Craigmillar Now – F UK* 2022, WTF?

The launch this week of a major new grassroots arts initiative in Edinburgh comes at a very interesting moment. Craigmillar Now has announced a programme of local-based international arts that aims to rekindle the spirit of the old Craigmillar Festival Society. This has been brought to fruition as a labour of love by people living locally.

*

Entirely separately to this, the event once dubbed the ‘Festival of Brexit’ last week announced a shortlist of teams bidding to take part in the high profile multi-million pound initiative in 2022. With the event now branded Festival UK* 2022, teams feature several major institutions from Scotland. The announcement comes at a time when theatres and music venues are closed due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. With many freelance workers struggling to survive, Festival UK* 2022 has been criticised by some, with questions asked over whether it should go ahead at all.

*

Craigmillar Now and Then

*

Away from all that, Craigmillar Now has begun operations in the former church that was previously the home of Craigmillar Community Arts. Drawing much of its inspiration from Craigmillar Festival Society, the organisation founded in 1962 by the late Helen Crummy and other local mothers after seeking some kind of arts provision for their children, Craigmillar Now aims to provide a year-round artistic programme as well as hosting an archive of its forebears.

*

Already announced is a six-month residency and exhibition by Craigmillar based Syrian artist, Nihad Al Turk, who will develop a new body of work set to be shown in Summer 2021. Al Turk’s work has been seen all over the world, from Damascus to Venice to New York, as well as at the 2003 Latakia Biennale, where he was awarded the Golden Prize.

*

Alongside Al Turk’s work, artist Shauna McMullen will be leading the creation of a new community artwork celebrating the women of Craigmillar. This is designed to replace a now missing Women of Achievement plaque dedicated to Crummy.

*

Craigmillar Now will also be developing a local archive of vital historical material about the area. This will see a team of trained volunteers collecting and preserving the Craigmillar Festival Society archives, featuring documentation of the organisation’s 40-year history up until its closure in 2002.

*

In keeping with this emphasis on living history being passed down through generations, a series of community mapping walks will be led by local 5-11-year-olds. These will be run in collaboration with The Venchie, the Niddrie based children’s activity centre run on the site of what is believed to be Scotland’s first adventure playground, which is currently under threat of closure.

*

*

With other major events set to be announced in 2021, Craigmillar Now has already made quite an opening statement. Despite this, those behind the new initiative are more than aware of the tough act they have to follow. Craigmillar Festival Society, after all, was a boundary-pushing organisation that revitalised a marginalised area of Edinburgh that suffered institutional neglect and a welter of social problems that came in the wake of ill thought out planning decisions.

*

Despite this, during the 1970s and 1980s, CFS and the work it enabled was championed and supported by forward thinking individuals within a well-resourced local authority. The influence of CFS saw it used as a model for community arts around the world.

*

The full background to Craigmillar Festival Society can be found in Crummy’s memoir, Let the People Sing! published in 1992. A short history of CFS appeared in 2017 in Rachael Cloughton’s essay, Dangerous Mothers. This formed part of Dangerous Women, a project initiated by the University of Edinburgh’s Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities.

*

*

Since then, as newly appointed Project Manager, Cloughton has become one of the driving forces behind Craigmillar Now. With support from City of Edinburgh Council and others, Cloughton has worked alongside community councillor Maureen Child, artist Andrew Crummy, who is also Helen Crummy’s son, veteran Craigmillar activist Johnni Stanton and others. Support has come too from Dr Sophia Marriage of Scottish Episcopal Church, owners of the building. With such a strong team in place, Craigmillar Now looks set to pick up from where CFS left off to create a brand new future for Craigmillar.

*

What the Actual…?

*

Meanwhile, just as Craigmillar Now introduces itself to the world, the event now known as Festival UK* 2022 last week announced a 30 team shortlist of teams from Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland bidding to take part in the £120 million backed festival. Selected from 299 entrants, each team will be given £100,000 to hone their ideas during a period of research and development. From this, 10 teams will be selected to create a new work for Festival UK* 2022. This was greeted with criticism by some, with the grassroots Migrants in Culture group calling for the event to be scrapped entirely.

*

Festival UK* 2022 was originally known as The Festival of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and was first announced under Theresa May’s Westminster premiership in 2018. This is a period in history which in light of everything since, now looks rather quaint.

*

Back then, May’s proposed shindig was described by Downing Street as a ‘nationwide festival in celebration of the creativity and innovation of the United Kingdom’. The festival was also described as ‘a unique event’ with echoes of the 1851 Great Exhibition and the 1951 Festival of Britain. Unofficially, the 2022 event was derided as a Festival of Brexit. Perhaps with good reason.

**

“Just as millions of Britons celebrated their nation’s great achievements in 1951,” said May, “we want to showcase what makes our country great today”. May also declared that The Festival of Great Britain and Northern Ireland would strengthen what she called “our precious union”, conjuring up nightmare images of the last night of the Proms on an eternal brain mushing loop.

*

Both the world and the prospects for May’s precious union have changed significantly since then. Brexit has shambled on, overshadowed only by the seemingly unforeseen disaster of Covid-19. Somewhere along the way, the triumphalism of The Festival of Great Britain and Northern Ireland morphed into the far buzzier sounding Festival UK* 2022.

*

With any mention of Brexit excised from its publicity material, Festival UK* 2022’s website outlines its aim of presenting ‘ten open, original, optimistic, large-scale and extraordinary acts of public engagement that will showcase the UK’s creativity and innovation to the world.’

*

Festival UK* 2022’s mission statement goes on to say how ‘Bringing people together in astounding ways, the festival will platform the full range of our creative imaginations by combining Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics.’

*

Such a fizzily upbeat rebrand comes with its own problems, however shallow. As any terminal adolescent can’t fail to notice, Festival UK* 2022 rather wonderfully abbreviates as F UK* 2022. With its knowingly placed asterisk embracing the spotlight like a runaway emoji doing a turn, such a headline grabbing banner is just a consonant away from potty-mouthed opprobrium.

*

Then again, perhaps such a guffaw-inducing acronym was deliberate. Perhaps its wording is a symbolic in-gag on a par with the apparent potential for subversion from within by those taking part. And perhaps that’s the reason the louche looking asterisk seems to be winking at us, letting us in on a joke that might otherwise be lost in translation. Which is why, in the interests of both shorthand and cheap laughs, this article will henceforth exclusively refer to the latest incarnation of Theresa May’s bastard offspring as F UK* 2022.

*

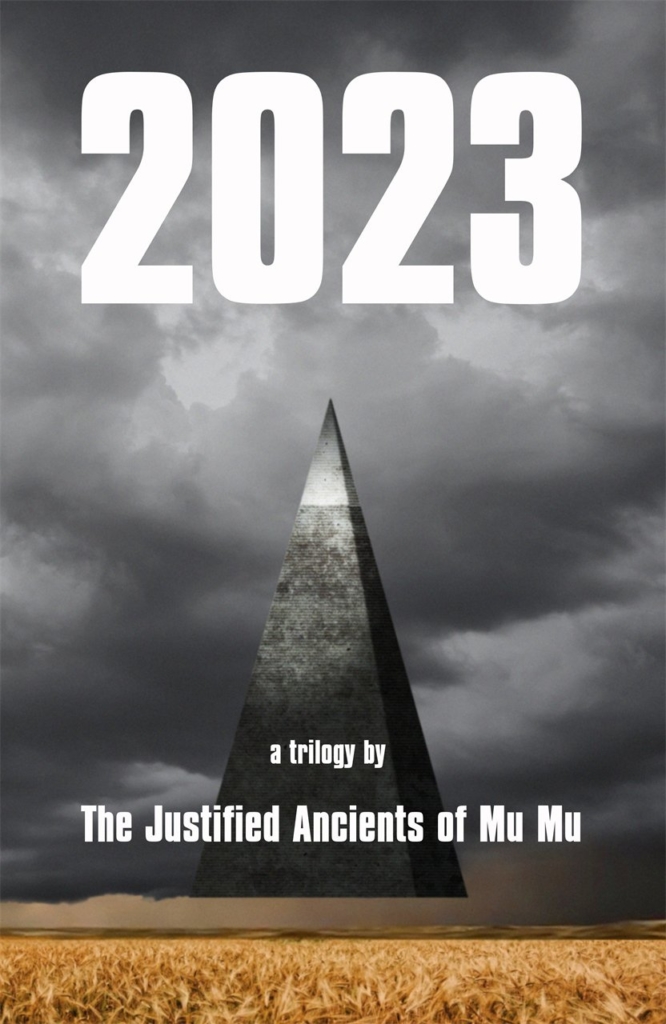

And who knows? Such calculated looking phrasing could be part of an even bigger wheeze. Perhaps F UK* 2022 was inspired by 2023: A Trilogy, the novelistic sprawl penned by Jimmy Cauty and Bill Drummond, writing as one of their former 1980s pop star names, The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu.

*

*

Published in 2017, this epic fantasia by the artists formerly known as The KLF, The K Foundation and many other names besides, was trailed by a poster that appeared in Hackney bearing the urgent inquiry, ‘2017: WHAT THE FUCK IS GOING ON?’ This referenced 1997 (What the Fuck’s Going On?), a 1997 performance by Cauty and Drummond as 2K. This in itself drew from 1987 (What the Fuck is Going On?), the debut album by The JAMS released a decade earlier.

*

Perhaps this was also the spirit being channeled by high street fashion emporium French Connection a few years back when it was reinvented as the infinitely more attention grabbing FCUK.

*

If no semantic shenanigans were even slightly intended, chances are that the Siobhan-Sharpe-from-Twenty Twelve think-alikey marketing types who brainstormed it up will be kept on their toes with how the phrase is used for some time. Either way, F UK* 2022, what is going on? And if The K Foundation isn’t part of it, why not?

*

To Hull and Back

*

F UK* 2022 is headed up by its Chief Creative Officer, Martin Green. Green comes with a back catalogue that includes producing the opening ceremony for the London Olympics 2012. The ceremony was directed by Trainspotting director Danny Boyle, with musical direction by Rick Smith of Underworld. Amongst its many evocations of the subjectively selected best of British culture, the ceremony’s showstopping extravaganza included a celebration of the NHS.

*

Green was also at the helm of Hull UK City of Culture 2017. This year-long series of events in the East Yorkshire located port of Kingston upon Hull included a weekend programme curated by Edinburgh spoken-word provocateurs Neu! Reekie! This included performances by Scottish Album of the Year winners, Young Fathers, plus Bill Drummond, Linton Kwesi Johnson, and a screening by film director Mark Cousins.

*

Green, then, is clearly no flag waving nostalgist on a mission to save some mythical empire. As his track record demonstrates, he is plugged in to pop culture that has mass appeal while remaining artistically provocative. This may have been why Green was hired as executive producer of Edinburgh’s Hogmanay for a couple of years, seeing in 2020 with what might possibly be the last event of its kind for some time.

*

Such are the apparent contradictions at the heart of what has become the inherited baggage of the now independently run F UK* 2022. The list of Scotland based organisations amongst the teams bidding to take part serve up even more food for thought. Two Scotland-only entries have been selected for the R&D Project that will take place between now and February 2021, with further Scotland based organisations joining other creative teams.

*

Edinburgh International Festival and the National Theatre of Scotland join forces with V&A Dundee, Edinburgh Science Festival, Sky Arts, the University of Strathclyde and Dundee based video games company, 4J Studios, to make up one of Scotland’s bids.

*

The other team sees Glasgow based music festival Celtic Connections collaborating with Aproxima Arts, the company formed by former driving force of NVA and Test Department, Angus Farquhar. Also on board with them are BEMIS Scotland – the umbrella body for empowering the country’s ethnic and cultural minority communities – and Dingwall-based Gaelic participatory arts company, Feis Rois. They will be joined by environmental art and lighting company, getmade design, environmental research body, the James Hutton Institute, and the agriculture based Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC)

*

Elsewhere, Dance Base Scotland is collaborating with partners that include the Royal Astronomical Society and the Institute of Engineering and Technology (IET); Edinburgh Napier University joins forces with a team that features celebrity chef Jamie Oliver’s company; and arts development body Creative Dundee are collaborating with partners that include Liverpool based cultural organisation, Metal.

*

With proposals to open a new centre in Dundee, the Cornwall based Eden Project is working with the city based publisher DC Thompson to form an alliance with the Institute of Global Health Innovation and others. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh continues an ongoing partnership with Serpentine Galleries alongside progressive economists, Doughnut Economics Action Lab, and hi-tech design agency, Superflux. The Scottish Association for Marine Science, meanwhile, feature in a bid with a team that includes the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research.

*

In other teams, Pitlochry based conservationist charity, the John Muir Trust, are working with North of England Zoological Society and the University of Cumbria;

and internationally renowned audio visual auteurs 59 Productions, who have worked with the National Theatre of Scotland and the Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh, team up with The Poetry Society among others

Scottish associations among the 30 teams continue, with former Traverse Theatre associate director Lorne Campbell, now artistic director of National Theatre Wales, co-leading the company’s collaboration with partners including the Centre for Alternative Technology, Youth Arts Network Cymru and Disability Arts Cymru. Long-time spoken word producers Apples and Snakes, meanwhile, are working with Trigger Stuff, led by arts producer Angie Bual, who previously led the Govan-based Allotment project with the National Theatre of Scotland.

*

Turner Prize winning design collective, Assemble, partner with the Centre for the Study of Perceptual Experience and the Sackler Centre for Consciousness Science for their bid. Assemble won the Turner in 2015 for their work on reimagining a series of inner city houses in Liverpool. They were presented with their award at the ceremony held in Glasgow, where they exhibited at Tramway.

*

Biting the Hand

*

Given that both EIF and NTS are supported in various ways by the Scottish Government, the presence of both organisations among F UK* 2022’s bidders shouldn’t come as a surprise. Especially as F UK* 2022 is itself funded by the Scottish Government alongside those of the other devolved nations, and is partnered by Scotland’s national tourism body, EventScotland.

Given that both EIF and NTS are supported in various ways by the Scottish Government, the presence of both organisations among F UK* 2022’s bidders shouldn’t come as a surprise. Especially as F UK* 2022 is itself funded by the Scottish Government alongside those of the other devolved nations, and is partnered by Scotland’s national tourism body, EventScotland.

However cannily national arts institutions have to work within the prevailing political orthodoxies of the day, as long as Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland remain tied to the UK, they are unlikely to ignore such high profile platforms as F UK* 2022. This is the case however glaring any political motivation to undermine the self determination of the devolved nations may or may not be.

*

In this sense, Scotland’s national arts bodies are undoubtedly influenced by Holyrood’s arguably enlightened agenda. By contrast, the National Theatre of Great Britain, for instance, has at times had a less harmonious relationship with Westminster. In the current climate, at least, neither approach are necessarily bad things. Whether artists biting the hand that feed them is even an option by the time we get to 2022, however, remains to be seen.

*

Welcome World?

*

Nevertheless, many of those bidding to take part in F UK* 2022 already have pretty strong track records in kicking against the pricks. While some might see Edinburgh International Festival as part of the cultural wing of the British state, internationalism has been at its heart since its foundation in 1947 to ‘provide a platform for the flowering of the human spirit’. This was defined in an even simpler fashion in 2016 when the long planned festival slogan – ‘Welcome World’ – was revealed not long after the Brexit referendum result.

*

It is telling too that EIF and NTS have just collaborated on last weekend’s online production of Hannah Lavery’s play, Lament for Sheku Bayoh. Lavery’s piece was inspired by 31-year-old Bayoh, who, as a child, fled the civil war in Sierra Leone, and who died in 2015 while being restrained by police in Kirkcaldy.

*

In this way, neither EIF or the NTS have shied away from tackling some of the civic and political ills going on outside their front door that reflect a big bad world beyond. The potential sleight of hand within F UK* 2022 looks even more pronounced with the presence of Angus Farquhar’s Aproxima Arts company.

*

Out of all the artists in Scotland who form part of one F UK* 2022 bid or another, Farquhar has perhaps been the most vocal in his opposition to Brexit. Farquhar has been at the vanguard of cultural dissent for four decades. This stems back to his days battering out martial sturm-und-drang in abandoned factories with Test Department during the Thatcher era, to reconstituting the Beltane Fire on Calton Hill, and all the environmental interventions with NVA that followed.

*

More recently, Farquhar took part in Dear Europe, an NTS-run international cabaret held at SWG3 in Glasgow on what was supposed to have been the day of Britain’s departure from Europe on March 31st 2019. As with pretty much everything else since 2016, the UK government made an almighty balls of things, and the grand exit was postponed. Dear Europe’s compendium of bite-size plays and performances went ahead anyway, and became part lament, part show of international strength.

*

Performing at the event with marimba player Cameron Sinclair as Second Citizen, Farquhar gave an emotional testimony of what Europe meant to him after he wrote to every European nation asking them to adopt him as a citizen.

*

Farquhar and Second Citizen also saw in what then looked like a potentially bright 2020, performing at a Hogmanay End of the Decade party hosted by iconic Glasgow club night, Optimo. With all involved waiving their fees, the night raised funds split between the Coalition for Racial Equality and Rights, anti-racist refugee and migrant homelessness charity, Positive Housing in Action, and Drumchapel Foodbank.

*

As Farquhar points out, “I campaigned on the streets against Brexit and made a passionately pro-European work for the National Theatre…. We decided openly to go for this bid because we are in a Scotland-only consortium, and the budget and content of the final work is controlled within Scotland, an avowedly and deeply pro-European country. We are confident that our project will not and cannot be hijacked by the Brexit Right in the UK government. It was only on this basis that we could bid.”

*

While full details of all bids are currently under wraps, Farquhar says that his team’s bid will focus on food poverty, youth unemployment, active travel and local arts activism “on a truly national level” with the aim of creating an adoptable framework for European and international partners. As Farquhar sees it, “It is a once in a moment chance to really try and do something for the whole country.”

*

In terms of how F UK* 2022 might turn out overall, Farquhar points to 14-18 NOW, the five-year commemoration of the First World War centenary that took place between 2014 and 2018. While all events in 14-18 NOW’s programme remained respectful in its tributes to those who took part in the war, much of the work presented took a less orthodox approach than one might expect.

*

Artist Jeremy Deller’s contribution, We’re here because we’re here, was a particularly moving highlight. Created to mark the anniversary of the Battle of the Somme, the event saw everyday public interventions by 1,400 volunteer participants dressed in First World War uniform, who appeared unexpectedly in public places on July 1st, 2016. If anything in F UK* 2022 comes even close to evoking something as poignant, its existence will arguably have been justified.

*

There is a sense that some of the teams bidding to be part of F UK* 2022 possibly see themselves as entryists working on the inside. Others might see such credible names being used as Trojan horses to give what was originally one of Theresa May’s grand follies a patina of credibility in order to help make the current UK government appear – no, really, – enlightened.

*

Migrants in Culture

*

Whether any of this carries any weight with Migrants in Culture or any of F UK* 2022’s other critics remains to be seen. Migrants in Culture is a network guided by ‘a vision of culture without borders’. They have been particularly scathing about F UK* 2022, and, in calling for it to be scrapped, state that ‘We reject the use of culture as nationalistic branding. Cultural workers are compelled to act as ambassadors for UK soft power in order to access this funding.’

*

An open letter from Migrants in Culture has been sent to Martin Green of F UK* 2022, UK Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Oliver Dowden, and Neil Mendoza, who in May 2020 was appointed by the UK government as its Commissioner for Cultural Recovery and Renewal. The letter states that F UK* 2022 ‘capitalises on the racist and xenophobic movements and discourse that have led to Brexit, the Windrush Scandal, the Home Office’s Hostile Environment against migrants, the rise of far-right politics as well as Grenfell, and the endemic racism, societal divisions and inequality.’

*

The letter goes on to call for ‘An immediate cancellation of the festival and the reallocation of its £120 million budget towards an equitable recovery for the arts and culture sector…’ At time of writing, the letter has been signed by more than 600 artists, art workers and arts organisations across the UK.- An Open Letter to Martin Green, the Festival UK 2022 and Oliver Dowden – Google Docs

*

Comedian Josie Long has already withdrawn from her involvement in F UK* 2022 after being made aware of what she called its “nationalistic agenda”.

*

A Radical Road

*

*

Migrants in Culture’s call to arms in part echoes playwright Peter Arnott’s words a couple of weeks ago accepting this year’s Critics’ Awards for Theatre in Scotland’s Best New Play award. This was for The Signalman, presented as part of Oran Mor’s A Play, a Pie and a Pint lunchtime theatre series in Glasgow back when visiting theatres was still possible.

Migrants in Culture’s call to arms in part echoes playwright Peter Arnott’s words a couple of weeks ago accepting this year’s Critics’ Awards for Theatre in Scotland’s Best New Play award. This was for The Signalman, presented as part of Oran Mor’s A Play, a Pie and a Pint lunchtime theatre series in Glasgow back when visiting theatres was still possible.

*

Calling for a radical rethink about how arts and culture might be organised in a post Covid landscape, Arnott suggested that “I think we are going to have to think some pretty radical thoughts about how we organise what it is we do for a living if any of us expect to do anything like it again. I’m talking about upending the entire structure of governance we inherited from the reinvention of culture at the end of World War II… and reinventing it all over again.”

*

Which brings us back to Craigmillar Now. In the yet to be defined new age of the post Brexit, post Covid era, organisations such as Craigmillar Now, Migrants in Culture and others advocating ideas as radical as those argued for by Arnott might point the way to where that new age begins. By contrast, and however it turns out, F UK* 2022 runs the risk of merely marking the end of everything that went before, and which is about to be lost.

*

Play to Win

*

Despite what the ancient Greeks thought when they invented the spoken word scene by putting poetry into the Olympics in a way that would now be branded as a Cultural Olympiad led by an epic opening ceremony, art probably shouldn’t be treated as a competition. Of course, winning awards can inspire confidence, while infinitely more useful financial rewards help keep those creating work alive long enough to hopefully do something else beyond. But judging art shouldn’t be based on who brings the best report to what might look to some as a grown-up version of show and tell.

*

Nor should the £120 million allocated to F UK* 2022 be used as a temporary salve to plug the artistic and economic chasm caused by Covid. Rather, as with every single other industry currently struggling for their collective and individual lives, and as Migrants in Culture point out, arts workers require a security only universal basic income can bring.

*

While the UK government continues to operate a sticking plaster approach that ultimately won’t save anything except their own livelihoods, a more enlightened Ireland announced last week that a key recommendation of its Arts and Culture Recovery Taskforce report was a potential basic income for arts workers. Now, there’s something for both F UK* 2022 and the Scottish Government to think about.

*

Playing the Joker

*

As far as what happens next with F UK* 2022, all of the above may turn out to be purely academic. Only one of the two Scotland teams competing directly against each other will make it through to the final. As for the rest, like an own goal in a Home International, an edition of It’s a Knockout where you’ve already played your Joker, or a Big Brother Does Bake Off Brexit Special, it’s perfectly possible that no other Scotland based organisation is left standing.

What we’ll be left with then is anybody’s guess, though at least massed choirs belting out Land of Hope and Glory on the hour every hour to define what F UK* 2022 ends up being all about will have been headed off at the pass.’

*

*

Nevertheless, one suspects that some or all of the projects that don’t make the final cut of F UK 2022 may be enabled to happen anyway. This might then be an opportunity to bring other partners on board in a way that embraces those who might feel beyond F UK* 2022’s reach. There seem to be plenty of them about.

*

The Global Village

*

In the forthcoming and possibly still far off post Brexit landscape, future generations’ entire experience of Europe might well be gleaned from the likes of the glossy tourist brochure styled froth of hit Netflix show, Emily in Paris.

*

With this in mind, fiddling while Rome and everywhere else feels the Brexit burn might not necessarily be the best internationalist response. If F UK* 2022 isn’t scrapped as Migrants in Culture are arguing for, perhaps Green and co might do well to step outside their great big ginormous events bubble and take a look at what is already happening at a grassroots level.

*

Glasgow based charity Refuweegee, for instance, works with numerous organisations to work with forcibly displaced people arriving in the city. One of these organisations is grassroots live music promoters Sounds in the Suburbs, who are currently running Zoom based fundraising gigs for Refuweegee on the last Thursday of every month.

*

Similarly styled fundraisers for refugee charities have run in Edinburgh for several years under the name Solidarity with Displaced Humans, and continue do so online. These and many, many other similarly styled grassroots bodies fuse internationalism and artistic expression in ways that make a genuine if largely unsung difference. Despite having a much lower profile and little or no government support, such events are arguably equally as important as anything likely to happen at F UK* 2022.

*

Those behind F UK* 2022 should perhaps also take a look too at Craigmillar Now. Here is an organisation steeped in local history, founded on a grassroots model and building on both for a brand new future where the global and the local meet.

*

Beyond the Fringe

*

While it’s probably fair to presume that none of the grassroots organisations mentioned here made their own bid to be part of F UK* 2022, it will be interesting to see how they and others respond. Perhaps they won’t do anything, and will just keep on keeping on with the mighty work they do already. Or perhaps, as some wags have suggested, the high profile presence of F UK* 2022 will provoke dissenting voices to kickstart their own counter event. Such a move would inadvertently conjure up the spirit, not of the 1821 Great Exhibition or the 1951 Festival of Britain, as Theresa May’s display of England’s dreaming predicted, but that of an accidental consequence of Edinburgh International Festival.

*

That event took a sharp turn towards the future after a couple of student theatre companies not officially programmed turned up and decided to do their own thing anyway. From such small but dramatic acorns was eventually spawned the monster of today’s Edinburgh Festival Fringe.

*

With this in mind, it has also been mooted that, rather than similarly brand any F UK* 2022 alternative event as a fringe, that it adopt the model of the Avignon Festival, that other great European arts extravaganza founded in the post-World War Two rubble to promote a spirit of unity. In Avignon, as with Broadway, fringe events are referred to as ‘off’ the official programme. This would make for something that could be legitimately and magnificently referred to as F UK* 2022 Off. My, how that asterisk would wink.

*

Beyond such potential fun and games, the big idea these days for large-scale public events like F UK* 2022 is legacy. In fifty-years-time, for instance, how will F UK* 2022 have affected things, and how will future citizens of whatever country they’re part of by then be keeping its spirit alive?

*

These days such things are more likely to be spun for potential artistic, civic and political capital. Then again, those behind F UK* 2022 might want to see for themselves how such long term side effects can happen organically, democratically and in a way that puts people first. If so, they could do worse than check out Craigmillar Now. Those making things happen there already look like a winning team.

*

Craigmillar Now – www.craigmillarnow.com

The Venchie – www.venchie.org.uk

Festival UK* 2022 – www.festival2022.uk

Migrants in Culture – www.migrantsinculture.com

Refuweegee – www.refuweegee.co.uk

Solidarity with Displaced Humans – https://www.facebook.com/groups/1653384801546439/

Let the People Sing! by Helen Crummy was originally published by Craigmillar Communiversity Press in 1992.

What a comprehensive digest, thank you. So much to follow up, including the confusing and quite enjoyably lurid F UK 22 website :/ I guess there has always been a place for everybody in the arts, but Craigmillar Now will certainly be a success.

Festival UK* 2022 is a prime example of the nationalistic branding of culture.

Touted as a way of supporting the national culture industry’s recovery from the economic downturn it’s experienced as a result of the measures taken by our governments to mitigate the risk the coronavirus pandemic poses to the functionality of the NHS, it could have been used to highlight the diverse and often dissonant communities that comprise civil society; instead, it’s being used to fabricate narratives of national ‘identity’ and ‘solidarity’ that ‘bring people together’, narratives which create a hostile environment for difference and outsiders.

The declared aim – to ‘showcase the UK’s creativity and innovation to the world’ – is impossible because there’s no such thing as ‘UK creativity’ or ‘Scottish creativity’ or whatever flag you want to brand it with. All artists are, in their creativity, ‘stateless migrants’.

So, Festival UK* 2022 has essentially nothing to do with art. At bottom, it’s a commercial initiative that uses the Union Jack as branding.

As consumers, if you don’t like the brand, don’t buy the product. That’s the way the culture industry works.

Two points: if there were no such thing as UK, or Scottish creativity, or wherever, then there would be no such thing as nationally identifiable cultural work. Yet clearly there is. That may form from conscious or unconscious allegiance to certain tropes, but either way, the culture we grow up in has a huge effect on the art we produce. So music (my specialist area) has had distinct cultural, even national, character for many centuries and this has been extensively studied and documented.

Secondly, I always find it fascinating how we use the phrase ‘culture industry’ so casually. What does it mean? I am fairly sure that the term was invented by Theodore Adorno as a pejorative damning of the way culture was being commodified and impoverished in the earlier part of the 20th century: art was becoming just like any other factory product; a production line of sameness, occasionally spiced up a bit to avoid consumer boredom but primarily designed to shift the largest number of units possible. This is a cynical view and Adorno did not always understand culture that well in my view but he was on to something here. I hate the term and I hate the contemporary commodification of art as so much ‘content’. Sadly the culture industry notion is now so normalised, even apparently enlightened funders see it this way and cultural funding has to be defended in terms of how much money it returns. Yet the ‘consumer’ does not give a toss about this really (because they are not consumers of course, apart form in the literal sense, and even then . . . ) – if they are delighted, moved, inspired, angered even by art, that is what they want. They don’t want to know the cost as their lives have already been enriched, challenged, changed even; which is the whole point really.

Thanks for the article btw Neil, really interesting and thoughtful. Hard to know what to think about it all.

‘[I]f there were no such thing as UK or Scottish creativity, or wherever, then there would be no such thing as nationally identifiable cultural work. Yet clearly there is.’

Well, is there? If we take ‘Scottish creativity’ to be the creativity that takes place within the defined territory of ‘Scotland’, then what else is there to mark it out as peculiarly Scottish and distinguish it in kind from the creativity that goes on elsewhere? You’re no doubt right when you say that ‘the culture we grow up in has a huge effect on the art we produce’. But today’s Scots have emerged from a wide range of cultures, which makes their culture as globally cosmopolitan as the next country’s and in no sense ‘native’ or even peculiar.

But, yes: ‘the culture industry’ was invented by the critical theorists, Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, to denote the commodification of cultural forms that has resulted from the growth of monopoly capitalism. The culture industry, they argued, plays a central role in cementing its audience to the status quo, and transforms culture itself into an ideological medium of domination; i.e. the hegemony or ‘mental slavery’ by which that status quo maintains itself.

Against the hegemony of the culture industry, Teddy and Max contrasted what they called ‘autonomous’ art. Correspondingly, autonomous art has an emancipatory rather than a hegemonic character. The emancipatory character of autonomous art stems not from its content, however, but from its atonal or dissonant forms. Therefore, unlike ‘bourgeois’ cultural theorists, they argued that the most emancipatory form of art is not that which contains the ‘right’ moral or political message, because this requires an attempt to work within the existing hegemony of values to demand change from the status quo; rather, it’s that art which, like critical theory itself, compels change through bending those values into disruptive forms and to the point where they break, releasing that vast and creative ‘upswelling of the incalculable’ that produces the future.

Adorno and Horkheimer believed that the function of the culture industry is to extinguish the revolutionary potential of the masses, by providing relief from the stresses of life under capitalism through brief and surface-level distractions; a formulaic and predictable escape from freedom and (with apologies to Norman Tebbit) responsibility that keeps us within the existing social and political boundaries.

I don’t think you can dismiss Scottish or any other culture as ‘globally cosmopolitan as the next country’s and in no sense “native” or even peculiar’ so simply. This would mean there is no cultural distinction between nations or geographical areas. Within the UK the distinctions between Scots, English and Welsh are pretty subtle I agree and too much is made of difference but difference still exists. This does present a bit of an issue for cultural nationalism as it is Gaelic culture that offers the most obvious cultural distinction for Scotland but that is rather remote and disconnected from the now for most people. The kind of music Neil has written about brilliantly on this site – post-punk / the new wave etc is peculiarly British, not Scottish or English but I daresay he might still be able to offer certain character traits of the Scottish scene. Much more easy to distinguish between British culture and French for example and the distinctions are stark – in the classical realm, French music is identifiable in an instant often and the new wave of above barely existed in France as it did not chime for some reason with perceived Frenchness.

I agree though that this tendency of cultural distinction has reduced through globalisation (using the term very broadly) but it hasn’t gone and away and importantly, people don’t want it to go away and if they don’t, it won’t as artists will continue to claim and reclaim what they see as their story as long as they have breath in them and their story will often be one of their nativeness (look at the latest Booker prize winner). Is this a good or bad thing? I err on the former as global uniformity is not a very attractive idea in general and is a bit of a killer for art which strives for distinction if expression. One of the problems with arts’ funding is that it tries to encourage the ‘right’ sort of art, the correct diverse mix and will eschew art which goes against the zeitgeist which at the moment might be to challenge certain dominant progressive (so-called) ideas. Controlling art in this way is to basically impoverish it in the long run though I admit I don’t have a ‘solution’ for how creative people can earn a living and do their thing successfully. I don’t think there is one because art and money run a parallel course with different links made between them but at root, never the twain shall meet; which is a good thing.

Thanks for detail about the Frankfurt school. I know a bit with regard to Adorno and music which he spoke well about but also rather ignorantly of too (he didn’t actually understand popular music). I do like the basic idea of music that either affirms or challenges the status quo and that musical structures can be radically disruptive and empowering in themselves. Trouble is what has happened is that this idea itself has become commodified and neutered! I asked a current modernist composer recently about why he sought to disrupt the listener’s perception so much with his disjointed and erratic formal approach (he was discussing it only in purely music terms). He got quite angry saying he didn’t need a reason but then accepted that it was basically stylistic – he liked it. He is in essence an establishment figure of late high modernism. I suspect Adorno would not have approved. The question therefore remains – what are the structures that can challenge the current status quo(s)?

‘This would mean there is no cultural distinction between nations or geographical areas.’

And this is the ‘end’ of globalisation: a world music, a world literature, a world cuisine, etc.; a free-market of transportable precedents rather than a menagerie of distinct traditions. Some see this as a bad thing; I don’t. ‘Not traditions – Precedents!’, as the sluagh-ghairm goes.

I suppose what I’m saying is that civil society in Scotland is becoming so diverse in terms of the traditions in which its citizens have grown up – that is, in terms of ethnicity – that there is no one tradition that could be unequivocally called ‘Scottish’, and that this is a good thing. In this respect, even more ethnically diverse countries like England – and London especially, the cosmopolitanism of which is sometimes said to be unsurpassed – are far more advanced than we are. These have even less claim to having a definite culture that they can wear like a badge of national identity, which is why such badges as they come up with now and again always come across as racist or otherwise exclusive.

Is the music made and consumed by French citizens who have grown up in non-European cultures not also ‘French’? It certainly doesn’t sound as ‘French’ music is supposed to; i.e. as music made and consumed by those citizens who have been shaped by centuries of European history and, on that basis, assert themselves as the ‘true’ French. Any music made by a citizen of France is French music; even that of the fiddler and boat mechanic, Frankie Begg, my old school-pal who’s now out of Marseilles, who’s been a French national for over 30 years now, and who can still knock out a strathspey or reel after a few pastagas.

Aye, Adorno was a bit of a cultural mandarin and musical snob. He was also an accomplished concert pianist and composer. For philosophical reasons, he studiously avoided issuing prescriptions as to what autonomous art should look like (for those same reasons, he studiously avoided saying anything positive about any ‘future’), conceiving his task to be the purely deconstructive one of immanent critique, which aims to locate and give free play to the contradictions inherent in any present system.

So, ‘what are the structures that can challenge the current status quo(s)?’

Any form will do, providing it disrupts prevailing systems of theory and practice to the point where they collapse under the weight of their own contradictions and release a vast and creative ‘upswelling of the incalculable’ from which the future will emerge.

‘I admit I don’t have a ‘solution’ for how creative people can earn a living and do their thing successfully.’

I wrote a wee article on this at the weekend. It hasn’t found a home yet. I might post it here.

I’d like to read your article: please post!

I think there has a been a reconfiguration of what might be called cultural distinctiveness that no longer necessarily derives from or relies solely on European heritage.

Yes with a city like London (where I am from originally), the diverse peoples produce music that sometimes adheres more to their ethnic background, sometimes in a pretty pure form, like your friend in Marseille but to me that is only nominally ‘French’ in that music is made within the borders of the nation.

But there is something else: take grime – this music’s roots is largely Jamaican and American and yet it is still a distinct London and indeed English music and those who make it (mostly black musicians) actually pride themselves on this. The distinctiveness can be found in the details of the music and lyrical concerns and the fact it is derived from an earlier similar form (drum and bass) so has its own ‘English’ heritage now (I have heard similar but distinct variations coming out of Glasgow too). It isn’t Elgar but then who says there has to be a monolithic idea of culture? England is an incredibly diverse country and despite what is sometimes said on here, not at all insular, quite the opposite, despite its somewhat bigoted turning of its back on the EU. I live in a relative backwater of West Yorkshire and even here it is made up of people from all over and the cultural mix is impressive but somehow ‘Yorkshireness’ still prevails and can encompass all of the people as Yorkshireness is itself changing.

I tend to adhere to the idea that today it is in the way you mix and match that creates cultural distinctiveness rather than there being some mythical root to it all that only ‘natives’ can access thus barring migrant cultures from expressing cultural Englishness or Scottishness or whatever. In other words as people coalesce, new distinctivenesses emerge. Maybe this is is the same as your ‘precedents’.

The inclusiveness thing seems a bit of red haring to me as that is a political issue rather than a cultural or aesthetic one. Not everyone can or wants to be included in everything and the current cultural appropriation wars suggest some actively want to keep people out. I don’t agree with that and I think they will fail in the end but I don’t have a problem with some striving for culturally more ‘pure’ products, even ethnically so, just because it might exclude me. I will just enjoy the outcome if it’s any good and being steeped in a narrow culture can produce some great art.

I suppose what I’m wondering is what makes the multiculturalism of Yorkshire distinctively ‘Tykish’ and that of Scotland distinctively ‘Scottish’, other than geography and political constituency; in what does the cultural difference of those two populations now consist, given the widening and deepening cultural diversity that is making both populations virtually indistinguishable in the range of their beliefs and practices.

Isn’t this difference now little more than formal; a residue of the real historical differences that previously existed between the two fairly homogenous ethnic groups that once dominated those respective populations?

What makes a Scot of Pakistani heritage distinctively ‘Scottish’ in comparison to a Tyke of Pakistani heritage, other than the fact that one participates in the civic life/is a constituent of Scotland as a polity while the other participates in the civic life/is a constituent of (say) West Yorkshire?

Is nationality not now more about shared citizenship than about cultural distinctiveness?

(But we’ve been here before.)

ART IN THE TIME OF COVID

*Art for art’s sake, money for God’s sake!*

Art for art’s sake is a modernist doctrine. It was first put about by fin de siècle artists who believed their art should be created not for commercial purposes, but for the sake of greater creative exploration and self-expression.

But artists need ways to sustain their work. So, the question then arises:

*Should artists try to monetise their work, or is this to devalue it?*

When I wrote, I never tried to market my work. This wasn’t for any principled reason. I just couldn’t be *rs*d. Once I put my pencil down – or, latterly, when the clack of my stuttering keyboard subsided – I didn’t want anything more to do with my words. They’d been said, as well as I could say them. I was also in the happy position of being otherwise employable and serially employed; so I didn’t need the money.

I justified my lack of enterprise by telling myself I was in good company. Vincent Van Gogh and El Greco are two of the greatest artists in our history, and they were largely unknown during the time they were alive. They enjoyed commercial success only posthumously. They may be considered ‘great’ because, beyond the quality of their work, they remained ‘true’ to themselves; they persisted and continued to create in the manner they wanted to do, in spite of the lack of sales.

Modernism sees art and business as two incompatible activities. Through the process of making, artists give objective expression to the subjective truth of their own life experiences; businesspeople, in contrast, make money.

Of course, the two things aren’t really incompatible; it’s possible to do both. But nevertheless: to make money from their art, artists must first and foremost make objects that will sell; if they can also, by happy accident, recognise themselves in those objects, then so much the better.

*Kurt Cobain and art as a commodity*

Modernist aesthetics no longer dominate art, however. Commodification, rather than authenticity, is the ultimate touchstone of all value in the postmodern world; that is, in the world that emerged in the second half of the 20th century as a sublation of the barbarism into which the modern world deconstructed in the first half.

An artist who completely grasped the commercialisation of art in the postmodern world was Salvador Dalí. Another was Kurt Cobain. The so-called ‘King of Grunge’ was the frontman of the rock band, Nirvana, which is credited with bringing indie rock into the mainstream of commercial music.

Despite the global success of Nirvana, Kurt was at the time often portrayed by his marketing machine as an unwilling participant in his band’s fame. Ironically, his unique selling point was that he outwardly rejected the commercialisation of music and despised the press junkets and promotional aspect that was part and parcel of the business.

*Serving Mammon*

In his 2019 memoir, Serving the Servant: Remembering Kurt Cobain, Danny Goldberg, Nirvana’s former manager, writes of how Kurt envisioned Nirvana attaining global recognition and strategically planned to ensure that it did.

Goldberg describes how Kurt possessed a ‘comprehensive, crystalline understanding’ of how to resonate with audiences over different media and was involved in every aspect of the band’s marketing, from designing its album cover-art to overseeing the direction of its music videos. Beneath the façade of a reluctant rockstar, Kurt was commercially invested in engineering Nirvana’s international success and maintaining the band’s external image.

Which just goes to show how, in the postmodern world of global capitalism, every rebellion against global capitalism becomes itself a marketable commodity, such is the insidiousness of its hegemony. That insidiousness, rather than mere geography, is what makes it ‘global’.

*So, when the *rs* falls out of the market…*

The problem for artists is that, once their art becomes their business and they begin to quantify its value primarily in terms of media consumption and public reception, they begin to look at it differently and to devalue it if it isn’t received well enough; that is, if it doesn’t sell.

But in the midst of a global pandemic, our ‘creative industries’ are, as we keep hearing from the sector, currently struggling to find customers. This commercial crisis is leaving artists in the lurch of a depressed and therefore ultra-competitive market. Many are finding their businesses going to the wall. Such is market economics.

Perhaps, the solution is for artists to leave the industry, return to the places within themselves that are the source of their art – to the subjective truth of their own life experiences that, as artists, they’re moved to objectify – and find other ways of getting the money they need to sustain this, their real work. Perhaps, as so many artists in the old modern world did, they need to find jobs.

And if their real work produces art that others want to consume and are willing to pay for the privilege of so doing, then all well and good. But artists shouldn’t make their art hostage to commercial success.

Danny Goldberg, Serving the Servant: Remembering Kurt Cobain

https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B07J5RR7S2/ref=dbs_a_def_rwt_hsch_vapi_tkin_p1_i1

Thanks for this article. Many aspects to think about and many possibilities it seems. The richness of the local is too often overlooked and what a shame.

I’d be very interested to hear if Neil’s thoughts on FUK*2022 have progressed as we get closer to happening?