Beyond Cambo

The news that the oil giant Shell has pulled out of the Cambo development is a huge blow to the project, though whether it is a terminal one remains to be seen. A statement from the company said: “After comprehensive screening of the proposed Cambo development, we have concluded the economic case for investment in this project is not strong enough at this time, as well as having the potential for delays.”

Tessa Khan, director of Uplift, which is coordinating the Stop Cambo campaign, said: “The widespread public and political pressure is what’s made Cambo untenable. There is now broad understanding that there can be no new oil and gas projects anywhere if we’re going to maintain a safe climate.”

Philip Evans, oil campaigner at Greenpeace UK, said: “This really should be the deathblow for Cambo. With yet another key player turning its back on the scheme the government is cutting an increasingly lonely figure with their continued support for the oil field.”

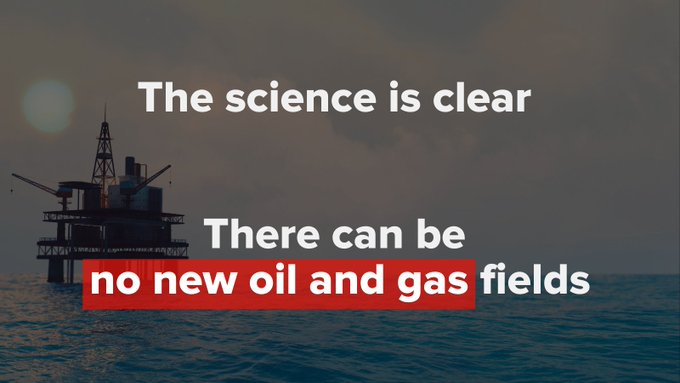

In dark times a victory like this needs to be celebrated and nurtured and used as a stepping-stone to more. For many young activists this could be the very first taste of victory, the idea that you actually can affect change. It also comes in the face of considerable obstacles. The mainstream media is tethered to a framing of the debate as about environment versus jobs and is seemingly unaware of the scientific reality we are living in. The International Energy Agency, the global energy watchdog, produced a report in May saying no new oil and gas exploration and development should be conducted after this year, if the world is to stay within 1.5C of global heating, the target the UK made the focus of the Cop26 summit.

Broadcast and print media regularly put out content that is little more than dystopian absurdism about how ‘new oil fields will fuel the just transition’ and words that just don’t have any logical sense. And there is the physical distance about oil fields. You can’t ‘get at them’ like you can with a pipeline or a road-building project.

The project may not be ‘stone dead’ yet but it is still wounded by this development, and you can watch the political fall-out as political parties shift.

Yes the First Minister was dragged from a position of climate-disastrous ‘neutrality’ to eventual opposition but she is also stymied by the fact that energy is a reserved matter. But her public opposition is significant and it does matter.

The Labour party, at a UK level anyway are also changing. Ed Miliband said: “This is a significant moment in the fight against the Cambo oil field. It makes no environmental sense and now Shell are accepting it doesn’t make economic sense. Ploughing on with business as usual on fossil fuels will kill off our chances of keeping 1.5 degrees alive. Cambo carries huge risks for investors as it is simply an unsustainable choice. Shell have woken up to the fact that Cambo is the wrong choice. It’s long past time for the government to do so.”

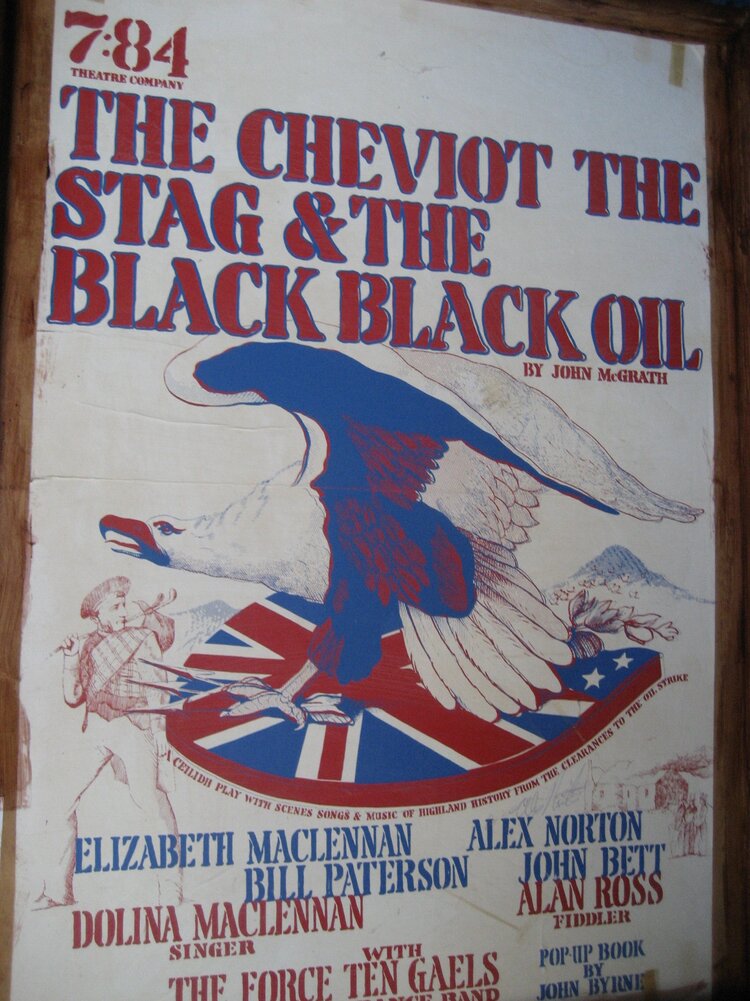

In terms of political movement we now have the strange phenomenon of the Tories and Alba now being the only political parties that support the development. Both are seeking a foothold from their supporters in the North-East, for a long time Alex Salmond’s fiefdom. Alba mould themselves as of the old-school left, drawing on the symbolism of Scotland as an industrial nation, a nation of inventors and workers. This is a rich vein of social memory but it doesn’t trump climate reality nor Salmond’s personal ratings.

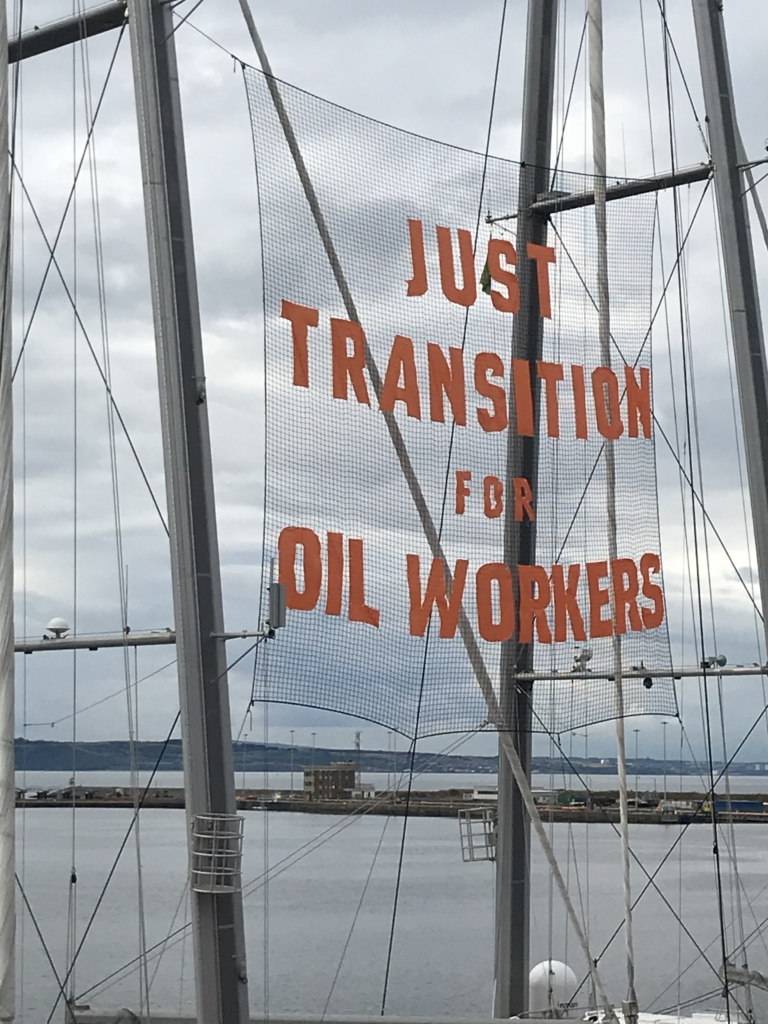

But the challenge of jobs in the oil and gas sector and how to transfer them is very real, and the mantra of ‘just transition’ has been largely pitiful. The languishing shipyard at Burntisland testimony to the Scottish Government’s impotence and failure in this regard. Sturgeon and her colleagues are making a calculated risk that they can make moves towards speeding up and intensifying the transition process, but they know and we know that they are not in control of the sector and its drivers. So we are in a conundrum that a pivotal part of the story about how Scotland gains independence and sees itself as a modern viable entity is not something that Scotland itself has control over.

This is one of the reasons to celebrate the new development at Nigg. Nigg Offshore Wind (Now) will be the UK’s largest offshore wind tower factory, opening in 2023, it will create more than 400 full time jobs. The site, north of Inverness will be 450 metres long and will cover an area of 38,000 square metres, “equivalent to more than five football pitches.”

It’s big.

The project is a consortium of corporate and government bodies. The £110 million project is a joint operation between Global Energy Group (GEG), which has its headquarters in Inverness, and Spanish offshore wind tower manufacturing specialist Haizea Wind Group.

A GEG spokesperson added that construction is expected to start in January next year, with site preparation and commissioning expected to take about 18 months. GEG added that staff historically employed in the oil and gas industry, will have the opportunity to be re-trained and up-skilled at the Nigg Skills Academy. The factory is expected to receive funding support from the Scottish Government via Highlands and Islands Enterprise.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said: “We need bold, collective action to tackle the global climate emergency, and the growth of our renewables sector over the next 10 years will be truly transformative, helping to deliver a just transition to net zero and a greener, fairer future for us all. We are delighted to financially support this cutting edge offshore wind towers facility, through Highlands & Islands Enterprise.”

This is a great development but there will need to be more.

Three other observations are worth making about the importance of the just transition’s role in the process of moving towards Scottish independence.

The first is that the expectation that all workers involved in oil and gas will be able to move seamlessly to high-skilled identical high-paid employment in the same location seems unlikely. Tens of thousands should be able to in transferable skills as the whole sector is dismantled and shut down and replaced by the likes of Nigg Offshore Wind. But not all will. Tempering expectation about what just transition is and isn’t is essential to its success.

Second we need a variety of scale of approaches and development. Projects in tidal, onshore wind, pump-storage and solar don’t all have to operate at the gigantic scale of the Nigg yard. In fact creating a landscape of smaller community-based renewables is much more likely to mean that the Scottish Government has control over their developments. Smaller-scale energy projects also tend to be ones that can be community-owned and can give long-term resilience to energy prices as well as contributing to the circular economy.

Finally much of the defensive narrative about why we need to keep Cambo has been centred around some key myths about fossil fuel imports and exports. But always absent from these debates is how we are making rapid and deep cuts in our own oil and gas use. How are we facilitating people to make that change? Where is the Energy Descent Plan for Scotland? The ‘just transition’ is not just from jobs in the oil and gas sectors it is from our own use of fossil fuels. Stopping Cambo is a huge victory but it is incomplete without this element of the movement. A vision of what are we for as well as what we are against is needed now.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

“In dark times a victory like this needs to be celebrated and nurtured…”

In these dark times which were brought about by a combination of factors. These include energy suppliers whose focus is on profit, not resilience. What the folk of the North East have experienced over the last week is a picture of the future where everyone is dependent on electricity. Electricity from unreliable – but green – sources, and from supplies from abroad including ever-reliable France. “Dark times” ahead indeed, with no heating and no lights.

If the past fortnight has not been a wake-up call for the abandonment of Net Zero etc then we are all surely doomed. We are sitting on reserves of coal, of oil, potential for hydro and nuclear power, yet we are chasing unicorns. We should be reminded of Ebenezer Balfour of Shaws, sitting in his cold house, subsisting on cold porridge, when there was a chest full of gold in the back room.

But the ‘dark days’ experienced by the people of rural Aberdeenshire were not due to the unreliability of the generative source of their electricity; they were due to the powerlines coming down. The matter of whether the electricity those powerlines carried was generated from coal, gas, nuclear, wind, or wave power is irrelevant.

And Ebenezer was infinitely wise: you can’t eat gold; the ‘gold’ of fossil fuels is toxic.

It sounds to me as if shell are saying they cannot make a profit unless the UK government subsidises us.

I read an article, a year or two back, suggested the carbon bubble and hence the oil Industry are about to collapse, the tipping point being where investors stops investing in oil.

Part of me wonders if WM manipulated this so they can claim the oil is running out. Another part says don’t be silly, they aren’t that clever or powerful. But it is worth keeping the possibility in mind

Shell is withdrawing because the economic case for investment in the Cambo project is not strong enough at this time. This might change (though I doubt it), in which case Shell would be back on board.

Horses.

If the government, any government, was wise, they would be commissioning a massive horse breeding program. Not show or race horses, but stout working horses to pull carts and canal boats and so on.

If a fossil fuel worker seeks transition, it would be to food growing, eco-systems planting or horse breeding. Anything else just speeds up the collapse.

Superb, needed, and now going out to as many as I can tag. Continue, Michael!

The Reid Foundation has just published a paper on Just Transition by Eurig Scandrett from Queen Margaret University. He notes that JT is one concept with many meanings among those referring to it. Some of these meanings are so weak as to exclude any mention of workers or unions (XR). Scandrett argues for workers, unions and environmentalists to adopt a ‘strong’ JT where “the collective action of workers through unions set the agenda and determine the parameters for the transition in deep dialogue with the environmental movement, whilst the state leads the transition plan on this basis.” The Just Transition Commission established by the Scottish Government following lobbying by the Just Transition Partnership (an alliance between STUC, unions and Friends of the Earth Scotland) seems to be a halfway house between the two and, although including unions and community voices, still allows business to set the agenda.

https://reidfoundation.scot/2021/12/beyond-just-transition-paper-now-available/

I think the conclusion that Eurig reaches in his paper even before ‘the collective action of workers through unions set[s] the agenda and determine[s] the parameters for the transition in deep dialogue with the environmental movement’ is spot on:

“Industrial strategy to stimulate jobs in the new economy is a necessary, but not sufficient criterion for just transition. What is also needed is separating income from wage labour in the first instance, and quality of life from consumption in the future.

‘As Carley and Spappens (1998) described it, social policy must aim, not just for efficiency, in the sense of producing goods and services with fewer resources, but also for sufficiency: generating a good quality of life with fewer goods and services. The union movement would add that such sufficiency must be equally distributed so that quality of life is universal, and not achieved for some at the expense of others. Quality of life will need to be based less on the purchasing power that drives high consumption, and more on good, accessible public services and more ‘life’ in the work-life balance. It will involve less dependence on employment and more emphasis on the quality of life of working people. The union movement needs to emphasise the necessity not just of more jobs, but of sufficient socially useful work distributed fairly and a good quality of life.”

Clearly, Eurig thinks that this is the conclusion those unionised workers ought to reach in their ‘deep dialogue’ with the environmental lobby.

But what if they don’t? What if they stubbornly insist on a good life based on being rewarded with ever-higher levels of disposable income and consumption rather than on an equal share of fewer goods and services? What if they don’t arrive at the ‘correct’ answer?

What if they had a choice between the two options, or even a third option, though I have no idea what that might be?

Suppose it could be decided on an individual basis that and they could swap from one to another? Perhaps the young would take the wage and consumption driven option and swap over as they got families or reached a mature age. Who knows.

There IS no correct answer, but our culture, which drives us to enter wage labour and often burn out is a problem not an answer.

I worked with Eurig many years ago on environmental justice campaigns.

But this is a problem and the stakes may be too high for enlightened workerism.

This is very much aligned with my goals and values: “social policy must aim, not just for efficiency, in the sense of producing goods and services with fewer resources, but also for sufficiency: generating a good quality of life with fewer goods and services. The union movement would add that such sufficiency must be equally distributed so that quality of life is universal, and not achieved for some at the expense of others. Quality of life will need to be based less on the purchasing power that drives high consumption, and more on good, accessible public services and more ‘life’ in the work-life balance.”

I think the debate about who is the agent and the object in ‘Just Transition’ is ongoing and indistinct, but I think the participants are wider than just the workers affected. By definition the climate reality means that the whole of society has stake.

I think Eurig’s report is strongly arguing that the workers whose livelihoods depend on the traditional energy sector shouldn’t be excluded from the decision-making that will define a just transition and not that they should have any privileged voice in that decision-making. I’m just not convinced that they would bring to the table what he reckons they would bring; namely, a commitment to the anti-growth agenda. I see no reason to suppose that they would readily swap the aspiration for ever-higher levels of disposable income and consumption for an equal share of fewer goods and services.

And is anyone ‘in control’ of the process by which we define a just transition? Surely, that process is one of political struggle between rival and, in some respects, competing interests, which is a process of which no one’s in control.

“I’m just not convinced that they would bring to the table what he reckons they would bring; namely, a commitment to the anti-growth agenda.”

Neither do I.

I am not sure what you mean by ‘enlightened workerism’. if it’s simply a naive belief that, faced with choices such as agreeing to make themselves redundant, or to accept poorer pay or conditions, workers will of course make the ‘right’ choice in the public good, then that’s clearly unreliable. But that’s not my interpretation of Scandrett’s argument. He gives some space to the example of workers manufacturing armaments at Lucas Aerospace in the 1970s. Faced with the company’s decision to close down their factories in response to market forces, the shop stewards organised an alternative plan to repurpose their skills towards socially useful products. The point here is that, faced with unavoidable change it was the workers who had the skills and motivation to find creative and socially responsible solutions.

And inevitable change is what we face now. The option to continue to work in unsustainable industries, or to choose higher wages and consumption rather than leisure time (or simply unemployment) is illusory. It’s simply a matter of when. There is an analogy used by the Transition Town movement about being on an aeroplane and discovering you don’t have enough fuel to reach an airport. You choice is stark: do you make a controlled descent and try and land as best you can, or do you just do nothing and plummet to the ground when the fuel runs out. Allowing the crew and passengers to decide doesn’t require us to believe that they will nobly go against their own interests for the common good.

At some point sooner or later it will become inescapable that fossil fuels can no longer be extracted and consumed (the sooner the better in terms of climate change). When that happens the assets of Shell, Exxon, BP etc become worthless. Those corporations effectively become insolvent and lose their wealth and power. For all those still employed by them, they are on the plane that plummets to the ground. You don’t need to be enlightened to want to avoid that, just awake.

‘When that happens the assets of Shell, Exxon, BP etc become worthless. Those corporations effectively become insolvent and lose their wealth and power. For all those still employed by them, they are on the plane that plummets to the ground.’

When that point is reached in the life of their business, won’t these companies rather just disinvest from those exhausted business areas and transition (transfer their assets) to some other still profitable line? I can’t see their planes plummeting to the ground.

Thanks Gordon, yeah that makes much more sense thank you

The value of fossil fuel corporations is derived from the expected return on their assets. It is fictitious (but real) capital. The assets in this case are the total oil, gas and coal reserves they have licence to extract (or are expected to get) in the context of developing technologies ability to do this profitably: the expected return on investment (this is different from the Energy Return on Investment which determines costs). If the reserves can no longer be exploited (or to the extent envisioned when investment was made for their development) they are devalued, creating a financial crisis for the asset holders. This is why oil companies are fighting tooth and nail to avoid real carbon zero measures. For them it is an existential battle for survival as profit making entities, and profit making is their reason for existence.

It is not dissimilar to the position of Big Finance in the crash of 2008. When the scale of bad debt was revealed, their assets (the expected return on debt issued – more fictitious capital) could no longer be valued. They were effectively insolvent. The only options for governments then became either 1. Let them go under and try and clean up the mess afterwards, 2. Nationalise the companies worst affected and absorb the bad debt, 3. Borrow or create money to pour in to the insolvent companies or buy up their bad debt.

If nothing is done about the fossil fuel industry until it hits the wall, the financial crisis that causes will go far wider than just the extracting companies (and will of course have criminally delayed the actions necessary to slow global heating).

‘If nothing is done about the fossil fuel industry until it hits the wall, the financial crisis that causes will go far wider than just the extracting companies…’

Precisely! As Lenin said: give capitalism enough rope and it will hang itself. Bring it on!

However: ‘The value of fossil fuel corporations is derived from the expected return on their assets. It is fictitious (but real) capital. The assets in this case are the total oil, gas and coal reserves they have licence to extract (or are expected to get) in the context of developing technologies ability to do this profitably…’

This is the case for the farming industry generally, of which fossil fuel extraction is an instance. Any farming business is only worth the cash value of its next harvest. Indeed, any business is only worth the exchange value of its liquidised assets. That’s why, in any sort of business, it’s unwise to put all your eggs in one basket. I’m confident that the assets of global corporations like Shell, Exxon, et al. are sufficiently diversified to ensure they will weather the transition from fossil fuels.

Also … ‘the collective action of workers through unions set[s] the agenda and determine[s] the parameters for the transition in deep dialogue with the environmental movement’ … in what sense is the ‘environmental movement’ in control of this process. It’s not.

Should any one movement/group/community be in charge of this?

No we should be in collective charge of it in a democratic society. Citizens Assemblies that are mandated could be part of that process.

So… who’s going to be in charge and control of assembling those assemblies? It’s a nice idea, but… how exactly?

This is already happening (here). The process of assembling people by lot goes back to Athenian democracy, its not difficult, see our coverage of Icelandic attempts at mass participation in creating a new constitution for example (hang on)

See here:

https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2014/07/25/crowdsourcing-the-constitution-lessons-from-iceland/

Yes, I know; I did a bit of work for the Pirate Parties International back then. And I’m a big fan of sortition. The original 2009 Icelandic National Assembly was organised by private individuals following the Pots and Pans Revolution that emerged from the financial crisis.

But the fact remains that, despite all the talk of citizens assemblies, no one’s managed or (I suspect) even tried to organise one in Scotland – or even in any part of Scotland with a population size comparable to that of Iceland. Why is that? What’s stopping us?

I mean: really, what’s stopping us? Why the reluctance on the part of ‘activists’ here to activate a citizens’ assembly?

See: https://www.citizensassembly.scot/

Thanks for this, Mike.

I note that the assembly wasn’t assembled randomly by sortition, but was recruited and selected according to criteria defined by a consultancy firm and by methods defined likewise by that firm. Why didn’t the organisers just randomly pick 125 jurors from the register of voters like the Icelandic activists did in assembling 1,200 of the 1,500 jurors for Iceland’s National Assembly in 2009 (the remaining 300 being allocated to repesentatives civic organisations like churches, trades unions, and chambers of commerce)? What was the reason for the Scottish jurors being screened like this?

Here’s an alternative What If thought experiment.

Our current democratic structure (liberal representative democracy designed to protect and facilitate bourgeois property rights and order) is intensely hierarchical and centralised. It is predicated on combining consent from the ruled while ensuring continuous rule by elites who will not threaten the core interests of state or business, and explicitly not ‘the mob’. Sovereignty is situated at the top and distributed downwards to lower tiers of the state, if at all. The actual power available to the people is restricted to that of choosing between candidates at elections, and handing over all power to them until the next election.

At the top and centre in the UK is Westminster (ignoring for now the absurd throw back to feudalism that is the unelected House of Lords). Below are national parliaments and assemblies, followed by regional, district or city councils. The last have so little power (both in terms of decision making and financial independence) as to be mere administration arms of national/centralised government. At the very bottom are Community Councils: appendages of local authorities that ‘allow’ pseudo consultation with those who can be bothered to waste their time going to these meetings.

What if…

What if there was a revolution and this structure was revolved and inverted? What if sovereignty was invested in the people at the place where they lived and at a scale that allowed everyone to participate regularly? What if decisions that affected people could be discussed here and real consent created. A federated structure of co-ordinating assemblies of delegates (not representatives) from Community Councils could then allow governance by direct democracy: the administration of things rather than the coercive domination of people. With popular democracy in place we could consign the Palace of Westminster to its proper function, as predicted in News From Nowhere: a dung warehouse. Kakistocracy no more!

Just a thought.

(Maybe leave to another occasion the introduction of democracy to the realm of work)

“What if there was a revolution and this structure was revolved and inverted? What if sovereignty was invested in the people at the place where they lived and at a scale that allowed everyone to participate regularly? What if decisions that affected people could be discussed here and real consent created. A federated structure of co-ordinating assemblies of delegates (not representatives) from Community Councils could then allow governance by direct democracy:”

I think hierarchy has to arise, suppose for example, Yorkshire and Lancashire share a problem but each has a solution unacceptable to the other. In practice you would need a layer above them to find a third solution thus resolving the deadlock. Given humans like power something like the current system would arise naturally.

‘What if…’

Yep, what you describe is the [unionist] principle of subsidiarity, as defined (for example) in Article 5 of the Treaty on European Union. Basically, the principle ensures that decisions are taken as closely as possible to the citizen and are ‘passed up’ to be taken at local, regional, national, or international level only as required by the generality of those directly affected by the decision. Thus a decision that only directly affected a single citizen would be taken by the citizen her/himself, a decision that only directly affected a citizen and her/his neighbours would be taken by the neighbourhood… and so on up to the international level, where decisions that directly affected the entire planet would be taken by world government.

This is also how decision-making within the Universal Church of Rome is supposed to be organised; in fact, this is where the principle originated. Devolution can also be read as an attempt to implement the principle to the UK retrospectively; though it’s been too piecemeal and cack-handed in its implementation to be effective.

The supremacy of the parliaments cannot be disregarded. As long as we have the country being ruled by professional politicians we are unlikely to either reach democratic decisions , or to have an efficiently managed country. Many of our current politicians seem to have never held a real job, that is, one on which their livelihood depended. We also need to consider that the way is wide open for our politicians to be bribed while in office, or by benefits to be received on demitting office. (This could be reduced by requiring that the finances of politicians and their families be open to public inspection, e.g online, but that won’t happen)

It is difficult for the man in the street to become elected, as few people have the private resources to take on the party system that funds most candidates. Moreover, were the man in the street to be elected he would be powerless to accomplish anything, even as the opposition at Holyrood is powerless.

My suggestion would be that all elected representatives should be from the people. Political parties would be barred. Representatives would be sourced from clubs and societies, the grass roots. By lot or by vote. From the Women’s Institutes, from train societies, art clubs, book clubs, yacht clubs and the local Hunt. From Working Men’s clubs, and philosophical societies, and commercial institutes. (Even from those groups who propose bizarre schemes to address “climate change” without considering the more serious and more damaging problems of plastic, overconsumption and waste that we actually could address fairly quickly.)

The Lord’s would be peeled back to hereditary peers, as they are rooted in the land, often literally.

It could not be any worse than what we have now, could it?

The supremacy of the parliaments cannot be disregarded.

No, and it shouldn’t be either. It’s vital to democracy that our popular assemblies remain sovereign in our public decision-making.

The question is how those assemblies are assembled. The beauty of sortition as a method of selection is that it takes control of the selection process out of the hands of party and other private interests and puts it in the hands of blind chance. Basically, we assemble our parliaments and councils periodically as juries, by lottery rather than by election, with every citizen being liable for jury service as a civic duty.

I have said for a long time we should choose our representatives randomly, OK we would have some loonies and crooks and idiots…. Oh Wait.

I also feel that, in order to stop the civil service manipulating policy to make life easier for themselves we need two MPs per constituency elected out of sync so that the more experienced on could mentor the newcomer in how to handle civil servants and the mechanisms of power.

I’ve just seen the website you posted re Citizen’s Assembly. Excellent. Yet I have never heard of it. Not in any newspaper, not in the MSM (not on the BBC!)

Seems sensible. No one glued to the road, I suppose.

How does such a movement build?