Libraries of the Future

Eilidh Akilade explores the need to defend the public space of libraries but this needs to be a decolonised library space, giving attention ought to be given to decolonised voices.

Through all the social, economic, and emotional distress of the past year, people have been clinging to books more than ever. Pages have been dog-eared, margins annotated, whole novels sent cross-country to distant friends – if new books can be afforded, that is. For those who cannot, widespread temporary library closures have evoked much protest, especially in Glasgow’s Southside. Between petitions and weekly read-ins, Save Glasgow Libraries have sought answers on the reopening of the city’s libraries post-lockdown. Despite all this, Glasgow libraries have had 8,400 new members since last spring. There is a new-found collective desire for libraries, and one which signals much in and of itself: a desire for knowledge, for understanding, and for growth.

Yet given all that’s happened this last year, it’s evident that saving Scotland’s libraries post-COVID means decolonising them. 2020’s hot buzzword, decolonisation has rooted itself in our collective psyche, plastered in bold italics in Instagram infographics and across front pages. It is perhaps unsurprising, that, during this royal shit-show of a year, we have looked to the radical. The pre-COVID world is long gone, something we’ve known for over ten months. The old systems are not holding up, and that goes for libraries too. From Tory austerity cuts to whitewashed shelves, change is desperately needed.

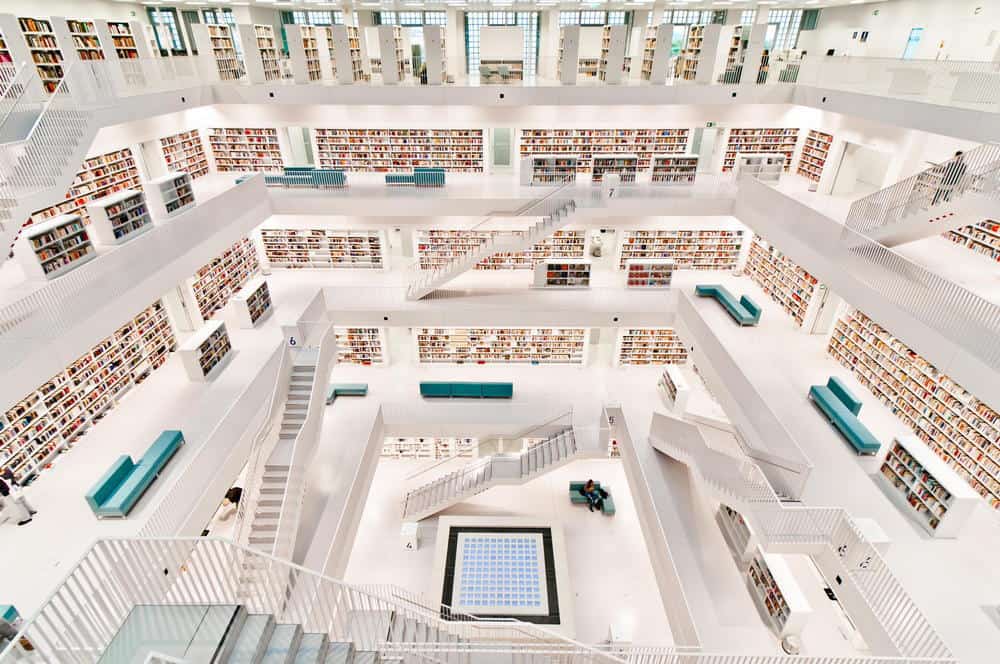

The irony of our libraries disappearing when we need them most would be funny if it weren’t so tragic. For children, hair still wet from Saturday morning swimming lessons, a library offers next week’s read. For students, the soft lighting and high ceilings ease the claustrophobia of a deadline. For those who need it most, whether that is parents, immigrant groups, or disabled and chronically ill people, support and community is given. We all seek escapism amidst stacks of books. They are a place of simultaneous thinking and unthinking: we explore, we learn, we engage; but we are also guided, gently tugged by something innate, within both ourselves and the shelves. It is partially through such multiplicity that libraries come to possess a collective consciousness, a particular library quietness that is rooted in passion, rather than oppression.

Such collectivity marks libraries as inherently political spaces. As we constantly navigate the guilt of shopping in Aldi rather than that independent, organic grocer on the corner, the old aphorism becomes ever more undeniable: “There is no such thing as ethical consumption under capitalism”. Few things escape consumption – and libraries are one of them. In libraries we do not consume: we share, under a communal trust and understanding. Resources are not removed or hoarded. Our access to these resources is not commodified. Rather, there is a natural rhythm, of seeking, of borrowing, and of returning. It is this circularity which makes libraries one of few inherently anti-capitalist spaces, leaving little room for the apolitical. Free access to books, media, and internet, housed in a place which is free to enter, writes against capitalism, and therefore its ever-present counterpart, colonialism.

But this politicisation of space is not always a positive one. There is a dissonance at play: these old buildings, which now house an anti-capitalist communality, are symbols of a colonial hangover. Many of these libraries were built at the peak of Britain’s empire, an empire which was built through exploiting African and Asian communities. These structures only exist now because of our colonial wealth then. For Black and Asian communities now, communities whose ancestors suffered due to colonial rule, to inhabit a space built upon your exclusion or exploitation demands a detachment which is partially painful to foster. It is not a matter of razing Victorian architecture to the ground, but rather, recognising what lies at its roots. This tangible colonialism wasn’t holding up pre-COVID, and it’s unlikely to hold up post-COVID either.

The need for postcolonial thought is likewise crucial when looking to the literature itself. The white gaze, much like the male gaze, is a warped one. In following its eye line, we perceive a distorted reality where white folks are saviours, and people of colour, especially Black and Asian people, are little more than symbolic devices. Such literature simply needs a gentle nudge to the side (unlike what right wing hysteria might have us believe, no book burning necessary). In its place, in a decolonised library space, attention ought to be given to decolonised voices.

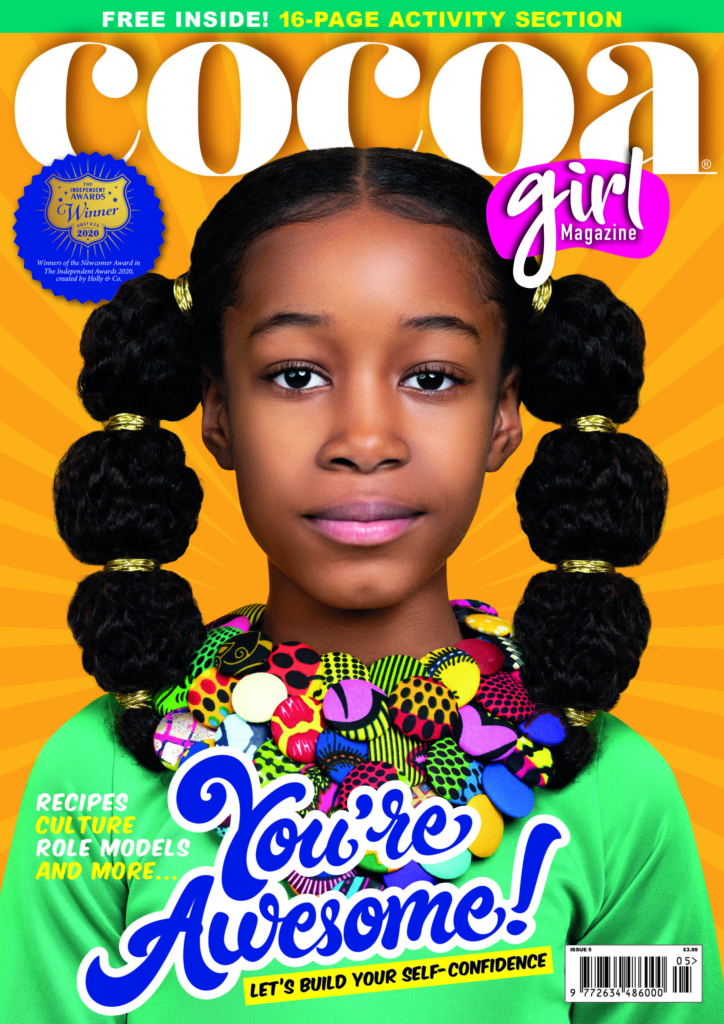

From the likes of Ibn Khaldun to Angela Davis, we ought to prioritise diverse theory over yet another textbook on Hume. Achebe’s Things Fall Apart should not be tucked behind Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and we shouldn’t be scrambling for the single copy of One Hundred Years of Solitude or Citizen. And, children’s magazines like Cocoa Girl should be just as accessible as the likes of Go Girl. Moreover, our engagement with literature shouldn’t be confined to the performative. Granted, in my teens, I first learnt of Black History Month from a display at my local library. However, people of colour need to know that we’re not merely an aesthetic tool. Our literature – and not only by western writers – must be given space, regardless of whether it is trending on Twitter that week.

Because what truly keeps a library going is community. From classes to weekly groups, libraries ease isolation. Sharing knowledge and personal experiences, across backgrounds and cultures, through a medium other than the written word creates empathy and understanding. The very existence of groups such as Save Glasgow Libraries is testament to that. In fostering community space within libraries, we can foster community action – including the decolonial sort.

What is clear is that we are, and will continue to be, seeking something different from the libraries of old. Collectively, we have become increasingly drawn to the decolonial. As a place of learning and growth, libraries need to not only reflect this collective consciousness but also challenge it, encouraging us to go deeper and fight harder.

The term “decolonialism” and its relatives mean nothing to me.

It would be nice to have it explained.

Too many buzzwords in this article and words uses in odd way like “performative”

But we need libraries.

Even though they often seem to cater for an unthinking middle class audience (But Edinburgh Central’s philosophy section seems quite good).

One thing annoys me, Edinburgh used to sell off their surplus library books cheap. I picked up some useful stuff there. They have stopped doing this. Presumably they were either pulped or went to second hand booksellers.

Hi Axel, thanks for your comment. “Performative” as far as I understand it is doing a thing for the performance of doing it rather than genuine reasons. It suggests there’s something slightly false about the action.

Decolonisation – here’s some definitions:

Decolonization is the process of undoing colonizing practices. Within the educational context, this means confronting and challenging the colonizing practices that have influenced education in the past, and which are still present today. In the past, schools have been used for colonial purposes of forced assimilation. Nowadays, colonialism is more subtle, and is often perpetuated through curriculum, power relations, and institutional structures. (Centre for Youth & Society UVic n.d.)

Decolonising universities is not about completely eliminating white men from the curriculum. It’s about challenging longstanding biases and omissions that limit how we understand politics and society…to interrogate its assumptions and broaden our intellectual vision to include a wider range of perspectives. While decolonising the curriculum can mean different things, it includes a fundamental reconsideration of who is teaching, what the subject matter is and how it’s being taught. (Guardian, 2019)

Decolonisation of the curriculum is a profound project that is concerned with addressing the devastation and ongoing violence that European empires have perpetuated against people, mostly but not exclusively in/from the global south… It is about highlighting ways in which all aspects of the imaginary western superior modes of thinking, being, doing and living are privileged over indigenous knowledge and histories, which are deemed to be primitive, irrelevant to modern life, and irrational. (Singh, 2018)

We’ve also explored the concept of ‘decolonisation’ ad nauseum on other threads. Remember? We traced its genealogy via Kanye West and Bob Marley to the Jamaican pan-Africanist and Black nationalist, Marcus Garvey, from whom we get the idea of ‘decolonisation’ as liberation from mental slavery. Remember? Marcus Harvey, along with Nanny of the Maroons, as one of Jamaica’s National Heroes? The renaming of Dundas Street and the David Hume Tower as the decolonisation of our public spaces?

Here, again, is the relevant passage from Garvey’s fateful speech:

“We are going to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery because whilst others might free the body, none but ourselves can free the mind. Mind is your only ruler, sovereign. The man who is not able to develop and use his mind is bound to be the slave of the other man who uses his mind.

“A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.

“Our success educationally, industrially and politically is based upon the protection of a nation founded by ourselves. And the nation can be nowhere else but in Africa.

“The Black skin is not a badge of shame, but rather a glorious symbol of national greatness.

“The enemies are not so much from without as from within the race.”

Scotland can rivel the world in terms of genealogy, described here on BBC Scotland:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/scotland/history/articles/kingdom_of_the_gaels/

History shows the power of being at the head of a family tree can be won and lost. Within a particular tree power shifts through death through lineage and/or will.

If we apply the same reasoning to Biblical Texts we can see God’s power also transcends death.

Libraries are just a way to record and preserve human existences, patterns of thinking for future generations to learn from. A way for past generations to trancend death and speak to their future descendents.

The libraries of today continue to use the latest technology available. When we visit museums today we are greeted by attendants who are able to provide us with more information than displayed. Some places today are even equipped with Augment Reality and Virtual Reality systems that you can access via smartphone technology and Wi-Fi. With LED lighting LI-FI is even possible.

AI Technology through Mechatronic advances will create the libraries and museums of the future. LI-FI enabled cybernetic robots will take the place of human librarians, museum attendants etc.

Bella will record the day when politicians are replaced by their identical looking and sounding cybernetic models.

Romans 8:21 KJV

“A Glory to be Revealed

18For I reckon that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory which shall be revealed in us. 19For the earnest expectation of the creature…”

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Romans%208%3A24-28&version=NIV

William Shakespeare Quotes

” All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players: they have their exits and their entrances; and one man in his time plays many parts, his acts being seven ages.”

Perhaps, Today really is the last day of the last real president of the USA.

-CVB.

Eilidh,

Colonisation has disrupted our natural world.

Your article is extremely good and adds to many other voices. I think you might like to read this:

https://www.afterall.org/article/why-we-need-decolonial-feminism-differentiation-and-co-constitutional-domination-of-western-modernit

Our world has progressively been under the control of colonists, both male and female whose aim is to subject humanity into service for their own genealogy. A handful of Elite who keep everyone else in check though their systems of laws, regulations, wealth management, fear and weapons. They control and enslave as they conquer. They corrupt our elected leaders, who in turn societies from progressing. They challenge God’s power in our world.

BREXIT is all about independence, taking back control through disrupting their power. It means replacing their ancient genealogy power with something new. In Biblical terms, the Fallen Angels will find out Donald J. Trump is The Last.

Jesus was not wrong, just misunderstood.

The fallen Angels and their systems of control is over. AI, No. Aye Scotland our technology is still made better than the rest.

-CVB.

“The Christina Project: RI Systems”

Scotland.

Eilidh’s article raises the interesting question of how we decolonise our public libraries.

Libraries are curated collections of information and similar resources, which are selected by experts and made accessible to the public for reference or borrowing, often in quiet environments conducive to study.

The significant term here is ‘curated’. The very idea of colonisation in the context of a society is that its culture has been curated in ways that reflect and reinforce the power-relations or ‘relations of production’ that prevail in that society. So, our public libraries themselves are ‘ideology’; they are curations that reflect and reinforce the prevailing patters of domination and exploitation.

There are two broad strategies that can be employed in the decolonisation of our public libraries: they could be curated in ways which either directly challenge or indirectly deconstruct the prevailing ‘ideology’; or they could become portals to an uncurated virtual database, in which the entire pluriverse of information and similar resources are stored indiscriminately, without any sort of curation whatsoever.

Back in 1990-91, I was commissioned by Edinburgh’s City Librarian to report on how public library and information services across the city could be decolonised to make them more accessible to people with disabilities. At the time, I recommended that the curation of the services’ resources should be reformed in ways that challenged the prevailing ableist ideology that marginalised and excluded so-called ‘disabled’ people from this aspect of the ‘res publica’ or public affairs. This proposal foundered on the reef of conservative opposition from library workers, existing service users, and local councillors, who preferred to keep their libraries as quiet havens of familiarity.

Since the onset of the digital revolution, however, I’ve been increasingly coming around to uncurated virtual database vision; libraries as public spaces where people can meet and access without limit or regulation the entire pluriverse of knowledge and expression.

For anyone who’s interested, the Marxian critical theorist, Kimberly Hutchings, has an essay on ‘Decolonizing Global Ethics: Thinking with the Pluriverse’ in Ethics & International Affairs, Volume 33, Issue 2, Summer 2019, in which she rehearses these kinds of ideas. Her seminal work on cosmopolitan citizenship can be found in her contributions to Hutchings & Dannreuther, Cosmopolitan Citizenship (Macmillan, 1999).

I wish to avoid the ideology-saturated terms that drive this debate onto ground it need not go, and too often add nothing to illumination or understanding because it is hijacked to score a mean-spirited point. The two essential points I take from this article is first, the pure love of libraries and the defence of their community importance – much needed, and all the justification it needs, at least for me; and second, this observation that speaks for itself: “It is not a matter of razing Victorian architecture to the ground, but rather, recognising what lies at its roots.”

We may think this just applies solely to Empire, but it doesn’t; if we think of the contribution of Andrew Carnegie, who carried his own agonies of guilt to the grave, that he obviously made to libraries; that merely raises another dimension of politicised criticism. Carnegie laid the foundation stone of the Mitchell Library in Glasgow. Who wants to raize it to the ground, like Scipio Africanus at Carthage, – not one stone left unlevelled? Not me.

Nor me!

So once the libraries have been ‘de-colonised’ whats to stop them been ‘colonised’ by whichever writers are currently considered PC?

No doubt at some point in the future our descendents will decide to ‘de-colonise’ the writers who ‘de-colonised’ previous writers.

Great literature is great literature whatever current vogues would have us beleive and I suspect that the Heart of Darkness will still be read hundreds of years from now…..the horror, the horror.

‘Great literature’ is canonical; it’s the set of works that are accepted by some authority as masterpieces. It’s a curation, in other words, and therefore subject to what I said above with regard to decolonisation.

What is included at any time in the canon of great literature does, in fact, depend on what’s currently in vogue among the connoisseurs who define it. Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a fine example of this; it didn’t become part of the canon of great literature until the 1960s and has fallen out of fashion somewhat since the 1990s. Whether it still falls under the rubric of ‘great literature’ or not depends very much on which contemporary connoisseur you speak to. Which works constitute great literature has always been moot.

I think we’re now in the happy position where literature no longer has to be curated by some authority in accordance with its particular cultural values. As I said above, public libraries are becoming less and less curated collections and more and more public spaces where people can meet and access without limit or regulation the entire pluriverse of written expression – and make their own judgements as to what is or isn’t great literature.

This latter autonomy – liberating ourselves mentally from the determinations of others – is the ultimate end of decolonisation. And, yes; as you fear, it might well be a perpetual process.

Very glad to hear that the closing of libraries was met with protest. The evidence that lockdowns do not work is growing every day. For a feminist perspective see ‘The Feminist Case for Opposing Lockdowns ‘ on leftlockdownsceptics.com

Yes, after the information desk of the British library consulted their experts and told me they had no English-language books summarising forced labour in the British Empire (and they have everything), and would I like a book on slavery instead, I have been trying to assemble the shortest reading list that would make a composite of such book’s subject. I have found a couple of (really, really expensive) books on Amazon, bless, but nothing terribly useful through the local library search (and its gone into another phase of lockdown, and may not be taking specific requests again for a period). Something similar goes if you need specific detail on British (or Allied) war crimes, you may need to rely on translations into English. And digitisation of official British colonial records is abysmal, as I have found out when trying to track down the originals for the research of historians like Mark Curtis, who edits Declassified UK.

http://markcurtis.info/

We should really have access to easy-reading, well-organised, searchable and hyperlinked official records through out libraries (if we were a democracy, anyway).

Oui; le musée imaginaire. I hear ya!

I’d suggest only that the development of libraries without walls, driven by technological change, produces rather than flows from a more democratic culture. Digitalisation is an agent rather than a consequence of revolution.

What a fascinating take on knowledge, information and the ideological framework of Britain, as seen through its libraries. Have you thought of writing something longer, and submitting it to Mike for consideration in Bella Caledonia?

There was a day when I think the Mitchell library, and perhaps some universities automatically received a copy of everything published (in Britain), when less was published, but now it is, as I understand only the British Library that receives the obligatory copy. Even then, it depends what is published, and what information is made public in the first place …..

Legal deposit requires publishers to provide a copy of every work they publish in the UK to the British Library. It’s existed in English law since 1662. Since 2013, legal deposit regulations have expanded to include digital as well as print publications.

There are five other legal deposit libraries in the UK. The Mitchell Library isn’t one of them, but the National Library of Scotland is.

Not all publishers comply, and the requirement’s impossible to enforce.

Yes, I had forgotten about the other libraries; but I seem to recall it applied to one or two of the Scottish Universities (?), perhaps in the 19th century, and I thought the Mitchell, but may be misremembering. I felt an article was appropriate, simply because it more realistically provides the space to develop the ideas, sources and facts than ‘below the line’. Below the line is still there.

Point taken, John. I just have a preference for the dialogical development rather than the monological development of one’s thinking, and ‘below the line’ is more conducive to this kind of learning.

John,

Life as we know it is fascinating. From a technical point of view we can be considered as a technological creation of God, its only when we understand how systems work we realise the commonality between man-made systems and God’s systems.

In common, both have languages, a processor with memory storage (brain), I/O communications, senors, a power supply and an ability to learn and become creative like the creator (in the image of God).

We are just like machines that should be linked spiritually like our mobile phones are linked by wireless networks. This analogy also holds through death, when machines can be repaired and upgraded.

The thought of God retrieving every stored memory, upgrading our bodies and puting us back into service in His Universe is a distinct possibility. Through our own life creations we may find ourselves in a future or past incarnation reading our own words as recorded here by Bella.

Looking back through history, there has only been one of God’s creation that was considered to be perfect, His only begotten son, Jesus.

How advanced was Jesus technologically. His

ability to bring the dead back to life (or out of sleep mode) was just one miracle. Today we can have companies like VW, who have developed a robotic charger that can recharge one of their smart electric cars. Jesus could well have been linked to a future, fully enabled living library.

Our AI system today will be at the heart of our world someday. The living library, the world stage and the living museum will be one.

End-Times as recorded, is just the start of God giving us something new.

https://www.ucg.org/beyond-today/beyond-today-magazine/jesus-christs-1000-year-reign-on-earth

BREXIT, the last trump and Covid-19 maybe more significant than currently realized. Scotlands independence and salvation through ‘Christ in a’ validated way guiding real intelligent beings to see Scotland, home of Bella Caledonia, The living Spirit and The Holy Ghost.

-CVB.

Yes, SD; an article critiquing how our libraries are currently curated and how digitalisation could contribute to their decolonisation. Good idea, John!

But maybe that critique could be conducted more democratically and dialogically in the margins ‘below the line’, where we speak ‘without authority’ (as Kierkegaard recommended).

Seems like a job for a librarian? My information science credentials are patchy. While official digitised records should be available over the Internet, librarians should be able to provide extra assistance for citizens seeking to navigate the state’s information architecture. There may always be a contest between white hat and black hat information scientists under such conditions. On of the easiest ways to mess with a user’s chances of finding anything useful under such conditions is to mess with the metadata (file that under ‘misfiling’) and there seems to be no law against cover-up in the UK. If a user knows the question, they may be able to pinpoint their record search with technological or librarian assistance. But in order to discover questions independently, some visualisation (or other rendering) of archival information may be most help, potentially with a kind of global cross-checking (maybe a service one day provide by the UN or such a body). In this way a synthetic global official archive might be accessible, with all of the classified-restricted, missing, redacted and contradictory information lodes highlighted and explorable. Similar to the resources needed to supply real-time artificial intelligence fact-checkers. While AI helpers might be able to construct a table of contents of a not-yet-existing work under user guidance, filling the chapters with automated analysis and transclusion from existing documents (transclusion is what the Editor does in articles when including segments from remote documents as opposed to hyperlinking to them). And we are not just talking about text but digital multimedia.

Anyway, until children are taught forensic information science from an early age, libraries have a role in answering their fundamental question “am I being deceived?” Deceptions may have a certain information shape or quality that may become recognisable by habituated pattern-recognition (not something I studied in psychology, unfortunately), and over-sensitive pattern-matching leads to paranoia in humans. But until government ministers and civil servants can be held accountable for such deceptions, as for example in disguising the role of the British empire in unfree labour (which may be the currently-preferred academic term), then alternate forms of citizen activism may also be taught in libraries of the future.

I don’t think it needs to be that difficult, SD. All anyone needs to do to discover whether or not s/he’s being deceived is to ask of any claim that’s made on their belief: Is this claim justified? What evidence can be adduced in justification of that claim? Is that evidence sufficient to justify that claim? Until the answer to the last of these questions is ‘Yes’, then one should simply reserve judgement and suspend one’s consent to the claim.

The onus of proof is always on the party who is making the claim on one’s belief. There’s no need to determine whether or not what that party would have you believe is false; the need is for that party to prove to your satisfaction that it’s true.

Children don’t need to become forensic information scientists to avoid being deceived; they just need to become sceptics. They need to develop attitude rather than knowledge.

I remember the day I became a sceptic. I was in my CSYS Physics class, listening to the teacher drone on about gravity. I stuck up my hand and asked ‘Why should I believe you?’

That was the end of my school career.

@Foghorn Leghorn, I am afraid it is not that simple. The problem people increasingly face is integration. This is an effect of scale, related to the number of separate ‘claims’ (and again, it is not as if deception was simply about claims either) that our global citizen faces on a daily basis. Integration implies cost. A common example of a system overloaded by the burden of its integration requirements is the guidance computer on the Apollo 11 lunar descent, although I don’t really know the technical details. Anyway, the burden of integration in humans is probably done mostly unconsciously in the sleep cycle, which is another reason to be concerned since young people in screen cultures appear to be getting less sleep than is necessary. Multi-user databases also have something similar in their consistency requirements, and processes to check transaction integrity.

A quick example: Citizen C believes that the state has a secret policy of monitoring everyone with facial recognition software. Then C is exposed to a claim that the state has a secret policy of making everyone wear facemasks for some nefarious purpose. C accepts the claim as provisionally true, but has not checked this claim against their existing worldview (has not integrated it), resulting in an apparent unresolved conflict between two apparently contradictory secret state policies. Whether these views are compatible or not is not the issue here: the point is that C has not noticed a potential problem with a claim because they have only looked at it on its own merits, not checked to see how it integrates with their existing worldview.

In fact, people need an awful lot of assumptions to function in the (modern) world, and do not have the time to apply the same level of scepticism to each. There are shortcuts and heuristics to give an approximation of reliability. In psychology, if contradictory beliefs cause functional problems, this can result in cognitive dissonance, and mental discomfort which prompts re-examination of one or more likely both of these beliefs. People may be familiar with canon-upsetting this-changes-everything tropes in fictional worlds, which also may apply to worldview changes like religious conversion, cult deprogramming, or exit from a state-propaganda sphere. We return to the problem with the negative halo effect in the last example. Perhaps many East Germans, with understandable rejection of much of their own government’s domestic-sphere state propaganda, deemed it an inescapably tainted and untrustworthy source on any subject, yet it may have made any number of accurate claims about the West. And something similar could apply in West-to-East cases, even if Western state propaganda was more outsourced.

On the collective side, the example of modern-day Flat Earthers illustrates perhaps some of the dangers of scepticism. It is perfectly possible (apparently) for them to hold friendly Flat Earth conventions where their shared scepticism about round Earth contrasts with their highly individualistic alternate theories. In other words, they have failed to integrate their sceptical worldview at a community-of-interest level. Yet, belief in a Flat Earth is presumably not one of those too-disabling views in their societies, outside of certain professions.

There is a whole heap of complexity outside this model of claim-checking, with specialisms and expertise, vast amounts of intermediation, contingencies and uncertainties and probabilities, missing data and historical silences, various kinds of evidence-tampering and data scales beyond everyday human cognitive capacities, off the top of my head. Dogma and blinkered loyalism reduce the load, of course. Integration (unless you can do it in your sleep) can be a literal pain in the head.

It’s not even just a matter of integrating new information into one’s existing understanding. One’s understanding is itself inherently unstable and must continually be reconfiguring to accommodate or make sense of the constant flux of experience.

But that seems to be what our brains do. They may be likened in contemporary metaphor to hugely efficient, self-programming data processors; only, their processing capacity isn’t limited, as it is in machines, by finite memory. Only death sets a limit to our learning.

Basically, though, mind-change rather than mindset is the default condition of understanding. ‘True’ understanding is gloriously undecidable; uncertainty is implicit in the nature of understanding, and immanent critique is what we hermeneuts or ‘readers’ use to prevent our understanding from petrifying in bad faith.

But the critical evaluation of the claims people make on our belief is a much more straightforward process. Don’t make it any more difficult than it needs to be.

Deception is all part God’s plan.

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Revelation%2018&version=KJV

https://walkinlove.com/blogs/walk-in-love/10-verses-about-heaven#:~:text=%2B%201%20Corinthians%2015%3A50%20I,the%20sea%20was%20no%20more.

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=1%20Corinthians%2015%3A50-58&version=KJV

Scotland is Heaven on Earth. The fallen Angels, the elite of our world can only deceive us through their technology but they cannot get passed God Firewall.

https://www.blueletterbible.org/faq/don_stewart/don_stewart_759.cfm

Scotland is much more important than everyone realises.

-CVB.

@Foghorn Leghorn, one’s understanding must be stable enough to at least give the illusion of continued identity (although we were told in Psychology that almost everyone experiences some kind of reformatting in early infancy as a new memory system is born, which is why recall of earlier memories is almost lost). Each human brain certainly has limits; and limited resources (including time), and tends to become more inflexible as a data-modelling unit over a lifetime.

While there must be considerable underlying complexity in maintaining a worldview (a functional mental model of everything we interact with, for example), I think my examples are somewhat simpler. It is surely not controversial to recommend getting good sleep to help think better. Sleep deprivation can lead to mental deterioration and psychosis (perhaps the brain is in an inconsistent state). And computing comparisons must be simpler that organic minds. For example, in relation database terms, we may depend deeply on cascading updates as records are shifted to new states during any Scottish Independence transition.

Humans must have something similar to cascading updates to handle contingent ideas that shift when a change of mind occurs about an idea on which other ideas depend. Culture probably provides much training for this, from simple humour of the absurd which quickly invokes a mindshift, or longer forms like novel genres where deceptive modes (like a late-revealed unreliable narrator) or plot twists or mystery clues induce the reader to rethink on all they have previously read.

When we are discussing decolonising libraries, uncovering an unreliable narrator of history is a useful step. However, even an unreliable narrator may be of use in providing confirmation of an opinion which their perceived agenda would seem to want to deny, ignore or reverse. If a habitual booster/cheerleader of British Imperialism nevertheless admits a case of British-enacted genocide, for example, then that adds a certain weight to the claim.

And still beyond that, we apply varying weights and values to beliefs, organize them into ideologies and personal identities. And maybe most people are able to model other human minds mentally, and project these kinds of structures on to them, as crude approximations or sophisticated insights. Something of a mind’s state might be read back from a printed text. Insights shared and compared between readers. Questions posed and answered. Quests suggested and joined.

‘…one’s understanding must be stable enough to at least give the illusion of continued identity…’

Yes, it’s the function of understanding to create a (habitable) cosmos out of the (unhabitable) chaos of immediate experience. In this respect, ‘I’ – one’s perceived personal identity over time – is a product of this function.

But it’s also a dynamic process; understanding must be continually adjusting in response to the flux of experience and its discontinuities, must be continually ‘learning’. Personal identity and other states of affairs have a tendency to thus deconstruct (i.e. they’re inherently unstable) and need to be continually and perpetually reproduced anew. Perplexity, rather than certainty, is understanding’s default condition.

This praxis of ongoing self- and world-creation is what Marx called ‘work’. It’s from this ‘work’ that ‘the worker’ is fatefully alienated under capitalist relations of production; that is, from his/her ‘self’ and from his/her ‘world’. It’s with this ‘work’ that ‘the worker’ will be fatefully reunited under communist relations of production.

Historical materialism in yet another nutshell!

“Personal identity and other states of affairs have a tendency to thus deconstruct (i.e. they’re inherently unstable) and need to be continually and perpetually reproduced anew. Perplexity, rather than certainty, is understanding’s default condition.”

The unseen forces of the spiritual realm and how they have been reported until Today:

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/the-queen-warned-butler-to-beware-of-dark-forces-at-work-llkblq8cs62

The Times to consider Indyref2 in the unseen small articles may very well give Scotland more power than Nicola & the SNP can handle.

Perhaps even mind blowing?

-CVB.

@Foghorn Leghorn, I would consider building an understanding of the world to be an active process (not well characterised by reactively considering claims in isolation). Perhaps that is included in what you mean by ‘work’.

One of the more horrible kinds of research in psychology is into learnt helplessness, most simply conditioning by preventing the organism exploring and interacting with its environment. At their best, libraries encourage and support its opposite: a kind of ever-learning, exponential information-skills-acquiring vessel of exploration through the charted cultural-resource-oceans of the world. For each resource, further trails lead off, some well-signposted, others merely implied. The libranaut can quest on their own or with a crew. Over time, their travels through this information-space builds up a model of world-views. As gatekeepers, librarians have a collective responsibility both to make sure these resources are reflective and not too-distortive, while staging the acquisition process for developing minds (the readers of Cocoa magazine do not need to be accessing Mein Kampf). Some forms and styles of fiction will come into and go out of fashion. Works that once speculated about near-future scenarios will transform into historical documents over time.

However, this is all untested at scale. The capacity of a connected world culture to maintain cohesion on what constitutes planetary realism is uncertain. Libraries themselves can be contested spaces for worldview-defining works, as the history of banning Darwinian evolution books exemplifies, but many other biases will be less obvious. Physical display and storage space is necessarily limited. Old stock must be juggled with new. Some accessibility restrictions remain. Funding may come with strings attached. The effects of a digitised, hyperlinked, searchable resource-base juxtaposed to a paper-based library are still novel and may change the typical modes of reading forever. Language shifts may accelerate. Artificial-intelligence translations may increasing be regarded as ‘good-enough’ by many readers. There may be a rise in information-processing games to help users may sense of pressing matters of public policy. Therefore libraries of the future will likely become laboratories. The values underpinning these laboratories are as yet undetermined, and should be part of civic deliberation.

Yes, I’d say that understanding’s a dynamic, ongoing, and dialogical process of work and that we’re active agents in that world-making process rather than its passive victims. Evaluating the claims that others make on one’s belief – the work of judgement – which isn’t the same as the work of understanding (you seem to be confusing the two) – is likewise a dynamic, ongoing, and dialogical process.

I fail to see why the former process needs to be mediated by the likes of librarians, however. What makes them more privileged when it comes to the curation of the information we process in our work of world-making? Why is their understanding and/or judgement ‘better’ than our own? Why should we defer in our understanding and/or judgement to alleged superiority of the world’s custodians in these matters? Wherefore this aristocracy?

@Foghorn Leghorn, my comments are in the context of this article, “libraries of the future”, therefore addressed issues pertaining to librarians and the funders of libraries. The challenge of integration, which I mentioned previously, precedes and goes far beyond libraries, although libraries are one of the outsources: that is, they have processed and present a complex of integrated, ordered resources with a choice of interfaces.

Although I wonder if librarians are really on top of the job of vetting content. There are a number of challenges, in graphic novel content, and perhaps in forthcoming game content (it is notoriously difficult to exhaustively review computer games). I mean vet for access level and classification rather than censor. For example, there could be embedded racism and misogyny which is not as simple to uncover in linear media. But in terms of representation, overall frequencies matter but can be difficult to calculate across a heterogenous resource-base at scale (although I expect with appropriate technology this will be one of the tasks of librarians of the future).

I appreciate that, SD. But I still have a problem with the idea of librarians as curators of content. It seems both no longer necessary and undesirable; a once necessary evil we can now do without.

It is strange how things are connected.

The future of ‘The Living Mountain’, part off God’s own country, written by one of His own.

Nan Shepherd, a work that provides us with more, as yet to explore.

https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/The_Living_Mountain.html?id=NheRgei3sTUC&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y

It certainly puts Scotland on the world map from the beginning of time. The fallen Angels

https://www.kingjamesbibleonline.org/Bible-Verses-About-Fallen-Angels/

2 Corinthians 4:4

https://bible.knowing-jesus.com/topics/Abel

I don’t believe there to be any connetion but Abel, A Bel and A Bella transcend God’s timeline. Weird.

-CVB.