Interviewing Samar Ziadat about the Dardishi Festival

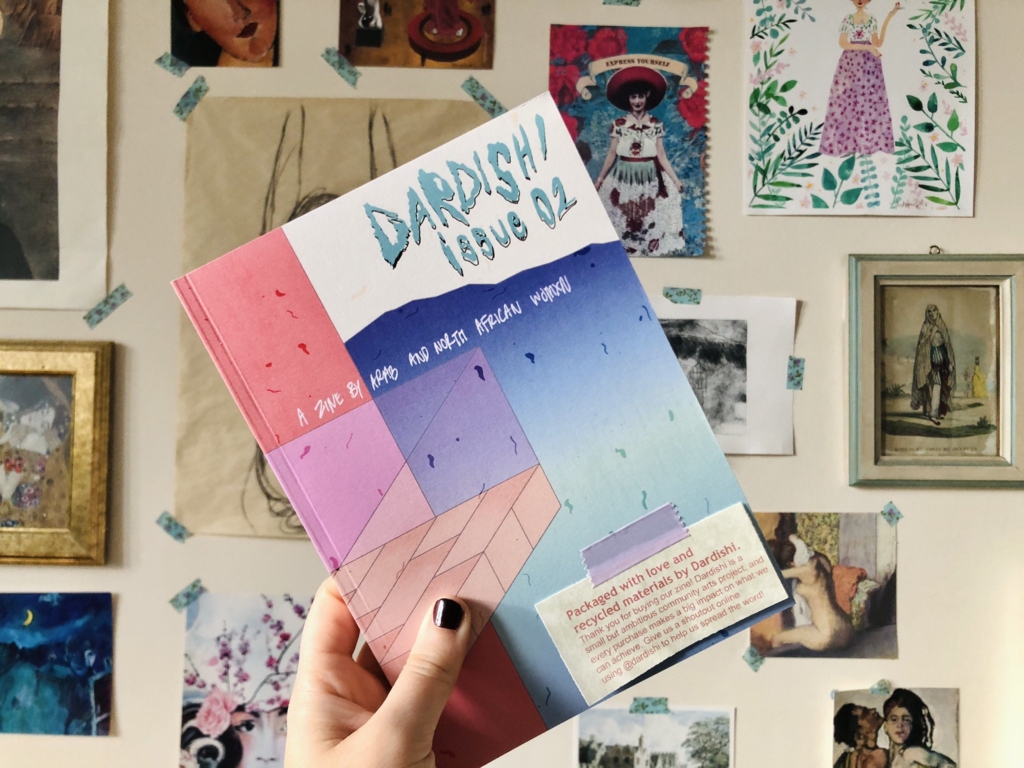

Over the past two years, the last few weeks of winter would have seen flurries of preparation ahead of Dardishi Festival, a Glasgow-based arts and culture festival dedicated to work by and for Arab and North African women. Starting out as a small community zine created by arts programmer and then-student Samar Ziadat and her sister in 2016, Dardishi has snowballed in scope and popularity over the past five years, now comprising a three-day festival, an annual zine showcasing Arab and North African women’s (inclusive of intersex and trans women) and non-binary people’s writing, and a year-round programme of events.

“We thought that the representation of Arab and North African women’s views and opinions and thoughts that were in the media at the time were either not representative of us and our friends and the conversations that we had, or that our opinions were being mediated through men or white people, or they just weren’t there at all,” Ziadat explains. “I felt very lonely, I felt isolated, I felt like I didn’t have comrades who really understood me and stood by me and who I could do the same for.”

It is perhaps fitting that, in the face of this cultural isolation, Dardishi’s output would focus so heavily on the communal and the accessible. “I thought this was the perfect political way to disseminate information in a democratic way online,” Ziadat explains of the initially digital, DIY format. “And it was also a freely accessible platform to use a website. Producing zines costs money, even if it’s not much. And then selling them takes time and we really wanted to provide that for free internationally. That was pretty important.”

This emphasis carries over into the yearly festival usually held in Glasgow’s Centre for Contemporary Arts, a festival that notably eschews the institutionalised colonialism and self-proclaimed authority that can be associated with arts programming in Britain for a celebration of creativity that is open, collaborative, and created by and for those normally excluded from the arts. “I initially thought I would be working in museum and collections-based work,” Ziadat explains. “A big turning point for me was working at CCA, because they don’t have a collection – they have an archive and an accessible library, both within the office and spotted around the venue, but they don’t collect.”

“I, at this point, don’t feel like it’s possible to decolonize a collection,” she continues, “because the collecting, categorizing, display of, and ordering of objects is to me heavily colonial in the first place, very white, very much rooted in European history. And […] that process of curating is very much done to the state’s people as well. That is very literal, […] if you look at the way that Black people were treated as objects in museums and put in displays. I just felt like there’s no way that we can step into these colonial buildings filled with colonial items and […] go in and re-scramble and jig about and fill in the gaps of this historical record that’s been ordained by white people. Why would I want to step into a space, take white man’s history, and try and shove myself into it? Honestly, maybe it’s a bit extreme, but I’m just like, set that on fire. […] I knew that when I started this festival that I wanted it to be nothing to do with that.”

Instead, Dardishi turns away from heavy reliance on curation and collections towards a more creatively symbiotic festival of workshops, community film screenings, and collaborations with other non-profit groups. “[It] feels really good not working with a collection but working with actual human beings who are doing work that is revitalizing, that speaks to us, that pushes people to think in new ways, or even makes learning as a concept accessible to people. Our school system is so at fault, and our universities are also tied to this colonial understanding of history and our understanding of the order of this nation and how we fit into it. I wanted something that creates an alternative space for self-directed learning, and that is engaging and accessible and exciting, and that encourages more Arab and North African women to create things.”

For Ziadat, the work that Dardishi does is inextricable from its broader context as a Scottish-based organisation. “I feel like there’s quite a bit of erasure in contemporary Scottish culture of colonialism. There is a decided separation from English or British history, which in many ways I understand why – and fuck the Tories – but also Scotland has been part of British colonial and imperial conquests throughout history, and to this very day the taxes that I pay in Scotland go towards bombing my people in Palestine. So there is no way that we can really separate that. [E]very political party in Scotland is an imperial one.”

And none of this is new information, Ziadat stresses. “Black women in Scotland have been talking about this since the beginning of time,” she continues. “I’m really inspired by artists like Alberta Whittle and Mele Broomes, and grassroots projects like Yon Afro, [who do] really exciting decolonial [and] anti-imperial work of Glasgow and Scotland more widely, and who talk about this very openly. I pay tribute to them in terms of where my learning comes from and my understanding of this place, which isn’t as safe as it felt like when I first arrived, for sure”.

As for the future of Dardishi, Ziadat is full of excitement. This year’s festival has been moved to June, and will be taking place online, which Ziadat hopes will diversify its pool of participants – both facilitators and audience members – even further. “There is no thought, voice or opinion that epitomizes or encapsulates the plurality of all of our experiences,” Ziadat explains. “[The more] people who are connecting, there’s a diversity of these thoughts and views and that’s so exciting. And I’m learning so much. I don’t proclaim to understand every facet of what it means to be Arab or North African or a woman or queer or disabled or any of these things. I can only represent what it means to me to exist in the world with these identities. And it has been such a joy to learn from everyone.”