Housing Crisis – the Burning Issue. It’s time we stopped fanning its flames.

By Joey Simons, Norman Cunningham, and Angela McCormick.

Scotland is in the midst of a housing crisis: Scotland’s people know this and need more than ongoing repeating of it. We need bold leadership from the Scottish Government to introduce a restorative, ambitious and environmentally friendly approach to public house building, alongside curbing the rental market that is already out of control (see our previous piece here). A tragedy of the commons wrought by our nation’s radically right wing parliament in the worst days of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown has slowly burned into a wildfire of debt, misery, landlordism and exploitation affecting our nation’s working class, with the Scottish Government acting too slowly, or as often as not fanning the flames.

To much fanfare the Scottish Government’s Affordable Housing Programme introduced in 2011 was set to shine a beacon of hope in a landscape blighted by mass housing demolition. That hope has proven oversold, and we stand on the edge watching profit fuelled flames consume our communities, armed with policies fit for a bygone era.

Let’s first explain the context. Until 2007 a fast rolling campaign of extremist wholesale stock transfer and mass demolition of public housing was enacted by the Scottish Executive. There were various bureaucratic reasons for this alongside pervasive right wing ideology, but principally this was an attack on the vision and purpose of public housing, with Gordon Brown’s stated goal to reduce public housing stock (both Council and Housing Association) to just 5% of all housing in every UK local authority[1]. In local authorities like Glasgow or Inverclyde the effect was devastating. In Glasgow City Council, council housing properties were transferred to the Glasgow Housing Association (GHA) with over 85,000 properties being hived off. The GHA then succeeded in demolishing nearly 40,000 houses[2], and at one point stated their intentions to tear down every high rise block in the city, regardless of the social or environmental cost, and which changed the tenure balance of Glasgow’s remaining housing stock. Bear in mind the environmental insanity of this. The average single flat has around 80,000kg of embodied carbon[3] in its construction – that historic CO2 emission is just entirely wasted with housing demolition: it is the most enormously wasteful thing our society does in fact. You could drive the average city car for 100 years and not emit as much CO2 as demolishing one flat emits. In total, this program resulted in 66,000 public homes being demolished[4], largely before 2007.

After the crash as we know we had a change of government, with the SNP winning power from Labour. The Scottish Government sought to intervene in a new way in housing several years thereafter with its Affordable Housing Programme. The programme was aimed at addressing shortfalls in housing, and as the name suggests, making housing more affordable, as well as providing much needed economic stimulus over the course of two parliaments. The Scottish Government has been at pains, as late as September this year in fact, to point out that new build homes are being built and completed at a 12 year record.

“There were 22,386 new build homes completed across all sectors in Scotland in the year to end December 2019, an increase of 11%, or 2,291 homes, on the previous year, and the highest number of homes completed since 2007. There have been increases across private-led completions (9% or 1,380 homes), housing association completions (14% or 536 homes) and local authority completions (31% or 375 homes). There were 23,672 new build homes started across all sectors in Scotland in the year to end December 2019, an increase of 1,639 homes (7%) on the previous year, and the highest number of homes started since 2008.” — Housing statistics quarterly update: September 2020

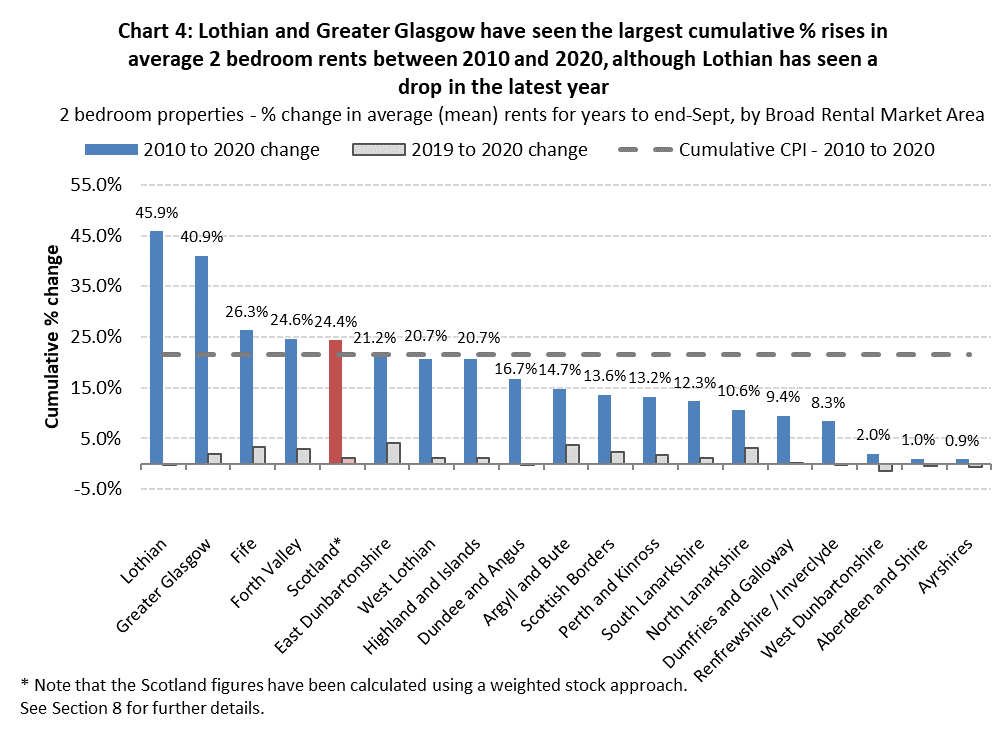

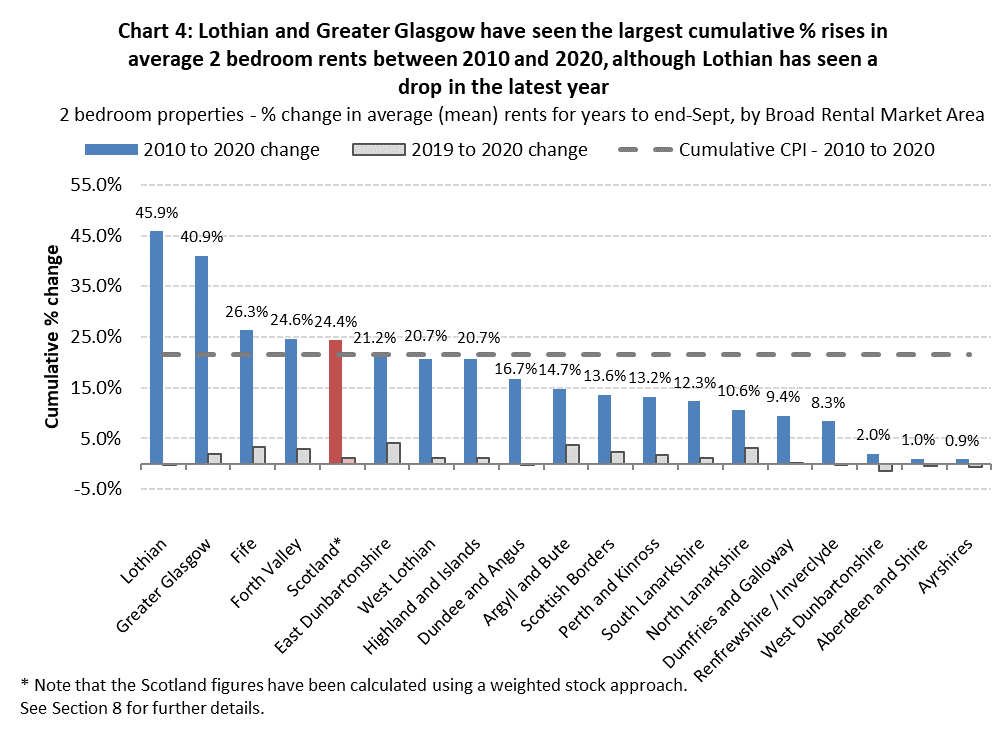

Yet despite this apparently positive picture, housing demand and rent rises continue to accelerate. Rent rises in the private sector have been the most dramatic (see Chart 4 below showing the pressure in the private rented sector) however they are significant in public housing as well : “Over the last decade (since 2007/08) the average weekly council rent for social housing has increased by […] 13% in real terms which is over and above general inflation[5]” Indeed, the Housing Regulator has spoken out about this trend too: “many landlords use the September or October inflation figure as the starting point for their proposed rent increase for the following year […] we are seeing signs of inflationary pressure starting to build in rents,[6]” Noted the authority’s Chief Executive.[7]

Indeed, alongside these pressures on rents is the increasing lack of availability of housing. I’ll leave it to landlord body CityLets to describe the private rental market in Glasgow and Edinburgh this year.

Edinburgh: “One-bed properties, in particular, were snapped up quickly by prospective tenants at just 17 days on average TTL. 83% of One-bed properties and nearly three-quarters of all properties (74%) let within a month. The average annual growth for the Edinburgh rental market has been just over 5% from both the five- and 10-year perspective.” And, Glasgow: “One-bedroom properties took just 15 days on average to find a tenant and 85% let within one month. Overall, 78% of Glasgow rentals let within a month. The average property to rent in Glasgow now stands at £802 per month and is expected to remain above the £800 mark throughout 2020. [8]”

In the social rented sector too, despite the innovation of the Prevention system for homelessness, there are still over 100,000 applicants waiting on a Council house, and of these households there are 40,000 families, with 70,000 children among them or (one in twenty children).[9] There are clearly not remotely enough public houses for would-be tenants to access.

Once we look at the Government’s own statistics of tenants living in poverty after we factor in their housing costs, what we find is stark. Before the Affordable Housing Programme 33% of tenants in public housing lived in poverty. Today that figure is 40%[10]. The position for owner occupiers has not moved at all in that time, and a third of private tenants continue to face the same hardship they did before the programme. in summary rents and poverty have broadly increased, housing demand far outstrips public supply and despite 50,000 new homes, 35,000 of them public housing, the problems are escalating.

So why, despite this 12 year record of new builds are we still seeing this misery, when clearly there are lots of new build developments, including by some housing associations? We need to drill down.

Change in tenure

At the advent of the Scottish Parliament this was the nature of housing tenure in Scotland.

25.3% of people lived in Council housing.

5.7% of people lived in a housing association.

6.7% were private tenants.

62.3% were owner occupiers.[11]

Today (2018 figures, the latest national breakdown by tenure published by the Scottish government), this is the position.

12.1% are council tenants.

10.8% are housing association tenants.

14.2% are private tenants.

59.1% are owner occupiers. [12]

Since the start of the government’s affordable housing programme the number of owner occupiers has declined (down from, so too have housing association tenants (down from 11.0%) and Council tenants (down from 12.8%) have also decreased in numbers. The private rented sector across the last two parliaments however has grown by 2%, or 67,000 more exploited households. What we know from the data is that the private rented sector has the lowest standards, and the highest costs.[i][13]

The effect of stock transfer too needs to be factored in. “The average weekly rent for a social sector property in Scotland in 2017/18 was £76.23, an increase of 2.4% on the previous year. Housing association rents averaged £82.28 per week, 16% higher than local authority rents of £70.73.”[14] A transfer of tenants from publicly accountable Council housing to large mostly publicly funded but private housing organisations like the Wheatley Group (the largest landlord in the country, born from stock transfer) has come at considerable cost to tenants.

We also need to look at another aspect of the picture.

Ending right to buy has not been enough – 500,000 homes in Scotland were acquired under right to buy.[15] Increasingly these homes are being sold on to private landlords. In our branches what Living Rent tenants are seeing is large family homes acquired under right to buy being sold off to institutional investors, who are cash buyers, making offers on the first day a property is listed for sale, whose intent is to re-let the property for Houses in Multiple Occupancy (HMOs). Registered social landlords and first time buyers would like to access these homes but they cannot compete with cash buyers with very deep pockets. The net effect is the ever growing weeping sore in communities of family sized homes being parcelled up into HMOs and re-let for rents that far exceed those of the social landlords these former public homes are situated in. This acts as an accelerant to rental increases in working class neighbourhoods, and increasingly traps families in the expensive and still very insecure private rented sector.

Nevertheless billions have been invested in the Affordable Housing Programme. It has been a cornerstone of public policy. So where has the money gone? What’s went wrong?

Well, lots of money has been spent funding tenures which have marginal to counter-productive effects. The UK as a whole has been engaged in volume house building for private sale at scale since the 1970s. In that time home ownership has actually gone into decline. The problem is that homes for first time buyers have become homes for first time sellers. The seller can pocket the difference in the rise in equity and access the property market, but those not on the ladder are priced out. In Glasgow the average house price is now £193,300[16] (up £47,518 since the Affordable Housing programme began) – bear in mind this is in a city where the mode average wage is lucky to scratch the minimum wage.[17] These trends – rising rents, to pay for rising mortgages, with buy-to-let landlords increasingly acquiring much of the private housing stock on sale in working class areas, point to the failure of building yet more private housing, while doing nothing to regulate its resale.

“when we look at last year’s completions for the affordable housing programme roughly 1/3 of all of the ‘affordable housing’ constructed was for some form of owner occupied housing or the doublespeak of “mid-market rent” (expensive rental properties run by housing companies and housing associations, which generally debar tenants from claiming benefits where landlords perform background checks on tenants to ensure they are high earners). This is a huge amount of public subsidy into what is actually fanning the flames of the housing crisis.”

Moreover when we look at last year’s completions for the affordable housing programme roughly 1/3 of all of the ‘affordable housing’ constructed was for some form of owner occupied housing or the doublespeak of “mid-market rent” (expensive rental properties run by housing companies and housing associations, which generally debar tenants from claiming benefits where landlords perform background checks on tenants to ensure they are high earners). This is a huge amount of public subsidy into what is actually fanning the flames of the housing crisis.

“Friends of the Earth recently found that the Scottish Government’s own Building Scotland fund has largely been used as a cash subsidy for yet more expensive private housing. As the Ferret styled those findings, “Private developers get £100m from housing funds but build just 700 affordable homes” “

Drilling down further however we find deeper problems in the way public money is being disbursed. Friends of the Earth recently found that the Scottish Government’s own Building Scotland fund has largely been used as a cash subsidy for yet more expensive private housing. As the Ferret styled those findings, “Private developers get £100m from housing funds but build just 700 affordable homes”[18]

Battles over vacant land

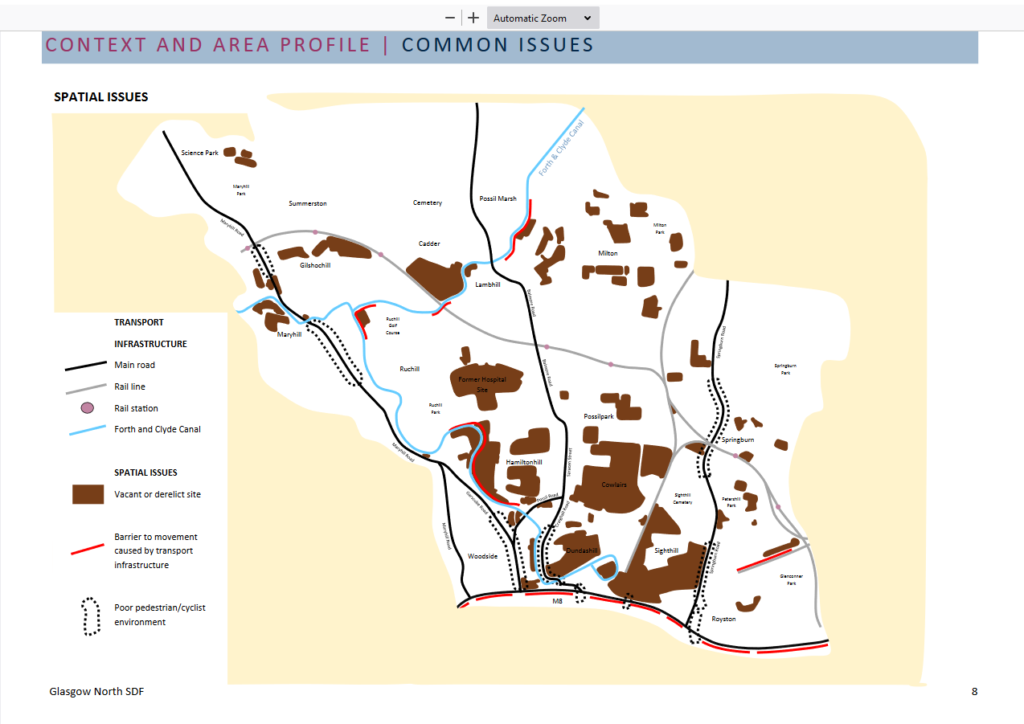

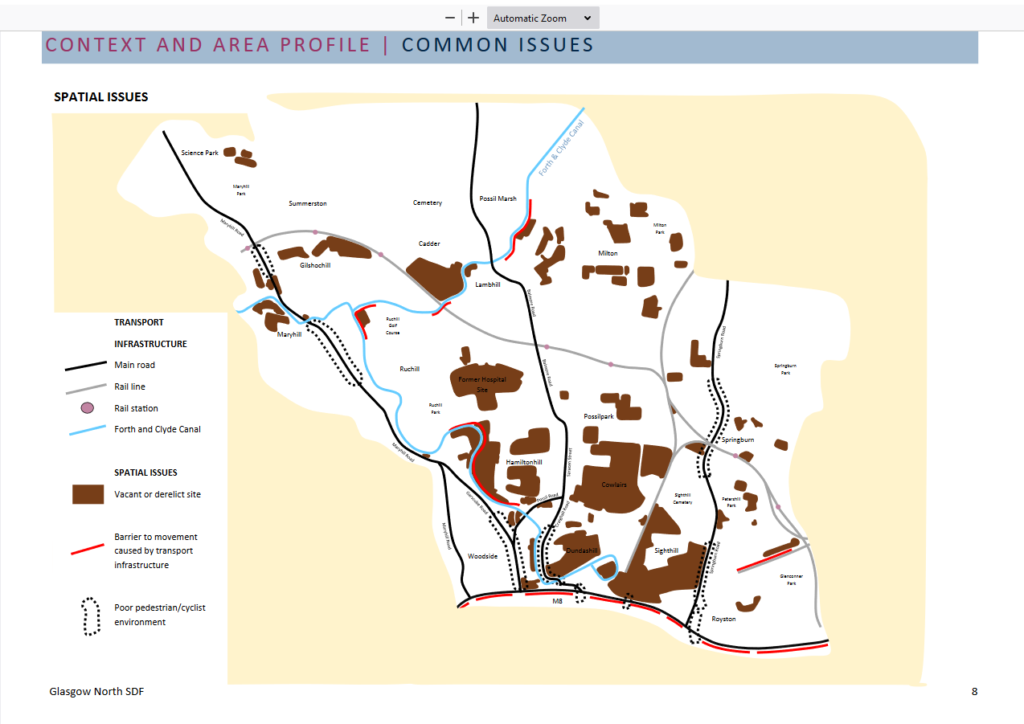

Vacant land in North Glasgow – much of it vacant from public housing demolition – is being considered by Council authorities in a tenure blind way, despite the history, and despite the escalating housing crisis.

When we get into what the union’s own findings are the situation becomes starker still. Let’s turn to look at what these trends mean for two of Living Rent members’’ battlegrounds.

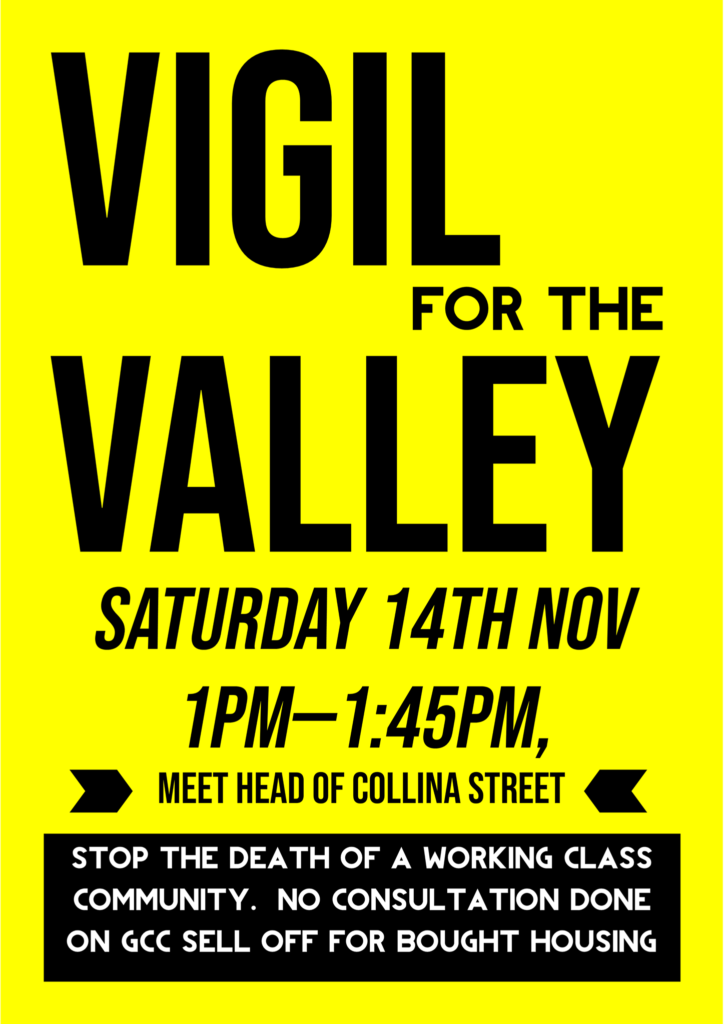

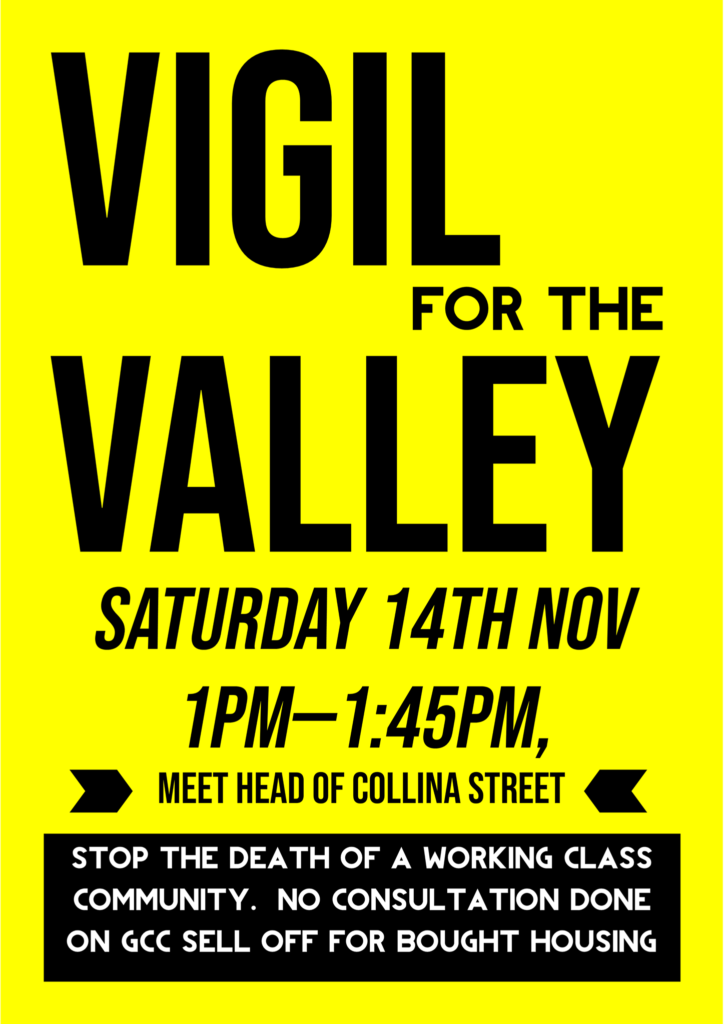

Collina Street

Collina Street was home to The Valley scheme , which was demolished in the mid noughties. It is 2.14 hectare site and sits on arguably the bonniest part of Maryhill, with commanding views over the city and access to the Forth and Clyde canal and Kelvin water. Any development which takes place there will be prestigious, forming the centre of Maryhill Locks developments. It came to great concern to residents to see that Glasgow City Council is in the process of selling this vacant land off to whichever private housing developer bids the most for it, and has strictly instructed that only bought housing may be built here. No adequate consultation has ever been conducted with the local community over whether such much loved public land should be sold off in this radical way, and to such little gain for local people, not least those who used to live in The Valley.

“Collina Street was home to The Valley scheme, which was demolished in the mid noughties. It is 2.14 hectare site and sits on arguably the bonniest part of Maryhill[…] Glasgow City Council is in the process of selling this vacant land off to whichever private housing developer bids the most for it, and has strictly instructed that only bought housing may be built here.”

Unfortunately Collina Street is not an outlier. Elsewhere in Pollokshaws, tenants tell of plans for redevelopment of vacant land, such as the Riverford Gardens development, which originally promised mixed communities now being developed for exclusively private housing. In the case of Riverford Gardens, part of the Transformational Regeneration Area, of 174 houses, 77 were planned to be for social rent. By the time construction began however this had been reduced to zero houses for social rent.[19]

Planning policies for the development of vacant land are often ‘tenure blind’ – in that they do not stipulate that land must be developed for public housing; Councils have the power to enforce a proportion of socially rented accommodation in all new build developments, but Councils such as Glasgow City explicitly refuse to use these powers. The tenure blind basis of such planning policies have in places effectively mandated this gross sell off of the crown jewels where former public housing or public buildings were to the fore. In the much publicised development at Ruchill hospital, former public land is proposed to become a scheme of substandard owner occupied homes with two driveways in a gated community, felling mature trees, ignoring new active travel corridors and providing no public transport infrastructure for houses that will be heated by individual gas combi-boilers in an area of Glasgow officially mandated as central to the roll out of new district heating. While developments like these are not funded by the Affordable Housing Programme they are a huge chunk of what is being developed at any given time.

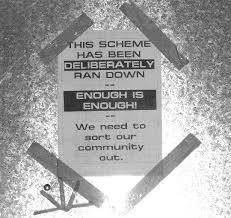

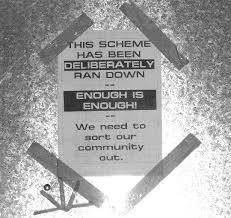

(image: Hamiltonhill protests from 2009)

This is a key reason and context for why in the round the lack of a break with housing orthodoxy over building bought housing, in the Affordable Housing Programme, for the purpose of supporting the expansion of home ownership is fundamentally misguided. In fact, the combined effect of all of these developments is inflationary toward asset values, and promotes the private rented sector. The Affordable Housing Programme does not exist in a policy or a spatial vacuum. For instance, up the brae sits Hamiltonhilll, which was a battleground in the mid noughties over the policy of housing demolition – the tenants lost.

Housing Associations, which have routinely pursued above inflation rent rises for the past decade or more, are salivating at the prospect of higher rental properties, and the chance to act as housing developers for private housing. Nestled next to the Ruchill hospital development is the vacant land owned by Queens Cross Housing Association at Hamiltonhill. All of the public housing on this land was demolished and only the private houses were retained. Queens. Cross Housing now plans to build owner occupied flats to take advantage of views and is giving these pride of place in the developments there. ‘To ensure the highest possible return from the sales, this has meant that the private sales are generally situated in the more favourable locations ‘. The community are asked to be thankful for their exclusion as the only way to fund improvements that they have been waiting twenty years for, ‘the income from private sales is key to delivering the wider masterplan proposals promoted by the community’.

“In the much publicised development at Ruchill hospital, former public land is proposed to become a scheme of substandard owner occupied homes with two driveways in a gated community, felling mature trees, ignoring new active travel corridors and providing no public transport infrastructure for houses that will be heated by individual gas combi-boilers in an area of Glasgow officially mandated as central to the roll out of new district heating.”

Most worrying of all perhaps is the unquestioning push for private sales from a public housing provider ‘The Association had no issue with the requirement to provide at least 50% of the new homes as private sales, as it believes, like the Council, that a mixed tenure development is more sustainable and it would have little interest in delivering 670 new social houses in the area.’ The 100,000 people on the council housing waiting list do however have a very strong interest. Another argument repeated without question is the need for ‘mixed tenure’. We have mixed tenure due to decades of right to buy with streets containing neighbours in private and public homes living side by side. The current developments in Hamiltonhill do not ‘mix’ people they separate them. Entire blocks of flat with only private homes. This builds in division and in no way to create sustainable communities. Isolation of private homeowners form public is deemed to ensure a higher profit. All of this is taking place in an area with some of the highest health inequalities in Scotland and where demand for good quality public homes remains high. It may be the location , five minutes form the West End, the canal and the city centre, which presents too much of an opportunity for rising house prices.

Again we see the same pattern, public land, formerly providing public housing, disposed of to build private housing. The association’s recent business plan, with a barely subdued nod to the gated community at Ruchill hospital and the role of private housing in the redevelopment of Hamiltonhill, boasts of this commercial opportunity, “our aim is to have fixed the city’s perception of Queens Cross as being one of the most popular and vibrant parts of Glasgow. An attractive, desirable community.”[20] Assuming that the Scottish Government is re-elected, this new privatisation of public land by such developments is likely to be funded by any successor funding mechanism to the Affordable Housing Programme.

This process runs deeper than just these battles too – vacant land, just as the weeping sore of the wet deserts occupied by the grousemuirs, is a battleground over the sort of Scotland we aspire to, and what will be the ultimate legacy of people cleared from their homes.

Let’s remind ourselves, since we got our parliament back, Scotland demolished 66,000 public homes, and sold off nearly half a million more through right to buy, ultimately leading to the takeover of our public housing in places by rapacious private landlords. We can stop this. We must stop this. Poverty and despair is rising, but we still have opportunity to change this. The only force that ever changed anything is organised people.

2021 can be the year that we stood up to urban clearance, profiteering landlords, and the misadventure of selling off the crown jewels of our urban environments to private housing developers who we then fund to build poor quality bought houses that get sold on to landlords. This is the process that has done so much damage, and created so much housing pressure.

This is why Living Rent is calling for (1) Fighting the growth of buy to let landlordism in our communities, and (2) Restorative justice for vacant land in all new public housing, to maximise public housing, along with effective rent control measures. This from our manifesto:-

Increasingly former public housing is becoming a vehicle for buy to let landlords, negatively impacting on housing schemes and their residents. We propose that before any house privately acquired under right to buy legislation is resold on the open property market, that the local RSL is given the first right of refusal over whether it wishes to make an offer to buy the property.

Dealing with the long term impact of mass demolitions of public housing, which in the past twenty years saw 66,000 homes demolished, largely unnecessarily, with great environmental impact, we propose that “vacant land”, particularly where these demolitions took place, should be a focus for the redevelopment of public housing. We believe that sectoral demands for 53,000 new affordable homes do not fully address the shortfall, but furthermore that it is particularly important in terms of restorative social and environmental justice that the site of former public homes is the location for new public housing developments. Given the enormous environmental impact of public housing demolitions it is paramount that new housing is constructed to last, built to the highest environmental standards, fit for purpose, incorporating district heating and rated for maximum energy efficiency, with technologies such Passivhaus or similar approaches (e.g. those proposed in Our Common Home Plan).

However we are not just calling for these things to be done, we are actively building local campaigns across the country to force these measures to the highest political level during the next election, and to demand that local politicians seeking community support, get behind organised people standing up against the forces of urban clearance. It’s time that we did more than tinker or fan the flames of the housing crisis but smuired it right oot. This is the coming year to do that. Join our offensive today.

Notes

[1] https://www.qcha.org.uk/assets/000/000/257/QCHA_Business_Plan_20-25_-_Consultation_Document_original.pdf?1601484107

[2] https://www.landlordtoday.co.uk/breaking-news/2020/2/average-rents-in-scotland-increase-3-5-year-on-year–citylets?source=newsticker

[3] Shelter here (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-54226244)

[4] https://www.gov.scot/publications/rent-affordability-affordable-housing-sector-literature-review/pages/5/

[5] https://www.gov.scot/publications/housing-statistics-stock-by-tenure/

[6] Ibidem

[7] Shelter, JRF et al.

[8] https://www.gov.scot/news/social-tenants-in-scotland-2017/

[9] Shelter, ubic

[10] https://www.zoopla.co.uk/house-prices/glasgow/

[11] https://www.glasgowlive.co.uk/news/glasgow-news/key-workers-glasgow-living-wage-18033526 et ubic

[12] https://theferret.scot/scottish-government-housing-fund-100m/

[13] https://www.gov.scot/publications/housing-revenue-account-statistics-scottish-local-authority-housing-income-expenditure-1997-1998-2017-18-near-actuals-2018-19-estimates/pages/3/

[14] https://www.scottishhousingregulator.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/Effective%20dialogue%20with%20tenants%20on%20rent%20levels%20is%20crucial_0.pdf

[15] https://www.gov.scot/publications/private-sector-rent-statistics-scotland-2010-2020/

[16] Sarah Glynn, Scottish Tenants Organisation 2005-2010

[17] Ubic.

[18] https://citu.co.uk/citu-live/whats-the-carbon-footprint-of-an-apartment

[19] https://www.gov.scot/publications/housing-statistics-conversions-and-demolitions/

[20] https://www.qcha.org.uk/assets/000/000/257/QCHA_Business_Plan_20-25_-_Consultation_Document_original.pdf?1601484107

A problem amongst many resulting from deregulation policies by our UK Tory and Labour governments in a false belief that everyone benefits.

The best way to resolve the issue is by reforming how our UK government regulates things including itself: An alternative way is for us in Scotland to make the changes through independence.

Our SNP government objective is for Scotland to become independent but beyond that it will be down to Scotlands people to make the changes required reality.

Politicians are a group of organised people who are making changes, we the people need more power than just elect politicians: The systems we have must change in order to achieve our goals and protect our families and our planet.

Excellent document

Not just commentary but a call to action

I learned a lot from this article. There are not enough articles like this around. Too many of the “researched” and “in depth” reports come from inside the Industry. I worked as a community worker for QXHA at the time they acquired Hamiltonhill from GHA. I wasn’t involved in the stock transfer, however, I’d be very surprised if tenants voted for the stock transfer, in the knowledge that their homes would be subject to demolition soon after.

My personal experience of tenant ballots is as a tenant of Bellsmyre HA in Dumbarton. We have been through two in recent years. The most recent was during lockdown. As I’m sure you’ll appreciate, a tenant ballot is only sound if tenants are well informed of the pro’s and con’s of the proposal. Unfortunately, this hasn’t happened in Bellsmyre or in other HAs I have looked at.

This is no secret and a formula needs to be followed in order to make the claim that tenants are well informed. The formula includes the HA hiring an “Independent” tenant advisor. We have been “informed by TPAS (Scotland) and TIS. Both deemed to be reputable organisations in tenant support.

My dealings with both is that they seem to have the tenants interest at heart in the same way as the landlord. At best, they have a limited grasp on issues from a tenants point of view. At worse, they misinform, twist, and sometimes don’t answer questions when they are too difficult. They actually get an easy time with tenants, as tenants have been misinformed for years by the HA’s, who are the only source of information.

As we know from the history of social housing in Scotland, when the tenant’s experience is cut out of decision making, the decision making is eventually exposed as dreadful. But, not before the money is spent and the decision makers have pocketed the personal benefit of their decisions and moved on.

Living Rent is at least putting a dent into the existing decision making structure. I wonder how practical it would be to take what Joey, Norman and Angela have done here and apply the same scrutiny to individual tenant ballots.

I see from a quick google of “TIS tenant ballot” that they are informing Thistle tenants in Toryglen at the moment. They’ve held their tenant ballot, so it may be too late for tenants there.

TPAS on the other hand have just been announced as the Independent Tenant Advisor for Pentland HA.

https://www.scottishhousingnews.com/article/pentland-and-cairn-resume-partnership-talks

I don’t know how well organised Pentland tenants are. Even if they’re well organised they are up against the might of a HA, The Scottish Housing Regulator, and the Scottish Government. There’s probably also an “investor” powering the whole proposal along.

All I suggest is that you keep an eye on the information tenants receive. I don’t believe in outside interference. However, if you see tenants are not getting all the info they need to make an informed choice. If you can see that tenants are not seeing the pro’s and con’s, then maybe there needs to be an independent group to give the ballot some balance.

For me there is so much wrong with this piece that is difficult to know where to start. I think I will settle for pointing out that the Scottish Government did not invent or start the affordable housing supply programme in 2011. Investment in social housing by the Scottish Government, the Scottish Executive and the pre devolution Development Department of the Scottish Office has a history going back to the 1980s and beyond. What the Scottish Government did in 2011 was cut both the total size of the programme and grant rates. Prior to 2011 grants for new social housing were structured in such a way that pretty much the whole cost of a new home fell either on the tenant living in it (based on a calculation of how much of a loan an “affordable” rent could service) and the tax payer. Grants typically ran at 80-90% of the cost of development for some specialist housing they were 100%. That system was introduced in 1989. In 2011 it was unilaterally torn up and fixed grant rates were introduced with some flexibility for rural areas and highly adapted houses. The basic grant rate was £30,000 a house for Council tenants and £50,000 for RSLs.

This was a deliberate move to shift the cost of new social rented homes onto social housing tenants. Grants were raised in 2013 when it became clear that the programme was falling apart because landlords weren’t prepared to raise rents to make up the shortfall. They were raised again in 2015 for the current programme. Councils now get £58K per house and RSLs £70k. As things stand Council tenants pay around 60% of the cost of a new home, RSL tenants pay around 50%. It’s one of the reasons that rents in the social sector have been rising ahead of inflation for the past 10 years. But as at today, the Scottish Government’s position is that £83pw is an affordable rent for a two bed flat, for a seven person home £109pw is the official “bench mark” affordable rate. These figures will rise by 2% a year for the next three years.

I would agree that we have huge problems in the Scottish Housing System, the growth in private renting is definitely one of those problems, the delay in the abolition of the right to buy (until 2016, it should have gone in 2001) would didn’t help, public policy towards owner occupation and the provision of subsidies to home buyers including first time buyers, a policy that the current Scottish Government has continued and extended in recent years, would be another one. But to pretend that all our problems can be put at the feet of previous governments is not just historically ill informed but also hugely unhelpful when it comes to a proper assessment of what has been achieved in the last 20 years or what needs to change over the next 20.

By way of a final comment I think the question of large scale demolition of council homes is rather more complicated than is suggested here. One of the challenges of combating climate change is that of a “just transition”. There may well be significant amounts of embedded carbon in existing properties but if that becomes and excuse to trap tenants in unfit, unpopular and expensive to heat homes than there will be nothing “just” about the transition. There are still Council tenants in Scotland that want their homes demolished. Climate change is not a reason to force others to live in homes that you wouldn’t accept for yourself.