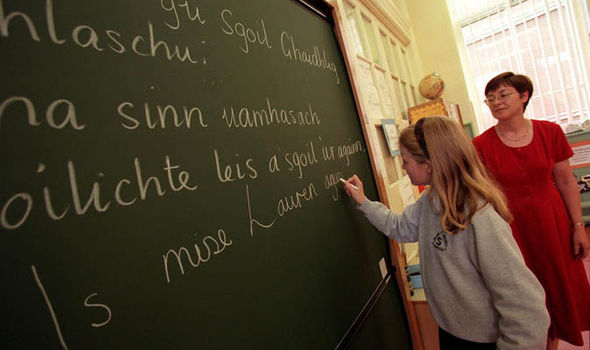

Expanding and strengthening Gaelic education in Scotland

Sixteen years after the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005 came into effect, Gaelic remains at the margins of the Scottish education system and the overwhelming majority of Scottish pupils leave school without ever studying the language in any way. The Scottish Government’s current consultation on Gaelic and Scots policy includes a proposal for a new strategic approach to Gaelic-medium education (GME). This review is not before time, as there are significant problems in the system, some of them going back decades, and progress has been limited and slow. Local authorities, the Scottish Government and teacher education institutions have all been insufficiently proactive, and it now seems clear that the current Gaelic Act is not robust enough to bring about significant change to the system.

It would be unfair to deny that there has been a measure of progress. The number of pupils in primary GME has risen by over 80% since the Gaelic Act came into effect in 2006, but remains only 1% of the national total. Improvement at secondary level has been slower: pupil numbers have only increased by 34% since 2012, only 0.5% of the total. Growth has been largely limited to larger urban locations, although there has been encouraging progress in the Western Isles in recent years due to more proactive (and long overdue) policies there.

The Gaelic Act requires all public bodies in Scotland, including local authorities, to develop Gaelic language plans if requested by Bòrd na Gàidhlig, the statutory language board. 30 of the 32 local authorities now have such plans, but remarkably 13 of these councils make no provision for Gaelic in any of their schools. Three other authorities have recently begun to offer GME (or committed to do so) but only following extensive grass-roots campaigning by parents and application of the Education (Scotland) Act 2016, which imposes some limited obligations on councils to offer GME.

A key problem with current arrangements is that too much is left to the weak, underfunded Bòrd and there is not enough leadership and direction from the Scottish Government itself. The situation compares very unfavourably with Wales, where the Welsh Government imposes clear numerical targets on each local authority in relation to Welsh-medium provision and requires all authorities to prepare a Welsh Education Strategic Plan.

A key element in the new strategic approach must be some kind of legally enforceable right to GME (a demand pressed, unsuccessfully, since the 1990s). GME provision in Scotland will soon enter its fifth decade and it is now clear that nothing other than the ‘stick’ of legal obligation will make authorities prioritise the matter sufficiently. But working out the details would be difficult. First, would it encompass pre-school (3-5? 0-5?) education as well as primary? To what extent could the right extend to the secondary stage? For primary GME, what restrictions might be appropriate in terms of pupil numbers? The counterpart right to French or English-medium education in Canada, for example, applies only where ‘the number of children of citizens who have such a right is sufficient to warrant the provision’. The 2016 Education Act uses a benchmark of five pupils in a year cohort, but in many rural schools the entire year cohort will be less than this.

The standard argument against a formal right to GME – rehearsed repeatedly since the 1990s, when campaigners began to press this demand – is that a shortage of teachers would make it undeliverable. This shortage has been a constant problem since the early 1990s and, despite important improvements in the last few years, recent research demonstrates that the number of new teachers entering GME is falling far short of the numbers required. Yet it is clear that the authorities have never really made Gaelic a serious priority. Strikingly, the Scottish Parliament’s Education and Skills Committee published a 73 page report on ‘Teacher Workforce Planning for Scotland’s Schools’ in 2017 that made only one reference to Gaelic, simply including it in a list of subject areas in a numerical table.

Learning from Wales

Again, the Welsh example is instructive. The Welsh Government has developed a comprehensive 10-year Welsh in Education Workforce Plan, which articulates with local authorities’ Welsh Education Strategic Plans and also requires teacher education providers to work towards 30% of their intake training to teach through the medium of Welsh.

Workforce planning for secondary GME is much more complex than for primary, however, as the current level of provision is so very low, and a full secondary curriculum requires teachers who not only have advanced Gaelic language skills but expertise in a wide range of specialist subjects, from maths to drama to graphic design. However, it is clear that current arrangements, with almost no systematic recruitment and development plan to bring new specialist teachers through the system, are not succeeding. As far back as 1994 the schools inspectorate criticised the fluctuating and incoherent nature of secondary GME ‘in a number of subjects, determined by the vagaries of resource availability’, yet the situation in 2022 is little changed.

An additional area of difficulty is the development of free-standing Gaelic schools as opposed to units within English schools. For the last fifteen years, policymakers have asserted the position that dedicated schools provide a better environment for Gaelic language acquisition than the unit model, but progress in the development of Gaelic schools has been painfully slow. Obstacles are both political and financial in nature; building new schools necessarily involves significant capital expenditure.

Gaelic in Edinburgh

The situation in Edinburgh probably shows the shortcomings of the current system most clearly. Following a long and difficult campaign by parents, the council opened a Gaelic primary school in Leith, Bun-sgoil Taobh na Pàirce, in 2014, but plans for a dedicated Gaelic secondary school have now reached an ‘impasse’, according to the local Gaelic parent group. Against the clear wishes of parents, the council pushed a plan for a secondary at the far end of the city (Liberton) that would be ‘co-located’ with an English-medium school. In March 2022, the council agreed to postpone a decision pending further consultation and investigation of potential alternative sites in more central locations. Since then, despite an explicit commitment in the 2021 SNP manifesto to a location in central Edinburgh, neither the Scottish Government nor the council has been unable to identify a suitable site. There are also significant questions about sources of funding.

The council has just opened an annexe to James Gillespie’s High School , the English-medium school where secondary GME is currently provided. This will create some additional capacity but it is no more than a stopgap solution. Unfortunately, the failure to develop a workable plan for secondary provision will almost certainly preclude the opening of additional primary schools in the city, even though the existing school reached capacity several years ago and overwhelmingly caters to the northeast of the city only.

Oban, Inverness and Glasgow

At the same time, parents in Oban have shown strong demand for a Gaelic school, replacing the long-established Gaelic unit, but Argyll & Bute Council has refused the proposal for financial reasons. In Inverness, proposals for a new 3-18 Gaelic school have not meaningfully advanced after a decade.

Compared to other authorities, Glasgow has made good progress with developing new primary schools; the city’s fourth Gaelic primary is expected to open in 2024. But even in Glasgow, insufficient capacity has meant that children are being denied places in primary 1 (17 of them in 2022-23).

Here too Canada may show a possible way forward. Parents who have the right to English or French-medium education also have ‘the right to have them receive that instruction in minority language educational facilities provided out of public funds’, again ‘where the number of those children so warrant’.

The focus on GME in the consultation is arguably too limited, as there are even more obvious problems in relation to provision for Gaelic learners, which has attracted less attention from policy-makers than Gaelic-medium education. This makes sense at one level, as GME clearly brings better outcomes in terms of language acquisition. But multiple pathways into Gaelic are needed, not least because a broader and deeper pool of future teachers is required. GME is offered in only 1% of schools, and has no access points beyond primary 1.

Only 32 secondary schools out of 356 in Scotland offer Gaelic for learners, almost all of them in the Highlands and Islands. The number of schools has not increased in a decade. Learners’ provision in primary schools has actually undergone a rapid decline in recent years, from 154 schools in 2017-18 down to only 75 in 2020-21 (out of a national total of 2,031). This is a massive failure of the much-vaunted ‘1+2’ language programme in Scottish schools.

Technology might provide a solution here, but the evidence so far is not encouraging. Pupils from all schools in Scotland are now enabled to enrol on National 5 and Higher classes via distance learning through the e-Sgoil programme, but in 2022-23 only 5 learners are enrolled on the National 5 course and only 3 learners on the Higher course. (The courses are much more successful in attracting adult learners, with 105 enrolled on the National 5 course and 43 on the Higher course).

Finally, in relation to adult learners, it is impressive that the Welsh Government has introduced free Welsh lessons for all adults aged 18-25 in Wales, as well as all teachers and teaching assistants. Too often, expense is a barrier to Gaelic learning opportunities in Scotland.

The current consultation is probably the most important initiative for Gaelic policy since the SNP came to power in 2007. There are numerous challenges and education provision is only one of them. It remains to be seen whether the Scottish Government will contemplate significant strengthening of current policy, including meaningful legislative reform, and if much-needed additional resource will be applied to ensure effective implementation.

“Welsh in Education Workforce Plan, which articulates with local authorities’ Welsh Education Strategic Plans and also requires teacher education providers to work towards 30% of their intake training to teach through the medium of Welsh.”

Such a proposal will cause apoplexy amongst the Labour supporting clique in the senior ranks of the EIS and SSTA! They will claim that pupils will start abusing teachers in Gaelic!

They opposed the introduction of Scottish literature and Scottish history.

Let me be clear: The EIS membership has a long and distinguished record in promoting innovation and pupil welfare in Scottish Education sine the mid-19thC, but, it tends to support the most voluble and nasty staffroom elements.

https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2022/05/22/scottish-nationalisms-trade-union-problem/

What precisely is the goal for Gaelic?

And how/where does Scots fit in?

the goal should be to regain the position as the national language, it can be taught bi lingually with scots. part of being a nation state is being able to speak your own language. there’s no need to play England or the unionists game by fostering the fake division of Doric against scots. what’s needed is planed infrastructure , linked with adult education, not the half arsed mishmash we have now, thought half arsed mishmash is what has defined the independence movement for the last few government’s. which in tern stems from cloudy minded unionism and civic nationalism, in a neo-liberal soup.

for a good example of a mullite lingual education system, look to Luxembourg as a model. to my mind the best situation for Gaelic is not to just have it in the hands of the local councils but a national program independent of that with provision based on population on one had and dedicated support for the west highlands and islands you can have both. We should better utilized the diaspora especially in eastern Canada then with the right institutions we might go a long way to bridging the gape in education providers to facilitate this. you also can’t separate Gaelic revival from housing and bureaucracy if the police health services legal and governmental etc. it has to be a 40 to 50 year plan I would say for the first faze to be serious and one that like the NHS and other institutions. can continue regardless of governmental changes. this is what a language policy should be, be that pro independence or unionist/federalist. there’s now point now talking about what should of been done in a sense, except to mark where we are now and look at the true landscape of the situation. I’ve encountered some pretty strong anti-Gaelic sentiment in the local SNP in the past, and a lot of what passes for scots is pretty half-arsed form what I’ve seen of late, but again a lot of the problem beyond these situations is the nature of neoliberal consumer culture.

From what I’ve read, Gaelic was the national language of most (never all) of present day Scotland for a relatively short time (peaking around the 10th century after the extinction of Pictish, and declining in the 11th or 12th with the arrival of Anglo-Norman gentry). Saying it should be THE national language undermines Scots, English, BSL and various other languages spoken in Scotland today.

What do you mean by “fostering the fake division of Doric against [Gaelic]”?

To the Editor of Bella Caledonia.

Hullo, there is little point in emailing me any more articles. Since you did not post my last two replies, it appears that you are not interested in any comments unless they fit in with someone else’s opinion(s). Yes, my posts are strong, but they are based on facts and not whishy, washy.

Every article printed is connected to our independence and lack of effort to achieve it by the Scottish Gov’t. I don’t expect you to post this article.

That should of been Doric against Gaelic.