving a ‘glancing blow’ of fewer virus particles, might actually fight it off.

The bad news is that respiratory diseases are on the rise and more corona viruses are in the pipeline. This must affect planning for the future.

The design of mass transport systems

Lesser use of public transport and greater use of private transport

Limiting the need for travel

More home working and design of housing to reflect this

More garden space and physical distance between housing units

Testing of travellers at airports

More people employed in public health and infection prevention

Fewer people employed in tourism and hospitality

Fewer hotels and office buildings – urban space should be prioritised for decent housing and gardens

Thanks Dougald for a thought provoking piece.

Thirty years ago I spent a year as an exchange student in Lund in the south of Sweden. I’m sure things have changed a great deal (I went back about four years ago with my family) – at that time each area or ‘land’ in Sweden had its own student union in the town, outside of these there were few pubs. In the hall of residence I stayed in things were very much formally organised with the seven other people on the ‘corridor’. Compared to Glasgow, looking back it felt like society in Sweden was organised in a series of social bubbles, which once you were in them could be quite enriching. Of course there are pluses and minuses to the way all societies organise themselves. Maybe this has factored into the Swedish approach to the pandemic?

For me one pressing thing common to Scotland and Sweden is that we need to reappraise how we provide care to the elderly.

In a more general response to the discussion about planning – we do all need high quality green spaces near at hand for physical and mental health.

The fifteen minute neighbourhood promoting active travel and healthy living included in the latest ‘Programme for Government’ is an attractive proposition and must be part of measures to address this and wider issues we face.

(It is good also to see ‘Place Making’ recognised by the new agency ‘Public Health Scotland’)

Hi Dougald,

Thanks for such a thoughtful long form article. I honestly wouldn’t have much to add as a resident in Sweden. I see your point regarding World War 2, and Sweden’s “neutrality”. I’ve seen that comparison before, too, perhaps it could do with an even deeper dive and understanding.

I’m still living in Stockholm, I made a seamless (almost!) transition to working from home mid-March and didn’t return to the office until early August. One of the things that really marks Stockholm out from other cities that I’ve lived in (Glasgow and London) is the sheer number of forests and parks that pepper the city spread, and they’re massive areas! And this is my point, social distancing is ably supported by vast green spaces, parks and nature reserves. On a normal weekend, these places are quite quiet, but I noted a significant increase in numbers around the time all of this started.

Moving forward, far in to the future, and I’m thinking about Scotland here, investment needs to be placed in WiFi (Corbyn, anyone?) and good quality housing adjacent to such areas so capital city populations can be allowed to plateau in population density or even decrease. Of course, Lesley Riddoch has investigated and documented similar themes.

It’s heartbreaking what happened in the care homes in Stockholm, privatisation of care homes is more common in Sweden than, say Norway. The political ramifications for the Christian Democrats will be interesting when the investigation into what happened there is published. My understanding is that sector is under their chain of command in Stockholms län. Finally, having moved here, working where I’ve worked and living where I’ve lived, I have become deeply sceptical of what Sweden’s definition of “Social Democracy” has become. Sweden is on a very dangerous path at the moment, racism is rife — like, literally, on your TV screens every day via TV advertisements, programmes and populist politicians — furthermore the way it kowtows to the U.S. leaves me deeply at unease.

Sorry for this rambling comment, these are just a few things that sprung to mind. I’m slowly arriving at the realisation that when Olof Palme died, so much more died with him.

A very good article.

Congratulations for writing an opinionated hitpiece that scews facts filled with unsubstansiated claims of nationalism. The habit of using your own unbacked opinions as facts is a travesty. Atleast you can admit you are clueless yourself in the article and are a pretend armchair “expert”. Worst article I read in a long time, try sticking to facts and not weird musings about national history and how it explains this and the other. Its just awkward and stumbling. Besides. Lives, health, economy. In that order. Its interesting to see that you dont believe economy has anything to do with lives or health. Very naive indeed.

Hi Rob,

Thanks for taking the time to leave a comment.

Leaving aside your stylistic criticisms, perhaps you’d like to be a bit more specific:

(1) Which facts are you saying that I’ve skewed?

(2) Where are these unsubstantiated claims of nationalism?

(3) Where do I suggest that the economy has nothing to do with lives and health?

Like Lena Nyman on the streets of Stockholm, I am curious!

Dougald

Stefan never said in his statement that lives and jobs were on equal footing, yet you claim he did. The meaning behind was that lives, health and jobs are under threat. The meaning behind the statement was an earlier made by Tegnell that said that a lock down and loss of jobs would lead to increased mental health issues and domestic disputes, and also pointed out the generation of young people who grow up under though economic circumstances will be hit mentally in a long lasting way. Your framing of the economy is instead one filled with leading questions to lead to a conclusion that the Swedes are happy to sacrifice the weak and the elderly. Tegnell made it clear: Sweden wanted to save lives and flatten the curve, and decades of decline in elderly care reaped its harvest.

As for the ”2000 Swedish researchers”, that arguments been long debunked. Out of the 6 main authors of this document 0 worked in public health. A majority of signatories were students, and the majority of those that were ‘experts’ were experts in other fields. There were also a handful of foreign ‘experts’ as cosignatories. They wanted Sweden to follow WHO recommendations and falsely claimed that Sweden are having a herd immunity model, something Swedish health authorities stated many times we’re not. As for ‘not following WHO’, WHO has called Sweden a model case. To criticize this document is hardly xenophobic as you claim, its just common sense. I strongly suggest you read this article: https://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12992-020-00588-x which will hopefully have you more up to date. I strongly advice you to research before writing things, else you are just riding a populist wave.

Your ‘cultural memory’ rant is truly rancid. You mention 17th century nationalism. Wartime neutrality. You make an unsubstantiated claim of Swedes being ‘convinced of its own righteousness’. And then you call your false understanding of this ‘cultural memory’ as toxic, claiming ‘invocation of greatness’. This is trash ‘journalism’, though it should be called fiction. How can you mention Swedish cultural memory without mentioning ‘Folkhemmet’ or ‘The people’s home’ is beyond me. It’s pure insanity to not include it if you want to have a serious discussion. Nor have you included ‘Jantelagen’.

Rather than invoking greatness, paraphrasing Tegnell: ”We are just trying to flatten the curve like everyone else”. What the health authorities also said was that Sweden are prepared and won’t be overwhelmed. And instead of claiming that we got it right, Tegnell pointed out that he doesn’t know for certain and that each country got their own unique culture they need to take in to account. Claims of invoking greatness is the antithesis of the Swedish law of Jante.

As for comparisons to other counties virus response, you hardly do that complex debate any justice with a throwaway sentence to further your negative narrative. Safe to say is that media are having a battle that the Swedish health branch wants to avoid since its not constructive at face level and its not a competition.

Your narrative throughout the article is painting Sweden as arrogant and trying to claim vindication, you are building up a mighty straw-man you want to pierce with your pen. Your article is a hit piece and its not constructive and it skews facts and interweaves facts with opinions. The goal of this article seems to me to be to counteract against others taking the Swedish way of handling the pandemic by scare tactics and populism. And here is the great irony of the article. ”…that’s what troubles me the most: that we will draw unwarranted conclusions from this whole pandemic…”. Then don’t draw unwarranted conclusions yourself eh?

No, Rob, I’m sorry, this won’t do. It’s clear that you are angered by some of what I wrote, but to characterise the piece as a ‘hit job’ is a travesty. As you’ll see from the reactions of other commenters here, it bears no resemblance to how the piece comes across to a reasonable reader.

What I wrote was a sincere and informed attempt to make sense of the experience of living through the past six months as an immigrant to Sweden from the UK. Nowhere in the piece do I direct the reader to ‘a conclusion that the Swedes are happy to sacrifice the weak and the elderly’.

Rather, I emphasise that ‘It’s still too soon to draw conclusions’ and that it may be that ‘we can look back in another half year and conclude, with a confidence that would be misplaced now, that Sweden got something right in its approach to the pandemic’. I emphasise that there are good reasons to question the simple comparisons to other Nordic countries that are typically made in articles criticising the Swedish response. And my final observation in reviewing where we stand, six months after other Western countries went into lockdown is cautiously positive about the wider consequences of the Swedish response:

‘The lightness of the restrictions here has left Sweden less traumatised, it seems to me, and this may have implications that are not fully captured in comparisons of either the death count or the size of the economic contraction.’

Given the subject matter, even an article as lengthy as this one must pass briefly over material that deserves to be explored in greater depth. You seem particularly exercised over my drawing attention to the resonance between the ‘stormaktstid’ of the 17th century and Sweden’s 20th century self-image as a ‘moralisk stormakt’. Of course the latter of these is intimately tied up with the history of social democracy, including ‘folkhemmet’. But I should point out that my previous article on Sweden for this site discussed the complex history of ‘folkhemmet’ in some detail:

https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2019/09/13/whats-happening-in-sweden/

It’s true that I don’t invoke Axel Sandemose’s famous ‘Jantelagen’ in either piece; though to be fair, while Swedes have often recognised an aspect of their society reflected in the laws of his fictional town of Jante, Sandemose himself was a Dane writing in Norway.

More to the point, when I discuss the role of the rhetoric of ‘greatness’ in these two key concepts through which Swedes understand their history and their country’s role in the world, I explicitly draw the parallel to ‘Great’ Britain, where I grew up. So again, this isn’t an outsider doing a hit job against Sweden, this is someone engaging in critical reflection about the two countries in which he has a deep personal stake.

In the case of the open letter: I discuss this briefly in the context of the larger piece, so there isn’t room to go into a discussion about the credentials of those involved, nor the strengths and weaknesses of the argument made in the letter. Nor do they affect the point I was making about the responses that I quoted. Anyone familiar with the history of xenophobia in Europe will tell you that the singling out of contributors as questionable on the basis that they are ‘utländsk’ and the assertion that whatever interests they are serving are not the interests of ‘svenska folket’ are familiar tropes.

As for Löfven’s rhetoric in his tal till nationen – does anyone think that ‘Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ or ‘Liberté, egalité, fraternité’ are lists in descending order of priority? This type of rhetorical formula is generally understood to signify three things that are being put on an equal footing, but I’m happy to accept that the line can be read in the way you choose to read it. All that shows us is that Löfven’s rhetoric was ambiguous, to say the least, at a stage when Dutch and British political leaders were going out of their way to clarify that they viewed the cost in lives as a higher priority than the economic cost.

I actually accept much of what you say about the complexity of the relationship between public health and the economy – and you won’t find anything in what I wrote that dismisses this. It’s worth noting, of course, that those arguing the case against the Swedish approach will point to evidence in favour of harder lockdown policies on the basis that they cause less economic damage in the long-term than keeping your society open. (The comparison between different American cities during the influenza pandemic of 1919 is the usual reference point.) Again, this is not the argument I make in the article; rather I suggest that it is too soon to draw conclusions.

I’m sure you can find more things to argue about within what I wrote, though I doubt that anyone will gain from us extending this exchange much further. But let me finish by directing you to the actual argument around which my piece is built:

1. The Swedish response to the pandemic has been markedly different to that in other countries. (The personal example from early April which I use in the opening section is one illustration of this, but there are many others available.)

2. The extent to which Swedes appear at ease with their country taking a different path to others – and quick to argue that everyone else is wrong – is distinctive. Many of us who came here from elsewhere find it hard to match this level of confidence and hard to imagine the societies we came from showing a similar level of confidence under similar circumstances.

I take this as the starting point for an enquiry into what aspects of Sweden’s history may have contributed to this confidence. You object to this. But your aggressive mischaracterisation of what I wrote doesn’t do much to dispel the sense of Sweden as a country ‘convinced of its own righteousness’.

Ridiculous