At Least We Won’t Be Bored

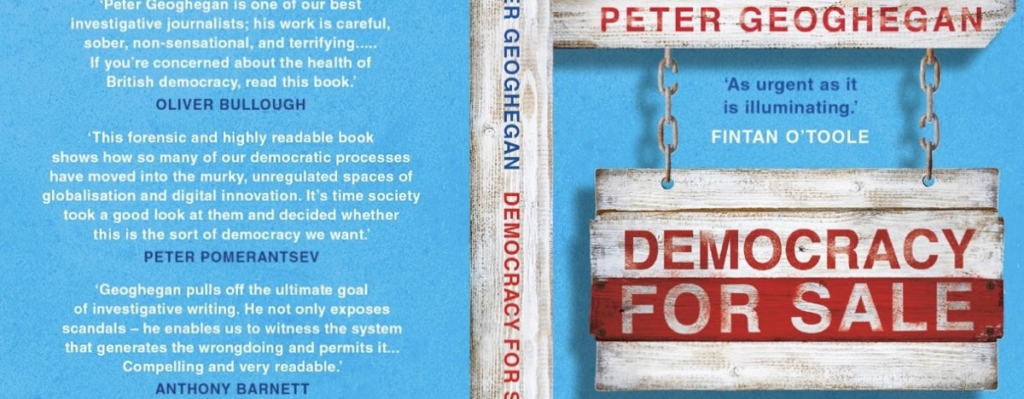

Review of Democracy for Sale: Dark Money and Dirty Politics, by Peter Geoghegan, Head of Zeus. Democracy for Sale has been our Book of the Month, see also our interview with Peter here.

I suspect I’m not alone in never having heard of Richard Cook. In Democracy for Sale we learn that the Clarkston based businessman channelled unprecedented sums of money to the DUP in the weeks leading up to Brexit. The book also delves into the labyrinthine multi-million dollar export deals that Cook’s recycling company became involved in. The firm seems to have been in the habit of shipping a range of questionable cargoes to India, Malaysia, South Korea and Ukraine. In a text filled with incongruous locales and characters, the twists and turns of these particular dealings read, ‘like excerpts from an airport thriller.’

Although a digression from the meat of the book, this tale points to a wider problem. If a trade as mundane as recycling can become embroiled in global intrigue; is it really any wonder that that the higher-stakes realm of politics seems increasingly beyond our grasp?

Democracy for Sale is a page turner: a compendium of thrilling, grotesque and surreal sub-plots that together constitute an extensive assessment a sustained an authoritarian nationalist backlash. All manner of networks and connections are unpackaged at a bewildering pace. This is a great testament to the investigative journalist’s zeal. But it would be naïve to consider the range of scoops compiled by Geoghegan and his colleagues here as akin to the genre’s classic triumphs of the last century. Indeed, by the end of the book, you yearn for the relative innocence of an era in which elites at least felt obliged to cover up their bad behaviour.

Of course, bad characters, acting with impunity, make for good stories. The worst, and their passionate intensities, know how to blend politics and entertainment as celebrity self-image. However, a coherent response must be both systematic and structural: and thus destined to only be of interest to the woke/liberal/normie establishment.

This brings us to a conundrum that the traditional frames of politics and journalism struggle to contain. Trump’s global saturation and reach is more akin to that achieved by Elvis than the state-centric project of, say, Mussolini (brand reach was of course Trump’s original intent in running for office). It is unsurprising then that the new breed of ‘strongmen’ are invariably so skittish, bitchy and infantile – time and again this book reminds us that it is the dynamic of attention seeking that has evicted politics from the agora and dumped it in a murky and seedy alleyway. Yet, a bit like the transformation of Bedford Falls into Pottersville in It’s a Wonderful Life, the dark inversion of upstanding civic virtue can promise a lot more fun.

Whether it’s the legacy of HIGNFY, the ‘stand-up comedian’ founder of pseudo-militia Proud Boys, or the glee with which a man as powerful as Aaron Banks courts notoriety, a significant part of the dynamic that has disrupted democratic custom is the desire to be in on the joke: to be amongst the laughing, rather than the laughed at. For want of anything more substantive, the media-incubated rulers we’ve ended up with only really promise us one thing – at least we won’t be bored. Those of us who want to resist their policies need to get better at understanding how tempting this offer can be, whilst also admitting that our own indignation fuels their communicative power. Why bother with the all the slow and difficult work of politics: empathy, consensus building, self-education, compromise, when you can simply tune in to whatever ‘shitshow’ happens to be on air? Writing in The New Republic, Osita Nwanevu points out: ‘Support for Donald Trump and the Republican Party is as much, if not more, a cultural practice as it is an abstract political stance or a reflection of clear policy preferences.’ The rites of this cultural practice are all about gaming the public sphere: shitting in all the places where dialogue in good faith might occur, mining outrage, refusing, above all, to accept that any concern alien to your own experience deserves to be taken seriously.

Geoghegan doesn’t shy away from pointing to the origins of the unfolding erosion of trust that has created this dark politics of spectacle. After neoliberalism gorged on the innards of public institutions, and post-war paternalism collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions, the logic that certain holy cows in society should not be available to the highest bidder has inevitably worn thin. In unpicking a vast catalogue of bad behaviour, Democracy for Sale invariably returns to a trio of problems now haunting public life: big-data monopolies, offshore finance, and a reluctance to regulate. With these vital ingredients still in play, it is hard to read this book and not conclude that the devotees of self-interest may indeed finally roll back the last bastions of the state. Global-Singapore-Free-Port Britain here we come.

Because this is a long process (the Institute of Economic Affairs was founded in 1955) it’s difficult to fix a point at which democracy was cleaner and more enlightened. Looked at another way: if there was a Trente Glorieuses of better politicking between 1945 – 1979, this is surely an aberration in the grand scheme of things. Graft and corruption seem inevitable in polities defined by enormous inequalities. We are, as the author concludes, in a new gilded age with more opaque robber barons: then as now, the exaltation of private wealth is destined to produce an ever more impoverished public life. When the pinnacle of public service demands a six figure income: as made so clear by Jack Straw and Malcolm Rifkind (and for that matter, any head of a Russell Group university) there is only one gut-level conclusion for the rest of the populace – if everyone’s in it for the money, who can’t be bought?

Some of the problems dissected in Democracy for Sale are also less novel than we might like to imagine. George W. Bush, now frequently wheeled out as an exemplar of moderate bipartisanship, oversaw an administration that lavished budgets on ‘message force multipliers’: a cast of nominally independent paid-for talking heads who pushed pro-war opinions across broadcast networks. As Jodi Dean points out, strategies to flood communication channels in this way are better likened to spam than propaganda. They presaged the current torrential slurry of politics as shitposting that this book, so eloquently and hygienically, delves into.

While the author’s political self was birthed under the lodestar of possibility achieved by the letter and spirit of the Good Friday Agreement, for those of us who came on the scene only a few years later, it was another document, trumpeting claims about 45 minutes, that set the tone. Before I was old enough to vote, mainstream politics had been dominated by a debate on the gravest matters of state that was deliberately disinformed. Those at the apex of the system didn’t require webs of dark money or the wild-west of digital disruption to orchestrate that particular coup. They now enjoy magnificent careers as elder-statesmen and lifestyle coaches. At the risk of straining a metaphor to death: if the lights are going out for democracy due to authoritarian nationalism, ‘moderate’ politicians who thought they could control the dimmer switch for their own ends have just as much to answer for. Here we arrive at an awkward truth. The success of this book in charting the shocks to established political systems may allow for the more presentable charlatans of yesteryear to point to the rise of malign Kremlin interreference in democratic contests. But they will, presumably, gloss over passages which reference the catalogue of past disruption, often fuelled by dark money, that has long been pivotal to the conduct of our foreign policy. Perhaps the practice of protecting democracy at home by undermining it abroad was always destined to come home to roost.

The fierce and meticulous intellect at work in Democracy for Sale has sent up a flare, but a distress signal is not enough. Increasingly, tiny numbers of journalists, funded largely by philanthropy, end up providing the only alternative to the cloying secrecy and non-disclosure that defines contemporary politics. Might a generalised, reforming, sense of shame emerge from this work? It’s possible, and a range of practical fixes are offered here. But when we consider the example of the paltry resources of the UK Electoral Commission (with a staff of only 140 compared to Facebook’s 3,000 in London alone) and the inconsequential fines it doles out, we have to first admit that these are yet another example of malnourished Thatcherite offspring. When so many in power believe that the market is the ultimate democratic system, we cannot be surprised that so much of value has been left to wither. As it happens, the original ‘gilded’ tag referred to the shallow facade of wealth distracting from an era of political upheaval. Scratch away the bling and you find a society in turmoil.

Meanwhile, the chaos of the new media technologies continues to merge with the worst of the old. Geoghegan points out the strikingly similar content that many of the plethora of new ultra-partisan platforms news websites share with outlets such as the Mail and the Express: part of a ‘raging digital wildfire’ of conspiracy, disinformation and partisanship. In contrast, Democracy for Sale is an all too rare exemplar of the old fashioned notion that journalism as public service ought to be about wading into a sewer and bringing something back to the surface. Left to the online world of clicks and metrics – time and again journalists will be tempted to go native in the netherworld in the drive to compete for attention.

Unsurprisingly, Clarkston cowboy Richard Cook responded to details of his company’s misdemeanours as ‘just fake news’. In a political sphere where the implausible feels constant, deniability is a given, and the matter of your money and what you choose to do with it is deeply personal and private. Such assumpetions have brought us to a point at which, as Geoghegan concludes, ‘the rules of the democratic game are not fit for purpose.’ However, with electoral breakdown looming in America next month there is also the more immediate problem of the range of current players: cosseted narcissists elevated off the back of long careers as rule breakers and fixers. At least they’re not boring.

There’s a huge amount in this review, let alone in the book itself.

“The rites of this cultural practice are all about gaming the public sphere: shitting in all the places where dialogue in good faith might occur, mining outrage, refusing, above all, to accept that any concern alien to your own experience deserves to be taken seriously.”

This neoliberal glorification of selfishness seems like

– such a sugar rush, such an addicts hit, such an addiction to endless outrage, to “I’m right, you’re wrong”

– such a click click click of empty soulless grabbing to try to try to fill a void that is utterly bored and utterly boring.

There is a very different way of doing politics, but it starts from conversations, from being honest, being difficult, being willling to listen, recognising our part, disentangling where we are repeating the same old lies from where we are doing something new. That goes as much for intimate relationships as for making a new politics localy, nationally and globally. Its tender, its honest, it hurts. Its us in recovery, starting with the recognition that we are addicted to a system that is utterly awry, and that we are not that system, and that detoxifying is very hard but utterly liberating.

“When so many in power believe that the market is the ultimate democratic system, we cannot be surprised that so much of value has been left to wither. ” That says it all. Thankyou Christopher for an insightful review of a must read book.

If you publish this can you publish this version with the paragraphs?

1: We have f*cked up the environment so badly that we don’t have the technology or even the understanding to put right the damage we have done. The environment is what keeps us alive.

2 : We are spending more of our money on “defence” than anything else, which translated from politics-speak means murdering millions of our fellow human beings to satisfy our deranged overlords and their politician sock puppets.

3: We have no more real freedom than medieval serfs, the difference being that we are slaves to money which gives the illusion of freedom. The freedom to choose which billionaire owned newspaper you can be brainwashed by and which car you buy is equivalent to offering a medieval serf the choice of which horse he can use to plough his lord’s field with. “Look how free you are, you can use the brown horse, the black one or if you’re really good the piebald one, look how pretty it is”

4: “Ordinary” people are forced under threat of imprisonment to surrender a substantial portion of their income to the state but they have no real input as to how this money is spent. The 1% can get away with paying token amounts of tax because the laws which govern this have been written by and voted on by their bought and paid for politicians.

5: The only potential threat to any of this in the UK was neutralised by Starmer becoming head of the Labour Party. The choice is now between a hardcore fascist dictatorship and a right wing Labour party. The possibility of a mildly centre left Labour party led by Corbyn was greeted by a hysterical campaign of vilification, abuse and lies by the BBC, the billionaire press and the Blairites in the labour Party. Which brings us to

6: The majority of voters in the UK have been subjected to one of the most sophisticated mind control programs ever to be unleashed on the human race. The Nazis and Communist regimes would have sold their souls to have had anything as effective as this to control their citizens. Collectively we are not only brainwashed but we are incapable of recognising that we are brainwashed. “I am free to read the Guardian, it has that lovely George Monbiot in it, I cannot possibly be brainwashed”

So if you add what the article is about to all this what I am seeing is a dying civilisation. It is like a modern equivalent of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, but whereas that took about 100 years to fall apart, things move a lot faster now. The whole setup could collapse in weeks. Yes it would be a shock and many would be traumatised but we could survive and begin to do things differently.

Is the market the ultimate democratic system ? F**k naw.

Thanks for whetting my appetite to read this bok.

Stimulating review. Political support as cultural practice resonating in a west of scotland context…

The ultimate democratic system is a free market: an unregulated interaction of equal voters, with free competition among parties for our votes.

The problem is that the agora is not free; our interaction as citizens and competition among power-seekers are distorted by interference and regulation by the established power-holders, in ways which Habermas and other critical theorists have, in pursuit of their philosophical mission, investigated and documented.

Our task, as democrats, is to resist as far and as often as we can such interference and regulation.

@Anndrais mac Chaluim, you appear to be confused. One dollar, one vote is not democracy. Even very simple models show that tiny variabilities lead to significant inequalities over time (the Matthew Effect, or rich getting richer) which has no relationship to any democratic values. In other words, monopolies are the mathematically-predicted outcomes of free markets.

Anyway, there is no logical reason why a market has to be in touch with reality at all. Panic, fads, crazes, herding, gold-rushing, greater fool thinking, cons and swindles, pipe dreams, circularity, micro-focus (acceleration of short-termism), all kinds of really stupid, vicious and harmful behaviours are likely, and indeed automateable at high speeds. That’s probably why actual companies have planning-oriented superstructures looking years ahead instead of letting the market decide their actions. Market failures occur all the time. That’s why states have had to coordinate world health responses. Or you get market successes like the USAmerican opioid crisis which are social disasters.

In nature, regulation of systems is required. Free market? In your dreams.

Don’t confuse democratic inequality with financial inequality. Rich or poor, in a free democracy we each have only one vote and each vote carries equal weight.

The trouble is that our democracy is not free; economic power can distort our decision-making through the exercise of undue influence. The trick is to constitute our polities in such ways as to check and balance the influence that economic power can have in our decision-making processes. The most effective way to do this is to disperse our decision-making throughout society rather than concentrate it centrally in institutions where it can be ‘captured’ by political parties and other powerful corporate interests.

You say that ‘there is no logical reason why a market has to be in touch with reality at all’. But reality is a market; as far as we can know it, ‘reality’ is just the sum of our intersubjective transactions, and a ‘market’ is the locus of those transactions.

@Anndrais mac Chaluim, would you care to sell me your votes in the upcoming Scottish Parliamentary election? What is your going rate? Perhaps we can come to some kind of deal?

I didn’t know you were standing for election in my constituency or region. Basically, that’s what an election to any representative assembly is: a lending of votes for the life of a parliament.

But if you were standing for election here, I’d have to hear how you would use it before I could even consider lending it to you.

@Anndrais mac Chaluim, did I say I was standing? I may just want to vote multiple times. What’s wrong with that? Sell me your vote. It’s a market, right? Name your price. But make it competitive, it’s a free market.

I couldn’t do that! I’m a democrat! If I sold you my vote, I’d be conniving with you in the use of your economic power to distort the market by voting multiple times. That’s precisely the sort of thing I suggested we democrats need to guard against.