Is Ireland’s greatest treasure actually Scottish?

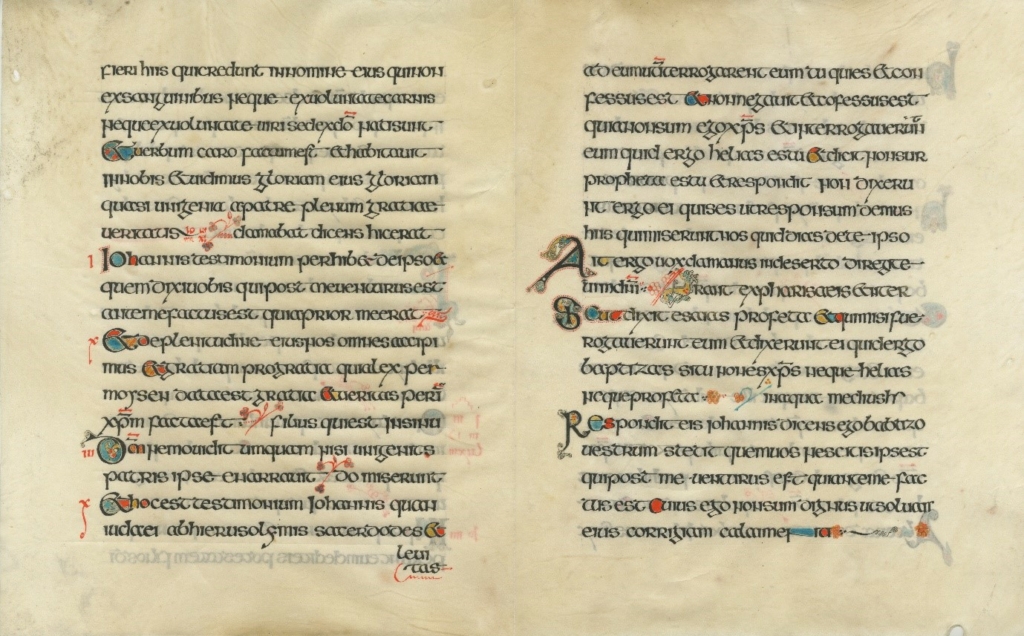

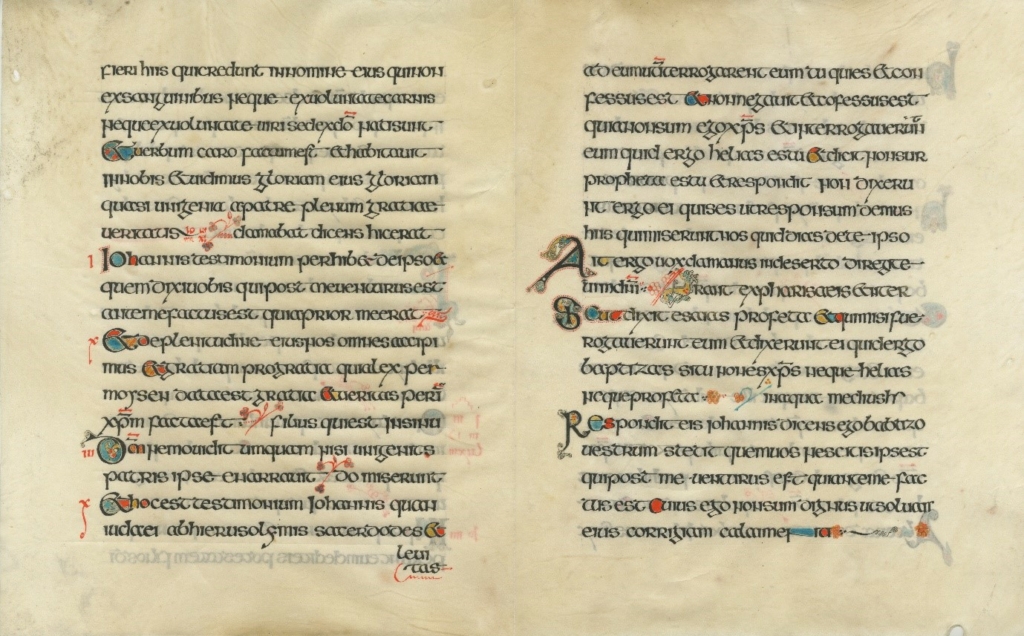

I’m talking about the Book of Kells, arguably the world’s greatest medieval artefact currently residing at Trinity College Dublin and the question isn’t that controversial. Even the standard story of the books production suggests it was begun on Iona at the Monastery of Saint Columba in the late 7th century before being moved to the safety of Kells in Ireland to escape the Vikings. But what if it was actually Pictish and from the Highlands, with archaeological evidence of its production, a Viking attack and even traces of the story of two great scribes collaborating on the book, with one struggling on alone into old age to get it finished? It all sounds a bit too Hollywood, but when you take recent archaeological discoveries and evidence within the Book of Kells itself and put them together it makes a compelling case.

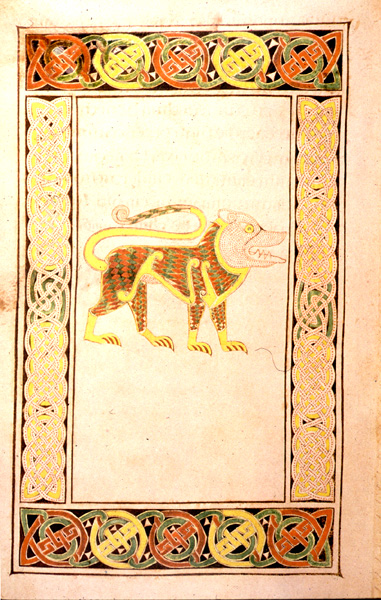

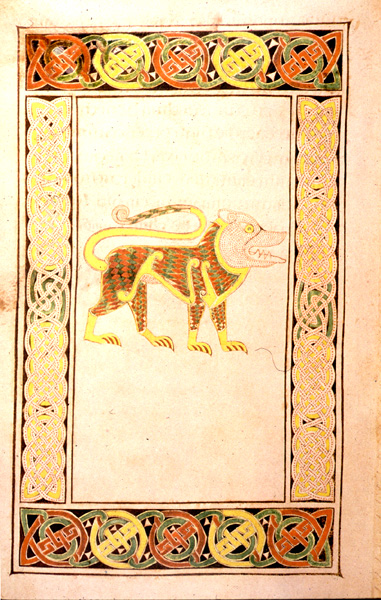

Recent work by the art historian Dr. Victoria Whitworth makes a convincing argument for the Pictish origin of the Book of Kells. It is after all packed with Pictish style animals, which are not easy to imitate accurately as can be seen from the attempt at this lion by the scribe of the Book of Durrow, a 7th century Irish gospel Book. Using spirals to delineate muscle tone is one of the key features of the Pictish school, it does get copied, but not often well.

Image credit: Inverness Museum and Art Gallery

When compared against a ‘real’ Pictish wolf, this lion doesn’t quite have the same elegance, in particular the spirals are not used to good effect to harmonise the legs and body.

Style alone is circumstantial but making a Book in the early medieval period is a big operation that will leave evidence. The main industrial process required for Book production is that of parchment making, calf hide being the medieval paper of the day. To make parchment lots of lime and good weather are ideal, it’s a Mediterranean craft that Ireland, with it’s mild winters and vast quantities of limestone could just about adapt to. The North East Highlands, with harsh winters and no access to limestone is not the place to look for a parchment making workshop.

But you can’t argue with the evidence. In the mid 1990’s after a promising crop mark revealed a tell-tale boundary ditch, an excavation lead by Martin Carver from York University began in the village of Portmahomack on the Easter Ross Peninsula. It soon became clear that it was the site of an early Pictish monastery and eventually the complex workshop enclosure, with pits, bone pegs and curved blades was deciphered, it was a parchmanarie. This isn’t just unusual, it is unique, no other parchmanaries have ever been discovered. And it had a few lessons in store for the modern parchment maker, they weren’t using lime to soak the hides, they used seaweed ash instead. Also the lunellum, the curved blade used to scrape the hide was tiny, much smaller than a modern equivalent. This is because they were using hot water to strip unwanted layers of membrane from the hide, a much more efficient method than brute force alone.

Parchment making area and the toolkit recovered from the site.

There was also a metal workshop with evidence of craftsmanship of the highest quality including a metal boss thought to be made by the same craftsman that produced another Irish treasure, the Derrynaflann silver paten. A stylus was also recovered and a book clasp as well as fragments of high quality Pictish sculpture including one with a written inscription. You could not hope for a better range of finds to support the theory that the Book of Kells could have been made at this site. One more crucial detail emerged later, once all the post holes and structures had been documented. The entire site was laid out geometrically, some of it even in the Fibonacci sequence, these craftsmen shared the same obsession with geometric detail as found in the great insular gospel books.

Another dimension to this is how close recent research can bring us to the inhabitants of the Portmahomack Monastery and to the creators of the Book of Kells. Palaeographer, Dr. Donncha Macgabhann has analysed Kells in minute detail and concluded that it is the work of 2 individuals, the master artist and the scribe artist, collaborating on an initial campaign before a break in the work for an unknown reason. Later the scribe artist returns to finish the work alone but this time impaired in some way, possibly much older and loosing his abilities, maybe even suffering from dementia as there are numerous confused additions in the final phase of artwork. Add this to the skeletal evidence from Portmahomack and an incredibly personal account of the monastic experience is revealed. Numerous strain injuries from the heavy workload, violent deaths and serious injuries that were survived, possibly at the hands of the Vikings, to the absence of fish in the diet and the remnants of a snack, roast hazel shells round the hearth.

This is a fascinating story, but does it really matter that Scotland doesn’t have any of the manuscripts created here during the golden age of Saints and Scholars in which the Gaels where the intellectual elite of Europe? Yes, because the insular monks weren’t just engaged in high-end colouring in, they were crucial to the emergence of Western civilisation after the fall of Rome. Charlemagne takes a lot of credit for getting Europe sorted out in the 8th century, but if we look at who he employs to get the job done, it’s monks from Columban foundations. Even the famous Carolingian calligraphy script is pinched from a daughter house of Luxeiul Abbey in France, set up by Irish monk Columbanus in 590. If it wasn’t for these pioneers of literacy beyond the Roman frontier we’dallbewritinglikethis, word division was their idea, or we would still read only in Latin, verbum sic, using the Roman alphabet to record languages beyond Latin was also their innovation.

In Ireland, this all gets a mention, and rightly so. But over here, our wealth of stone artefacts from the period, Pictish symbol stones in particular skew the perception towards an enigmatic and allegedly illiterate tribe. The later marginalisation of the Gaelic language and the loss of its intellectual elite has left it on the fringes in Scotland. Even with increased state support only 1.1% of the Scottish population can speak Gaelic. (1) Compare that to the 39.8% of the Irish population that can speak Irish.(2) Of course, the reasons behind this are complex and the Irish language is by no means secure despite its relatively impressive state support.

One aspect that clearly divides the approach of Scotland and Ireland however is the difference in status and visibility given to the same heritage. You cannot interact with civil society in Ireland without seeing the Irish language and the descendants of its calligraphic scripts on everything from Post offices to pubs. No tourist could possibly enter the country without being bombarded with Book of Kells imagery and merchandise, this element has probably gone too far, Book of Kells pyjamas, seriously? One factor underpinning this confident cultural identity is surely the overwhelming evidence, Ireland is not short of medieval manuscripts. They are still turning up, demonstrating a rich and ancient culture confident with its own language and culture as well as Latin and Greek.

There are many in Ireland who question the value of the Irish language but no one is denying its rich history, that would be futile in the face of overwhelming evidence. However, in Glasgow it’s not uncommon for critics of Gaelic to state that the area has no history of the language. Academics can refute that claim with sound evidence, numerous placenames and a royal document from 1180 referring to a Gaelic family in the area, but this sort of evidence only convinces those that want to listen. The heavy lifting of culture is done by its art and in this respect the Scottish Gael is at a serious disadvantage in our image drenched society. All the breath-taking, world famous and highly lucrative artefacts that continue to have cultural prominence in the digital age are in Ireland.

If the cultural case doesn’t get you, then listen to the economic argument. In Ireland, the Book of Kells in one normal year generated €12.7 million from those just looking at it and another €5.2 million from the giftshop. (4) The animated film The Secret of Kells generated over $1.8million, (5) there are numerous books, too much tacky merchandise to even begin listing not to mention that every artist even touching on Celtic design has at some point ripped off the Book of Kells, some relentlessly. Lecture theatres can be filled, courses run and careers spent all with this one object as their focus. It does not take a mathematical genius to realise that even if several million was spent acquiring, or a few thousand borrowing or reproducing something that had even a fraction of the pull of Kells, that there would still be a substantial return on the investment.

What can be done about it? There’s plenty of contenders when it comes to manuscripts held by institutions that may well be of Scottish origin but even the Book of Deer, unique in boasting 100% solid Scottish attribution is only on temporary loan from Oxford. No matter the provenance, even if the Book of Kells’ missing cover turns up in Portmahomack with a name and a date on it, Ireland aren’t likely to send the rest of it back. But we have the workshop, the original tools and the capacity to carry out the research to work out how these objects were actually made, so why not just make a new one?

This is the plan, I’ve been practicing for quite a few years and am now ready to have a go at it. Making the parchment and pigments, working out the design and recreating an illuminated folio from the Book of Kells just how it could have been done at Portmahomack. This project will run as a crowd funder through Kickstarter and has got some of the world’s leading manuscript experts on board to make sure it’s done to the highest possible standards. The pigments will even be analysed by Team Pigment at Durham University using the latest Raman microspectography to test for accuracy. If successful, the results will be exhibited at Tarbat Discovery Centre next year.

Notes

(1) https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-gaelic-language-plan-2016-2021/pages/4/0

(2) https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp10esil/p10esil/ilg/

(3) https://www.gla.ac.uk/news/archiveofnews/2018/april/headline_580550_en.html

(4) https://www.irishexaminer.com/business/companies/arid-40268015.html#:~:text=A%20spokesperson%20for%20TCD%20said,million%20revenues%20generated%20in%202019

(5) https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0485601/

THE LION LOOKS FAR EASTERN ??

It’s from the Book of Durrow around 650AD, so fairly solid Irish provenance, the colour scheme however is reminiscent of Ethiopian manuscripts and the North African desert fathers would have been a big inspiration for the Irish. Papyrus was found in the lining of the Faddan More Psalter which was buried since at least the 9th century, so its highly likely that Coptic art was circulating, but far eastern is unlikely.

Isn’t the term ‘Scotland’ bit anachronistic in relation to northern Britain in the early Middle Ages? Surely the Scots then were still ‘Irish’, which would make any modern dispute about the provenance of the Book of Kells and similar artefact ‘Scottish’ an idle one. Surely the theory that the production of Book of Kells was started by the community of Colmcille in a monastery in what is now Portmahomack on the Tarbat Peninsula and continued at some later date by the same community in a monastery in what is now Kells in the Boyne valley hardly makes the artefact more ‘Scottish’ than ‘Irish’.

The important role that communities like Colmcille’s had in transmitting the ancient wisdom and literacy of the Greek and Roman worlds to medieval Europe isn’t to be underestimated, however.

Yes, the Scotland and Ireland division is nonsense for the period, but the point I was trying to make is that the manuscripts and other artefacts are falsely divided along these modern borders leaving Scotland with the appearance of a much depleted manuscript history. The same could be said for Northern Ireland particularly regarding treasures such as the Broighter hoard, found in the north in 1896, unionist leaders argued for it to be kept in Dublin instead of at the British Museum, then upon partition it ended up in a different country from its place of origin thud loosing the role it should have had in school history lessons (that may have improved now but nobody told me about it!)

From a parchment making perspective is questionable whether any of the Book of Kells was made in Ireland. The parchment in Kells shows evidence of bacterial breakdown as part of the production method, pin prick holes and burnished appearance. This is unlikely to be the method favoured in a limestone rich area, whereas Portmahomack using the much more labour intensive seaweed potash would be likely to use such a technique to increase efficiency.

My point is that, from a cultural point of view, the geography doesn’t matter. The artefacts of which you speak are neither ‘Scottish’ nor ‘Irish’ because they were produced by a community to which such later political distinctions don’t apply.

To put this another way, irrespective of where they were made, those artefacts are part of the cultural heritage of what later became the imagined community of ‘Scotland’ and equally part of the cultural heritage of what later became the imagined community ‘Ireland’, not to mention part of the cultural heritage of what still later became the imagined community of the UK of Britain and Ireland.

This is why we should eschew all questions of ‘national ownership’ when it comes to such artefacts and they should held in ‘museums without walls’; the very idea of their national ownership is absurd.

Fascinating, a great read, good luck with the project.

thankyou Jim

Could we not exchange one of th stones of destiny for the Book of Kells?

Cool

The carved stone is Pictish, referred to as a Class I Pictish Symbol stone. It is the image of a dog that represents the constellation of Canis Minor and in particular its brightest star Procyon which was a marker for one of the important festival days in the Pictish calendar. Controversially new dating evidence indicates that these stones were carved around 1200BC coinciding with the eruption of Mount Hekla in Iceland….an extended series of eruptions that continued for over two decades according to bog oak analysis and caused the Picts to carve hundreds of stones with the images of their stellar deities (that we recognise as constellations) as votive offerings to clear the dust laden skies and stop what had become an eternal winter.

There is another example of an Irish treasure that is likely to have originated in Scotland and that is the beautiful Tara brooch in Dublin that shares many features with the Hunterston brooch on display in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. The interesting thing with these so-called brooches is that they are not brooches but calendrical devices using the position of the Sun on the horizon to determine festival days during the year by aligning the long pin in discreet channels formed by amber beads decorating the surface of the “sun-dial/brooch” with the Sun. The evidence for its origin in Scotland comes from the angle marked on the brooch that describes the extreme positions of the Sun on the horizon at the summer solstice and winter solstice which are latitude -dependent and coincide with Southern Scotland and are too great to have been useful accurately at a more southern latitude such as Dublin