Digging Deeper on Scottish Independence and Scotland’s Future

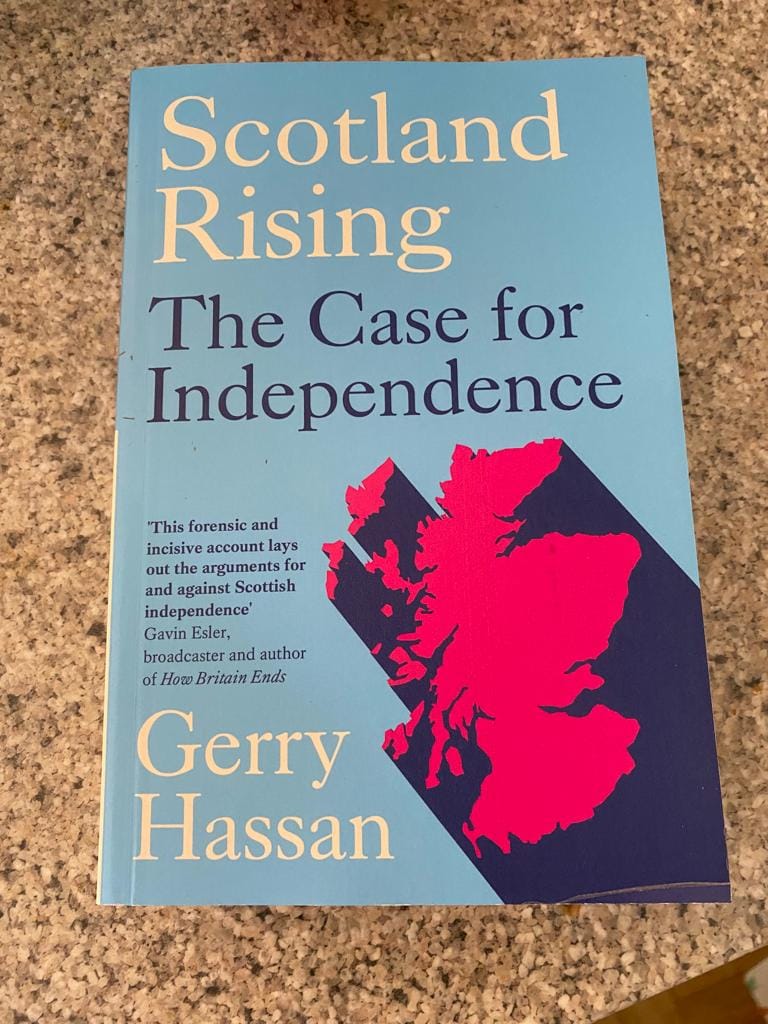

Gerry Hassan, Scotland Rising: The Case for Independence, Pluto Press 2022. Review by Ben Jackson

Gerry Hassan, Scotland Rising: The Case for Independence, Pluto Press 2022. Review by Ben Jackson

It is a curious fact about the history of Scottish nationalism that there are only a few book-length statements of support for Scottish independence. This partly reflects how recently independence has become a closely contested social goal. And it presumably also indicates that, in the internet era, books have been side-lined as vehicles of political debate in favour of the wider impact that can be achieved through online publication or social media. But some advantages of books remain perennial: they offer greater depth in argument and pursue more subtle aspects of an issue, unconstrained by the need for noisy online polemics. There have been some important recent volumes that have done just that. Stephen Maxwell wrote Arguing for Independence (2012), which gave a lucid and judicious statement of the case for a new Scottish state. Maxwell’s book was subsequently flanked from the left by James Foley and Pete Ramand’s Yes: The Radical Case for Independence (2014), which provided a lively socialist perspective on the imminent 2014 referendum. But a lot has happened since then.

There is scope for a fresh analysis of Scottish independence that can take the discussion beyond the ritualistic exchanges that regularly feature in the Scottish and British media. Gerry Hassan has stepped into this gap with Scotland Rising, a book that provides a wide-ranging and thoughtful exploration of the debate about Scottish independence. It is a work that can usefully serve both as a starting point for newcomers and as a stimulus for further discussion for hardened veterans of Scotland’s constitutional debate.

As readers of Bella Caledonia will be aware, Hassan is an important contributor to Scottish public life. An indefatigable writer, editor, and convener, Hassan’s work has tracked the rapidly changing tides of Scottish politics since devolution. Originally closer to Labour’s devolutionist wing than to the SNP, his early writings focused on the new possibilities in Scottish political culture opened up by the advent of the Scottish Parliament, editing books with titles such as A Guide to the Scottish Parliament (1999); A Different Future: A Moderniser’s Guide to Scotland (1999); and The New Scottish Politics (2000). Yet Hassan became increasingly distant from the style of politics practiced by Scottish Labour and a perceptive analyst of the structural weaknesses that were accumulating beneath the seemingly all-conquering Labour machine. Co-writing with Eric Shaw, Hassan’s The Strange Death of Labour Scotland (2012) was one of the first works to perceive that Scottish Labour was heading towards a dramatic electoral reckoning and remains an authoritative account of the crumbling of ‘Labour Scotland’.

Like others on the left of Scottish politics, by this time Hassan had become more sympathetic to the project of Scottish independence. He also recognised that the SNP had been more politically influential (and tactically sophisticated) than figures in Labour and the Conservatives liked to believe. Accordingly, Hassan argued that the SNP deserved a more careful analysis than was to be found in the knockabout political rhetoric of the party’s political opponents, editing The Modern SNP (2009) and (with James Mitchell) Scottish National Party Leaders (2016).

But perhaps the most distinctive feature of Hassan’s work is that he has combined an unabashed enthusiasm for the cause of Scottish self-determination with a pungent critique of the myths that have grown up in Scottish political discourse about Scotland’s purported radicalism and communitarianism. In Caledonian Dreaming and Independence of the Scottish Mind (both 2014), Hassan applied a sceptical gaze to the narratives that have been woven around Scotland’s recent history. Rather than accepting at face value the self-image of Scotland as a progressive, left-leaning nation, Hassan examined the way in which this story had been constructed by elite actors in Scottish civil society. Hassan made the important historical point that, even by the late twentieth century, Scotland remained a rather conservative society, still working through the legacy of religious tensions and a censorious, at times even authoritarian, dominant social morality.

Hassan maintains this emphasis in Scotland Rising. Indeed, what makes Scotland Rising an unusual book is that it outlines a case for independence while maintaining a critical distance from some of the cliches about the distinctiveness of Scottish political culture. It is a refreshingly non-sectarian work. Hassan maintains an open, self-critical tone and acknowledges the force of the case advanced by the other side of the argument.

The independence movement does not always excel at striking such a posture, so on those grounds alone Scotland Rising is a welcome contribution to the debate on Scotland’s future. Although true believers in the cause will find plenty in the book to reaffirm their commitment, Hassan’s real aim is to persuade those who do not yet support Scottish independence to take the plunge. He provides an eloquent account of Scottish statehood as a means of advancing democratic self-government (especially when contrasted with the deficiencies of the UK constitution); of creating a more egalitarian society and economy; of playing a more constructive role in international affairs; and of encouraging a culture of greater responsibility and democratic participation within Scottish society.

Hassan also writes wisely about the historical context of the current debate on independence and about the mechanics of how a referendum might come about. He is confident that a new referendum would be hard for the UK government to resist were there to be strong majority support for holding one within Scotland. He is clear-eyed that such conditions do not yet exist.

The book also illustrates some of the work to be done on the case for independence. As Hassan shows, the democratic arguments for Scottish independence remain robust, in the sense that the claim that a Scottish government and constitution should reflect the democratic preferences of the Scottish people is a difficult point to counter and has gained added salience in the wake of Brexit. But the economic arguments are trickier to land, as they were in 2014. Hassan is right to view the economics of independence more broadly than in much of the media coverage by highlighting deficiencies in the economic record of the UK. In doing so, he tries to avoid getting ensnared in the vexed debates about the specifics of how an independent Scotland’s economy would be run.

I understand why Hassan felt there were diminishing returns from addressing these debates, but there are certain questions about the economy that will eventually need clear answers if undecided voters are to be won over to independence. The recent turmoil in financial markets caused by the UK government underlines the importance of clarifying in advance how a new, smaller state would establish its credibility with investors. How would such a state be perceived if it didn’t have its own currency and was reliant on another state’s central bank to set interest rates? What sort of fiscal policy and level of debt would command market confidence? How much space would there in fact be for more expansive public spending, of the sort that independence supporters expect?

The economics of independence may also take on a new aspect if the political context changes. Like the wider movement, Hassan’s book is left-facing in that it seeks to mobilise the goals of the left for the cause of independence and proceeds on the assumption that the UK in its current form is irredeemably conservative. What if the current opinion polls prove to be correct and we are now heading towards a Labour government with a decent majority, committed to some striking new measures of social investment and further political decentralisation? How should supporters of independence frame their arguments in that case?

All of this is for the future. We can be sure that Gerry Hassan will be at the forefront of analysing these questions in the years to come. But for now, Scotland Rising is an indispensable guide to the current state of the independence debate and it deserves to be widely read and discussed.

Scotland Rising: The Case for Independence can be bought here: https://www.plutobooks.com/9780745347264/scotland-rising/

Yep, it’s refreshingly free of the ridiculous polemic that infantilises so much of the independence debate. It also broadens that debate into a more general one about Scotland’s future. I’m enjoying it immensely. And it’s only a tenner to download in electronic form!

“What if the current opinion polls prove to be correct and we are now heading towards a Labour government with a decent majority, committed to some striking new measures of social investment and further political decentralisation? How should supporters of independence frame their arguments in that case?”

A Labour government with Keir Starmer as PM. The man who has broken all of his election pledges since being elected as leader. Who is openly attacking the Left inside the Labour Party? What chance is there of further decentralisation? Of any striking new measures from someone who bans his front bench from the picket line? I don’t expect any kind of radical change from that quarter.

Yes, but the point is that he isn’t a Tory, and a major selling-point for independence over the past 12 years is the ‘negative’ case that bailing the UK is the only way we can liberate ourselves from perpetual Tory government. The prospect of a Labour government rather spoils that negative case for independence.

…but like night follows day we all know that , eventually ,The Tories WILL regain power from its English base .

Then what ?

Another decade of Austerity that WE didn’t vote for ?

Another decade of being marginalised by a London-centric administration ?

Another decade of even more Devolved powers being eroded OR the dissolution of all devolved assemblies ?

A Labour victory in the next election is only a finger in the dyke temporarily plugging the inevitable flood of Tory control in the near future .

But wouldn’t it be healthier to be voting positively, for something, rather than negatively, as a way of escaping the Tories? Is such negative marketing the best strategy for selling ‘independence’ to the Scottish electorate?

In any case: some pundits are spinning this not as a temporary setback for the Tories but as the beginning of a permanent disintegration or tearing apart of the Tory Party.

Either way, perhaps the cause of independence requires a new marketing strategy.

I cannot think of a single argument for Scottish independence that is any less valid due to the election in England of a party who regularly denigrate and refuse to accept the democratic wishes of the people of Scotland (I mean, of course, in the sense that the SNP are regularly voted in as the largest party in the Scottish Parliament.)

But it’s the job of any opposition party to denigrate and otherwise subvert the party of government and its policies. I wouldn’t expect the Labour Party to do anything less in Scotland.

Hmm… slightly disingenuous, I feel. We’re not talking about potholes or tax rates here. Still, they should keep it up, then when one becomes none, still blame “that semempee” rather than look at themselves. I was a member, twice, back in the day, when they were very different from the Tories, unlike now.

+It is

It is disappointing that a book, particularly a left-facing book, which attempts to persuade people to support Scottish independence shies away from a serious discussion of the economics of an independent Scotland. In the 2014 referendum campaign, the economy was the issue that the NO campaign wanted to keep at the centre of the debate. When the votes were counted it was clear that the campaign for independence had been lost because prosperous areas had voted 60-40 against independence.

In his book, Gerry Hassan makes the point that Scotland is a wealthy country but also an unequal one. However, there is little analysis of how this has come about and is maintained. There is reference to landowners and the ‘super rich’ but little to the property-rich and pension-rich middle class whose commitment to the status quo – both economic and constitutional – is at the heart of Scotland’s inequality.

Good point. The ‘Middle Scotland’ that the Scottish government needs to keep sweet/avoid scaring if it’s ever going to achieve its independence by democratic means.