Bread, Roses, Coal, Water and the Ecosexual Position

Galen, a physician in ancient Rome, has been credited in attesting that “bread is food for the body, but flowers are food for the mind.” A version of Galen’s claim became a trade unionist call to action and reflection in the early 20th Century. The assertion that there must be “Bread for all, and roses too” was popularised in speeches by North American trade unionist suffragettes, Helen Todd and Rose Schneiderman, poet James Oppenheim, as well as banner slogans and chants from the striking textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts (1912). What may have been lost over time is that the roses stand for wellbeing, beauty and joy. Now, as then, the trade union fight is for the collective improvement in the quality of our lives, one which goes beyond existence and basic subsistence. The collective fight is one of hope, now and in the future.

In 2021, as the bleakness of multiple forms of climate catastrophe and the reality of living through a pandemic unfold, hope is wearing thin. There is a slow recognition that the fossil fuels, nuclear, mining and weapons industries have caused permanent destruction and contamination to land and water across the Earth. The lives which many of us have been so used to knowing and living, rely on the exploitation, displacement and harm of human and non-human lives. In these realities, ways of knowing, and living, seldom recognise the benefits of a nourishing and nourished society, one which sustains collective care, wellbeing and joy, unless presented by institutions and industries interested only in profit.

Despite Western societies becoming richer, the people have become no happier and the causes of anger, dissatisfaction, exhaustion and alienation amongst us are rarely addressed. Every fibre of our being is mechanically processed as payment and/or profit. Our (restricted) movements, be they organised demonstrations of collective disaffection or those movements which require the leaving behind of your sense of belonging, are also sources of profit. Where is our replenishment? Where is our rejuvenation? Where is the re-collection of who we are to each other and what our responsibility is in the world? We keep searching and looking for healing spaces, to keep from being destroyed. Those who are not (yet) dead have to go on. Is it any wonder those who are living are now experiencing grief?

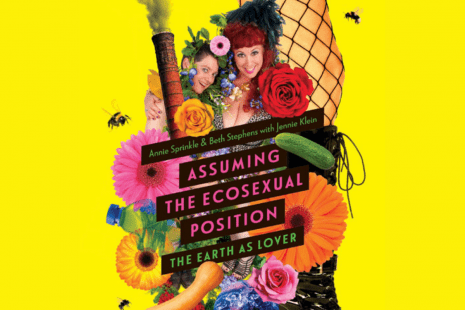

The problem is, if humans become consumed by grief, we lose our ability to experience joy and this drains our capacity to keep fighting for climate, environmental and social justice. Perhaps artists and writers can bring some insights and hope into the picture. When navigating and pushing back against oppressive colonial violence, Cree poet Dr Billy-Ray Belcourt attests that “Joy is art is an ethics of resistance”. And in their latest book, Assuming the Ecosexual Position: The Earth As Lover, Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle draw attention to the practice of Argentinian artist and activist Roberto Jacoby, “who advocated for what he called “strategies of joy”: small actions that face down and confront the fear in people’s minds.”

Photo credit Julian Cash and Design Credit Sandra Friesen

Collaborative environmental activist artists, Professor Beth Stephens and Dr Annie Sprinkle, root their (19 year) relationship with each other, nature and their activist communities in “strategies of joy.” Their current exhibition, Assuming the Ecosexual Position, was featured in Wired Women, Dundee’s NEoN Festival 2021. This exhibition has been shown online (in NEoN’s virtual gallery space) and is currently showing at Sharing Not Hoarding, an established public art site, until January 16th 2022. For many years, NEoN Digital Arts has presented visual art festivals, academic symposia and pop-up art events that are temporarily embedded into Dundee’s city landscape; using locations such as public buildings, shopping malls and gallery spaces.

Photo credit: Kathryn Rattray

The Assuming the Ecosexual Position exhibition, at Sharing Not Hoarding, is a series of 18 large format posters situated on painted wooden hoardings along S Castle Street (near Dundee’s waterfront). These highly colourful exhibition posters are camp and mischievous digital photo collages, packed with innuendo. Along with some newly created works, the posters depict images from Stephens and Sprinkle’s Love Art Laboratory projects, E.A.R.T.H Laboratory (UCSC), theatre shows and films, and their new book, Assuming the Ecosexual Position: The Earth As Lover. They include wedding photos from their marriages to the Sea, the Snow, the Rocks and the Earth, as well as the Ecosexual Manifesto, and a gorgeously illustrated how-to list of 25 Ways to Make Love to The Earth. Since Sharing Not Hoarding is just opposite Dundee Urban Orchard’s Edible Garden, in Slessor Gardens, it is the perfect site for this particular show (though the fruit will be eaten by now). The Assuming the Ecosexual Position posters can be easily viewed from a distance, drawing a broad range of publics who frequent the park. The exhibition can even be seen by the security camera persons, but the primary audience at this site are a mix of passing pedestrians.

Naya Jones and Lioba Hirsch’s intervention, Incontestable: Imagining possibilities through intimate Black geographies posits geography as a (post)colonial discipline, one shaped by what whiteness sees, understands, and relates to Black geographies. Last year, Sekai Machache’s exhibition a BREAdTH apart (part of the Scottish Black Lives Matter Mural Trail) was located at Sharing Not Hoarding. The art show featured 16 portraits of Black people in Scotland wearing facemasks made of African cloth and was created “to bring forward ideas about the visibility of black people in Scotland, and about our vulnerability to Covid-19”. The works also highlighted narratives surrounding Covid-19, which continue the biologising and pathologising of Blackness and race. Shortly after the portraits were put up, they were vandalized. As Jones and Hirsch assert, “anti blackness is incontournable and upholds the resistance–struggle–resilience discourse, which Black knowledge and lives are unable to move beyond, and eventually disappear into”.

Photo credit: Sekai Machache

Like Black geographies, which can offer versatility, creativity, and freedom to present the possibilities of Black life, knowledge production and futures against and beyond resistance to anti blackness, artworks too can become entry points into conversations that some people may have previously felt excluded. Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle use humour and sexy high camp as a hook into what artists Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison call a “conversational drift” where all parties are invited into the conversation to appreciate the whole picture. The inclusive approach of “conversational drift” was especially important when Stephens and Sprinkle made their films Goodbye Gauley Mountain: An Ecosexual Love Story and Water Makes Us Wet: An Ecosexual Adventure. NEoN screened Water Makes Us Wet during the online portion of this year’s festival, followed by a filmmakers Q&A with guest curator Ailie Rutherford.

In Water Makes Us Wet, the artists tour the lakes, rivers, watersheds, ocean beaches and wastewater facilities of California. In addition to showing the work of wildlife biologists who are protecting the water sheds, they highlight the damaging consequences of corporate water extraction and exploitation by Nestlé. Their first collaborative film Goodbye Gauley Mountain also focuses on corporate exploitation and extraction. It became Beth’s PhD project; a personal activist film that exposed the callous ecological devastation occurring in Appalachia. When Beth Stephens was growing up in West Virginia, the Appalachian Mountain range was a pristine and complex ecosystem. However, because of the shift from conventional coal mining to Mountain Top Removal (MTR) (that literally blows up the tops of the mountains to access coal) the aerial photograph of Appalachia now shows a different picture. Trees, plants, water sheds, water supplies and lives are all being ruined to supply cheap energy to the big cities. Goodbye Gauley Mountain concludes with Beth and Annie’s wedding ceremony to the Appalachian Mountains.

Imagine if the Trossachs hills had coal seams running through the summits. Would Scotland have been supplying cheap MTR coal to energy hungry London? What would Glasgow have done for a water supply if Loch Katrine or Loch Lomond had been poisoned from the toxic run-off from the open strip mines on Ben A’an, Ben Ledi and Ben Lomond? If you think that this couldn’t have happened in Scotland, look at the satellite picture of the “House of Water” coal strip/surface mine near Logan, in Ayrshire. When a nation has signed up to Free Trade Agreements like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, now called the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement CUSMA) there is almost no recourse of action against multinational corporations that destroy entire ecosystems like the Appalachian Mountain range. From our perspective in Scotland, we should all be paying attention to the details in the Free Trade Agreements that are being signed in post-Brexit UK. In the latest developments on climate action, it remains to be seen if the new USA – China coal decommissioning agreement at Cop26 will be implemented soon enough to stop further damage to Appalachia.

Technology is often considered a hopeful solution to varying problems, from social justice, our climate crisis and even, the pandemic. However, we are living in an age of complex contradictions. Throughout the pandemic, many people living with disabilities and/or chronic illness gained more access to cultural events, as did people who might not feel comfortable entering and being in arts and cultural centres, museums and theatre spaces. For people with access to the internet, the many (often unnecessary) online meetings facilitated working from home (in some cases providing better working conditions), and even more online meetings facilitated nights-in, quizzes or karaoke to connect with friends and family. For some, it was connecting with strangers to make sense of the pandemic or over (new) shared interests. Whatever the reason – for those who had access – the same technologies (hardware and software), were in our homes, blurring work and personal life. For those who had access and those who didn’t, the same disparities and hostilities found in real life were exacerbated. Promises of a return to a pre-pandemic world include measures such as increased surveillance and personal data sharing. Online and tech companies – like many corporations and indeed, nation states – also have a relentless drive for growth and expansion at any cost.

Big companies have always demanded more and more resources, from minerals and human labour required to make the tech, to vital resources such as our personal data and the water usage required to hold it. For example, when American multinational corporation and technology company, Intel Corporation opened its first factory in Albuquerque in the 1980s, a decade later, it was using three million gallons of water a day for production. In 1995, Intel gave public notice that it planned to purchase water rights 70 miles south of Albuquerque, prohibiting current owners from using surface water. This move would allow Intel to drill their own wells, to obtain a cheaper supply of water and moving water usage from agricultural and municipal use to large scale industrial use. As Elizabeth Martínez writes in De Colores Means All of Us, “the lure, as always, was the promise of jobs, to justify bleeding massive subsidies and natural resources from a poor state”.

A recent report by David Mytton in the npj Clean Water journal, indicates 29.3 billion devices are expected to be online by 2030, up from 18.4 billion in 2018. To reliably support the online services used by these billions of users, data centres have been built around the world to provide the millions of servers they contain with access to power, cooling and internet connectivity, requiring the use of water. The Information Communications Technology (ICT) sector is responsible for some of the largest purchases of renewable energy but, energy consumption is only one aspect of the environmental footprint of ICT, a less well understood factor is water consumption.

Google and Microsoft (despite the latter changing their methodology) have reported increases in the billions, year on year. Amazon does not publish water figures. A medium-sized data centre uses as much water as three average-sized hospitals, or more than two 18-hole golf courses. From the limited statistics available, it is understood that some data centre operators are drawing more than half of their water from sources suitable for humans to drink and cook from (potable water).

As the report concludes, “corporate water stewardship is growing in importance, yet it is difficult to understand the current situation due to the lack of reporting. The entire data centre industry suffers from a lack of transparency. However, they will only report data when their customers ask for it”.

Technology and nature (humans are part of this) are becoming increasingly entangled, and attention should be focused on how these can work in ways which give back. Not giving back for the sake of doing, or rooted in extractivism, but for our collective good.

Returning to “bread and roses”, the collective good must include ways to experience joy and all kinds of sustenance. However, when Assuming the Ecosexual Position, it is important to recognise that this sexy, exuberant joy with(in) nature is not simply a hedonistic hide-out where people can numb themselves and escape from the heavy responsibilities of facing the consequences of climate crisis. On the contrary, it is a state of mind, a way of living and being, that enables people to stay present with grief, loss, fear and accountability rather than living in a state of denial. Or, as Donna Haraway puts it “staying with the trouble”.

Within this frame, when the conventional ways of fighting corporate greed and destruction aren’t working – including strike action – it makes complete sense for artists Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle (or anyone) to marry a mountain range, or a body of water, in a joyous performance art declaration of love with the community of activists who are in the fight with them (and all of us). As the expansion of media and cultural playgrounds for the powerful are built on the riverbanks of Scottish cities, they dutifully play their part in romanticising the abundance and spaciousness of places where hills and glens are found. Both urban and rural areas in Scotland are then marketed by governments and public bodies as sites for private investment, repeating cycles of erasure of ecosystems and ways of knowing and being. Why not then, re-eroticise the universe and call into question the hierarchy of species?

To do anything other, as Katherine McKittrick states in Dear Science and Other Stories, “depicts our presently ecocidal and genocidal world as normal and unalterable’. Our work, she argues, is ‘to notice this logic and breach it”.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by donating today.

Liberal nonsense!

‘Liberal’ is the last thing it is, James. It originates in a synthesis of Marx and Freud, two of the great bêtes noires of liberalism.

The trouble with cut roses is that they often come from Kenya via Amsterdam; sometimes the last bit’s by aeroplane, sometimes by truck. I used to work for a florists’ wholesaler, and remember emergency trips out to Turnhouse on February 13th to collect red roses.

Not quite food miles, but luxury item miles I suppose…

I did have lots of flowers and plants in the house thenabouts; still got the plants.

‘To do anything other [than re-eroticise the universe]… depicts our presently ecocidal and genocidal world as normal and unalterable. Our work… is to notice this logic and breach it.’

Now you’re talking! It’s the hegemony of our existing power relations that make the world normal and unalterable. The historic task of the revolutionary in our present epoch is to subvert this false consciousness by transgressing it in her/his work. Re-eroticisng the universe in one’s work is one way of subverting the present.

The optimistic view of capitalism is that we may use the surplus value it enables us to produce to shape our world in accordance with what Marcuse called in Eros and Civilisation ‘the Life Instincts [‘Eros’], in the concerted struggle against the purveyors of Death’. The pessimistic view is that, in order to accumulate that value in the form of private property, which is essential to capitalism, capitalism represses those instincts and thereby prevents us from creating a fundamentally different non-exploitative world, based on a fundamentally different relation between man and nature (environmental justice) and between man and man (social justice).

I might use my bus pass take a wee jaunt up to Dundee and share a bit of time with Beth and Annie’s work, to see if and how it takes place in the flesh of the world and disrupts the Todestrieb of our present epoch… And treat myself teh tweh brodies, eh plen yen an en ingin yen en a. (There’s nothing more erotic that a Forfar bridie.)

The ecosexual approach appears predicated on the belief that there are hard-to-reach demographics in the climate action debates that have to be appealed to on the basis of “Saving the Planet: what do I get out of it?”, demographic sections which are somehow not included or not invited by mainstream appeals to (for example) placing value on nature for itself. Is there a non-hedonistic aspect I missed?

Anyway, I wonder about the benefits and possible untended side-effects of presenting these choices in way that conflates gratification with duties, and relegates ethical choices to fulfilling contractual obligations. It may just be a silly and light-hearted provocation, but are the underlying assumptions true, and if so, of concern? That is, is such an approach too similar to green capitalism or eco-fashion (apparently eco-glitter is now a thing)? The natural world has never consented to be ravished by humans, and I wonder if imagining these unions is healthy. Rather than reimagining the hierarchy of species, this approach seems to reinforce humanistic supremacy, and such eroticism is just another form of (potentially over-) consumption, hardly a novel observation.

Even more concerning, it appears to stereotype certain demographics as not concerned with nature unless compatible with self-interest, ego or even plain lust.

It’s more about how one orients oneself existentially towards the earth than about having the right beliefs, whether assumes as a basic attitude towards it the reciprocity of a lover, or the dutifulness of a child, or the stewardship of a husband, or whatever, thereby defining the earth as respectively an equal, a master to whom one owes obedience, or a resource to be managed. Ecosexuals orient themselves to the earth as a lover to a lover rather than as a child to a mother or a husband to a resource.

If you follow the reference to Donna Haraway, whom one of the artists, Beth Stephens, explicitly acknowledges as a seminal influence, you’ll find that the exhibition explores how human exceptionalism has been constructed and privileged throughout the history of religion and science, as well as in other secular practices in western culture. On her website, Stephens writes:

“Human exceptionalism, in collaboration with global capitalism, has created the isolated space necessary for the ongoing practices that have produced the dangerously degraded environmental conditions in which we now live. The belief systems and ideologies that allow some people to think that they have the Darwinian survival skill and the rights that accompany those skills to use or destroy other humans and non-humans is now causing the kind of environmental degradation that affects the whole system sooner or later.”

By rejecting or refusing human exceptionalism, ecosexuals seek to rebalance the relationship between themselves and the earth through this reorientation away from both the submissiveness of a child towards ‘Mother Earth’ and the exploitation of the earth as a resource.

Regarding the aesthetic of the exhibition, this also draws on Haraway and, in particular, her narrative of ‘situated knowledges’.

Situated knowledges are the knowledges produced from experience gained on the ground instead of knowledge produced from the privileged heights of the ideologically authorised realms. In originating at ground level, and having not been duly authorised by hegemonic institutions, situated knowledges are marginalised by hegemonic ideology. This is close to Boaventura de Sousa Santos’ narrative of ‘decolonisation’ and ‘cognitive justice’ for the indigenous cultures of the global ‘South’, whose epistemologies run counter to and dissent from the hegemonic epistemology of the European Enlightenment – which I’ve touched on in earlier threads.

Situated knowledge is always partial and always incomplete. Furthermore, it is always on the move. Thinking in terms of situated knowledges erodes what Haraway calls the ‘God’s Eye View’, and this erosion helps begin to level the playing field while making it possible to animate a range of subject positions. It also makes more room for diversity of thought and action.

If you’ve been paying attention to the postmodernism I spout, you’ll recognise Haraway in a lot of it.

(BTW I came up to Dundee today to see the Assuming the Ecosexual Position exhibition. I loved the way it playfully queers and destabilises our ‘normal’ constructions of gender, sex, sexuality, and nature. It was well worth the five hours it took me to get here.)

@Mons Meg, on the topic of water, for example, did the flood-hit people of Germany and Belgium experience that as erotic? Should drought-struck Madagascans be considered involuntarily celibate? Did the record rainfalls in southern India produce orgasms? The ecosexual position, as outlined, seems particularly crass, insensitive, lacking in empathy, redolent of privilege, and several grades down from an appreciation of nature that I would expect in a child starting school. Something for proselytising adults to bear in mind, perhaps, as in this light-hearted cartoon:

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/dec/15/this-christmas-dont-try-to-fix-your-racist-uncle-who-doesnt-believe-in-vaccines-or-climate-change

Also, I fail to see how it in any way eschews human exceptionalism (what other animal has marriages with vows?).

I suppose many people who support rewilding in nature-depleted countries like Scotland would rather humans were kept out of large swathes of nature, perhaps the ecosexual equivalent of the planet keeping its pants on.

I found the exhibition slightly depressing, which is hardly important, but perhaps of more concern is that I don’t see much scope for harmonising the views presented with a more globally-representative movement which values nature for itself. Far from seeing the ‘whole picture’, the approach seems narrow, self-absorbed and small-minded. It is climate science which helps every generation appreciate the biggest picture, with its concepts of deep time and graphical representations of variation across time and space, relating human activity and physical phenomena. Well, perhaps the approach can do some good, if it reaches people resistant to other approaches, introduces the work of scientists, and changes not just minds but behaviour. But perhaps also it could reinforce egoism and shallow appreciation of complex, vital issues.

‘The ecosexual position, as outlined, seems particularly crass, insensitive, lacking in empathy, redolent of privilege, and several grades down from an appreciation of nature that I would expect in a child starting school.’

Well, the orientation of a lover to her/his beloved certainly isn’t for everyone.

And the ecosexual response to signs of the earth’s distress – i.e. with the reciprocity of love rather than sadomasochistically with submissiveness or control – is at least arguably a valid alternative response.

My problem with it is that it’s still anthropomorphic; its ruling metaphor still ‘colonises’ the earth with human qualities by casting it in the role of a lover, no less than does the moral response, which casts it in the role of a dominant ‘master’ who has rights of us, or the managerial response that casts it as a ‘beast’ we must husband or domesticate. And it’s a problem for me because its ruling metaphor thus still speaks of the alienation of ‘man’ and ‘nature’, which is the heart of the matter for Marxians like myself; it’s still an ideology of capitalism.

Anyway: I’m away back for another gander at the exhibition before I catch the first of my two trains and three buses doon hame.

Think I agree with Mon Meg.

I haven’t seen Sprinkles or Stephen’s works or read any of their books (few articles here and there) – but there is always something wrong with whatever becomes the visible narrative and we should critique it!

Their eco-sexuality isn’t the whole scope of eco-sexuality. Respecting and loving the earth is something which has long been done. There will be problems with eco-sexuality (as there is with every ideology) – consent being one and like those SleepingDog has outlined, but as Mon Meg has said, at least an alternative is being posited.

That said, I really enjoyed this co-authored article, more of this please!

@Mons Meg, I don’t see what orientation has to do with any of my comments, which would similarly apply if an artist thought:

“How to reach that difficult-to-persuade gammon demographic?”

and thus the Top Gear World Tour of Climate-Endangered Roads rally challenge roadshow was born. Having not watched the series, I don’t know if its autoerotic presenters employ a similar ‘humour and high camp’ style. No doubt there are some people who would tune in to watch Jeremy Clarkson frolicking naked in a geyser of petroleum; but would they learn anything beneficial about climate change? Would the climate action movement gain from a ‘save our roads’ faction?

And not just anthropomorphic, not just anthropocentric, but without the possibility of building truly common ground, especially if you ignore some drastically divergent life experiences. Such as with water: just ask the people of Bangladesh:

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/12/13/how-bangladeshs-poor-are-paying-the-costs-of-climate-damage

or many other places round the world.

I’m not sure that the artists whose works comprise the exhibition we’re talking about are much concerned with ‘How to reach that difficult-to-persuade gammon demographic?’; as I said, I think they’re more concerned with how they orient themselves existentially towards the earth. Feel free to orient yourself differently.

I’m also less sure than you are that, in giving expression to their own life experiences (‘situational knowledges’) in their exhibitions, film-making, performances, and writing, Beth and Annie are ignoring or denying ‘some drastically divergent life experiences’ of others, such as the situational knowledges of flood-hit Belgians and Germans or those of drought-struck Madagascans.

Have another read at my post of 15th December 2021 at 10:39 pm, which indicates how their ecosexual aesthetic emerges from the decolonisation movement, and tell me why you think they’re so dismissive of those ‘drastically different life experiences’ you allude to?

@Mons Meg, as the kids these days say: “blah, blah, blah”

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/dec/16/good-citizen-award-pontypridd-young-campaigners

There is indeed a populist call for ‘a little less conversation, a little more action’, which call itself stands in need of interrogation.

Such a call still begs the questions: What action? Why this action rather than that? How do we implement this action? …blah, blah, blah.

And, of course, the most important question of all is: Do we have these conversations or do we just defer to the wisdom of some or other demagogue? (And to which demagogue are we to defer those questions?)

@Mons Meg, I can’t help feeling that would make a great speech bubble somewhere, should some graphic artist oblige…

Aye, it would (though it would have to be a gey big speech bubble). More ‘S for Socrates’ than ‘V for Vendetta’.

At the Socrates Sculpture Park on Long Island in New York, there’s not a piece of graphic art but a piece of plastic art that takes the form of a spoke in a wheel and is entitled ‘S for Socrates’, who was forever putting spokes in demagogues’ wheels.

If you ever get the chance, visit the Socrates Sculpture Park (if it’s still there – I visited it 30-odd years ago). It was an abandoned riverside landfill that the local community transformed into an open studio and exhibition space for artists, on the premise that reclamation, revitalisation, and creative expression are essential to the survival, humanity, and improvement of our urban environment… blah, blah, blah. (Though what good this does the flood-hit people of Belgium and Germany or the drought-stricken people of Madagascar I don’t know.)

@SleepingDog

Everyone has a different point of experience, from how we have lived through the pandemic to the every day.

It feels like the authors (and indeed assuming the eco-sexual position people), are putting forward a way for people to enter into a process of de-alienation – seeing (maybe even for the first time) from life forms and experiences outside of their own.

To say that eco-sexuality isn’t for people in Bangladesh, suggests that they haven’t (and don’t) practice eco-sexuality, when perhaps we (people and places completely embedded in capitalism) have chosen to ignore and appropriate these practices to suit our systems.

@Connor Sssssh, to be clear, I mentioned extreme flood events in Bangladesh, Germany and Belgium, extreme rainfall in southern India, and drought in Madagascar, only in the context of the Water theme, and climate change. I did not watch the whole movie Water Makes Us Wet: An Ecosexual Adventure, just the trailer. I do not see how proposing marriage to the Indian Ocean, for example, would be as helpful as building oyster reefs to dampen the kinetic energy of incoming waves. It seems that there could be many serious and scientific points in the movie, but I wonder if the packaging helps get these across. Can we have a selfless, hands-off, tempered joy in nature that is perhaps more enduring, and less like the partying-on-the-Titanic (to use another watery metaphor) that seems too widespread today? On rewilding in the UK:

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/dec/16/chris-packham-meets-crown-estate-to-promote-rewilding-royal-land

This was actually quite good… Will Bella be doing more like this?

Hi Clare – thanks glad you liked it? Do you mean more arts coverage?