8 More Bricks in The Wall

The proposal to extend the school week does not consider the needs of young people argues James Forth.

One of the most dispiriting aspects of teaching is the realisation that you cannot learn your own lessons. While I may stand in front of Higher students ardent for the desperate glory of words, the truth is that I mix metaphors and add pleonasms almost as much as they do. So please forgive the mixed metaphor necessary to convey this article’s central concern.

Children and young people are being used as political footballs by a nation of Gradgrinds wed to a factory model of education. In their Dickensian mindset, education is a means to socially condition young people towards completing pointless tasks when someone tells you to because someone tells you to. This mindset believes that the primary role of education is to ‘prepare young people for work’ or to sublimate the better parts of their nature to fit the needs of the capitalist system – whichever phrase you prefer.

Much as I dislike the phrase ‘political football’, it does provide an apt description of the role of children and young people in this debate. They are kicked far more often than they speak. They are a means of achieving someone else’s goal: column inches, prominence or just a good old-fashioned Scottish protestant belief that one can only find meaning through unpleasant and unending work.

I really do wonder which, if any, young people Lindsay Paterson and the Commission on School Reform consulted when they suggested that the school day should be extended by eight hours. While, hypothetically, I accept that there could a few pupils in favour, I am going to guess that the answer is precisely none. Scottish school inspections assess whether each school involves pupils in decision-making. Even Scotland’s most authoritarian teachers are compelled to spend more of their time listening to pupil views than the Commission on School Reform.

Don’t be fooled by the officious nature of that title: the Commission is a persona of the right-wing organisation, Reform Scotland. Reform Scotland can generally be relied upon to clutter the pages of Scotland’s broadsheets with their haverings, but their proposal to extend the school day is likely to entice parents reaching breaking point after weeks of lockdown.

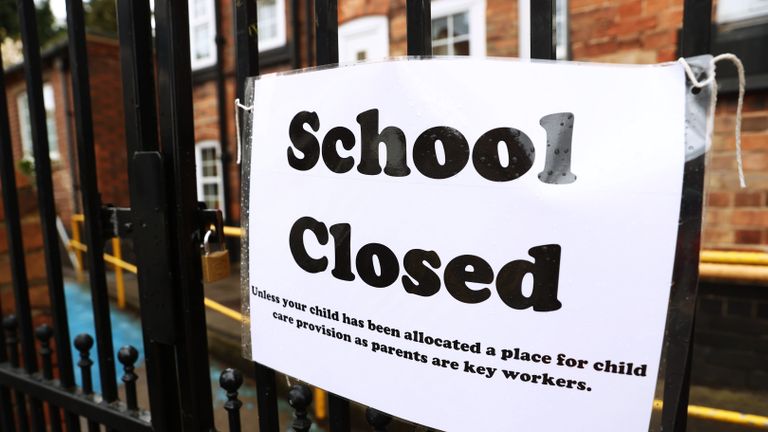

The proposal operates on a flawed assumption. It holds that if children are in school then they are learning while, if they are not in school they are not learning. Yet there are bullied children for whom this lockdown has been a blessing. In fact, for many young people, especially neuro atypical young people, lockdown served to highlight just how dehumanising cramming 30 children in front of one adult, in one room, learning the one thing at the one time is. As Jonna Schroeder put in the New York Times, what if some kids are just better off at home? I would add, what if others are better off on a flexible timetable? Why does everyone have to be in at the same time? Why are teachers allowed to work at a time and place of their own choosing and not students?

Lockdown should have inspired a wave of collective contemplation. With the ease that many predicted the end of commuting, we should have been prepared to ask whether a mode of education that spends more time teaching young people to conform than to think is necessary.

The response to the centre-right has been a familiar one. After the 2008 financial crash, they doubled down on the same neo-liberal economics that created the mess. Today, their response to the mental health crisis among school pupils is to recommend even more of the same discredited to nonsense: high-stakes testing, long hours in school and an authoritarian approach to behaviour.

Thankfully, the approaches above are mostly discredited among education experts. If you want to learn more, the likes of Barry Black, Mark Priestly and James McEnaney are far more eloquent than I am. However, the media that parents might read is dominated by a ‘catching-up’ narrative. The problem with this story is that it places an emphasis on academic learning. Microsoft Teams and Glow can make some attempt to simulate that.

Yet they cannot simulate social and emotional learning. What is the use of quadratic equations if you have not learned how to manage your feelings? What is the point of long division, if you don’t know how to show empathy to other people? A meaningful approach to educational recovery will have to place social development, and mental well-being, at its heart.

To achieve that we should not use young people for our goals, but to listen to them. Their suggestions will be as numerous as they are – recovery should look different in every school. However, I sincerely doubt that, from all those suggestions, there will be one for eight hours a week of additional, mandatory schooling.

The additional neo-liberal benefit of course is that if kids are in schools 8 hours longer, then parents can be in work 8 hours longer. And nurseries can maybe break even by charging for another 8 hours a week daycare for their younger siblings. Win-win for the suicidal death cult we call neo-liberal capitalism.

When are we going to make neo-liberalism a capital crime?

Besides, if we just rewrote the cirriculum so that kids are actually taught useful stuff, like how to make tools by hand, how to grow things without fossil fuels, how to heal people with nature, how to interact with other people, how to think for themselves, and the history of nature-destroying colonial extractivism, then they could probably be in school 8 hours less a week, not 8 hours more.

“Win-win for the suicidal death cult we call neo-liberal capitalism.” Exactly. And even better, lets hand our children over to the mega tech corps like Microsoft and Google to speed up the catch up process. Then they will learn what is acceptable thought and opinion and be profiled and surveilled before they can become a nuisance… and help increase corporate monopoly over our society and add to the top line profits – win, win, win, win. What is not to like!

The research I have seen suggests that the required school leaning can be done in about 2hr per weekday if you take away time wasted on crowed control and other nonsense distractions from the school room. School is a highly inefficient way to learn.

Learning is a 24-hour-a-day, seven-days-a-week, life-long process.

You comment is of course an over simplification of what we are talking about here. For example, most people benefit from a structured, focused and supported (mentored/taught) environment to learn to, say, read, or train as a medical professional/plumber/or how to write and essay etc etc.

But you are the ultimate wisdom on all topics in this comments sections so I will defer.

Yes, a structured, focused, and supported environment (discipline) is central to the factory model of education, which I thought we were talking about here, and in accordance with which children are equipped with socially useful skills.

The question I raise (and you can engage with or disregard it as you wish) is: What do schools-as-factories have to do with learning as personal development?

Your usual gaslighting Foghorn. I have rarely encountered someone who can sound so intelligent and yet convey such little meaning.

So… What do schools-as-factories have to do with learning as personal development?

If you actually read my comments and rather than reactivity respond to them, actually take the time to contemplate on them, you will find that your responses are redundant. Your gaslighting is trying to suggest that I’m in favor of the school system as it is (born out if the imperatives of the industrial revolution) – I’m not. Or that I think you can only “learn” within the confines of a class room – I don’t.

I have argued my whole life for flexible, mixed age, academic and vocational networks of community learning centers. As someone who had an usual educational upbringing (less than 1% of the population) this has been something that has been an open question in my life since I was a young child.

The problem with your addled and reactive way of engaging with people is that you don’t bother to take the time to actually understand (or check out) what the other person is saying.

Yes, I know. I agreed with you: ‘Learning is a 24-hour-a-day, seven-days-a-week, life-long process.’ But then you called this an ‘oversimplification’ and insisted that ‘most people benefit from a structured, focused and supported (mentored/taught) environment’ – that is, a factory eduction. I was just teasing out this contradiction to see where it would take you. Educationally, this is called the socratic method.

Again you willful misinterprete and reframe what I have said to fit with your meaningless interjections.

As a last attempt… are you saying that pre-industrial, pre-factory apprenticeships were somehow a misguided product of the factory system?

In the past I have found it to be pointless engaging with you as you are not interested in what someone has to say, only your interpretation of what they say. You pathologically gaslight. So I will not engage with you again.

No, I’m saying what I said; that ‘Learning is a 24-hour-a-day, seven-days-a-week, life-long process.’

Your proposal to rewrite the curriculum is informed by just what James complains of: the factory model of education; schooling as is a means of achieving someone else’s goal, some end other than the child itself.

The utopian goal to which you would have the child shaped might be laudable, but the child itself is no less instrumental to that goal than it would be in relation to the utopian goals of neoliberalism, say.

Education should be child-centred rather than a process of social engineering.

Or hear hear even!

Here here!

First of all, thank you for pleonastically introducing me to a word which was unfamiliar to me: pleonasm!

Joking aside, I liked this article as a riposte to the proposal of Professor Lindsay Paterson and others and the attraction of the particular paradigm of education and schooling which he, the media and many others are presenting as an unchallengeable norm. I liked, too, your acknowledgement that those who teach (and I was a teacher myself) must also put ourselves in the position of being learners, too: in fact, I would assert that teaching and learning are parts of the same process and each is dependent on the other. When we are teaching, we are learning and when we are learning we are teaching. Unfortunately, many are unaware of this symbiosis and perceive themselves as one or the other.

During the period of school and nursery closures, many young people have had the benefit of having both parents at home, as well as, in some cases, grandparents or other supportive adults. I have been heartened by the sight of so many fathers enjoying the company of their children. Despite the increasing and welcome shift over the past three or four decades of fathers becoming much more active in child rearing, economic pressures still push the majority of child care on to mothers. So, I think that a clear gain from the lockdown has been this increased father/child relationship.

School is important for young people in a range of ways and not just for the curriculum/assessment purpose. Schools are social places. Most parents when asked what they want for their children from school say, first, that they ‘want them to be happy ‘. They want them to make friends and learn how to engage socially. Most children, when asked who are good teachers, say that it is the teachers who care, whom they feel value them as people in their own right, who are the ‘best teachers’. This often includes ones who are seen to be ‘strict’. As one five year old said to Professor Brian Boyd, that ‘they are strict FOR you’. The children were aware from the range of actions by the teacher that when he/she was being strict, it was in a context of care and respect for the children.

It is my view that, on the whole, schools in Scotland, nowadays are happier places than they were when I first went to school (and I mostly enjoyed it and did well by the academic and sporting measures) and when I entered teaching at the start of the 1970s. There is no corporal punishment, any more! Comprehensive education has opened the full range of the curriculum to all young people. The ‘guidance’ and support system, on the whole has tilted schools to being more child centred. Much health provision has been deliver through schools. ‘Extra’ curricular activities have benefitted millions – which begs the question, ‘why are they ‘extra curricular’?

Now, as someone who has two university degrees, I value academic education, because it has, over the centuries, enabled us to live more enjoyable lives. So, I think that schools need to continue to offer rigorous academic experiences. It is the skewed assessment/testing/compliance/evaluation regime that has grown up that has distorted the school experience. Assessment and evaluation are essential components of teaching/learning and, necessarily have to continue. However, these, with things like school uniforms, have become instruments of control, which stifle the creativity of students and teachers and bring unhappiness to aspects of school life. They also influence some parents’ perceptions and expectations of school ( fortunately, more are aware of the control aspect and are more ready to challenge such things in the conduct of some teachers and school authorities.

In the early part of my career, mine and Professor Paterson’s paths crossed a few times and I was impressed by his insights, which I felt were based in a ‘liberal’ mindset. Some of the things he and colleagues were putting forward had the potential to be transformative. However, like many younger ‘radicals’, he has migrated across the political spectrum. He has not become some ‘right wing extremist’, but, he has become much more conservative and resistant to change, partly because he has become part of ‘the establishment’ (a fuzzy concept, but a useful shorthand.)

Like many of the ‘liberal’/newLabour group, Professor Paterson embraces the ‘meritocratic’ illusion, despite almost certainly being aware that, when Michael young coined the term, he was doing so satirically to highlight the vacuousness of it. Unfortunately, much of what Mr Young lampooned has become hegemonic, and not least in his unpleasant son, Toby.

I agree wholeheartedly with this, Alasdair. As the sainted Paul Feyerabend said: the end of education should be to make people smile.

‘Comprehensive education has opened the whole range of the curriculum to all young people’.

Even if that were correct, and I have reason to doubt it, the bar would be set low. Most parents, particularly from the middle class, view secondary school as a stepping stone towards tertiary education and a successful career. In this respect, some comprehensives are vastly more successful than others. Parents are willing to pay a huge premium – in housing coasts – to allow their children to attend a ‘successful’ secondary.

Our First Minister, briefly, made closing the attainment gap her first priority. Her actions suggested that she had little idea how to achieve this. (In fairness, I think it will be monumentally difficult.)

I doubt that Lindsay Paterson’s suggestion will be implemented though it is worth noting that he wants to increase the school week by 8 hours – not the school day as it says in the piece above.

It’s true insofar as those children who weren’t selected to attend senior secondary school were subsequently restricted to the much narrower curriculum offered in junior secondary school. The introduction of the comprehensive system in the 1960s put an end to that injustice.

Alasdair, thank you for taking the time to leave such a thoughtful comment. I would like to thank everyone who has commented, but I was especially pleased by this comment.

Very good article! Common sense well put.

However in balance it should be remembered that school is for some pupils a respite from less pleasant home situations.

Also, there are many caring teachers who, whether in person or remotely, do their best to give necessary individual attention.

My wife is a teacher.

As someone who used to dog school and go to the Mitchell Library instead, I applaud this article.

Good on you, Xeno! That’s the spirit! Take control of your own learning; self-direct it. Schools are just one resource; they don’t work for some kids, they do for others. Society needs to provide a broader, more comprehensive learning environment that caters for everyone, from cradle to grave. Schools without walls, as it were, where no-one is left behind.

The first question any learning facilitator (‘teacher’) should ask every morning is ‘What do you want to learn today?’