The Last Picture Show – How Scotland’s Film Culture Just Got Hammered

Flashback

Some time in the mid to late 1980s, I attended a short season of films by Shūji Terayama, a Japanese radical best known for his features, Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets (1968), and Emperor Tomato Ketchup (1971). The screenings took place at Filmhouse in Edinburgh, which I visited on a semi regular basis to see the sort of subtitled arthouse films I’d previously only been able to watch on small screen BBC2 or Channel 4. Tickets were cheap, especially if you were on the dole, as I was, and spending afternoons watching Godard and Fassbinder, or more current works by Derek Jarman or Peter Greenaway, was a steal for 50p.

The Shūji Terayamaseason, however, was something else again, and seemed to relate more to performance or visual art as much as film. One short film, Laura (1974), had a group of women address the camera directly, with Terayama’s assistant, Henrikku Morisaki, walking from the audience and through the slatted screen to become part of the film, breaking through the frame to interact in the flesh with what was happening onscreen.

Another film, The Trial (1975) focused on characters banging nails into various surfaces. The film’s grand finale saw Morisaki go among the audience handing out hammers and nails, inviting us to join in with the action being beamed onto the wall before us, and hammer nails into it for real.

I’d never seen anything like it, but found this coup de théâtre liberating and exhilarating in a way that opened up the possibilities of what film/art/performance could be, however much Terayama’s provocations were of their time. These days, as commercial concerns take precedence, such retrospectives are more likely to take place in a gallery space. Indeed, in 2012, Tate Modern in London hosted a Terayama season similar to that held at Filmhouse, and featured Morisaki taking part in Laura for the first time in twenty-seven years.

In Scotland, if a Terayama season was likely to be seen anywhere, enlightened curators might want to give it a slot at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, say. It would be ideal for the former Dean Gallery now known as Modern Two. Or it would have been until recently.

The Terayama season, and the climax of The Trial in particular, came to mind as I saw photographs of Filmhouse last week. The pictures showed the windows and doors of the venue where I’d been handed a hammer and nails to take part in Terayama’s film closed up with steel shutters. This action was taken after the Centre for the Moving Image (CMI), the umbrella body in charge of Filmhouse, Edinburgh International Film Festival and the Belmont cinema, Aberdeen, went into abrupt liquidation at the beginning of October. The building is already up for sale, and is described in the brochure from selling agents Savills as a ‘unique leisure-development opportunity.’ The property vultures are already circling.

The nails – or whatever is required to secure the steel shutters – have made the now former Filmhouse look like it is awaiting demolition as part of some slum clearance programme. This wasn’t done for any kind of artistic liberation as with Terayama’s film. This was about closure in every way.

Popcorn Double Feature

When the CMI issued its statement on October 6th2022 that it was to cease trading with immediate effect, it was undoubtedly as shocking to the more than a hundred members of staff who had just been made unemployed without notice as it was to the wider film community, both in Scotland and beyond. Here, after all, were several institutions that were long-standing high-profile bedrocks of cultural life, shut down overnight, with their fate in the hands of receivers.

The statement spoke of the ‘perfect storm of sharply rising costs, in particular energy costs, alongside reduced trade due to the ongoing impacts of the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis.’

The statement also cited payroll costs, inflation, trading at fifty per cent of pre pandemic levels, the rise of streaming services and public funding having remained at standstill over the previous eight years. It didn’t mention Brexit, but then, it didn’t mention the redundancies either.

Taken at face value, all of what it did say was as undoubtedly as true for CMI as it was for other institutions going bust, artistic or otherwise. Within hours of the statement being issued, however, noises off elsewhere suggested there was a lot more going on beyond it.

There was talk of managerial hubris, of out of touch top-down thinking that couldn’t accommodate new ways of seeing and doing things. When the figures were released of how much public funding CMI had received – £1.5m for the current financial year, an additional £250,000 additional funding for EIFF’s 75thanniversary year, £1.3m emergency funding to help recovery from the impact of the pandemic – eyebrows were raised. And when it became clear that CMI heads were aware of the organisation’s parlous state going back several years, those eyebrows raised even more.

Such eye watering sums are a long way from the founding of Edinburgh Film Guild, the volunteer run body set up in 1927, and who kick started the founding of EIFF twenty years later. EFG has been resident in Filmhouse since 1980, and has remained a separate institution to both Filmhouse and CMI. Now, however, EFG through no fault of its own has been made homeless, and has been forced to cancel its programme. This might have been lost in the outrage at more high profile organisations being lost, but it is perhaps the grassroots origins of EFG that those trying to salvage something from the CMI wreckage might look to for guidance.

Within hours of CMI’s announcement, a petition had been set up by filmmaker Paul Sng and curator of independent film events organisation Cinetopia, Amanda Rogers, public meetings held and a campaign to try and save – not CMI – but the institutions that had been in its care – been formalised, with Sng and fellow filmmaker Mark Cousins at its helm. Significantly, support for the campaign has also come from EIFF’s director Kristy Matheson, and Filmhouse programmer Rod White.

For all this heroic activity, there remained an overriding sense that, if the Film Festival, Filmhouse, Film Guild and Belmont can go, nowhere was safe. This despite the stampede of events great and small that have seen theatres, concert halls and festivals return to full operations for the first time since the pandemic. This was done with a heady sense of optimism that might have convinced some of the paying public that the so-called new normal was just a case of business as usual. If only.

As if on cue, the National Galleries of Scotland announced that Modern Two, the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art’s second space, housed since 1999 in the former Dean Gallery was being forced to close for the winter. The pandemic and rises in energy bills were again cited, as was the seemingly all-consuming ‘perfect storm’. Other organisations, including the National Museum of Scotland, and Dance Base, have indicated they too are under pressure to survive.

As sad and tragic as events surrounding CMI and Modern Two remain, none of it should come as a surprise. Nor are such crises exclusive to Edinburgh or Scotland. Of course, the enforced closure of venues due to the pandemic left its mark, as will the spectacular rise in energy bills. And Brexit. Let’s not forget Brexit, however it might be unboxed.

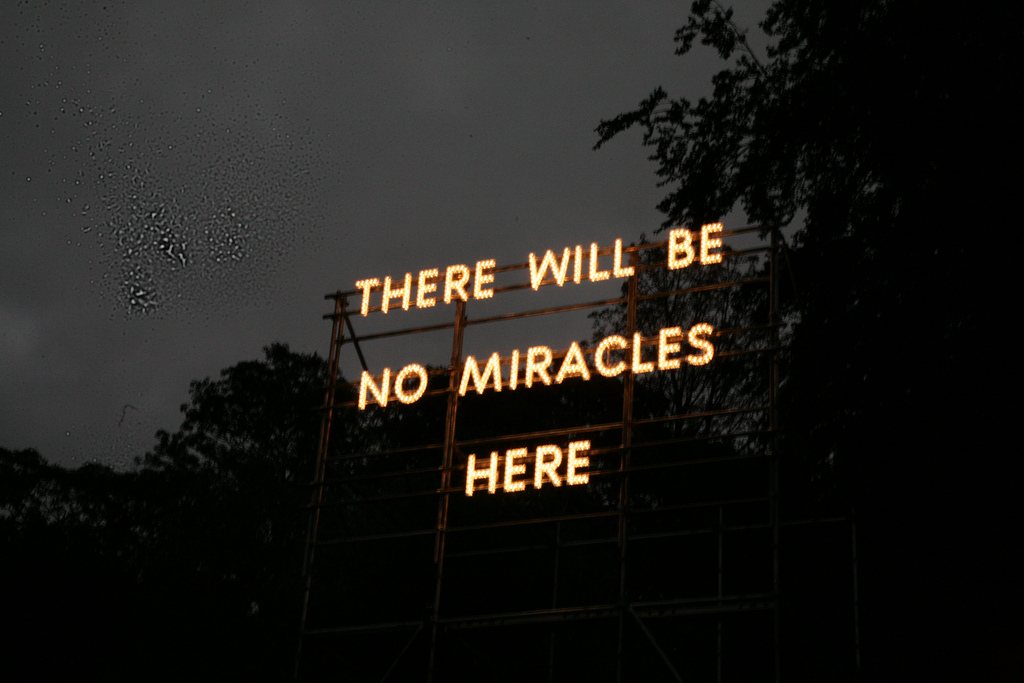

What has happened with CMI and Modern Two was an accident waiting to happen and is one likely to have more casualties. For all the well-meaning support that came from emergency funding packages, they were little more than sticking plasters shoring up what in CMI’s case, at least, looked like an already gaping wound. No one was ever going to be saved. As someone pointed out elsewhere, the words of Nathan Coley’s installation in the grounds of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art say it all. ‘There Will Be No Miracles Here’.

Re-Make/Re-Model?

An ancient Japanese proverb decrees that ‘The nail that sticks out shall be hammered down.’ Whether this had any kind of influence on ShūjiTerayama and his nail based film, The Trial, I have no idea. Either way, the proverb is said to mean something roughly along the lines that those jealous of those who stand out will do all in their power to hammer them into line with everyone else. Applied to the CMI collapse, it might be perceived as pointing to a form of top down thinking that, rather than liberating those with a hammer as Terayama did, becomes a form of maintaining control by whatever means are deemed necessary.

Meanwhile, beyond the CMI collapse, life and art go on elsewhere. The Edinburgh leg of the French Film Festival is about to begin screenings throughout November and December at both The Dominion in Morningside, and in multiple form artspace, Summerhall, which also has its own Summerhall Cinema! programme. Cinetopia, the curatorial film-based organisation led by Amanda Rogers, recently screened I Ken Whaur Im Gaun, an immersive film and sound installation exploring oral folk traditions in Scotland, at the French Institute in Edinburgh.

Cinetopia has also worked with Edinburgh based feminist-surrealist magazine, Debutante, on Electric Muses, a night of rarely seen women-led surrealist films at Leith Theatre. Then there is the likes of Braw Cinema Club, showing cult classics in the bowels of the Banshee Labyrinth pub, while Out of the Blue has hosted the social based Take One Action Film Festival.

These initiatives and other community-based cinemas past and present show the same sort of pioneering grassroots spirit that fired the founding of Edinburgh Film Guild by a group of cinema obsessives who wanted to see films no-one else was putting on. None of them need or needed a monolithic organisation such as CMI to helm things. But then, neither did EIFF, Filmhouse or the Belmont.

As it is, the collapse of an organisation nobody asked for has caused the need for a CMI Welfare Fund GoFundMe page to be set up. Give generously. Those made redundant deserve every penny.

Word on the street is that the EIFF name has been bought from CMI, and that the festival will happen in some form in 2023 after being offered space in Edinburgh International Festival HQ at The Hub. There is talk too of a potential film-friendly buyer for Filmhouse, while campaigners are also looking at continuing operations in other premises.

Beyond the current debacle, if one wanted to play devil’s advocate, one might suggest that the slow-burning disaster movie currently being played out in all sectors could actually take things back to some kind of level playing field again, where organisations were run from the ground up rather than the top down as is currently the case. Whatever happens next, that really might be something worth hammering home.

The CMI Welfare Fund GoFundMe page can be found here.

I’m all for communities like the CMI being governed from the bottom up, by their respective memberships, and their operations run from the top down by their respective management teams.. That sort of regime’s called ‘democratic centralism’, and it works well.

Happily, democratic centralism usually asserts itself when some existential crisis strikes a community and its membership mobilises its own independent response. According to its constitution, membership of the CMI community was restricted by its directors and subject to their approval and appointment, which restriction reduced the community’s resilience to such crises as it’s experienced.

I wish the CMI community and its members well in recovering from the disaster that’s befallen it. Perhaps that recovery will require the reconstitution of the CMI along more inclusively democratic lines.

Is this kind of top-down public funding of arts simply another form of corrupting patronage?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patronage

I was pondering the difference between professional ethics of historians and artists when considering that at least one Scottish historian, Tom Devine, has apologised for the failures of Scottish historians in general, in failing to report Scotland’s historical involvement in racialised chattel slavery (something that Edinburgh Council has recently apologised for too). Where are the Scottish artists who will stand up and apologise for the deficiencies of their art in tackling important issues, or in biases, or misrepresentations? If there are objective standards for good and bad history, what standards apply to good and bad art? And if there is objectively good and bad art, surely we should be careful not to fund, support, promote bad art to the detriment of the good?

Practical work on collective intelligence has gone into recommendation engines, of the kinds that use mass personalised choice data to build associative models, and clustering for common property abstraction. There are likely similarities in the ways human artists (who often work far more algorithmically and mimetically than most artists probably care to admit) learn their craft. And there are very low, approaching zero, costs for the public purse in letting collective intelligence make key decisions rather than some privileged elite of overpaid gatekeepers. Presumably artists will benefit from less artificial forms of feedback, too? Or are there no ethics in art, only aesthetics?

‘If there are objective standards for good and bad history, what standards apply to good and bad art? And if there is objectively good and bad art, surely we should be careful not to fund, support, promote bad art to the detriment of the good?’

You’ll find what you’re looking for in Tolstoy’s aesthetic theory, which claims that art is good to the extent that it’s morally edifying.

The trouble with theories like Tolstoy’s is that they beg the question as to what is to count as ‘good’. Tolstoy’s account of ‘the good’ depends on the pietistic form of Christianity to which he converted in his later life. Whose account of the good would you have art serve?

Your suspicion that ‘top-down public funding of arts’ is a form of patronage is spot on. It’s also apposite insofar far as this ‘top-down public funding’ enables the state to reward and privilege ‘good’ art, as defined by whichever ideological interest controls the state. The gripe that many artists have with Creative Scotland, the executive non-departmental public body of the Scottish Government that distributes funding from the Scottish Government and The National Lottery, is that it does so in accordance with evaluative criteria as to what is ‘good’ (deserving) that are unjust. According to Creative Scotland, ‘good’ art is art that realises some national and/or international benefit to Scotland in terms the contribution it makes to an understanding of Scotland’s national culture or way of life or in terms of the contribution it makes to the national economy, Many of us disagree with the Scottish government that this ‘good’ is what art is for.

The more general trouble with the aesthetic theory that the Scottish government’s arts funding policy presupposes is the same as the trouble that Tolstoy’s or any other ‘instrumental’ theory runs into, which is: Whose account of the good would you have art serve when there’s no democratic agreement on the matter or any mind-independent (‘objective’) standard by which we can distinguish the good from the bad with regard to anything, let alone art?

Verbose whataboutery.

@Alec Lomax, my comment, you mean?

I don’t actually draw clear distinctions between artists and historians, and artists and anybody else (almost everyone living can create art, and does, and arguably many non-humans too). I am just looking for any evidence of a professional ethos amongst professional artists of the sort generally recognised (movie-makers, portrait painters etc). I also imagine Tom Devine’s apology-for-historians-including-himself was an extremely rare and remarkable admission of professional failings.

I did a search and found John Byrne’s “veiled apology”: https://www.scotsman.com/whats-on/arts-and-entertainment/john-byrne-reveals-apology-paisleys-slave-trade-past-new-work-2887786

but it seems to have been a belated recognition of hometown crimes that have been suppressed in the popular imagination, and Byrne seems to be offering an apology for the crimes but not for the artists who have suppressed their knowledge of them from their art (for some 60 years in Byrne’s case, apparently).

I also get that there are many reasons for governments to channel public funds to the arts, including economic, and in developing skills to professional level that may be needed in future, and in filling a culture void that would otherwise be filled by other producers of culture, corporate and/or funded openly or covertly by foreign powers, like the CIA did after WW2 in Europe. Today, a lot of artists can apply their talents to the computer game industry which may have been embryonic or less when they first trained. It may even be essential to future Gaelic or Scots languages to permeate the digital world.

But how successful has this managed approach been? A recent article was headed “Danny Boyle says the British may not be ‘great film-makers’”. Does that apply to Scotland, only moreso?

I also think the distinction we conventionally draw between artists and historians is a misleading one. The bottom line is that historians are artists who produce work through the medium of language, in much the same way that novelists do.

Just so.

Last time I went to the Belmont I was the only customer. The staff outnumbered the customer by three to one. It was obvious what was going to happen. You use it or you lose it.

My youngest was a regular at the Belmont. I’ve been gifting him his membership every Christmas for the past three years. WTF am I going to gift him this year? (I’m thinking a BFI Player subscription?)

An excellent piece. A quick look at the CMI info on the Scottish Charity Regulator leaves one wondering what is actually behind the decision to go into administration. The balances do not seem particularly bad. More importantly, l wonder what will be done with the proceeds of the sale of the Film House? I imagine, they ought to be channelled in accordance with the goals of the organisation — maintaining the film culture. Perhaps for EIFF 2023?

The directors of the CMI have been expressing concern over major risks to the company’s solvency in its annual reports over the past six years. Those concerns have now been realised as a result of a ‘perfect storm’ of rising energy bills, other inflation, the impact of the pandemic and cost-of-living crises on ticket sales, the CMI’s struggle to secure new films on release, and the lasting impacts of the pandemic on consumer behaviour.

Since 2016, the CMI board has also been expressing concerns about its reliance on public funding, the loss-making performance of the Edinburgh Film Festival, and the sustainability of the Edinburgh Filmhouse building. The board first identified the Filmhouse building as a major risk to the future of the company in its 2016 accounts due to its limited development potential and the resources needed to maintain and operate it.

Insolvency should really have come as no surprise. The CMI recorded losses of more than a quarter of a million pounds in the two years prior to the pandemic. The company subsequently received more than £5.3 million in additional public money, including £1.3m in Covid recovery funding and and extra £270,000 ‘resilience’ funding to the tune of to help it stage the EFF’s 75th-anniversary this year. This extra injection of ‘free money’ is what gives the CMI’s last published accounts such a misleadingly favourable bottom line. The road to insolvency continued to be signposted by the 2019 accounts, which reported an overall loss of £261,953. The following year saw another loss £300,000.

The CMI pinned its hopes for survival on what it unveiled in March 2020 as ‘a bold new vision’ for a multi-storey building in Festival Square. This new building would have doubled the number of screens and seats for regular cinema-goers, created dedicated education and learning spaces, and developed an iconic festival centre, all within a fully accessible and carbon-neutral building, which would have reduced running costs and potentially increased revenues. However, the proposal attracted opposition from the heritage sector, Edinburgh City Council refused the project planning permission, and, as a consequence, the CMI could not secure funding for it.

The last set of CMI accounts to be filed, for the financial year ending March 2021, described the company’s underlying financial position as ‘fragile’. They warned that the company would likely become insolvent if it couldn’t meet the considerable challenges it faced. It identified those challenges as recovering revenues to pre-pandemic levels, resolving the long-running issues over the compliance and sustainability of its premises, and reimagining the Edinburgh Film Festival in such a way as to ensure it remained competitive in the global events market.

By mid-September of this year, the CMI had alerted the Scottish government agencies, Screen Scotland and Creative Scotland, that the company had failed to meet those long-standing challenges to its future viability and that insolvency experts had been called in.

The writing has been on the wall for CMI, the Edinburgh Filmhouse, the Belmont in Aberdeen, and the EFF for many years now. But, as Otis sang, you don’t miss your water till your well runs dry. We’ve only got ourselves to blame.

I’m not sure if ‘we’ve got ourselves to blame’ – I think we have funders paying good money after bad without Q and a cultural economy that soaked up billions over decades without a fund for the city … that’s the scandal right there

Spot on, Mike! That anonymous apologia won’t cut it. In fact, it illuminates the problem.

My analysis was intended to illuminate the problem. Mike’s right: the Scottish government’s policy of commercialising our cultural lives as ‘creative industries’ and then wasting scarce public money in subsidising failing enterprises.

And yet we continue to support that government… Of course, we’re on;y got ourselves to blame. We’re not victims here.

No point in doubling the number of screens if you are already struggling to attract audiences.

No point in building a vanity project cinema where no-one wants it, next to door to a defunct Lothian Road multiplex and down the road from Cineworld

Yep, I think that was the general opinion of the heritage sector in its opposition to the project: it would have been a poor investment; the money would have been more effectively – and less wastefully – spent elsewhere in the sector.

No. What we deserve, and must demand, is far better, and more open and accountable stewardship of our cultural institutions. The Scottish Governent has made no attempt to reform Scotland’s archaic, opaque, frequently abused, and often corrupt, patronage and public appointment systems. They seem to suit our political leaders just fine.

The ‘stewardship of our cultural institutions’ is fairly open and accountable through the regulation of Companies House and the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator, which ensure that the decision-making of those institutions is available to public scrutiny. The problem is that the public doesn’t often avail itself of that openness and accountability to monitor the performance of that stewardship. As I’ve said before, when things go wrong, we’ve only got ourselves to blame. We need/democracy requires us to be much more vigilant than we currently are in relation to the conduct of our public affairs.

Like I say, the writing was on the wall in relation to the CMI for many years. That writing was in the public domain, but we chose to ignore it. Now, we’re looking around for some ‘big boy’ to blame.

That looks like a very convenient line for those keen to avoid taking responsibility for a glaring failure of stewardship. I don’t buy it for a moment.

Well, you’re wrong, Graeme. We (the public) should have been supervising and holding the trustees of the CMI to account for their performance in the stewardship of that aspect of our cultural lives we entrusted to them. That we failed in our vigilance is no one’s fault but our own. There’s little point in closing the stable doors now or in complaining that they’d been left open; the horse has bolted.

I’m right.

We’re both right. We, the public, should have been holding the CMI’s trustees to account for their ‘glaring failure of stewardship’ far sooner. We left it too late. The trustees failed in their stewardship; we failed in our democratic responsibilities. It’s a sorry tale all told. It hardly bodes well for our independence if we, the public, canna even govern a pictur-hoose, let alane a sovereign state. We’ve a long way to go.

Yesterday I was wrong. Now we are ‘both right’. Try to make up your mind. And please don’t include me in your disempowering narrative of collective societal guilt. Doctrines involving self-flagelation are deeply unattractive and unhealthy, whether of the Catholic or Reformed variety. Patrick Geddes must be birling in his grave.

‘Yesterday I was wrong. Now we are “both right”. Try to make up your mind.’

Don’t worry. My mind’s always changing in dialogue with others. That’s how my thinking evolves. I’d hate for it to become set in its ways.

I’m not telling a tale of collective guilt. I’m telling a tale of democratic responsibility and its failure in relation to the governance of the CMI, which has lessons we might usefully learn for the governance of Scotland, one of those lessons being that we should remain constantly vigilant with regard to the decision-making of those whom we entrust it.

And I agree: masochism (mind-sets that involve submission and self-flagellation) are deeply unattractive and unhealthy.

Anyway, your wrongness lay in your claim that what I said is a ‘very convenient line for those keen to avoid taking responsibility for a glaring failure of stewardship’. It isn’t.

Assuming collective guilt for a failure of vigilance does serve the interests of those who would seek to exculpate themselves from a failure of stewardship. As a society, we have a right to expect those who sit on the boards of our institutions to accept responsibility when things wrong. They cannot simply be allowed to shrug and say, “Ah well, you should have kept a closer eye on us to prevent us from wrecking the ship.”