Green Lairds and the Just Transition: Can rewilding save us from climate change?

Across vast swathes of rural Scotland, conservationists look at an empty and ecologically degraded landscape and see a source of hope. In the fight against climate change the land itself can be put to work. Meet the rewilders.

One fifth of the Scottish landmass is peat. 4% is native woodland. These are natural carbon sinks, with peatlands alone holding the equivalent of 140 years of our emissions.

The rewilding movement seeks to use nature itself to combat both the climate and biodiversity crises. Its advocates argue that large parts of rural Scotland have been turned into unproductive monocultures at the detriment of wildlife diversity. If returned to its natural ‘wild’ state through natural reforesting and the reintroduction of native species, the argument goes, the land would return to a healthier state and capture carbon.

But the future of land use is not merely a technical ecological debate. This is a fiercely contested question – and it is an issue that is coming into sharp focus as a new generation of investors seek to turn the dreams of rewilders into reality.

Most prominent is Anders Povlsen, the Danish fast fashion billionaire who is the UK’s largest private landowner. Povlsen’s Wildland Ltd has a “200 year vision” to “let nature heal, grow and thrive” across its large estates.

Such private, large-scale conservation attempts are not without their critics. Community Land Scotland, an umbrella group of community landowners, warn of an influx of “corporations, private individuals and institutional and absentee investors” seeking to buy large estates to take advantage of subsidies and the market in carbon credits. These new “Green Lairds”, CLS argue, are exacerbating an overheated land market to the detriment of local communities.

The description of these wealthy rewilders as ‘Lairds’ alludes, quite deliberately, to a powerful folk memory: of an earlier generation of landowners who emptied the Highlands of people in the name of progress.

*

Few periods in Scottish history have as deep and ongoing a resonance as the Highland clearances.

The period – in which powerful landowners forcibly removed people from their homes in order to raise sheep, and later deer – had a profound cultural impact. And those changes were driven by the industrialisation that launched the carbon age.

In the mid-eighteenth century around half the population lived north of the Tay. This proportion fell rapidly as the central belt saw a rapid urban expansion, driven partially by Highlanders moving south from agrarian to industrial work.

That central belt expansion was coal-fired. Coal was an essential ingredient in the creation of iron, which allowed the construction of bridges, railways, factory machinery and steamships. Glasgow, on the doorstep of the coalfield running across central Scotland, became an industrial powerhouse. From 1750 onwards, cities closest to coalfields grew substantially faster than those without such proximity.

This revolution in turn changed rural Scotland. The Highlands were well placed to meet the growing demands for goods such as wool and kelp, key supplies for the emerging textiles and chemical industries. But meeting this demand required a radical reorganisation of society. Traditional small farmers were pushed out to the coasts or beyond and their lands turned over to sheep.

At the same time landownership itself was changing dramatically. Industrialisation had left the Highlands a poor satellite to the wealthy Lowland economy. As hereditary landowners were increasingly forced to sell their estates under the threat of bankruptcy, there was no shortage of buyers – almost all from the Lowlands or England.

In some cases these new lairds were motivated by ideas of modernising and improving these estates. But often it was the ‘wildness’ of the land itself that was attractive. With the land emptied of people, affluent Victorians flocked to the region to enjoy tourism and bloodsports. The wealthiest amongst them sought an estate of their own – most famously Queen Victoria and Prince Albert themselves, who purchased Balmoral.

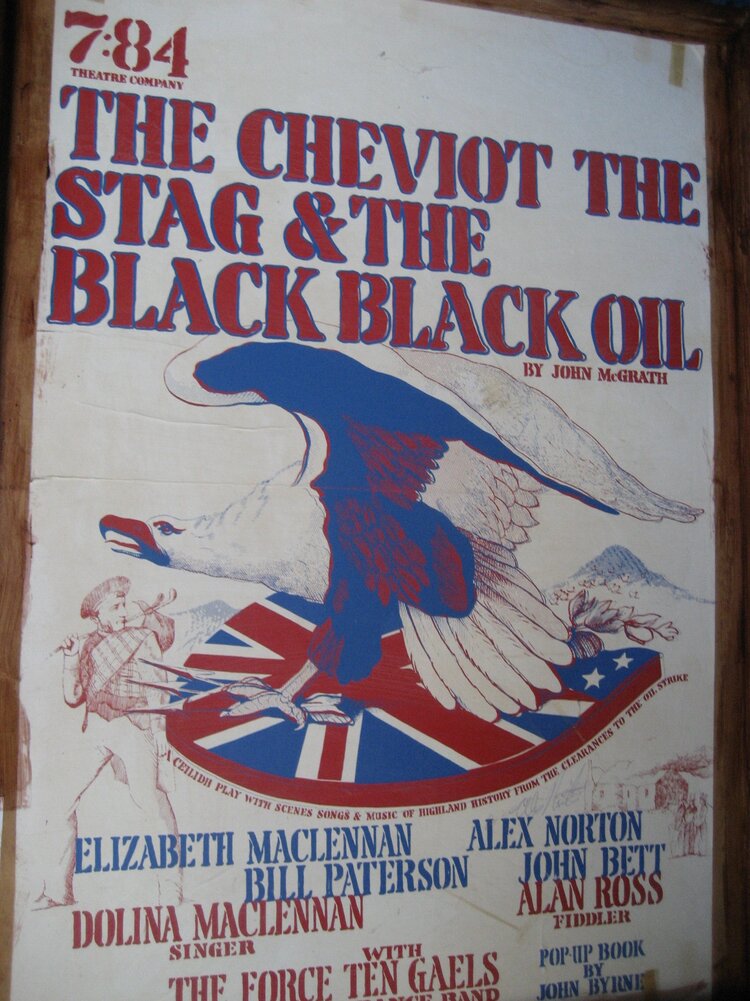

Images: Top, The Monarch of the Glen, Scottish National Gallery. Photo by Paul Hudson, published under Creative Commons. Above, poster for The Cheviot, the Stag, and the Black Black Oil. Photo by desomurchu archive gallery, published under Creative Commons.

This summer a group of prominent rewilders circulated an open letter calling for the Royal Family to rewild their lands, describing it as “a unique and historic opportunity to radically address the degraded state of nature on these islands”. Balmoral, they argued, could become a temperate rainforest.

The call was criticised by Magnus Davidson, an environmental and social researcher at the University of Highlands and Islands. Davidson said that the call to rewild Balmoral “perpetuates the myth of the Highlands as this wild landscape where you can introduce landscape-scale changes… which is problematic when you consider the social history.”

The social history cited by Davidson is that of a land that is not empty but emptied – it is not wild, but cleared. With many communities again facing the challenge of depopulation, this is more than an historic grievance.

The risk highlighted by Community Land Scotland is that a new generation of ‘improvements’ driven by external forces seeks to undo the ecological damage of the clearances without answering the social questions.

Community Land Scotland contrasts the Green Lairds with the projects undertaken by community landowners with tangible social benefits such as generating renewable energy, promoting active travel and improving energy efficiency, as well as managing woodlands and peatlands as carbon sinks. When empowered to do so communities can take effective climate action – which might even look like rewilding.

This is a lesson with a wider resonance. In an analysis of the distribution of low-carbon energy, the Strathclyde academic Fraser Stewart found that, while household-level wind and solar technology was most likely to be adopted by the affluent, community energy projects were more likely to deliver benefits to low-income communities.

*

In the mid-1960s the UK Government was grappling with a familiar problem: how to bring prosperity to the Highlands. In establishing the Highlands and Islands Development Board, the Scottish Secretary Willie Ross famously spoke of a collective guilt over the region’s history, saying that “for two hundred years the Highlander has been the man on Scotland’s conscience”.

The establishment of the HIDB was a rejection of the idea that the region should be insulated from the modern economy. The Scottish Office described the view that industry would “spoil” the Highlands as “part of the romantic double-think that would enjoy the Highlands, but deny them the means of life”.

While attempts to bring industry to the Highlands have met with mixed success, green energy could change that: the Cromarty Firth has been identified as having the potential to lead an industrial expansion in the next generation of offshore wind.

The ecological restoration of rural Scotland can play a key role in the transition from carbon. But for that transition to be just, it must be built on green jobs and shaped by communities themselves – to be repeopled, as well as rewilded.

This article was first published at Scotland and Carbon – which states: “Scotland & Carbon exists to examine the ways in which our economy and our society have been shaped by carbon – and how that historic legacy is shaping our transition to a post-carbon world.

The point is not to wring our hands about an inherited ancestral guilt – or, as Christopher Silver describes it, to pay penance for “some kind of carbon original sin”. We should be much more hopeful than that. By understanding the forces that have shaped our modern reliance on carbon we can better understand how to escape it.

Imagining a world without fossil fuels is difficult. A sense of historical perspective can help us do so.”

Sources:

Community Land Scotland, Act on land to counter twin threats to Scotland, August 2021

T. M. Devine, ‘Highland Migration to Lowland Scotland, 1760-1860’, The Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 62, No. 174, Part 2 (Oct., 1983), pp. 137-149

John Turner, What can we learn from the role of coal in the Industrial Revolution?, Economics Observatory

Alan Fernihough, Kevin Hjortshøj O’Rourke, ‘Coal and the European Industrial Revolution’, The Economic Journal, Volume 131, Issue 635, April 2021

Eric Richards, ‘Structural Change in a Regional Economy: Sutherland and the Industrial Revolution, 1780-1830’, The Economic History Review Vol. 26, No. 1 (1973)

T. M. Devine, Clanship to Crofters’ War: The social transformation of the Scottish Highlands (Manchester University Press, 1994), pp.63-83

Kirsteen Paterson, Campaign to rewild Balmoral criticised by leading land reform expert, The National (13/06/21)

Fraser Stewart, ‘All for sun, sun for all: Can community energy help to overcome socioeconomic inequalities in low-carbon technology subsidies?’, Energy Policy, Volume 157, October 2021

Andrew Perchard and Niall Mackenzie, ‘‘Too much on the Highlands?’ Recasting the Economic History of the Highlands and Islands’, Northern Scotland, Vol 4(1) (2013), p.12

The National Archives Website: Discovery: The Scottish Economy 1965-70: Draft White Paper, p.56-8. Available from https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D7660228

Experts focus on Cromarty Firth for offshore wind, BBC News, (20/8/21)

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

Lairds have already been massively enriched at the expense of tenants since the single farm payment was scrapped in2014

Tenants owned the sfp entitlement and had to be left in situ paying rent

Scotgov were lobbied for 10 yrs to change that by SLE and it worked.

Tenants now get the heave ho and the landlord gets the money

Is that social justice ?

How to bring prosperity to the Highlands.? I know! Sell it off to FOREIGNERS who will look after it for us. ( cos we’re too wee, too stupid, too poor etc)….I include that wee fat German wumman up at the palace…and the English government who dump nuclear weapons on OUR land.

Know of any other country that allows FOREIGNERS to own large swathes of their land? Try it and see what happens.

Scotland will be in the hands of the Scots. ..so Mr Povlsen,Arabs,Belgians, English and other FOREIGNERS like you..go and buy in your own country and stop treating OUR land like an investment. Independence is looming…..an’ oh whit a panic should be in yer breastie…

I’ll think you’ll find that most of central London/Paris/Barcelona/New York/LA ad infinitum is owned by FOREIGNERS.

Nothing like a good old rascist rant……

We should all just stay within 2 miles of where we were born and keep those bloody FOREIGNERS OUT.

Yes, we really do need significant land reform and wider community ownership. Land and wealth taxation has to be brought in.

The iniquitous increase in National Insurance along with rebranding to give a more ‘marketable’ name is yet another transfer of wealth from the majority of us to the people who run the Westminster Government.

TM Devine also wrote The Scottish Clearances.

Fascinating piece – thanks for bringing some of the complexities forward with both clarity and grace. I haven’t come to any definite position on this but this excerpt seems to reflect in some ways the conversations in Canada around reconciliation and the need to find a new way forward with indigenous collectives here on Turtle Island.

I still don’t think justice would be served by the further privatisation of the land to community ownership. It would be best served by nationalisation, the charging of rent for all and any private use, and the equal distribution across society of the revenue raised.

Hmmm… Industry could go underground thus preserving the landscape. There is a mountain with a power station inside it on Mull. Wind turbines could be designed to blend in more with the landscape (green paint?), as could solar panels. With a little bit if creativity we could have a clean industry as well as the landscape.

I read that historically forests were always well populated in the middle ages with charcoal burners and others. We could revert to this.

Wouldn’t charcoal burning be outlawed in a green dictatorship? I thought the idea was to keep all that carbon locked up.

Burning wood is carbon neutral.

Where is the “Green Dictatorship”? Is it only in your head (or facebook feed) ?

You do know what a dictatorship is don’t you?

Yes, dictatorship is the state of public affairs in which ‘power’ (decision-making) is concentrated in the hands of a single ‘speaker’ (‘dictator’), which speaks with universality and authority and seeks by coercion and/or exclusion to abolish political pluralism and the mobilisation of the general or collective will that such pluralism generates.

The dictator can be an individual, a party, or a community of interest or ‘class’. It can be elected or non-elected.

A green dictatorship would be a state of public affairs in which decision-making was concentrated in the hands of the environmentalist movement and its supporters. It is currently, of course, only aspirational.

Actually, you could bury the charcoal in the soil. In the Amazon such soils are called Terra Preta. The process we use is called pyrolysis, and produces a product called biochar. The carbon remains locked in the soil for centuries – it is massively useful in improving soils – with water and mineral and nutriment retention. It could be by far the most effective and cheapest de-carbonisation of our atmosphere if conducted at scale. I live in NZ and near here a local operation does this on a small scale, selling the biochar to orchardist and growers in the area. You can use any sort of organic waste to do this, or you could grow coppice of all sort of plants and trees to achieve this on a large scale. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/sep/30/biochar-production-climate-change

Aye, I remember reading something about that a couple of years ago. I presume that you don’t subscribe to the view that charcoal production, even at a sub-industrial level, is one of the causes of deforestation and that this is why it’s now (usually) illegal in South America and Africa and (nearly always) unregulated.

Biochar is currently being touted as a means of carbon sequestration and mitigating climate change. However, charcoal burners (with whom you’re proposing to somehow repopulate our woodlands) don’t produce biochar.

But it wouldn’t do any harm for us to process more of our organic waste in this way. Unlike charcoal burning, it’s non-extractive and releases far fewer emissions than composting.

(BTW from where are you going to conscript all these woodland charcoal burners you’re proposing to repopulate the forests with?)

Thank you, Dan. The idea of re-wilding in the context of the near desertification of so much of the Scottish Highlands is non-arguable to anyone with any appreciation at all as to just how transformative this would be – in beauty and in value, both moral and financial. And any claim that such is inimical to repopulating or regenerating social activity in the Highlands is an obvious false dichotomy, indeed the opposite almost certainly applies.

You allude to the problems of private gain from the public purse, in regard to tax breaks, subsidies and the ETS (this latter is a con, of no provable environmental benefit, almost certainly deliberately designed for manipulation and profiteering, and should be abandoned forthwith.) The basic, fundamental and unavoidable problem is the private ownership of land, everywhere. Whether its farm land, development land, land traded for speculation or sporting estates, whatever. Land ownership brings almost total power on how the land will be used. Land, from the Australian stations the size of countries, to the back garden of your terrace house, is someone’s personal fiefdom. Every landowner is a Laird. Obscene amounts of money are made by those speculating in land, developing land in inappropriate or destructive ways, using land to hide wealth from the authorities or manipulating treasuries in their taxes or subsidies. Unsustainable land use, top soil degradation, waterway pollution, dead sea zones, land erosion, flooding, pollution, ecological collapse and insect and species loss are almost the norm now in all countries and societies as the maximising of profit from this autocratic relationship with the land continues. The financialisation of land, a finite and non-expandable resource, has a parallel the speculative nature of another restricted resource, that’s Bitcoin.

I believe all land should be nationalised, be citizen owned land, . To allow though the wise use of this land, leases, of variable maturities, should be purchasable by those individuals or organisations that can demonstrate they are indeed capable of wise use of this land – and there’d need to be particularly strict criteria for anyone investing from outside the country.

Whether one would actually be able to achieve this, or whether some sort of half-way house of land control, rents, speculation tax, or land tax – the fact is that with soaring land prices, with its speculative tradeability, have become too high to allow the fair functioning of our democracy. Land ownership is one of the most obvious ways in which inequality is entrenched in any society, and is worsening. In that this effects one of the most obvious and vital human rights, the right to a decent, affordable home, whether bought or rented, that is robust and adequate enough for a happy and healthy life as an individual, a couple or a family, then society collectively has to tackle this very serious and growing problem.

https://landforthemany.uk/preface/ This proposal to the UK Labour party for policy discussion is introduced by George Monbiot. It is well worth reading and contains many principled proposals. They are only revolutionary in the sense that the French populace, in the face of implacable privilege, in demanding justice and fairness for themselves, were revolutionary. In any parallel universe with an ordered UK society such principles would likely be the norm.

The hyper-capitalist system we now live in is inimical to our very existence as a functioning and healthy society and you have to be at least 55 years old to remember and understand a time before this. The Belle Dame sans Merci of such capitalism, Margaret Thatcher, once infamously stated “There’s no such thing as society…” so it shouldn’t be a surprise that in the system she helped construct, society is now literally falling apart – how can one nurture a healthy society if one doesn’t even recognise its very existence? How can one nurture a healthy environment when that environment is treated as if it were some great capitalist self-repairing perpetual motion machine that fuelled by money today will somehow miraculously make even more money tomorrow and continue to do so for ever?

Thanks for your time. Scotland, put the whisky down, eat your porridge, and take some effective action in controlling your own affairs. I would suggest that a new department be set up in your independent nation, that’s a Department and Minister of Moral Philosophy, to provide guidance at a time of revolutionary change and existential crisis. In particular this department would promote and support a new Scottish Ecological Enlightenment. Scotland has a unparalleled history of providing some of the most important intellectual moral, political and economic guidance to the whole of Western society in the past 200 years, it’s now urgent that you renew this effort.

You get off to a great start here, John, with your call to nationalise all land. But then you spoil it by going on to suggest that it might then be reprivatised in favour of (‘sold to’) those who can demonstrate to some authority that they’ll use it ‘wisely’, according to the determination of that authority.

No, social and environmental justice would be best served by taking all land into inalienable public ownership. People might then rent land for private use (e.g. for residential, business, or leisure purposes) at a price commensurate with the full social and environmental cost of the use to which they put it.

In feudal times all land was owned by the king and the Aristocracy were granted the use of land for various reasons.

Are you now suggesting that we revert to this with the monarch replaced by some nebulous authority ( and authorities are prone to corruption) and that those householders who have paid off their mortgages have their property confiscated unless they start paying a rent determined by that same corruption prone and inevitably greedy authority?

This sounds pretty left wing fascist, if not totalitarian, to me. It also assumes far too much goodness in human nature. We have only to think how the idealism of various revolutions in the 20th century or earlier turned into oppression.

Indeed, I do present land communism as an alternative to the capitalist model of private ownership or disposal, whereby all land is owned by the state (held at the disposal of the commons) and fed out to private use in return for a fixed charge. Essentially, this is indeed the pre-capitalist feudal model, only with the land being held at the disposal of the commons rather than of the lords.

You really think this will work?

to me it sounds like a prelude to Stalin’s execution of the Kulaks (some who were not rich by any means – A house and a few goats) or Mao’s cultural revolution.

We have seen how this worked in Russia, China and Cambodia to name but three.

How will you prevent the commons being as oppressive as whatever they represent? Think of councils raising council tax each year so the leaders can have enormous salaries.

And why should people have to pay to live on land they own mortgage free? Amazonian Tribes, for example don’t.

What we have is not perfect. Human nature will ensure that what ever replaces it is at least as bad.

Unless we take steps to stop that happening, to prevent power crazy psychos dominating the new society as they did left and right wing fringe movements. Socialists like freedom no more than fascists.

This is the general problem of government: how do we ensure that its power cannot be used oppressively. The solution is to institute a set of democratic checks and balances that are sufficient to prevent tyranny and other sorts of power abuse of which you give examples; a democratic constitution, in other words.

But let’s keep a bit of perspective here. What I’m proposing is that, as a society, we nationalise the land and distribute the revenues raised on its private use in a way that would serve the common good rather than private profit. I’m not proposing that we should put private landowners up against a wall and shoot them.

NO.

What you are proposing is that someone who currently owns a small piece of land, outright, with a home on it, should now have to pay a rent determined by an inevitably greedy undefined authority without recourse to appeal, with no clear benefit to the owner and, in practice owners who cannot afford to pay the rent will be made homeless.

As you can tell I have little trust in human nature. We do not need just checks and balances, we need a culture that does not reward underhand practices whether in business, politics or governance.

Land value tax REPLACING council tax might work though but that is a different matter.

Well, nor quite. I’m proposing only that those who currently own land for their private use would have to rent it from the public instead, on a full cost recovery basis. I’m making no proposal at all as to how this rental arrangement would be organised and managed. You seem to be automatically assuming that it would be organised and managed badly. Why would that necessarily be the case?

“You seem to be automatically assuming that it would be organised and managed badly. Why would that necessarily be the case?”

I cannot think of an example of such a reform that was managed and organised well and not hijacked for the benefit of the rich and /or powerful.