Shuggie’s Glasgow

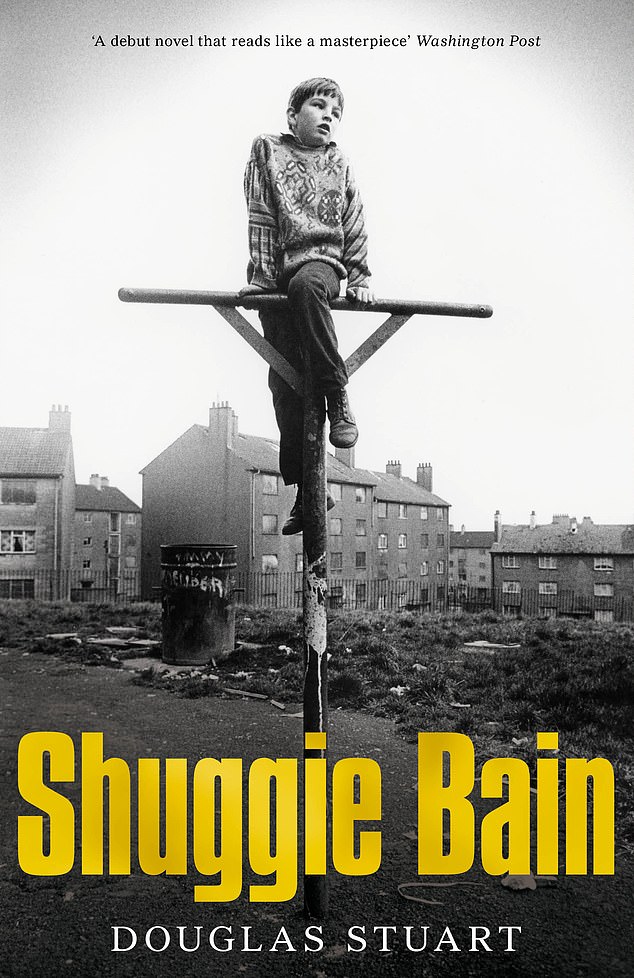

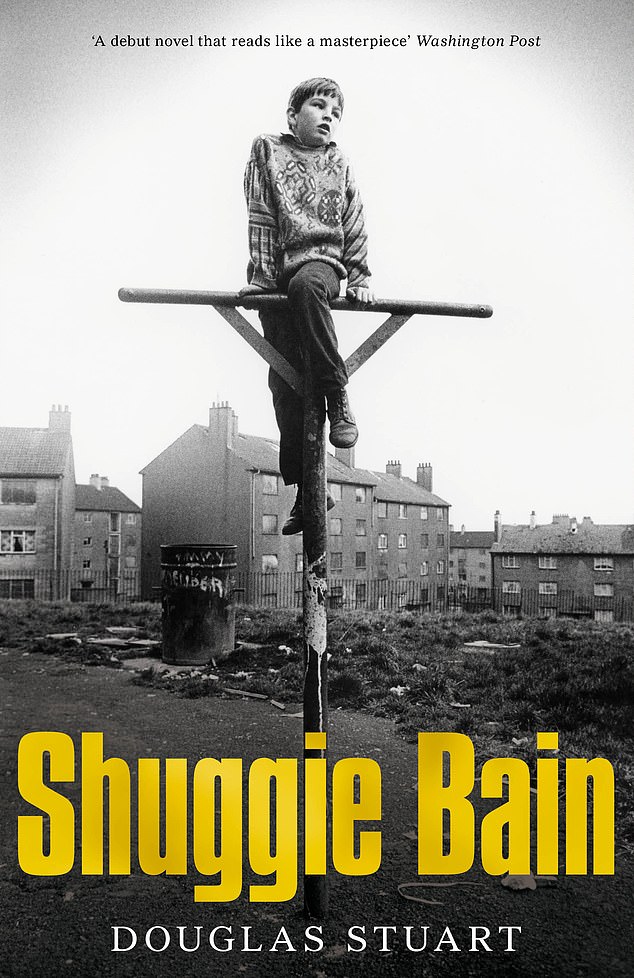

Before the hype, the Booker win, and the plaudits from the First Minister, Shuggie Bain was greeted ambivalently in Scotland. News of another novel about the grit and the glamour of the sick second city was met with audible groans. The title, the themes, the cover photograph, all played straight into a specific sub-genre of Scottish cringe. Scheme-cringe? Macho-cringe? Certainly a West of Scotland kind of eye roll. Paul McQuade tweeted to say ‘Challenge: Write anything set in Glasgow that isn’t about growing up in a scheme or alcoholism.’ Laura Waddell put it exactly right in the Scotsman when she said (in an otherwise positive review) that the book’s cover looks like it belongs in the ‘forlorn Scottish section in Glasgow Airport’s WH Smith, stocked with the miserable, outdated gangland pulp that makes contemporary Scottish publishers shudder.’

Now, as Scotland’s second ever Booker Prize winner, Shug is talked about in different terms, with words like ‘masterpiece’ deployed. It has undoubtedly won itself a place in the Glasgow canon, alongside books like The Dear Green Place, Lanark, How Late it Was How Late, and The Cutting Room. Shuggie Bain will shape how Glasgow is seen, and inevitably, how it chooses to see itself.

There’s no question that it is a great achievement. A view of Glasgow at once panoramic and claustrophobic; a moving portrayal not just of addiction, but of the desperate, enabling actions of those who love addicts, and who depend upon addicts for love. What lifts it above the tawdry miserablism of lesser accounts of the city is its narrator. Douglas Stuart gives us the gift of seeing a familiar Glasgow anew; showing it through the eyes of a queer child. We see the Clyde’s industrial decline, the brutal impact of Conservative rule, and the terrible violence of a city blighted by class war and sectarian hatred. But we see that world freed of any national or political context, instead depicted with the naivety and honesty of a child survivor. Machismo and oppression brutalises one small boy in the city, but he overcomes Glasgow’s drawn out deaths to tell us something deeply moving about resilience and love.

Personally I don’t agree with McQuade, I don’t think we have a surfeit of stories from the city’s schemes; though they may loom overlarge in stereotypes of Glasgow. But regardless, we surely had not yet heard the voices of Glasgow’s queer working class lifted up like this. Edwin Morgan called Glasgow the ‘bisexual capital of the universe’ and here we are given, perhaps for the first time, a gay Glaswegian bildungsroman, in which a child navigates homophobic and sexual violences as well as the streets.

But why, then, do I still sympathise with the novel’s detractors? There are frustrations with Shuggie Bain’s form, style and context which, as auto-fiction, it feels hard – even cruel – to criticise. At times though, even if it may be true to the author’s life, moments of unremitting grimness and violence skirt all too close to parody. The reader and characters are not given enough space before the next blow comes, and the book ends up feeling like a mash up of Jim Kelman and Angela’s Ashes; with us, the readers, cast as the Banter Boys from Chewin the Fat, enjoying the Glasgow Patter as we watch the horrorshow unfold. At its worst the book mines the cliches of misery memoir: art and artifice give way to the voyeuristic and cold. This feeling is at its most pronounced when the narrative moves away from Shuggie’s mother, Agnes. It’s there, removed from the warmth of Shuggie and Agnes’ relationship, that the book struggles. Yet the depth of feeling for its characters cannot be faulted, and any criticism must come with the caveat that this is a first novel.

Perhaps this conflicted review of the book comes from reading it in its own city; while finding it so wildly disconnected from its own cultural tradition. Maybe my view of the book is harsher sitting, as I am, two streets away from the tenement in which the novel opens. It is hard to imagine it as a book that anyone in Glasgow would have written, or published, it being so seemingly frozen in a conception of Glasgow from its own past. And maybe that is the book’s strength and its weakness. It is an intimate outsider’s view of the city. If Douglas Stuart had settled down in Germiston or Pollokshields, his whole context for his story would have been altered, his memories of that time would have become coloured by what followed them. But from across the Atlantic he is able to show us a Glasgow preserved in alcohol, coloured by his own experiences outwith the city. Who cares if we don’t always recognise it, or if we find it too grim or jarring. It is Shuggie’s Glasgow.

A fair review, I started the book but was overwhelmed with my prejudices towards ‘misery memoirs’ and Glasgow as the ‘No Mean City’ which I have always been chippy about. I would propose that to leave Glasgow and explain we are a city of the finest artists, musicians, academics, designers, and so on is still often met with a patronising smile and still considered to be ‘despite it being grim’. As a corporate lackie I know that the Glasgow accent is useful to impart a toughness and pseudo ‘straight talker’ vibe amongst the London mob. I will try and finish the book, but a book about Glasgow that is devoid of class seems impossible still ( tho i contradict myself as Lanark possibly manages it? I forget.) Is a true weegie still less than authentic if you were brought up in a bungalow and dont at least have a vague connection to some alcoholic hardman who had a heart of gold? My point is that Knausgaard(for example) isnt particularly working class he is just ‘nordic’ and therefore classless (at least to other scandinavians), the authenticity of his memoir is in the fastidious details of his life which are as complex, mundane and odd as anyone elses. I would re-work McQuades challenge that it is unlikely we could produce a Knausgaard in Glasgow so entrenched are we in class and suffering, alcohol and sectarianism, a suspicion of the middle class and their new money. The reason for this, I propose, is that your life wouldnt be considered ‘real’ if you hadnt risen from the grimy pit of a Glasgow tenement or whatever odd mixed mythology you have of your own childhood. And yes I will try and take my own silver spoon out my mouth when re-reading this book. ( which i am sure is authentic and true, just sayin’ ok big man?)

I don’t believe that James Kelman would write a sentence such as “a cloud of disappointment crossed Mr Darling’s face…”

All the reviews I have read deal with what the novel is about, not how the book is written…a sign of the times…

Three of my own books were set in Glasgow; none was primarily about living in a housing scheme (although I grew up in Drumchapel) or poverty.

However they were all published by Scottish publishers – the London lot didn’t want to know.

In the 1980s I had a contract from BBC Scotland to write a radio play. The producer said it was so good she’d offer it to London to see if they wanted to network it. She said even if they didn’t like it she’d put it on in Scotland

.

London didn’t like it. However they noted I lived in Glasgow and asked if I would like to offer them the draft of a radio play about unemployment.

After London rejecting the original play the Scottish producer lost confidence in it and said she wouldn’t put it on after all.

A very neat parable of our plight, Mary, your radio play which was never produced….

Did a cloud of disappointment cross your face too Mary when you got that rejection letter or did you maybe just frown?

But it is everywhere in the world of literature, this needlessly complex and overblown and often ornate use of language which is basically just gibberish. I mean look at the Washington Post quote on the cover: “a debut novel that reads like a masterpiece…”

I mean, that itself is a misnomer. What that line should read is “a debut novel that reads like a classic” which is what reviewers often say and would make sense because we, now, in the present, don’t know what will endure and so become a classic… hence, it merely reads like a classic (but we can’t be sure is one yet)

But the reviewer either believes the book is a masterpiece or not, it can’t read like a masterpiece, it is a masterpiece or it isnt….that’s the blurb on the front page of the Booker Prize winner…

Is there anyone in the UK writing complex novels which are intellectually challenging and make you even occasionally look up a word in the dictionary, like the ones they have in America, Thomas Pynchon or Don Delillo to keep it simple?

We don’t have anyone like that I can think of in the UK…

Well there’s me. I am an author writing at the height of my powers and the new John Le Carré

All was well in the end: I turned the original radio play (with a time-shifting para-psychological plot) into my first fiction novel “Everwinding Times” which got published by Argyll Publishing.

Of course poverty should have a voice, as long as the characters in a book aren’t mainly defined by their poverty but are given individual identities and lives. And as long as cities like Glasgow don’t get defined that way too – and are thus objectified by publishers and readers who have never visited Glasgow and would never dream of coming here.

I can’t comment on “Shuggie Bain” as I haven’t yet read it (though I plan to soon) . I’m very much in favour of writing in Scots (one of my books “Stirring the Dust” is partly in Weegie and partly in Doric). But in writing the Scots (including Glaswegian) standard spelling should be used as far as it exists. For example if you spell the word “wean” (derived from “wee ane” ) phonetically as “wain” you encourage the mistaken idea that it’s corrupted English – slang.

I’ll look out for your novel, Mary. Nothing is lost everything is transformed, as the old saying goes, eh?

I haven’t read “Shuggie Bain” either, I just read the first few pages on, eh, sorry, Amazon. Up to the cloud of disappointment, at which point I stopped. Though eventually I will read it. Anyway, it’s a pretty amazing achievement to win the Booker with your first novel. Or in fact at all.

Anyway, the novel has long ceased to be the site for the best prose writing in the language, as it used to be for centuries. I mean, if a body was learning English and wanted to read the best prose of our time, they would be better reading basically anything but the novel: history, the social sciences, philosophy, maybe popular science, but not the novel. The novel is the place where sloppy writing is not only tolerated but encouraged even. It’s all William Faulkner’s fault arguably.

There are exceptions: Bernard MacLaverty for example…but in general, sloppy writing, ornate and overwrought language, an indiscriminate use of metaphor no matter how trivial the incident described, hackneyed prose and incessant cliche are all found in probably most novels published these days….

The novel has become a place where people come to offload…like one of these infernal Saturday night talk shows featuring troubled minor celebrities with addiction problems which flourish in Mediterranean countries….

Anyway, why mix up William Fauulkner in all of this? Faulkner made a virtue out of one those features which alas in our times are seen as a vice: difficulty. His at times opaque texts are pleasingly opaque, like the first half of “The Sound and the Fury” which is opaque and difficult but which still is bewitching and captivating and totally engrossing so that when you finish it you want to go back and read it again, immediately, no sooner than finishing the darned book. Or the seemingly effortless inventiveness of Nabokov, the sheer artifice of that literary world of his, the pinpoint precision of his language, the ever present irony which is always twitching at his pen….alas, it is hard to imagine either Faulkner or Nabokov being even considered for the Booker prize…

The writer in English who I feel is still minting every single line fresh for the world is MacLaverty, who also has the gift of metaphor, which is the great poetic gift, and irony, which is a kind of balance to that….but I don’t read a lot of contemporary fiction these days…

The Glasgow in the book still exists. It exists in Pollok and other areas of the city. Sure, it has become gentrified in part but we cannot deny the existence of poverty, addiction and hate that persist here. The book is a difficult and at times brutal read. It is also, at times, moving and sad. It isn’t a parady of a city but a reflection of a childhood spent full of angst and worry. It is about a boy trying to come to terms with his sexuality amidst the chaos and uncertainty brought about by his father’s ambivilance and his mother’s self destruction. The author isn’t James Kelman but he gives an honest account of childhood and is to be admired for a nievety that allows us a glance into his desperate childhood.

We were also there in our thousands. In Knightswood, Scotstoun, Mosspark, Riddrie – in excellent council houses with front and back doors and carefully tended gardens. All of our social lives revolved around church or chapel – youth clubs, badminton, drama groups – and our parents never crossed the door of a pub. Many of us attended one of the half dozen Glasgow Corporation selective schools – Allan Glens, Hillhead, St. Aloysius, Notre Dame, Boys’ High, Girls’ High – where our aspiring parents paid fees of £3-9-0 a term.

Boring? Maybe – but we were also part of the Glasgow Story. The invisible part.

“No Mean City” ya Bass! N.M.C. is, first-and-foremost, an effortless masterpiece in sociological observation, a journalistic depiction of a Glasgow (with necessary but minimal and obvious licence) that actually existed. Well worth a reappraisal on its own merits, in my, non-literary, opinion. Douglas Stuart, if only by broaching the subject of his protagonist’s sexuality amidst the usual furniture of the Glasgow read, has created a space all of his own and has absolutely nothing in common, apart from location, with A. McArthur and H. Kingsley Long, of “No Mean City” ‘ infamy’.