Foilles (or, The Free State of Eddrachillis)

Gemma Smith continues her midge-bitten and cleg-infested journey through history and landscape, taking in Coco Channel and Ivan Illich, in a search for the forgotten and the mislaid of the highlands.

Stack Lodge, one of the Duke of Westminster’s numerous holiday homes in the Reay Forest (photo by Gemma Smith)

Foilles is the name of a place that no longer exists, and to be honest I couldn’t with any certainty tell you where it was ever located. Probably coming from the Old Gaelic fòlais/foghlais meaning ‘streamlet, narrows’ – the same word gives us the names of Fowlis Castle near Dundee and Foulis Castle near Evanton – Foilles is first depicted by the cartographer Ortellius in 1573, and appears in a number of forms until Blaeu’s atlas of 1635, after which it abruptly disappears off the map. These representations position Foilles inland from the historic settlement of Laxford (Old Norse lax fjǫrðr ‘salmon fjord’), most likely either at the very west end of Loch More in Eddrachillis, West Sutherland, where Achfary is now, or near Kinloch at its eastern extremity. It is not included in Robert Gordon’s 1636 redux of Pont’s map nor mentioned in his A Genealogical History of the Earldom of Sutherland from Its Origin to the Year 1630 – and you would expect him to know, being the Sutherlands’ official historian. I cannot find reference to Foilles in any other source, and I sometimes wonder if it ever existed at all. I have developed a minor obsession with the place and went looking for it last summer, spending a day walking the length of Loch More from east to west, scanning every hillside for ruins, crop marks, clumps of bracken, any signs of former human habitation, to no real conclusions.

If you take a right turn at Laxford Bridge on your way north from Kylesku – unlike the majority of visitors these days, who stick to the NC500 route – the road that cuts south-east across the county to Lairg follows the waterways down one of the loveliest and loneliest straths in Scotland, along the River Laxford to Loch Stack and then Loch More and the probable location of Foilles. Eddrachillis comes from the Gaelic Eadar-dà-chaolais, ‘between two kyles’, the kyles originally marking the boundaries of the parish being Loch Laxford and Caolas Cumhang, ‘the narrow strait’, also known as Kylesku. The first hill you see is the Paramount-Pictures view of Ben Stack, from the Old Norse stakkr, ‘stack’, with the upturned boat of Arkle, a probable Norse –fjell name that nobody’s quite certain of, coming into view shortly after. There is another Norse name here too, if we look back at Pont’s ca. 1583-96 map, the earliest detailed depiction of this region: Louin Skeggabill, a settlement located at the eastern end of Loch Stack, where there is now nothing but a locked estate hut known as Lone Bothy. The first element lòn is Gaelic for ‘marshy meadow’ and most likely a later addition; Skeggabill, however, is almost undoubtedly Old Norse, with the generic element probably coming from bólstaðr, ‘farmstead’, and the specific element looking like it may come from the word skegg, ‘beard’, perhaps indicating a nickname for a historic inhabitant. Now known as the Reay Forest, this area was to Gaelic speakers the Doire Mòr, or ‘great wood’, a deer forest of many centuries standing.

Lone Bothy, Arkle (photo by Gemma Smith)

I first came down this way after cadging a lift with a friend who was doing some hills in the middle of that weird, feverish, Covid staycation summer of 2020. It was a relief to get off the chaotic NC500 route, and between getting dropped off outside Stack Lodge and a pick-up two days later I barely saw another human soul. In 1628 Charles I made Donald Mackay of Farr the first Lord Reay, and this was his hunting forest. The Reay Forest is now owned by the Grosvenor Estate, the property portfolio of the Duke of Westminster, and is principally managed for fishing and the shooting of deer. The first Duke of Westminster leased the estate from his father-in-law the Duke of Sutherland in 1866, inaugurating the age of the sporting estate in Sutherland, and the second Duke, Hugh Grosvenor, purchased the 100,000-acre property outright for £85,000 at auction in 1919. One of the Duke’s most frequent visitors was his mistress Coco Chanel, whose tastes for tweed and fishing were said to be fostered during her time here. Chanel redesigned the interior of the Duke’s house Rosehall, near Lairg, and designed the tweed that still features in the formal dress of the estate gillies.

I had come here to investigate some interesting place-names in the area, and my first stop was Loch na Seilge, ‘loch of the hunt(ing)’, where I’d earmarked the wee red sandy beach as a camping spot for that night, seeing as there wasn’t much flat ground nearby. There are numerous references to hunting and to taighean seilge or ‘hunting bothies’ in the place-names of the Dòire Mòr, but from the verdant grassy patch around the remains of two structures by the burn, these ruins are more likely to be a shieling site or summer pasture – one hut would have been for sleeping, the other for dairying.

Ruighe Ruadh, ‘russet shieling slope’, from the Ben Stack path (photo by Gemma Smith)

Coming down the path the next morning, I was struck by another shieling site, Ruighe Ruadh, ‘russet shieling slope’ – the name now applied to the patch of green to the west of Stack Lodge, which stands out dramatically among the steep hills around it and the rolling tundra of Lewisian Gneiss and bog known as the Ceathramh Garbh or ‘rough quarter’ to its north. I wondered to which settlement such a luxuriant shieling would have belonged. My destination that day though was a shieling nestled right at the foot of Arkle, Àirigh a’ Bhàird, ‘shieling of the bard’, which may well be connected to the Reay bard Rob Donn. Most famously a drover, subsequently he was employed by the Lords Reay as a forester, which was, according to Angus Mackay’s Book of Mackay, ‘a position which afforded him congenial occupation roaming the mountains of his homeland, and holding close converse with the wild animals of the chase’. This would have been decidedly his turf, and indeed one of his most famous songs is “‘S Trom Leam an Àirigh” (‘sad is the shieling to me’) in which he complains of his former sweethearts marrying other men.

I had intended on camping there, but by mid-July the vegetation was so overgrown it would have been near-impossible to pitch a tent. I wandered back along the path to the Lodge, hoping to find a spot nearby. At Loch Stack, Pont’s map warns of ‘black flies souking mens’ blood’, and there’s actually a Gaelic place-name, Tom nan Cuileag, ‘knoll of the flies’, on the south side of the loch. After my July trip I can confirm that the clegs around here are indeed still a nightmare to this day. At the Lodge I spoke to the only person I met in the two days I spent there, a hiker from the Italian Alps travelling in a small campervan. Attempting to explain my research to him, I reached for a more international term: transhumance. ‘Ah!’ he exclaimed, ‘Transumanza!’ They do something very similar where he came from. He looked around himself as if seeing the landscape anew. ‘Of course,’ he said, ‘and the land would have been in much better condition when it was grazed.’

I carried on past the Lodge, through their pine plantation, and across the River Laxford, where I decided to camp the night by the estate’s rather lovely wee fishing bothy. It was a novelty to have a bench to sit and cook on, and the breeze mostly kept the midges at bay. In fact I spent much of the remainder of my trip sat outside that bothy, getting up again the next day to eat breakfast and lunch at the same spot, transfixed by the ever-changing views of Ben Stack to my right and Arkle to my left. Time passed. My lift texted to offer an early pick-up; I declined. I couldn’t move yet. This happens sometimes, in certain places – a feeling I’m sure is familiar to anyone who has spent time walking in the more de-peopled areas of the Scottish Highlands such as Sutherland. It is similar to what the late Irish philosopher John Moriarty was talking about when he said that sometimes you just ‘walk into the sadness that’s in the land’. You become hypnotised, fixed to the spot, until the place has finished telling you what it needs to say. You listen to the rocks and find yourself overwhelmed by the feeling: there was life here, once.

The estate fishing bothy at Stack Lodge (photo by Gemma Smith)

When I got back within signal range, the first thing I did was check the older maps on the NLS website, and there it was, on William Roy’s Military Survey map of 1747: ‘Riroy’, our Ruighe Ruadh, which from the place-name clearly started as a shieling, but is depicted by that time as a major settlement in the area, with several houses and significant patches of cultivated ground along the banks of the river. It also appears as ‘Reroy’ in John Thomson’s 1832 Atlas of Scotland – the same year the strath was cleared in its entirety by the Sutherland estate. Aside from these maps and a few early documents, there doesn’t seem to be much in the way of detailed records of the pre-Clearance settlements of Eddrachillis – at least nothing that lists every township in the way they do for other parishes such as Assynt.

I looked to the Old Statistical Account of 1793 to see if it provided any clues, and happened upon a detail that only raised more questions. Says the Reverend Alexander Falconer in his description of the parish:

‘Who the earliest inhabitants of Edderachylis have been, is now not easily discoverable. After the most diligent inquiry among the oldest and most intelligent people, all that can be learned is, that two or three centuries ago this place was but thinly inhabited; and that the inhabitants were such as held their possessions by no legal tenure, paid no rent, and acknowledged no landlord or superior…’

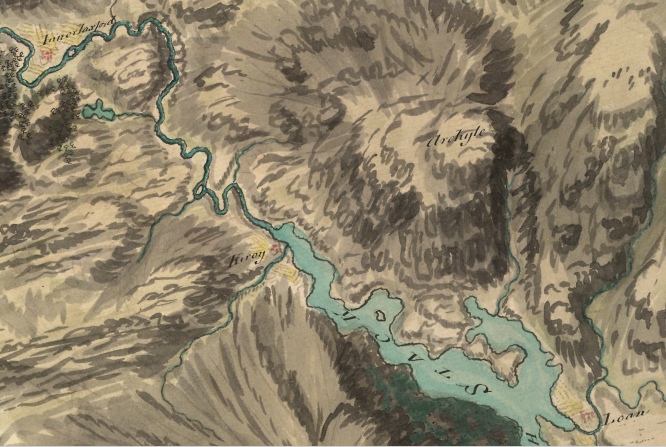

Innerlaxford (Laxford Bridge), Riroy (Ruighe Ruadh) and Loan (Lone), on Roy’s military map of 1747

If the OSA was the only source for this there would be no reason to give it any great credence, but this notion is supported by the evidence of the estate’s own accounts. In his 1820 Account of the Improvements on the Estates, in which he described the motivation behind the Clearances as being to improve ‘the industry’ of estates in Sutherlandshire in such a way that they would contribute ‘to the wealth of the empire’, James Loch, Chief Agent to the Marquis of Stafford and later to the Duke and Duchess of Sutherland, says that when auditing Poor Relief on his arrival in the region:

‘It appeared that a very numerous body had fixed themselves in the more remote districts of the estate, and on the outskirts of the more distant towns, who held neither of landlord nor of any of the tacksmen; and who, in short, enjoyed the benefit of residing upon the property without paying any rent whatever. Their numbers amounted to no less than FOUR HUNDRED AND EIGHT FAMILIES, Consisting of nearly TWO THOUSAND individuals.’

The capitals are his own here, and with good reason – at that time this would have amounted to almost an entire parish’s worth of people. Furthermore, Sir William Fraser’s The Sutherland Book, a collection of estate papers, tells of John, ninth Earl of Sutherland, whose contemporary Robert Gordon rather uncharitably described him as ‘weak of judgement, deprived of natural witt and understanding, being able to governe neither himself nor others.’ During his time the administration of the earldom was overseen by his sister Elizabeth and her husband Adam Gordon, and from 1509 to 1512 was actually handled on behalf of the Crown by Andrew Stewart, Bishop of Caithness, who was at that time High Treasurer and Chamberlain of Sutherland. The majority of his accounts submitted to the Exchequer still survive, giving us an unusually detailed idea of the extent of the Earl’s possessions. As we are told:

‘They are divided into two classes, property lands, or those held by the earl, and tenandry lands held by his tacksmen or free tenants […] which included Edderachills, and [Glen]Coul in Assynt, with a large portion of the present parishes of Clyne and Rogart.’

The free tenants listed are high-status individuals of the likes of the Chief of Mackay, and it is entirely possible that historically they could have passed on these benefits to their people. This seems to be a manifestation of the original, Gaelic customary law of dùthchas, in this context, a right to the land not subject to tenure, lease or rent. In his article ‘The Invention of the Crofting Community’, Iain Mackinnon has written about how the term ‘crofter’ is a foreign and post-improvement imposition, with the people describing themselves instead as Gàidheil or as tuatha, which was often rendered ‘tenant’ or ‘tenantry’ in translation. Tuath can mean both ‘people’ and ‘land’, illustrating how the two things were intrinsically linked.

This may well be what the Sutherlands’ agent James Loch was referring to when he made his famous statement about the people of Sutherland, declaring that ‘no country of Europe at any period of its history, ever presented more formidable obstacles to the improvement of a people arising out of the prejudices and feelings of the people themselves.’ He goes on to lament the condition of the tacksman [the middling tenants], whom he characterises as existing in ‘a state of idle independence, in habits almost of equality with his chief…’

A couple of pages later, Loch says: ‘So strong, however, were the prejudices of the people, that, even to those who were subjected to the power and control of the tacksmen, this mode of life had charms which attached them strongly to it.’ The italics here are my own – even those who were subjected to the power and control of the tacksmen, suggesting not everyone was – and then:

‘Like all mountaineers, accustomed to a life of irregular exertion, with intervals of sloth, they were attached with a degree of enthusiasm, only felt by the natives of a poor country, to their own glen and mountainside, adhering in the strongest manner to the habits and homes of their fathers. They deemed no comfort worth the possessing, which was to be purchased at the price of regular industry; no improvement worthy of adoption, if it was to be obtained at the expense of sacrificing the customs, or leaving the homes of their ancestors.’

Loch’s view was shared by Elizabeth, Countess of Sutherland, who complains in a letter to a friend in 1799 that, ‘This country is an object of curiosity at present, from being quite a wild corner inhabited by an infinite multitude roaming at large in the old way, despising all barriers and all regulations.’ Whilst these all may be standard reasons given for justifying Improvement, both their comments suggest that the situation in Sutherland was one that they found especially objectionable.

A plaque at Achfary pays tribute to the employment and ‘comfort’ the Westminsters’ tenure brought to the region (photo by Gemma Smith)

I had already planned to examine the landscape of the Reay Forest or the Doire Mòr using the anarchist thinker Ivan Illich’s conviviality theory, so this all worked out rather well. Aside from any matters of free tenantry, the toponymic evidence presents a picture of a historically convivial landscape, far removed from the rather desolate place we see today. Illich defined conviviality as ‘autonomous and creative intercourse among persons, and the intercourse of persons with their environment’, where ‘intercourse’ refers to intense and wide-ranging interaction and engagement. It allows for competition, tension and conflict as well as symbiosis and collaboration, stressing the entanglement of culture and environment, human and non-human. Conviviality is a deep and sensory engagement with the world that works towards the continuance of the cycles of matter, nutrients and life.

The Rev Falconer’s comments in the OSA attest to social conviviality in Eddrachillis. Speaking of the inhabitants, he says, ‘Their character for peaceableness, and their harmony among themselves, is uncommon. For the last 20 years and more, scarce one instance has happened of any quarrel or fight among them, or so much as any of them receiving any bodily hurt from another.’ It sounds as though there was little reason for dispute. As he also tells us:

‘Notwithstanding the ruggedness of the ground, and the wild appearance of this country, scarce any place affords a more commodious habitation to poor people, if there are any such in it. [On even the smallest farm] many families want none of the neccessaries of life; having bread and potatoes, fish and some flesh, wool and clothing, milk, butter and cheese, all the fruit of their own industry, and the produce of their farms… when one has occasion to come to it, and remain there, he will find it as convenient for the purposes of living as most parts of the Highlands.’

The estate’s barn at Lone, where they established a cattle ranch on the site of the cleared settlement; Ben Stack in the background (photo by Gemma Smith)

He also attests, over a century on from Rob Donn, that there are ‘several poets in this parish, whose compositions, mostly of the lyric kind, have been admired by good judges, and have shown them to be possessed of uncommon parts and genius.’ And speaking of Tools For Conviviality, Falconer also includes what can only be described as an ode to the humble cas-chròm or foot-plough, still to this day the most sophisticated and effective tool ever invented for working the rocky, uneven land of North West Sutherland, the use of which he credits with greater crop yields. This rather contradicts the supposedly miserable state in which Loch claims to have found the people. The toponymic record points also towards ecological conviviality, with the creatures evidenced in the place-names of the Reay Forest reflecting the historic biodiversity of the area, most vividly described by Robert Gordon in his 17th-century history of Sutherland.

‘Rid deer and roes, wolfs, foxes, wild cats, brocks, squirrels, whitrets, weasels, otters, martins, hares and fumerts […] partridges, plovers, caper-caills, black cock, moor fowl, heath hen, tarmakins, swans, benters, turtle doves, stears or sterling, lair-fligh or knag, which is a bird like a parrot that makes her nest with her bill in the oak tree, duck, drake, widgeon, teal, wild goose, rein goose, roe, whicaps, woodcock, lark, sparrows, snipes, black birds or oisles, mavises or thrush, and all other wild fowl and birds.’

Ultimately, although this place was for many centuries a deer forest and hunting ground, this designation did not always exclude people or indicate a place set apart. As well as evidence of animals, birds, insects, plants and woodlands, the toponymic landscape shows settlements, shielings, and hunting bothies, and marks the passes, ways and fords that people used to move around this mountainous region. This was not a pristine and untouched ecosystem, nor was it the preserve of rich men who kill for fun. For the hisitoric inhabitants of the Reay Forest, to quote the American poet and environmental activist Gary Snyder, nature was not a place to visit – it was home.

Not a shieling – the ruin at Bealach nam Fiann (photo by Gemma Smith)

The last time I visited the Reay Forest was only a couple of weeks ago, when I walked across the Eddrachillis interior on the path that runs from Kylestrome to Achfary. I camped the unusually calm night at a place 400 metres above the strath called Bealach nam Fiann, my tent tucked behind a ruin that the OS Explorer map claims is a shieling hut. There is no water source nearby nor any pasture to speak of; the surrounding ground is like the surface of the moon. On one of the ruin’s bricks is carved the legend ‘E GAME 1932/33’ – this rectangular structure at a particularly exposed spot was probably a later hunting shelter. I imagine the ruin has been conflated with local oral histories of there once having been shielings up in the hills here, which I think were most likely by Loch an Leathaid Bhuain, ‘loch of the lasting slope’, overlooked by Beinn a’ Ghrianain, ‘mountain of the sunny spot’, slightly further south. Bealach nam Fiann means ‘pass of the Fianna’, Fenian place-names being closely associated with sites of geological drama. The view from here is extraordinary, taking in the distinctive peaks of Ben Stack, Arkle, Foinavon and Meall Horn to the north, and the mighty Quinag – Gaelic A’ Chuinneag, ‘the milk pail’ – to the south. This pass was the road to the shieling for the people who perhaps saw their legendary heroes asleep in the mountains around them.

Foilles is still out there, somewhere, buried in the landscape of the Doire Mòr. To find it again, we don’t need to look for it. We need to build it.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

Lovely descriptions which leave those of us who only travel through that landscape on tarmac feeling bereft

What a fabulous article. The knowledge and understanding of the author flow beautifully from the words and I want to know more.

I confess that I’m ambivalent at best on teaching Gaelic as a language to be spoken, but I am very much in favour of teaching Gaelic and old Norse as a means to understand the landscape, its structure and the history of our localities, much as we might be taught Latin and Greek to understand the structures of English.

Great ! More please.

What an excellent account of a determined toponymic explorer.

It is a well worthy project to exhume the possible former social and cultural realities of the lost and large forgotten folk for whom this now ’empty’ landscape was their world, their all.

I commend the exploration, and the openness to taking time to listen to what the place may say to us when we turn away from the distractions and limitations of the present order; when we can be still in those empty spaces. We need those place names; we need that wisdom and that conviviality:

“‘Their character for peaceableness, and their harmony among themselves, is uncommon. For the last 20 years and more, scarce one instance has happened of any quarrel or fight among them, or so much as any of them receiving any bodily hurt from another.’”

This is breathtaking writing. I have read it twice and sent it to many friends.

Such a beautiful piece of writing – I first came to Scotland from New York in 1984, by accident, and ended up in Badcall for a few weeks after a few days in a squat in London, and only later travelled through Scotland . So my introduction to Scotland had little to do with tourism, but my knowledge gap is still extensive, as I’ve had little opportunity to travel back to Sutherland, or elsewhere, in the past years from where I’m now living in the w of Scotland. (Not having money is a very effective damper on your carbon footprint!) I’m intrigued by the description ‘lair-fligh or knag, which is a bird like a parrot that makes her nest with her bill in the oak tree’ – probably not a puffin, could it have been a red-headed woodpecker? Sort of parroty-looking. Such an amazing depiction of Eddrachillis and environs – the description of a society depending on ‘conviviality’ as a possibility is beautiful, as manifested in a Highland hamlet. A dream? Well, yes. A possibility? As climate change encroaches, it might be the only solution for many scattered communities, worldwide.

It sounds like the biggest crime of the indigenous people of Eddrachillis, in the eyes of the would-be “improvers” was their contentment and self-sufficiency. That, and their disinterest in “monetising” their homeland.

What is it about happy, resilient populations living within nature that so enrages the capitalist?

This is a beautiful piece of geopoetic and geopolitical writing from Gemma, about a social class that still controls so much of the wealth of Britain and in most cases, with little intention to let that change. Landed indiduals often say to me, “You can’t keep looking back, you’ve got to move on.” Aye, right, with what was stolen from the vanquished left in the hands of the heirs to the 3 I’s of colonialism – imperial, internal and least recognised but most important psychologically and spiritually, inner colonisers.

This quote (taken from above) from James Loch, the factor (or legal agent) of the Sutherland/Westminster aristocrats, tells all we need to know about a soul hollowed out by violence, unaccountable power and money. It points to the people-place disconnection that has become so normalised in modernity that most folks hardly know the ache that’s there, yet its legacy (I believe) plays out in wider social dysfunctionality.

‘Like all mountaineers, accustomed to a life of irregular exertion, with intervals of sloth, they were attached with a degree of enthusiasm, only felt by the natives of a poor country, to their own glen and mountainside, adhering in the strongest manner to the habits and homes of their fathers. They deemed no comfort worth the possessing, which was to be purchased at the price of regular industry; no improvement worthy of adoption, if it was to be obtained at the expense of sacrificing the customs, or leaving the homes of their ancestors.’