The Wasteland

Listening to the radio the other day and they had assembled a whole panel to talk about Peter Kay’s return to standup comedy. If you missed it the four-strong panel agreed that Peter Kay was funny and fabulous and lovely and down to earth. Everyone agreed. We listened to his hit ‘Is This the Way to Amarillo?‘ and everyone agreed it was brilliant. The chat ranged for what seemed like hours. I went to the shops and came back and it was still on. It covered the fact that ‘we all needed a bit of comedy these days, didn’t we?’, although one of the panel admitted they hadn’t seen any live comedy for years. The conversation went on to cover how Victoria Wood was also funny and fabulous and lovely and own to earth, and that everyone missed her. Then something about Billy Connolly.

It was more like a cultural lobotomy than arts broadcasting.

The Gush

The problem in Scottish broadcasting and cultural commentary is just the gush: everything’s great, everybody’s lovely. As things close down it gets worse, and the world gets smaller and smaller. As the Filmhouse, the Edinburgh International Film Festival, the Belmont in Aberdeen and the Museum of Modern Art close, they are only the latest in a long line of shutting-down and institutional failure.

In Edinburgh the deterioration has been long and slow, live venues have closed and the capital seems colonised and asphyxiated by the annual jamboree: the Caley’s a Wetherspoons, Henry’s Cellar Bar closed earlier this year, the Odeon never re-opened, Calton Studios got shut down, many other venues struggle by.

Some of this about the cultural infrastructure of a critical media capable of moving beyond the hyper-banality of our print and broadcast output.

The Herald closed its Arts pages over a period of years – as one former writer put it: “without artform specialists, arts editor, arts news reporter, all that acquired knowledge of a dedicated arts team over at least twenty-odd years was lost overnight, and there is a ton of stuff going on great and small that gets no coverage”.

The List closed in 2020 and re-emerged after a crowd funder earlier this year, and the Scottish Review of Books was defunded in 2019.

But the List’s closure and re-emergence follows a pattern of failure, collapse and re-birth without often questioning what’s going on and what the core problem is. The List are now co-owned by Assembly (their offices are in Assembly Roxy). This is a major issue for a listings and review magazine and their editorial independence. None of the original staff have been re-employed. No-one seems to care about this.

To have a vibrant culture you need critical reviews standards and expectations, you need specialist arts journalists and to allow projects to build up a body of work over years.

Cuts to significant projects that have developed decades of work are ongoing. Joyce McMillan described the loss of the Arches in Glasgow as “cultural vandalism” in 2015. The groundbreaking NVA was shut down in 2018, and David Leddy’s Fire Exit theatre company was also turned down for RFO status in the same year.

These won’t be the last or the final announcements in the slow collapse. In 2021 the crisis in Glasgow arts (‘Funding crisis threatens Glasgow’s arts and cultural venues‘) was ascribed to the pandemic and mismanagement by the council. Having witnessed the School of Art being burnt-down twice, you can imagine confidence was not sky-high in the city. That year threatened closures included Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, the People’s Palace, Riverside Museum and the Mitchell Library.

But it’s not just about lack of funds.

There’s an almost total lack of strategy. Scottish creative arts and media seems to often lack any sense of connectivity between, say … writers, youth theatre, theatre, production, technology, actors, television, film. There seems to be often a lack of ambition and a drastic lack of confidence.

In 2021 the Lyceum came under fire for its casting when just two Scottish actors were announced in the Creative Scotland funded productions, a season of eight plays commissioned by the Royal Lyceum in Edinburgh and Pitlochry Festival Theatre. A statement issued by “a collective of Scottish-based actors and artists” described a casting announcement as “a complete dismissal and betrayal of the talent they have here.” The statement said: “This announcement would never be popular but in a pandemic as many of us sink and wonder if we can survive this pandemic it is a huge demoralising slap in the face.”

Elizabeth Newman and David Greig, the artistic directors of PFT and the Lyceum, respectively defended the decisions but Greig refused to accept that the actual casting of Angela (a new play by Mark Ravenhill) was an issue, saying: “It is good casting, I am really excited about it,” he said. “I do want to apologise that we didn’t present that well, particularly to our home audience.”

[after publication of this piece, David Greig wished to add clarification and context and we include this update for better representation of what happened]:

“In Soundstage we made 8 audio shows which employed 55 Scottish actors. we made 5 new Scottish plays. It was a 55% total Scottish creatives on that project which was UK wide in reach. The overall figure for the lyceum in 2021 is 80% Scottish actors.”

[if we make errors, we are happy to make public corrections and engage with the people we are discussing]

Surprise Surprise

There seems to be a disconnect despite the wealth of talented people we have across all of our arts and the opportunities they are given to work and create. Instead, we revel unquestionably in the Edinburgh Festival (s), pretend there’s an indigenous film industry, and stagger on until key institutions just collapse. Then we act all surprised.

Some of this is about leadership and some of it is about cultural confidence.

As Kirstin Innes has written in the P&J earlier this year discussing Alasdair Gray’s Settlers and Colonists essay and Nicola Benedetti’s appointment as director of the EIF:

“Every media outlet picking up on the story led with the information, flagged up in the second sentence of EIF’s press release, that Benedetti will be both the first Scottish director and the first female director in the festival’s 75 year history. But hardly any analysis of either of these facts followed.

An Edinburgh-based festival’s first Scottish director. In 75 years…”

“Are we ready for that conversation yet? Ten years on, soberly, respectfully and thoughtfully, maturely, can we ask what it is about Scotland that it takes almost 75 years for us to appoint a Scot to the biggest directorship on our arts scene? … It feels as though that figure, 75 years, has been marked just with a collective shrug. A: “Yeah. We know. Must do better.”

“We’re tired of the fighting; we’re scared to reopen that particular box. And, of course, there are so many other things that need our attention right now. But, at some point, a national conversation about the value of Scottish arts needs to happen.”

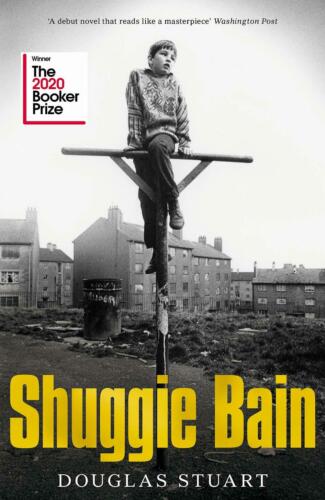

This reflection was prompted not just by the jaw-dropping banality of the Scottish radio show but the euphoria about the announcement of Douglas Stuart’s Booker Prize winning novel Shuggy Bain being adapted and coming to the iPlayer, and the other news Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things is coming soon directed by Yorgos Lanthimos and starring Emma Stone and Willem Defoe. While these are great it does somehow point to the poverty of the scene.

Where are the movies?

None of this is new.

Way back in 2011 Kevin Williamson wrote ‘An Open Letter to the actor, James McAvoy, concerning the Highland Clearances’ about the lack of Scottish cinema and television. He wrote:

“There is a wealth of stories from Scottish history crying out to get made into films but few of them ever do. It’s as if Wallace, Bruce, Mary Queen of Scots, Rob Roy and Bonnie Prince Charlie are the sum total of our history. Kings, queens and battles. Same as it ever was. Period dramas are the stock-in-trade of English cinema and television. There have been hundreds of them, some based on historical events, others on the classics of English literature. They flood onto our screens – and by our I mean Scotland’s – on a regular basis. I’m not complaining about this … But where are the corresponding period dramas from Scottish history? Where are the great movies set during the time of the Reformation, the Covenanters, the massacre of Glencoe, the Darien Expedition, the Act of Union, the hounding of the Jacobites [see Kidnapped poster – Ed], the Scottish Enlightenment, the trial of Thomas Muir, the massacre of Tranent, the Radical Uprising of 1820, the Highland Land League, the Industrial Revolution, the Victorian slums of Glasgow, or, as you say, the Highland Clearances?”

“The same applies to historical bio-pics. The lives of Robert Ferguson, Robert Burns, John Murdoch, Mary Ann Somerville, David Hume, Thomas Muir, Robert Louis Stevenson, RB Cunninghame Graham, or at the start of the twentieth century – Ethel Moorhead, John MacLean or John Logie Baird – were full of passion, high drama and incident. But where are the movies?”

Kidnapped : Cinema Quad Poster

Indeed, where are the movies, but also where are the plays and the tv? And how do they connect? The celebration of Shuggie Bain and Poor Things is great news, but it doesn’t really speak to an indigenous cultural movement as much as crumbs off the table. Equally the slump in Edinburgh’s cultural sector is jaw-dropping if you think of the millions of people that have come through the city with nothing to see for it. If there was no Oil Wealth Fund set aside from North Sea Oil, there is no Arts Wealth Fund that might have provided cultural richness and participation, not just to Edinburgh’s citizens but wider Scotland’s. That is a travesty of mismanagement.

This is not to say that there aren’t great things going on in Scotland right now. But the opportunity for greater ambition and connectivity seems to be constantly spurned and unfulfilled. It’s systemic failure and it has little or nothing to do with independence. ‘Soaring energy bills’ is the explanation for some of these crisis – and for sure the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis have taken a terrible toll on the arts and culture everywhere- but there’s a deeper malaise. Scotland’s cultural sector (sic) is listless, directionless and leaderless.

A lot to discuss as always but I have to begin by saying Catherine Wheels funding was reinstated -cutting your most successful producing company for children and young people in the Year of the Child with no underlying strategy about serving young audiences across the nation was an ‘odd’ decision, and quickly reversed. You thinking the company has been cut though perhaps underlies some of your points. Catherine Wheels, through natural development and in response to the environment it found itself in over the past few years is now thriving, a focus for artists and practitioners to work firstly in our base in East Lothian and then across Scotland. We, like many, are developing real relationships in our community, initiating and responding to their needs with works that cross the communities and generations. And on top of that we continue to tour, to schools, community and village halls, and venues with works for the whole family. In some ways we are doing well and in others like so many we struggle. But we have a story to tell, again like so many others of cultural work in our communities, bringing old and new stories and old and new voices to our wonderfully diverse audience. But if a tree falls in a forest and there’s no one to hear it? It’s telling that as we successfully finish another tour, packed audiences across Scotland, you were under the impression we were gone!

That said, the collapse of the established institutions gives artists themselves the opportunity to creatively ‘reset’ the relations of production within the matrix of which their practice takes place. These are revolutionary times for Scottish culture.

I am not equipped to judge the extent of cultural malaises in Scotland or elsewhere, but established, popular British mainstream science fiction seems to have taken a bit of a nosedive, with Doctor Who descending inexorably into fan fiction, and 2000 AD mounting some massive dismal crossover zombie apocalypse megastory. There were popular dystopian British science fiction novels from the 1950s onwards but the best of them had intelligent themes. Currently, the most-promoted seem banal and small-minded. I wonder if this is what fiction written by Margaret Thatcher’s children, grasping at Internet-memes for inspiration, looks like. No society, no analysis beyond likes stats.

But sure, intelligent and critical stuff will be found on the margins, maybe from foreign or amalgamated cultural sources, maybe homegrown (whatever happened to Royal Descent by Blackhearted Press? is that a bona fide case of censorship in the UK, like that graphic novel about the Business Plot was suppressed in the USA?).

And if you cannot manage a critical masterpiece to be quoted in the last Verso Book of Dissent, what about a character for our times, at least? Has Scotland ever produced a Lorax, a Poison Ivy or Swamp Thing? Maybe too much that gets promoted is created by city-dwellers these days, people who never had to make their own entertainment as children, because entertainment was piped to them everywhere in sterile encapsulated form, the establishment-approved model these days. All those filters at work, all that patronage, all the decaying striata of “Wha’s like us” poetry and prose, all those media dynasties. Where is the rage? Where the sap? The guillotine? Where is the future?

That’s the way to do it, Tony. My oldest son is a Panner and and my second oldest is a Belter, and they both cut their theatre-teeth on Catherine Wheels, mainly at the Brunton. The artist-audience link is crucial to ‘the arts’ and needs to be cultivated through the active involvement of production companies in the real communities in which they’re embedded (and vice versa). Catherine Wheels is a great example of how important it is to the health of ‘the arts’ that artists maintain this kind of embeddedness in their communities and don’t grow so high and distant that they become detached from them.

Donalda MacKinnon said she wanted to see BBC Scotland dramatising more Scottish literary classics – an ambition which remained unfulfilled on her retirement. Goodness knows where programme commissioner (note the unsubtle downgrading) Steve Carson stands on this. He appears to be completely invisible.

Steve was promoted from his role as Head of Multi-Platform Commissioning for BBC Scotland to that of the new Director of BBC Scotland following Donalda’s retirement from the post in 2020.

He said at the time of his appointment that his ambition is ‘to work with a talented BBC team and in partnership with the wider creative sector to support programme makers in making great content that reflects Scotland’s diversity and which can educate, inform, and entertain all our audiences’. In his mission statement, he didn’t prescribe what that content should be or from which of contemporary Scotland’s many cultural heritages that content should be drawn.

There is an overdependence on the beneficence of the central state in Scottish consciousness and culture. Alongside that, and interdependent with it, is what I have called for many years (see for examples my 1990 book Vulgar Eloquence) a recurrent swing in Scottish civic consciousness from omnipotence to impotence. The recent attempt to coerce into existence a grossly inappropriate multi-storey building in Festival Square which was to be a fantasy Film Palace of grandiose proportions, is yet another instance of this dynamic. The Filmhouse, its bar and eatery were doing very well. This daft piece of omnipotence has wrecked it.

‘The Filmhouse, its bar and eatery were doing very well.’

The problem was that they weren’t. The were being kept afloat only by ‘the beneficence of the central state’.

Spot on, Colin.

‘It’s systemic failure and it has little or nothing to do with independence. ‘

– a catalogue of loss, for sure. however, it’s not clear the author justifies the above assertion. especially as the lack of funds- either oil or arts- is recognised. ( a more accurate account would recognise that there are oil and gas funds- the former squandered by westminster, the latter spent in and on london.); and the unionist placemen- and women- are also recognised (gray’s essay).

so, howabout some proper analysis that does take account of these factors, and doesn’t come to the illogical conclusion that ‘it has nothing to do with independence’?

In what way could we not of accumulated funds for the city from the festival over the past 80 years? In what way could we not have developed a better connected more strategic arts sector? In what way could we not have developed a stronger indigenous film industry? We could have – and could now – do these things. In that sense it has nothing to do with independence.

Yep, ‘we’ is the operative term.

Artists are already well ‘connected-up’ through their creative networks (and this is producing a lot of exciting collaborative practice throughout Scotland). What they lack is a just political network.

But does the art-world need such governance? For what do artists qua artists need governance? Shouldn’t they just be left alone to make stuff?

Listen guys we are in serious danger of drifting into a world of online gobbledygook. I’m not being nasty or hostile. Just think about it.

By the way: is reCAPTCHA a robot?

An artist left on their own to make stuff will only work if the artist in question has money. Precious few artists I know have any. When an artist has no money, they will have to seek other employment and the ideas and culture they may have made – vital to a country knowing itself – will be lost.

Creating art is vital. But without funding, we are left with the imaginings of the wealthy and the elite. An entrenchment of their status quo as well, no doubt.

Creating art isn’t play, it isn’t easy and it isn’t something you can just do in the evening after you’ve finished the job you have to do in order to pay the rent and eat. Imagine a doctor only able to practice in the evenings because during the day they’re forced to flip burgers.

If you speak to any collection of artists, for example the Scottish Artists Union, they will talk about the necessity of Universal Basic Income. That’s an act that only government can facilitate.

It’s true that artists need to make a living like everyone else, and artists have supported themselves in various ways over the centuries, including the commodification and marketing of their own work. Happily, some of the best work artists have produced has been in response to their life-experiences outside of their practice as artists.

Art is play. Writing is playing with language, music is playing with sound, painting is playing with colour, shape, and perspective, photography is playing with light. It isn’t ‘work’ in the same sense that flipping burgers for wages or manufacturing a piece of pottery or a sound recording for sale is work; it’s the work we do to no end or purpose, for the sheer joy of doing the work itself.

A Universal Basic Income would provide artists, like everyone else, with income security. It would mean that they’d no longer starve should they become unable to provide for themselves for whatever reason. I think we should replace our current social security arrangements, which creates a class of ‘deserving poor’, with a non-discriminating UBI. But that’s another matter.

questions questions questions…..

‘accumulate funds from the city’: the city relies on income to fund other things: social work, housing, etc. are you saying arts are a priority over these?

‘develop a better connected more strategic arts sector’: as with radio fitba’, the ‘arts’ are reluctant to go beyond the glasgow metropolis. and are starved by the uk/london bias.

‘develp a stronger indigenous film industry’, as above. plus, have you not heard of cultural hegemony? as represented by the ‘leading lights’ of arts strategy in scotland (gray’s essay, which you yourself reference) n.b. ‘outlander’, filmed largely in scotland, but not shown on the bbc: gabaldion herself hinting at political interference.

also check out bbc ‘instructions to writers’, and of course heydrich on suppression of indigenous culture.

in that sense, it has everything to do with independence- or rather, the lack of it.

Up until the early 1980s there was Films of Scotland of course (which began in the late 50s). They produced hundreds of films. But this survived on industry sponsorship and they did not produce fiction but ‘documentaries’ that were thinly disguised advertising copy really. Nevertheless some of those films are genuinely good. Seawards the Great Ships (1960) won an Oscar and FoS supported lots of small film companies who made most of the films. What they did fell out of fashion badly but the endeavour and quality of some of it shows what could be done. Nothing really replaced it. Now its output is featured quite heavily at the NLS archive in Glasgow but as you say, where is today’s work and as important, where are the people like John Grierson, Murray Grigor and Eddie McConnell today?

You’ll find a lot of Scots publishing their work on platforms like Vevo and YouTube, though not always self-consciously as ‘Scots’.

Why are we so enamoured of the idea of having a national film industry? I can see how it could be used politically, to define and manufacture a national identity, but what value would such an institution add to the considerable film-making activity that’s going on in Scotland itself?

The problem with film is that it is expensive and logistically difficult to make at the quality expected to be ‘big’. It is the most industrial in that sense. So it needs lots of money that normally the filmmaker won’t have themselves. Where does that money come from? France has a pretty good film industry with I believe plenty of state sponsorship. It has a worldwide rep for its work. England can’t equal that but even there has some great and respected directors who made their way via the use of state money such that it exists in England/Britain (the BfI for example). For better or worse, films do tend to be labelled in reference to their country of origin. It isn’t particularly nationalistic, more about a character / style.

@Niemand, your example of the French industry, long rife with sexism (in a country which only gave women the vote in 1945) is actually illustrative of the problems with state patronage, when that state is patriarchal:

https://www.france24.com/en/culture/20220523-sexism-is-everywhere-–-so-are-we-feminist-riposte-hits-cannes-film-festival

I don’t know how many articles on Sexism and the French New Wave you can find online, but it’s a lot, and perhaps toxic stereotypes on screen have contributed to real social problems in society that have not gone away.

French films were parodied in in the UK in the 1990s with the Papa and Nicole adverts and its own parodies, and the template was not one many found comfortable repeating in British productions (although Peter Capaldi’s denial in taking on the role of Doctor Who seems to have been premature).

The film industry in France is less dependent on state subsidy than elsewhere other than in the US. This is due to its continued commercial success. According to a recent article I read in the Economist (I think it was), the film industry in France regularly recovers around 80–90% of its costs from revenues generated in the domestic market alone; more if you include exports. This is helped by the fact that French film-making generally eschews expensive settings, special effects, and other gratuitous gimmicks, which means it has much smaller production costs to cover.

Rather than simply throwing money at the industry, the French government supports the country’s domestic cinema in other, more sustainable ways that, at the same time, maintain its financial independence. For example: TV broadcast licences issued by the French government require the licensed companies to support independent film-making; special taxes are levied on ticket sales and the revenues they raise ring-fenced for investment in film production; private donations to film production are tax deductible; the sale of DVDs and streaming is prohibited for four months after cinema release to protect theatre revenues; both national and regional governments also involve themselves as collaborators in the co-production of films by multinational partners drawn from a wide range of cultural agencies (including, at times, the BBC and Channel 4).

One of the main reasons an independent film industry continues to thrive in France is precisely that it’s NOT a subsidy-junkie.

I should have made my point stronger, that even movies and documentaries containing mild criticisms or slightly negative portrayals can unfunded or banned in ‘liberal democracies’ like the USA (hence the number made in Sweden, I guess) or, to use the given example, France.

Three specific examples spring to mind, to the best of my knowledge: Paths of Glory (1957; made in the USA, banned for a while in France), The Battle of Algiers (1966; an Italian-Algerian co-production, banned for years in France), The Sorrow and the Pity (1969; a Resistance documentary commissioned by French government but banned in France for years, I think had to be finished in Germany). I guess many critically-acclaimed movies and documentaries were made against state opposition. Something similar happened to Peter Watkins’ The War Game in the UK.

Another more insidious influence comes when state agencies support or fund movies and documentaries but retain secretive script overview and order changes. This is the subject of National Security Cinema: The Shocking New Evidence of Government Control in Hollywood by Matthew Alford and Tom Secker. And such influence can be exerted beyond national boundaries, as when the CIA notoriously funded the British animated feature Animal Farm through a front, and got the ending changed to suit their preferences.

My understanding is that a tried-and-tested technique used by states who want to kill a project without seeming to be exerting censorship is to control the funding (which can look like it comes from private sources) and sabotage the production from within. Not so much strings attached but strangling vines. Of course, if you are not bothered about presenting a semblance of decorum and the illusion of free speech: codes, blacklists and witch-hunts (or Master of the Revels, paid informers and the Star Chamber of the Privy Council, for that matter). And lots of prison cells.

Yes problems of sexism is big SD but is that anything directly to do with funding as such?

Good points about the way the French government supports the film industry but not so much through direct subsidy. But it does do several crucial things that only a government can do. So it is still very much state supported.

My main reason for citing France is that they obviously have a major film industry and over the years they have put out some highly innovative, influential and quite brilliant work in a variety of genres. This should not be dismissed when we look at the state of the Scottish film industry or even the UK one. The UK government is reluctant to do anything that would help as it is generally non-interventionist on principle (let the market decide) whilst the Scottish government is often interventionist but in all the wrong ways that mostly seek control and then fail!

Something I always come back to is that a country only exists because of its culture. Without culture, a country is no more than a geographical area with some people in it, no different to the next geographical area. In that respect, it is vitally important. Witness the efforts of the British Empire in its eradication of local customs, languages, culture and more as it pillaged the globe. But in Scotland we’re doing it to ourselves these days, more or less.

The lack of collective interest in safeguarding our culture is palpable. Where a roll of government should be to facilitate that safeguarding – promote the necessity and importance of our culture – I see precious little interest or action. Crumbs off the table at best.

Much like the crumbs of our culture that escape us and find interest elsewhere. An adaptation of Poor Things is a brilliant idea, while the lack of Scots name attached to it is depressingly familiar. Imagine if we had an industry capable of reflecting ourselves back at us.

Even on the local level, cultural institutions seem broken, run by dead wood, or without funding or hope.

I know of a well-established arts organisation that will apparently not be allowing their artists to have open studio events this festive season, which is a vital period for artists to earn some money. The point of the organisation seems to have been lost somewhere down the line. I can imagine how this sort of situation is liable to be replicated across the country.

It’s grim and I see no light in the tunnel.

Um. What is the Saltire Society doing these days? It used to be active on many of the fronts discussed here.

It currently runs a meritorious awards programme that rewards excellence in literature, publishing, housing, and public art. It promotes the contributions of women to civic life through its Outstanding Women of Scotland community, and celebrates the contributions of individuals working in arts, humanities, sciences, and public life with its Fletcher of Saltoun Awards. It also supports the work of other cultuiral organisation through its bursary programme.

‘Culture’ is alive and well and as fit as a flea in contemporary Scotland. There’s a haill clamjamfry, an anarchy, of artists our there playfully making stuff. What it ‘lacks’, according to the politicos, is a functioning bureaucracy, which is not a bad thing at all. As I’ve said elsewhere, the bureaucratisation of art as ‘the arts’, the multiplication of administrators within its institution and the concentration of power in those administrators, extends a degree of bureaucratic regimentation into our practice and standardisation into our products. A functioning bureaucracy is inimical to art.

I disagree with the sort of nationalism that insists that ‘a country only exists because of its culture’. A country is just ‘a geographical area with some people in it, no different to the next geographical area’. The concept of ‘Kulturnation’, a people unified by the same culture, has had disastrous consequences in European history. In that respect, it’s vitally important to resist such expressions of cultural nationalism. The British Empire’s colonisation of non-European cultures in the name of ‘civilisation’ is a good example of Kulturnation.

The collapse of ‘the arts sector’, the Scottish ‘culture industry’, into anarchy is the light at the end of the tunnel.

“What it ‘lacks’, according to the politicos, is a functioning bureaucracy” – you’ve never heard of Creative Scotland?

But isn’t it the politicos’ complaint that bureaucracies like Creative Scotland are dysfunctional?

It is. It is.

Until culture commentators accept that the pandemic is ongoing, and lobby the Scottish government to address the death and serious illness it continues to trail in it’s wake, arts venues will continue to close because intelligent and informed people will not risk their future health for a night at the theatre. And as long as theatres and venues are willing to kill their audiences and their audiences relatives to satiate the raging egos of thespians and musicians, then good riddance to them. We have digital spaces where art and literature can thrive in the meantime.