The Question of Community and “Rewilding”

An invited response to Jeremy Leggett by Alastair McIntosh on re-wilding in Scotland.

An invited response to Jeremy Leggett by Alastair McIntosh on re-wilding in Scotland.

Last week the solar energy entrepreneur, Jeremy Leggett, published a blog titled Highlands Rewilding: governance and land colonialism on his Highlands Rewilding website. An accompanying tweet explained that it was an attempt “to address the thought that Highlands Rewilding might be just another form of land colonial[ism],” and it ended: “V interested in your thoughts @alastairmci et al.”.

I appreciate his courtesy, and recognise it as responding to my tweet reply of 22nd January that said: “Unless it has, say, a windfarm or asset strips/speculates, I’ve yet to hear of a Highland estate that returns 5% + dividends. But to me, the big question will be governance structures. ‘Rewilding’ must grant local communities power to the point of veto, or it’s land colonisation.”

In giving Jeremy my response here, and in having consulted some half dozen others who are well-informed both on the ground locally and around the wider “rewilding” debate in Scotland, this article is my reply to him. It tackles some of the background to the “rewilding” debate as it has come in to Scotland, my own locus for agency, legitimacy and invitation in engaging here, Jeremy’s business model and two of the affected communities (Bunloit and Tayvallich), insights from Eigg in the 1990s around community empowerment and veto; and the tensions between a capital-driven “rewilding” model and a politically-driven one that predicates community. Finally, I will bring it back to the question Jeremy raises, as to what would differentiate “rewilding” from being “just another form of land colonialism”. I have thus far placed “rewilding” in scare quotes. This is to acknowledge that it is a contested concept as it has recently evolved in Scotland. Henceforth here, and out of respect for Jeremy’s position, I will drop this practice except where I explicitly wish to highlight contestation.

Some Background to “Rewilding” in Scotland

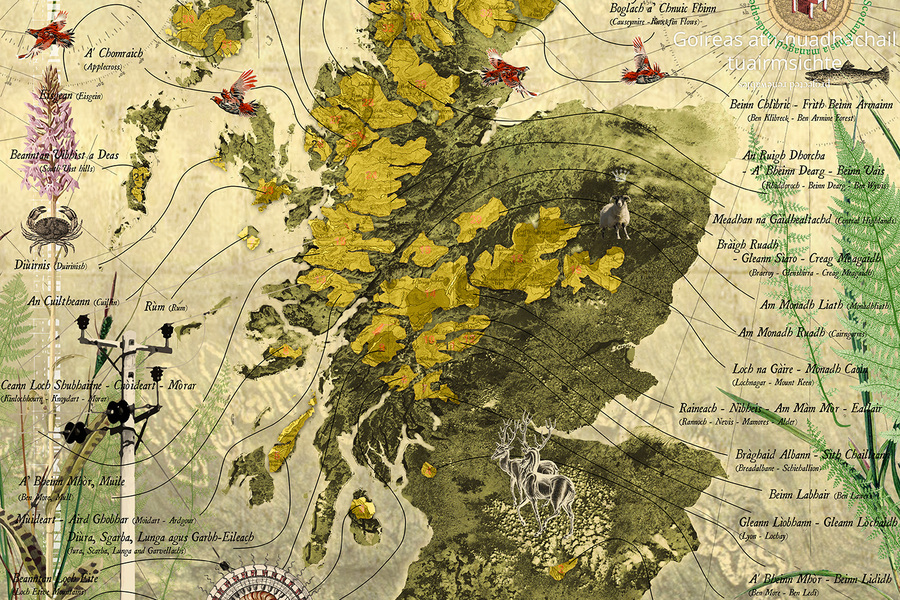

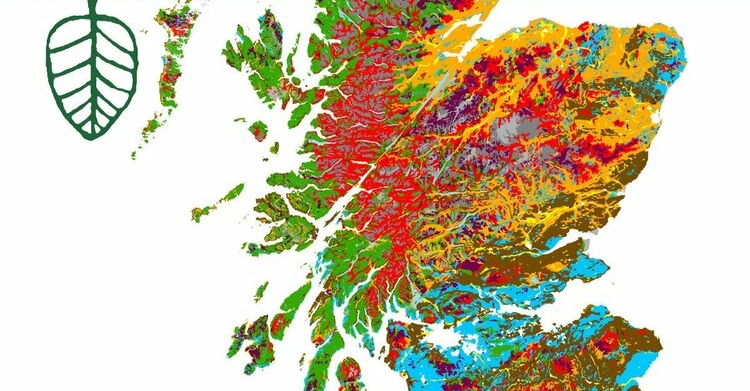

In May 2017, Edinburgh University’s Geography Department hosted the crofting historian, James Hunter, to deliver a public lecture called “Wild Land, Rewilding and Repeopling.” For Scotland, rewilding was the new kid on the block. South of the border, “rewilding” might readily invoke the MAMBA image of “miles and miles of bugger all”, a sheep-devastated bygone wilderness where hardly anybody lives. North of the border, we have our own perceptions on that take, and so the event drew in a full house. Many of us were wondering what to make of what felt like a parachuted-in term, perhaps the latest fad to freshly plough compacted ground. Hunter anchored its popularisation to George Monbiot’s 2013 book, Feral, which he called “a rewilding manifesto”. However, in cautiously treading around the concept, he warmed his audience by likening Monbiot’s vision to that of the Highlands-based ecologist, Frank Fraser Darling who, in the mid-20th century, had described Scotland’s depleted landscapes as “a wet desert”.

To Hunter, and most if not all of us present, there was no question about the imperative to rectify such ecological impoverishment. Organisations like Reforesting Scotland and Trees for Life have long been held in the highest public regard. However, it is largely because of sporting estate management practices, said Hunter, in his bluntest academic language, that “so much of our terrain, wild land included, is ecologically knackered.” As such, he broadly welcomed rewilding; but with a key caveat. To the people of a place, or those who were of a place prior to their forebears’ eviction in the Highland (and earlier Lowland) Clearances, land is more than just a “wild” blank slate. Put equally bluntly: “To them the place was home. Just that.” As Fraser MacDonald (one of the geographers who had helped Hamish Kallin to organise the lecture) later wrote in the London Review of Books, “Land can be owned; places are more complicated.” Consistent with such a confluence of natural ecology with its human ecology, Professor Hunter closed his lecture with in cautious affirmation. A big yes, for Scotland’s land to be, “put right ecologically. And socially and culturally as well.”

Landlordism as Rewilding’s Baggage

Over the past five years since that lecture, rewilding has pushed its way rapidly into public discourse. However, in Scotland the emphasis has been on how emergent narratives sit with Hunter’s final sentence. First, however, let me emphasise that the quite work of tree planting, and more importantly, caring for what has already been planted out or left naturally to regenerate, has continued at community grassroots. I have on my desk three issues of Reforesting Scotland magazine that I’d saved for future reference. Issue 55 from summer 2019 is a bumper edition “Land Revival” tour of community projects. Issue 64 from winter 2021 is on “A living from the land”. And the current Issue 66 of winter 2022, “Urban greening”.

Let me give an example. The Carrifran Wildwood of the Borders Forest Trust was set up by local residents in the 1990s, substantially driven by the vision of the Zoologist and human ecologist Philip Ashmole and his wife, Myrtle. Go walking there, as my wife and I did this past New Year, and you find a small but welcoming car park, thoughtfully constructed trails, discreet educational signage, and a most wonderful, house-high mixed forest that breathes new life and joy. Not only that, but the trees have been planted in a patchwork that has been sensitive to features of the cultural landscape, such as old walls and what appeared to be a high dry-stone-built stock enclosure.

We came away exhilarated. What was more, everybody that we had the chance to ask in the surrounding community spoke of the venture with the warmest and grateful enthusiasm. But the FAQs on its website are revealing. One asks: “Why don’t you often mention Rewilding?” To which, the reply: “We prefer to speak of ecological restoration, or reviving a natural ecosystem, because rewilding is a word carrying so much baggage, meaning different things to different people.”

What baggage? Fraser MacDonald, who has ancestral roots just a few miles away from Bunloit by the shores of Loch Ness, summed it up in a tweeted thread of July 2020: “So @JimHunter22 has already said this, but we need to talk about how landlordism is again being held up as an ideal for ecological restoration.”

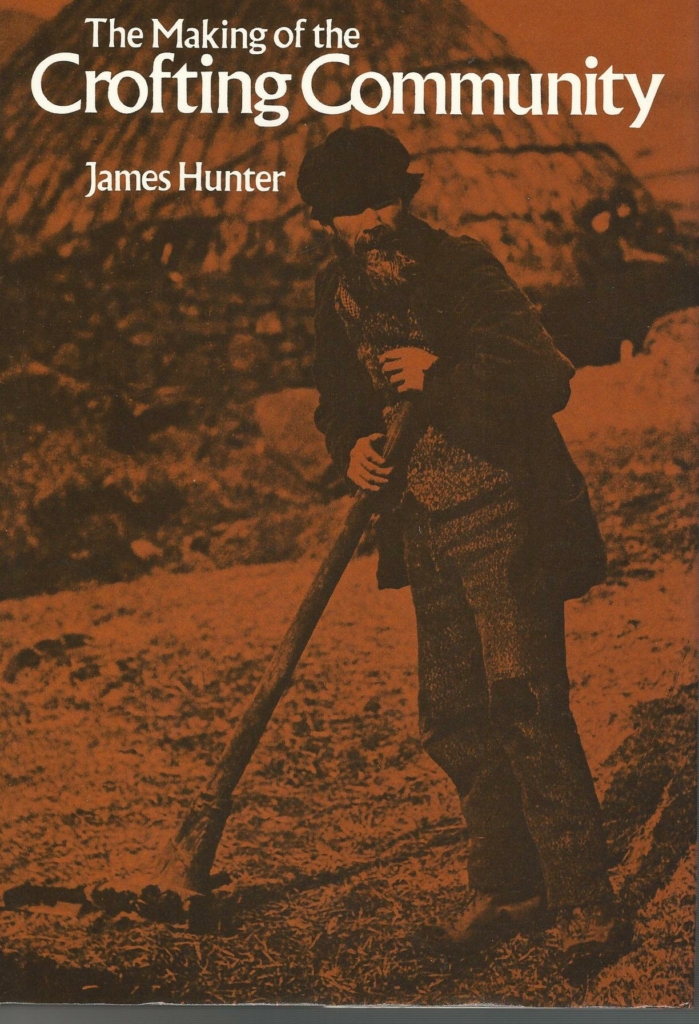

Many rewilders don’t realise the extent to which big private landlordism has been socially delegitimised in Scotland over the past thirty years. Whether it’s books like Hunter’s The Making of the Crofting Community or Andy Wightman’s The Poor Had No Lawyers¸ landlordism has been called out for what it usually is. Rentier extractivism and often, neglect. The hard-earned Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, twenty years old this year, has confirmed our historical right to roam and granted rights of pre-emptive purchase to communities, with additional enhanced rights for land under crofting tenure. More recent reforms saw the Scottish Parliament bring in a very active Scottish Land Commission, of which the 2019 report, Investigation into the Issues Associated with Large scale & Concentrated Landownership in Scotland included such findings as:

“Perhaps most worrying however, was the fear of repercussions from “going against the landowner” expressed by some people. This fear was rooted firmly in the concentration of power in some communities and the perceived ability of landowners to inflict consequences such as eviction or blacklisting for employment/contracts on residents should they so wish. Such fear is a clear impediment to innovation and sustainable development and has no place in a progressive and inclusive Scotland.”

In short, Scotland is not England. Our bioregions, our history, our laws and our cultural norms differ. It is in such contexts that Dr MacDonald’s remark would find broad affirmation from “the body of the kirk”. Such is the social context in which the debate around “rewilding” in Scotland is situated.

Dialogue with Jeremy Leggett

My involvement in land reform in Scotland, my legitimacy for agency, dates back especially to 1991 and when I was one of the four founders of the original Isle of Eigg Trust. This progressively transferred itself to the community, raising £1.6 million to bring the island into community landholding (a term that I prefer to landownership in such contexts), and reconstituting for this purpose in 1997 as the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust, being a partnership with Highland Council and the Scottish Wildlife Trust. In addition to writing Soil and Soul (2001) that documented the process, I have written two books on climate change, Hell and High Water (2008) and Riders on the Storm (2020), the latter with a concluding focus on the part that can be played community land trusts and the deepening of our shared humanity.

I say this to set some context for Jeremy’s engagement with me. But that context goes further. Bunloit in Inverness-shire, and Beldorney in Aberdeenshire, are the first two in ownership of perhaps an eventual twenty estates that Highlands Rewilding hopes to acquire. A third, Tayvallich in Argyll, is currently the subject of fundraising, with the seller having provided a window of opportunity that closes on 28th February.

A Twitter debate around this was picked up on by an old friend of mine, Ian Callaghan. Ian had worked with me and others in the 1990s on the campaign that stopped the proposed Isle of Harris super-quarry in a National Scenic Area. A former merchant banker who’d worked on the financial engineering of the Channel Tunnel, Ian now works with green investment. On seeing the Twitter exchange he dropped a line and asked if I’d be up for a Zoom discussion with Jeremy. This went ahead on 18th August 2020. Prior to it, Jeremy shared with me a working document that aimed towards “a final masterplan for execution of the mission.”

We spent what felt to me a slightly awkward hour in discussion. I could see that here was a visionary social entrepreneur. He had been the scientific director of Greenpeace International, campaigning on climate change in the 1990. Through his companies and charitable outreach, he had helped to make solar electricity affordable, profitable, and brought to bear on grassroots community needs in Africa. He was a whirl of can-do, must-do, energy; determined to give this part of his life to tackling climate change on a large scale and to do so, profitably, by drawing in financial institutions.

Why the awkwardness? It was just that: the masterplan. Here was a recipe for more concentrated land ownership. Here was a plan, top down, controlled by a hand-picked board of provenance mainly if not entirely from the privileged social echelons of British society. I had one set of questions that I kept pushing. “What is the local community’s view of this? Do you have their explicit consent? And what will be their latitude for agency if it proceeds?”

Within the bounds of “Chatham House Rule” confidentiality, suffice to say that Jeremy pitched to me the imperative of bringing private capital to the rescue of nature and climate change amelioration. I tried to urge him towards a deeper understanding of Scottish land history, politics, social class dynamics and the imperative of community empowerment as the basis from which to build a nation. I pressed him to seek out the local community council as a starting point in consultation, and that, as a stepping stone to meaningful participation. However, I was left with a sense that he had little knowledge or interest in the role of community councils. It was added humbug, for which he had little time that he could offer. We left our Zoom discussion there. We left it cordially, but perhaps a little coolly; or perhaps I misjudged, and it was just pensiveness on his behalf. Certainly, in what I read of his writings now, community is much more emphasised. But has it traction on the ground?

Highlands Rewilding’s Investment Model

Our next engagement was again on Twitter. On 2nd December last year, Tony Juniper, the chair of the government agency, Natural England, tweeted a Guardian article about “Citizen rewilders” being invited to buy shares in Highlands Rewilding. He asked: “Is citizen-funded & profitable Nature recovery about to take off? I certainly hope so. No-one better to lead the charge than @JeremyLeggett & @Highlandsrewild.”

In response to one of the tweets that followed I wrote, “But my question to Jeremy from the outset, has been: ‘Does this have the sanction & participation of the local community?’ … because, ‘Nothing about us without us is for us.’”

What followed became a highly fragmented owing to a frequent inadvertent use of quote tweets. He replied the next day: “Yes Alastair, full engagement … a long story, mostly positive but not all….” He ended it suggesting that the two of us might have another call. It was at this point I was contacted in a direct mail message by a Bunloit resident. They said that they didn’t want to start a Twitter spat, but there was a lot of local disquiet. I have since been given to understand, from more than just this source, that both the Glen Urquhart Community Council and the Glen Urquhart Community Rural Association have felt marginalised, and that when Jeremy talks of teaming up with “local community leaders” he mainly means “local business leaders”.

On seeing the suggestion that he and I have a call, an Alison Kidd @ecofunkytravel replied to the thread, saying: “It would be great to hear a recorded conversation between the two of you on this important & complex topic in the light of the shareholder issue.” This refers to Highlands Rewilding’s business model of selling £10 shares that it hopes will realise a 5% rate of return per year “annualised” (or spread out) over a ten-year investment window. Most of the investors are expected to be institutional. The invitation to invest offers local community members the chance to participate. This, however, will not be on a one-member-one vote basis as with a company limited by guarantee charitable structure. Rather, it will be on a normal limited company basis of one-share-one vote.

The Debate, and CLS’s “Rewilding” Criteria

Jeremy replied to Alison in a fresh quote tweet, 3rd December, saying, “Yes, that would be useful, I imagine and I would be happy to do so.” I replied the next day and suggested a Zoom with Ian Callaghan chairing. As a basis for the discussion, I shared a screenshot from Community Land Scotland’s “Position Paper on Rewilding, 2022”. It sets out three conditions to render “rewilding” acceptable:

- Firstly, we are strongly of the view that ‘rewilding’ initiatives should complement the policy objective of repeopling areas of rural Scotland rather than subverting it, and vice versa.

- Secondly, financial and related economic benefits arising from ‘rewilding’ initiatives should be retained by communities living within places generating such benefits, rather than being extracted from these communities, in accordance with the principles of community wealth building.

- Thirdly, communities’ voices should be to the fore in shaping the parameters of ‘rewilding’ initiatives within their localities, ideally facilitated through community ownership of land.

I must commend Jeremy’s openness in discussing this. He responded, 5th December: “Yes, happy to do that. Highland Re’s purpose is ‘nature recovery and community prosperity through rewilding’. So we won’t disagree on some of the CLS criteria. But prob. not the part of our model that shoots for external capital under mass ownership in accord with the purpose….”

In other words, to make this work with institutional investors, it has to be an extractive model, albeit hopefully hand-in-hand with a participative one. Moreover, explicitly hinging on the available of “natural capital” in Scotland, the model will rely on social capital built up by communities to add up. There are plenty of places in Scotland where ecological regeneration can take place just by putting up a deer fence (to simplify). The regeneration of Scots pines on seen from the road and train from Glasgow, just before Crianlarich, is a case in point. But for a model like Jeremy’s to work requires social infrastructure, and this is why the voices of communities becomes so important, and legitimate.

I replied that I’d consult with Ian Callaghan and ask if he’d chair a public debate, as he’d introduced us to each other in the first place. Ian agreed, albeit wary of the gender balance, but this was just how the history of the matter had brought us together, and what was needed to keep it as a dialogue rather than a panel event.

Enter, Tayvallich

We were about to set a date for after Christmas, when I received an email from a resident of Tayvallich, on the shores of Loch Sween in Argyll. This correspondent explained that their community had originally hoped to mount a community buyout. That would have been their best option. But with an asking price in the region of £10 million (the same as the Scottish Government’s entire annual Land Fund) it hadn’t got off the ground. They were faced with either the second-best option of Jeremy’s proposal (he seeming willing if he could find sufficient funding to go some way towards the community needs, mainly for affordable housing plots), or the worst option: namely that Highlands Rewilding might fall short of its target, and Tayvallich would be back on the market, with the estate’s tenanted houses likely to be sold as holiday homes, thereby eroding the community.

Jeremy was due to hold a public meeting on 9th January in Tayvallich Community Hall. I therefore held back on setting a date for the public Zoom. By all accounts, the public meeting went well. As Jeremy tweeted the next day: “An evening with the local community at Tayvallich mulling over what we would do together if Highlands Rewilding is lucky enough to raise the capital we need to purchase the estate by 28th Feb deadline. Well over 100 came. I left humbled and determined.”

In private conversation with some of the community gatekeepers from both Tayvallich and Bunloit, it was decided best to hold off the public Zoom while Tayvallich was at a sensitive stage. I was about to communicate so to Jeremy, when Highlands Rewilding (and I’d imagine, quite possibly, Jeremy himself!) tweeted, 22nd January: “What happened to the proposed online debate between your good self and Jeremy?”

I replied that, following consultation, it seemed best to hold back to avoid the risk of pushing the debate or its proponents into corners. I can be a feisty land reformer. There are times when that energy can be helpful, others when it is best held back! My reply comprised a 3-part tweet. It also explained a key happening that transformed the Eigg Trust over the period from its inception in 1991 to the community buyout in 1997.

Eigg, and its Community Veto Model

The original Isle of Eigg Trust of 1991 – so-called to differentiate it from the eventual Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust set up in 1997 to receive possession of the island – had been started by four of us who were resident on the mainland. In some respects, but without having access to financial institutions or the expectation of a return, we were like the board of Highlands Rewilding. We had not earned legitimacy. Why should the community on Eigg have trusted us? Why were residents not in the driving seat from the outset? What was the succession plan? All manner of valid questions were flying around. I discuss our painful wrestling with them in the chapter, “Too Rough to Go Slow”, of Soil and Soul. Above all, it was difficult because we were divided amongst ourselves. Once held, it can be difficult for Frodo to drop the Ring back down the Cracks of Doom.

Very quickly, our position in my view became untenable. The island was not yet in a position to lead the challenge to landed power. Yet at the same time, they were fast becoming sufficiently frustrated with how they’d been treated for too long that the need to take control of their own destiny was becoming more and more apparent. What we came up with, was a middle way. We would continue to run the trust and bring the island under community tenure. But we’d do so, by surrendering control of what we did to Residents’ Association. On the honour of our reputations, we’d offer them the power of veto over our decisions. That way, we’d work in partnership and alleviate fears, but with it being us, and not vulnerable tenants, in the firing line of landed wrath.

The Residents’ Association put this to a secret ballot in November 1991. It retuned a 73% vote of confidence on a 100% turnout. This granted us consent, if not yet quite the full blessing. That part followed in 1994, when in another momentous decision the islanders took over the full running of the “trust in waiting”, and held an election that appointed their own board. The rest is history. Indeed, that history can be heard unpacked in a podcast, “The Power of the Eigg Story”, that was released last November, convened by the island’s historian Camille Dressler and taking place between Lesley Riddoch, Andy Wightman and me, with the former Western Isles Labour MP, Calum MacDonald, in the chair.

Given this, then, as a “pattern and example” – a way of doing something and a case study of it being done – the question that I popped by Twitter to Jeremy and Highlands Rewilding, 22nd January, was whether they would consider a similar approach? With the communities into whose heritage they were buying and on whose social infrastructure they would in part be relying, would they also seek explicit consent, even blessing? I put it to Jeremy that this could this “a win-win, both for ecological restoration *and* community empowerment”, adding that it was “a question of how power is held, of governance.” It was why I had said earlier the same day – “‘Rewilding’ must grant local communities power to the point of veto, or it’s land colonisation” – this being the tweet that appears to have sparked, or at least informed, Jeremy’s governance blog with its opening volley:

“So if you are a Highlands resident much motivated by the iniquitous inequalities built up over 400 years in this region, it is easy to understand why you might listen to that and say: OK, fine, become a charity dedicated to both things, and let local communities run it. Or if not run it, then have an absolute veto over what it does. And if you don’t, you are nothing more than a new variant of the land colonialists that have long abused us.”

My answer to that is plain. If you presume to walk into any Scottish community without consent, seeking a steep rate of return as such ventures go and with a governance board devoid of locally elected representatives, then yes: you are just the latest “green laird” variant of land colonisers. “Rewilding” must grant local communities power to the point of veto, or its land colonisation. It may be that climate change justifies that, but if so, let it be by democratic mandate and not corporate shareholding.

But it doesn’t have to be as sharp-edged that. If the underlying driver is carbon capture through ecological restoration, look at what is being achieved in Eigg with both woodland management and its own world-leading renewable energy grid. Look at land trusts like the North Harris Estates with a major new woodland plan, that will employ as many as four local nurseries just in raising the saplings. Consider that the first of these has the Scottish Wildlife Trust as an integral working partner, and the second, the John Muir Trust. They work together, and it works because, as David Cameron of the North Harris Trust, Community Land Scotland and proprietor of the garage in Tarbert, Harris, puts it: there is “community desire”!

I would therefore put to Jeremy and his board the question: might not a binding pledge of community empowerment and control provide the means by which (as he put it last week in both his Scotsman interview and the video embedded in his blog) to release, “the full fighting force of the local community”? Might not such be a means by which rewilding and repeopling can walk hand in hand, with consent and even, blessing? Such words might seem quaint and even, “unrealistic”. But I put it that such as Eigg and Harris are showing what can happen when the inward gates of a community are able to open, and restore the flow of life back into the world.

Financial Institutional Expectations

The weakness of my testimony, as Jeremy will be quick to see and, probably, sorry to have to point out, has already been named in his blog. As he puts it: “Both financial institutions and local communities will require governance of the company in a form they can trust,” and that for the institutions, “trust will centre on world-class business experience among the board of directors.” But as his blog also acknowledges, investors like his ideas in the way that he has packaged them “because it would give them a degree of social license that they don’t have if they buy land in Scotland and try to manage it from afar.”

That’s progress, if it’s a social license to operate based on authentic local agency, but it also raises distinction between a capital-driven vision of land use and its impact on natural ecology, and a politically-driven driven vision that might more fully integrate the natural ecology with human ecology. Carbon credits or other business developments add up to what Jeremy calls a “land management reward system”, tipping the scales at 5% plus dividends. Such is straight out of the textbook of “natural capital” markets. Indeed, such is the expertise of the two directors whom he mentions based at SRUC, Scotland’s rural college. As the college’s web page for this aspect of its work explains: “Our goal is to research and build ecosystem markets to meet net-zero targets and reverse the biodiversity decline.” In other words, justified or otherwise, such is another form of land commodification. Indeed, as one scholarly paper just published and focussed on Scotland puts it: it is so on a “glocal” or global-local basis, whereby “questions around power and distribution of benefits arise as woodland expansion increasingly becomes part of green investment portfolios, environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) commitments…”.

My distinction between visions for the future that are capital-driven and politically-driven thereby comes into touch. This goes deeper than party politics. Rather, this concerns politics as the business of the polis, thereby of the body-politic, of the people; who in Scottish constitutional theory as well as by popular acclaim, “are sovereign”. Lest we forget, land reform was a driving force behind the creation of the restored Scottish Parliament in 1999. Land reform became its flagship legislation. The Land Commission exists because political options are on the table. For example, I would like to see land value taxation, exempt to community-accountable bodies, with the proceeds funding land buy-outs and the capital value of land being challenged in the process.

Such, however, is a personal view, and one not likely to come to pass before Tayvallich’s 28th February deadline. We must all be realists as well as idealists in this. What might that mean? And what, specifically, for a community such as Tayvallich? For here, the option seems to be either having some control with Highlands Rewilding, which has signified a responsiveness to the need for social housing and employment. Or alternatively, perhaps no control, if the institutional and other fundraising fails and the estate is thrown back onto the open market and to interests whose sole qualification to own land is, perhaps, their wealth? My locus for agency here is that I was approached by gatekeepers within both Bunloit and Tayvallich. With the latter, it is my clear impression that they would not want to damage the better for want of the best.

Openings of the Way?

In this essay I have suggested that an opening of the way might be a veto – perhaps exercised by each initiative’s local governing body that Highland Rewilding has in mind, provided that such bodies are at least in part democratically elected rather than appointed. Again, the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust has been an interesting model, with four of its board members locally elected, two appointed by Highland Council and two by the Scottish Wildlife Trust. An independent chairperson has the casting vote, though matters rarely if ever have to go to vote.

But there is another source of light in this tunnel. In a BBC radio interview last September, Jeremy said: “After my lifetime, the land is coming back to the people, there’ll be a trust dominated by Scots and Highlanders…” If by this he’s thinking in the longer term not just of £10 shareholders with Plutocratic voting rights, but of individuals, the residents of local communities regenerating alongside nature, then possibilities might open for staged models of ownership.

In the course of my taking soundings around earlier drafts of this essay, and asking if I’d missed anything, Ian Callaghan pitched in with the following, and with an email emphasising the “if”:

“My only suggested addition would be a question maybe at the end for the readership: If we agree that the sums involved are such that institutional investors are going to have to be involved, and that they can’t / won’t adopt co-operative style governance models, is there a new / third way of framing such governance? This would involve splitting the ownership of economic returns (for a defined period) from ownership of the land, which would be vested in a Trust or whatever. Once the defined return to investors had been achieved (including the repayment of capital), economic rights would also revert to the Trust. During the first period of joint Trust / investor ownership, the Trust would need to have rights to approve land management strategies and plans / budgets, based on an understanding of the need to deliver to the fullest extent possible the expected returns, but with a right to veto should the achievement of such returns only be possible by abandonment of the overarching objective of regeneration-with-people (which would need to be defined at the outset). Under this model, investors would sign up on the basis of accepting the overarching objective (which is in any case part of their own ‘return’) and at the same time would have the protection of knowing that, during the ‘returns period’ reasonable ways of achieving such returns couldn’t / wouldn’t be interfered with.”

Let me go no further than Ian suggested, leaving it as a question to readers; indeed, to affected communities in dialogue with Highlands Rewilding. My orientation is more towards political solutions to land reform, but we live in a pluralistic society and, once again, not squeezing out the better for holding out for the best.

Jeremy Leggett is under pressure to come up with the resources for Tayvallich in a month’s time. My sense, is that if lessons can be learned from Bunloit, and if he’s good to the impression that he left people with at the community meeting in Tayvallich, the wind might be behind him. The ball is in Jeremy’s and Highlands Rewilding’s court, but as they will see it, the ball will also be in the court of institutional investors who will be watching this debate unfold as they move towards their decisions. Another of my consultees, one from the Highlands and Islands but not one of the communities under discussion, concluded his email with an ecological metaphor:

“Leggett’s model is far from perfect. But he does seem to be honestly committed to what he is doing, and that commitment seems to be economically enabled, but ecologically, not economically, motivated. He’s loud, but then so is the corncrake though it is just a little bird. Other fish might be in the pond of green lairds and rewilding the Highlands, silent predators who know that making money can be done quietly. What might be their model and motivation? Do we risk forgetting about the worse?”

The bottom-line boils down to a community’s options, to the governance structures that might be agreed, to consent and ideally even, to invitation. Could it be that, were a mutually satisfactory governance structure to be agreed between Tayvallich and Highlands Rewilding early in February, a way forward might open out that would also satisfy financial backers? Might the community’s representatives then find themselves in a situation where they might assume control of their predicament by actively inviting Highland Rewilding? This, because their legitimate interests will, as reasonably as the situation can currently allow, have been secured?

Such is not for me to determine. But what I can say is that when the “inward gates” opened with Eigg during its six-year-long process towards community empowerment, at the end things moved with lightning speed. In community dynamics, as in nature itself, goodness and goodwill can release hidden powers. For as Hugh MacDiarmid put it in his poem, On a Raised Beach: “The inward gates of a bird are always open…. That is the secret of its song.”

Touching faith in Community Councils to safeguard agin this new colonialism. In my experience these councils are largely taken over by incomers who are as divorced from the ‘community’ as Legget, perhaps more so.

Spot on, MacGilleRuadh.

I have experience (2009-10) of a community cooperative bid for Forestry Commission land where housing was a major component. Out of 8 coop members, 6 were young locals, forced to move out of their native strath because of a housing shortage. All were qualified in forestry. We ticked all the boxes but lost out because acquisition rules dictated a “local community” meant postcode residents only. Most of them were retired “professionals” from the Central Belt or over the Border, incomers with no rural skills and none were qualified in forestry. They eventually became custodians of a large, glorified woodland walk.

Native seems to be a swearword these days. It’s a disgrace.

Thank you Alastair for a thought-provoking, measured and important contribution to this debate.

seems to me that there is too much tiptoeing round the issue of land ownership and the artificial construct of community buyouts. Some will work but the effort to raise funds and commitment is huge with a handsome publicly funded handout to private landowners.

it’s surely time to use land as the principal source of public funding. it would flush out the owners both private and public who would need to dispose of what they own if they couldn’t afford the AGR on it.

After a year or so it would become apparent what land the Scottish government might accept for rewilding if landowners offered to surrender it to government to avoid a substantial AGR payment.

I agree with most of the above comments, particularly those relating to ARG, which could have the effect of influencing landlord behaviour. However, given the apparent agreement in the article of the recognition that the depopulation of much of Scotland and the degradation of the land, has been due to landlords, largely from south of the border, treating our country either as there personal playground or a place to be exploited for thier enrichment. The most notorious example of the latter was probabably the Caithness Flow Country, probably the oringinal MAMBA Land.

Surely scotland is due some reapration for this, whether by those landlords or by the Westminster government, which has encouraged this practice as part of their Colonial Approach to Scotland.

I see parallels with many idigenous communities from those on an offshore island in Canada north of Vancouver Island, where communities are resisting logging operations and exploitatrion of the sea bed around their island, or the Amazon communities protesting against the whole sale devastation of their environment.

We in Scotland could lean a lot from them and the recent research being done by some groups in Scotland regarding the sovereignty of the Scottish people, along with the recognition that the land traditionally has belonged to the people not to a government which has failed to protect it, or has manifestly encouraged commercial exploitation by non-Scots to the detriment of local communities, The currebt situation where locals look out on wind farms yet are charged the highest electicity prices in the Uk is one of the more recent examples.

We should be asking Westminster for help with the necessary recovery of our land to fertility and re-population, since it was its actions now in and in the past which have caused many of our current problems.

We should be asking Westminster for help with the necessary recovery of our land to fertility and re-population, since it was its actions now in and in the past which have caused many of our current problems.

Good luck with that Ann!

Also we should not be so partisan as to blame all these landlord-derived woes on those from doon-sooth. Post Culloden clan chiefs were just as keen to ape their southern brethren. They still do: ‘Clan Cameron chief’s heir to lead Tory fight against any second Scottish independence referendum’ – Oban Times headline May 21.

Absolutely right Graeme. It is incredible to me how reluctant the SNP are to pursue this policy. In my view this would have been far more promising ground over which to contest the section 35 powers of Mr A. Jack. Instead of introducing AGR the SNP led government has wasted so much time and political capital on side issues, speaking frankly. I’m dumbfoonert!

For those who might be wondering AGR = Annual Ground Rent and is an alternative name for LVT = Land Value Taxation. See https://slrg.scot/ of the Scottish Land Revenue Group. I think the name was changed to get away from the idea of a “tax”, and to reframe it in terms of suggesting that landlords should pay rent to the community as a whole, just as they expect tenants to pay rent to them.

As for why this has not found greater political traction, the first thing to say is that the Scottish Land Commission (of the Scottish Goverment) issued a report in 2018 on LVT Options for Scotland and also a briefing paper. See https://www.landcommission.gov.scot/downloads/5dd6984da0491_Land-Value-Tax-Policy-Options-for-Scotland-Final-Report-23-7-18.pdf and https://www.landcommission.gov.scot/downloads/5dd69d3b1fba6_LAND-FOCUS_Land-Value-Tax-October-2018.pdf.

But the second thing to say, and a personal opinion, is that I think that radical Scottish politics are hamstrung at the moment because whatever party or parties hold the balance of power, they have to hold a broad chruch of middle ground. For the SNP (though possibly less so for the Scottish Greens) this means sidestepping policies that might frighten the horses. Frankly, I don’t think we’re going to see much potential for a radical Scotland to open up until the question of Indepence becomes more settled in the Scottish public’s mind. Too easily we put pressure on the politicans (of whatever party), forgetting that they can only lead so far ahead of the electorate without losing ground on one front or another, and therefore, losing power. Perhaps to the convenience of some interests, this generates cautiousness.

A related issue is the capacity for governance. A senior official of Glasgow City Council was saying the other day (privately) that they’ve taken early retirement because they were worn out “with having to conduct the managed decline of Glasgow”, and attributing this to the knock-on impacts of UK economic and “regional” policies. There’s just not the money around that there used to be in real terms, and Brexit and the loss of EU funding, an added whammy. As such, public servants generally lack the capacity to do what they’d yearn to do.

So cautiousness and capacity, to which there might be grounds for adding a third: complicity. For example, if an MSP has a second home or is socially close to landed power, does that influence policy? It’s dangerous to speculate without evidence, but on these three likely grounds – cautiousness, capacity, complicity, and dare we be honest and risk adding a fourth in some contexts, competence, I worry for where Scotland stands and personally, costly though it might initially be, I yearn for Independence so that, at least, our mistakes will be our own mistakes.

This is a well-constructed analysis of the potential reasons for governmental inertia, thanks. My gut feeling however (and there is no way to really back this up) is that the SNP’s cautious managerialism (even though the standards of management achieved are pretty abysmal) is possibly the greater risk for the cause of independence. A wheen of the folk in the middle ground will be looking for evidence of what a future Scotland might be like, what it might achieve and introducing such as AGR-probably in the teeth of Westminster and Landlord opposition -may (in my view) radicalise and inspire a proportion of these to finally ‘come over’. Granted it might push some the other way but I think the numbers would be smaller.

There is also the point that bold action is often required to break a deadlock situation. Isn’t it better to introduce something like AGR now if it is within even Scotland’s limited devolution powers because you think it is right for Scotland rather than let the topic be becalmed due to an undue deference or fear of a small part of the electorate. The utter incompetence, dullness and warped priorities of the current Scottish Government administration is surely not inspiring anyone in the undecided middle to adopt what would seem to them to be a radical option?

You could argue the whole country has become trapped in the current position. A highly cautious, risk averse Holyrood government nagging for indy through its own sea of mediocrity butting up agin a more muscular unionism that will increasingly favour red-wall England over a trapped, inert Scotland, mired in its own insubstantial powers? If a stalemate situation like that goes on for much longer I can see some abandoning the whole indy project altogether. Is it an accident that almost all renewable energy manufacturing jobs are on the Isle of Wight (that well known electricity generating area) or the NE of England?

I competely agree. I am not a well-informed follower of politics (and in this kind of discussion, there’s a danger of giving that impression, misleadingly). But I do pick up a gut sense of where the public mood lies, and as you suggest, I think that patience is wearing thin with a becalmed political scene that fails to kindle Scotland’s living fire.

In childhood trauma psychology, there’s a phrase sometimes used, “frozen awareness”. As I understand it, it’s a condition of seeing everything that’s going on in a hyperalert way, but being paralysed to respond. I’ve sensed that coming on increasingly in Scotland since the failure of the 2014 referendum. It’s visible right across the board, from land issues, to Brexit, even to the potholes in the roads. A mood of hunkering down and just accepting the degrading state of things, like the hard-pressed people in our neighbourhood (here in Govan), who are being screwed by benefits cuts or energy costs or food price rises or the bus service and ticket costs, and shrink into themselves. Even to the point of death. I mean, actually going to the funeral services, where poverty and its knock-on effects kills neighbours, or drives suicide attempts.

What can break through? What can renew the flow of life? AGR/LVT? A referendum? Strikes? A climate shock? A war? I lack answers that add up, except to suggest that what’s come on the UK as a whole and impacts Scotland in ways for which it has not voted, has been a long time building up. We’re seeing now the consequences of a hubris that culminated in the materialistic 1980s and 1990s with crass consumerism at the everday level and madcap wars of the new millennium at a UK national level, and now a dumbed-down populace where conspiracy theories so readily take root. Such over-reach in the outer life of the collective psyche has consequences for the inner life, both collectively and individually, as hubris meets its counterpoint in nemesis.

Again, that question: what then can renew the flow of life? I suspect it’s not going to come from the big outward gestures of political forces. Those levers are too spent. I think we have to rebuild ourselves from within, individually and collectively. We have to hold that awareness of what is going on and not flinch from it, but stand our ground in integrity, and ways that spread integrity. Then the roots can strengthen, individaully and through to the community writ large, the nation. That is why I see such as community land trusts as so important. I visit them, and see life coming back to life. It’s why this debate around rewilding and repeopling is important.

I don’t think the rôle of the Supreme Court can be overstated in the apparent reluctance of the Scottish Government to pursue wider land reform more vigorously. The individuals, families and syndicates who own so much land in Scotland are very well connected and not short of cash. The cult of individualism and the concept of “human rights” have achieved a perverse fusion in free market Blighty. Take on the estates and the SG could find itself ensnared in a multiplicity of financially crippling court cases; more fuel for the Unionist media screaming.

“It’s dangerous to speculate without evidence, but on these three likely grounds – cautiousness, capacity, complicity, and dare we be honest and risk adding a fourth in some contexts, competence,”

Spot on.

indeed Graeme, we seem to be mesmerized into a trance between the Victorian Edwardian Dystopia of land monopoly and a quasi-kibbutzist neo-tribal collective bipolarity. The issue of AGR collection is vital in wakening us up to wider options

‘Quasi-kibbutzist neo-tribal collective bipolarity’ – could be a good tshirt

Ron, hello … your comment (I think it may have been intended to Graeme Purves’ input, below) raises the question of AGR, which for those not in the know, is Annual Ground Rent, being an alternative to the older term, Land Value Taxation (LVT). I’d just like to give a heads up here to Andy Wightman’s blogs on land reform, including such fiscal measures. For example, his July 2022 reflection on the Scottish Government consultation paper “Land Reform in a Net Zero Nation”, here:

https://andywightman.scot/archives/4845

And also, his Land Reform Bill Consultation response, here:

https://andywightman.scot/archives/4884

I know you’ll be aware of all of that, Ron, but this is “pour encourager les autres”. Also, in posting such pieces I do not want to give the wrong impression that I have expertise in such fiscal and policy areas. I do not. My expertise, such as it is, lies in matters of land and community empowerment. Finally, Ron, every time I go up the A9 I look over to the left where you planted those experimental plots of trees ‘way back in the 1980s I think it was, and my goodness, what a testimony and legacy from an era when many said, “[deciduous] trees wouldn’t grow in the Highlands”. And look! There’s a picture of them strung out along the north shore, right here:

https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-a-view-of-loch-garry-from-the-a9-trunk-road-through-perth-kinross-97942445.html

Go well, man. A.

Interesting article. We need to be careful not to idolise the notion of “highland communities” I live in Glen Urquhart and on our little hill all the other houses are owned by retired English incomers, some of whom openly question the existance of climate change and would prefer a sporting grouse moor to any rewilding! The local council seem to struggle with simple things like glass recycling, so I welcome the vision, energy and enthusiasm Jeremy is putting into such an important issue. . Lets not shoot down those who try…

These Scottish lands are, or were, home to animals, plants, fungi etc too. Both top-down capitalist-friendly managerialism and community control are humanist and speciesist, and *both* are colonialist. I reject the options presented here.

I recently read Roger Lovegrove’s Silent Fields: The Long Decline of a Nation’s Wildlife, where the author dedicates a chapter to Scotland (England and Wales experienced the Tudor War on Nature, with parish bounties paid for locals to kill ‘vermin’, but apparently Scottish royals pre-empted them). Obviously not all animals killed in Scotland are killed by locals, and some locals are acting on orders from landowners. Yet local communities should face up to their own parts in making this modern country so nature-depleted. After running through a historical account, the author ends the chapter with:

“Since then, and regardless of increasing protective legislation, illegal persecution has continued to take a heavy toll on wildlife in Scotland. The upland areas of Scotland continue to this day [2007] to produce the worst annual catalogues of illegal killing of protected species anywhere in Britain.” (p78)

Locals like investors and planners may have their own superstitions, troubled histories, dark motives, exploitable weaknesses, and biases. Why should “goodness and goodwill” emerge victorious? Democracy is simply a means, but to what end? My recommendation is for a constitutionally-encoded biocracy which gives non-human life the decisive proxy voice in government. All the other options are humans acting like Lords Over Nature, and colonialism by other names.

#biocracynow

Thank you for the various comments, everyone, and can I just apologise for all my typos. I started off intending just a short reply to Jeremy’s invitation. But on consulting with others, the magnitude of what I was trying to tackle grew, and grew into the wee small hours. It exhausted me over the weekend, but because the Tayvallich deadline is so tight I prioritised getting it out quickly, albeit at the cost of insufficient proof reading. Hey Ho! But my thanks to Bella’s Mike Small for getting it posted promptly.

Alastair, this has been an excellent read, thank you.

I picked this up via the Bella Caledonia Mastodon account and it prompted many thoughts and memories about my own involvement with Eigg (as HC rep) and with the so-far unsuccessful attempt to take some form of community control in Lochaber over what is currently called the Jahama Estate.

I’m glad you highlighted the Eigg governance structure and how it offers a template to balance an outside interest with community control. The fact that structures like the Heritage Trust are therefore not considered compliant for Scottish Land Fund support is a great shame.

The requirement to be compliant and the financial scale of the “Jahama”/Rio Tinto estate in question led the East Lochaber & Laggan Community Trust to look at a version of the hybrid solution your refer to at the end of your article.

A twenty year, essentially fixed, funding period for an external financial interest is, in my view, effectively debt finance by another name, and that’s what we developed, with advice, for ELLCT.

I’ve no doubt that given the low return of 5% annually that Jeremy talks about, that his investors are actually debt-financing this – they may hold shares in the land-owning venture, but that investment is ultimately debt-financed. Otherwise 5% is not going to lift the skin off any investor’s porridge.

If the financial investors see the returns as reliable enough (and in accepting 5% they implicitly are saying exactly this) to debt-finance the purchase, then there’s fundamentally no reason why communities cannot do the same.

What they lack is the equity to provide the lender with a cushion. This is where the Land Fund could come in, should the Government be persuaded to allow leverage to be applied to the Fund’s grants…

Out of necessity, ELLCT tried to put forward a model for a wholly community-owned solution that provided a substantial financial return to outside investors who would finance the majority of the acquisition. I am out of necessity of space skirting many questions and issues of debt-backed community buyouts but fundamentally, I think that model is eminently possible – and the financial return offered by Highland Rewilding tells me it is possible. I suspect Jeremy would understand it is feasible, and maybe he could be persuaded to change, over time, to it.

@[email protected]

Thank you, Ben, that’s important on-the-ground experience, as are comments – not all of which support my position – from such as Roddie Maclennan and David Logie.

I keep reminding myself that, behind all this debate, is the huge historical injustice that land that was once in principle (if not necessarily in practice) held by clan chiefs on behalf of the clan (the family, or people of a community of place), with the chief in bardic poetry “the highest apple” on one tree, became deliberately corrupted by the policies of the Scottish and then the British state from around the start of the 17th century. I explore these in my book Soil and Soul, especially the chapters “By the Cold and Religious”, “Echoes Down the Glen of Landed Power” and “World Without a Friend”.

Large scale private land tenure is largely the knock-on effects of those policies. The same goes in England, buit upon the wholesale theft of the Commons during the Enclosures. In my view, the main difference between Scotland and England is that their experience was mostly further back in history. It became more lost from public memory, and arguably, even censored therefrom. (I find a TOTAL lack of English fine art of the Enclosures, compared with Scotland’s plenty on the Clearances via such artists as Nicol, Faed and McTaggart. A PhD waits to be done on that!).

Something I’m hearing in some of the comments here is the danger that focussing on such practicalities as financing for ecologial restoration or community buyouts is a displacement activity from the big picture. I agree, but only up to a point. I think that local, on-the-ground initiatives are hugely important. They build up change organically, taking communities with them and often doing so by peer-to-peer learning. And they provide “patterns and examples”. Patterns, as theories of change and ways of doing things. Examples, as case studies of what works.

I suggest that, but then, I am an evolutionary rather than a revolutionary.

This is a great article and the comments very interesting too. The thing I would like to pick up on is the conflict that emerges when ‘local agency’ is actually working against what I see as the absolute imperative to address the climate and biodiversity crises. I live in a lowland rural community with high value agriculture and I am an ‘incomer from the city’ – although I have been here 20+ years – who is trying to make a small difference in my own setting by taking part in bottom up initiatives in whole-catchment river restoration, hedgerow planting and woodland regeneration and the like. What I often find at the community level is a distinct apathy towards the issues, and from some, a determination to stick to ‘whit’s aye been’ and the acceptance that individual landowners have the right to do whatever they please on their land even when this is poisoning and silting up the river and creating increased flood risk downstream. Land management practices including the shooting and trapping of species regarded as pests (cormorants, goo sanders, seals, foxes, badgers etc) are still also condoned. For these reasons, I really dislike and rail against the incomer/native dichotomy characterisation in the comments above although I accept that this may well be based on personal experience. There is a failure too at local authority level to foreground nature recovery in planning legislation although there is some hope that the National Planning Framework 4 might go some way to address this and make Biodiversity Net Gain more important than it currently is. Going back to local agency, community councils can also be filled with climate deniers, individuals resistant to change or ignorant of the need to change or who simply don’t have the time in their busy lives to contribute. There is little culture of participative democracy and that is where the discussion of land reform is relevant in this context too. I’m just not sure how the models discussed above for the Highlands might apply in my lowland setting but I am perfectly sure that local agency is not going to sort the climate and biodiversity crises when the local populace doesn’t give two hoots about them.

@Michael Farrell, in my experience of political science and theory, few aspects of political systems are as grossly overrated as Will, and few aspects are as perversely undervalued as Health (in the widest sense). There can be a kind of fetishisation of Democracy as a result, even where it is obvious that Democracy is in terrible poor health and shows no sign at all of being able to heal itself. Democracy needs a framework in which to thrive and become sane, well-informed, supportive of non-human life.

Soil and Soul was part of my induction to Eigg and I have enjoyed it greatly – and have gone back to it more than once – not least for reading of the activities of folk before I came to know them!

Thoroughly in agreement on the point you make about local initiative Alastair.

I understand there are different priorities between community and climate. But I want to have my cake and eat it. It is frustrating when there seem to be, for want of some ambition and trust, methods available to achieve that.

Some very good comments above on local democracy, on having both the environmental and the social cake to eat, and on Lowland community dynamics often blighted by “the acceptance that individual landowners have the right to do whatever they please on their land even when this is poisoning and silting up the river and creating increased flood risk downstream.”

I always feel that when down in the Scottish Borders, where big landlordism feels much more and the acceptance that individual landowners have the right to do whatever they please on their land even when this is poisoning and silting up the river and creating increased flood risk downstream accepted than it is up north and west..

Recently in D&G I couldn’t help but notice so many whitened farm buildings, devoid of soul and mostly tenanted from the Duke of Wherever. It just felt so sad. So oppressive. Ghost-like. And I’m sorry those for whom this goes too far, but so damned colonised! I yearn for yet more of Scotland to wake up. To re-member, re-vision and re-claim: https://www.alastairmcintosh.com/articles/2008-Rekindling-Community-McIntosh.pdf

“The meek shall inherit the Earth, and the meek are getting ready.”

Spot on Alastair!

I have this feeling too when visiting some of Scotland’s heavily Lairded villages and glens. A kind of stagnant, dead creepiness. And a sadness too. Tinged with rebelliousness.

Felt it recently when stopping in Kenmore by Loch Tay. Dunno the current ownership, but the identikit buildings tell of human expression subsumed.

https://goo.gl/maps/wBiQXqnSyR5iRKLz5

A thought: Every time we post on this site, we have to tick a declaration that says “I am not a robot”. I hope we can live up to that.

This is an authoritative contribution to the debate.

The idea of any single entity acquiring up to 20 Highland estates terrifies me. The land will be locked up for ever and we will be locked out.

Land is wealth. Land is power. Land is everything. We can’t afford to lose it to “investors” (extractors).

“Roll up!, Roll up!, Scotland is for sale. Parcelled up, sanitised and commodified. Burn your oil with a clean conscience! The Scottish Straths will launder your dirty work and your public image.”

As one of the world’s most-nature depleted, financially wealthy and iniquitous countries, Scotland/UK will soon run aground on our own territory, linked to our global ‘shipmates’ by the failing atmosphere and the dying seas that our wealth creates.

We suspect that there are worrying social and political tipping points lying ahead. But it is NOT JUST A SUSPICION that without a massive land-sparing for nature recovery, climate breakdown will destroy life on Earth. Nature recovery at the scale and speed needed is a huge change that all rural landowners must deliver now, with the whole country’s support. And I do NOT believe that this particularly requires, nor hampers, the struggles to tackle, where needed, the disproportionate influence of personal land monopolies, to reverse environmental and social exploitation.

A big cultural plan for change is needed, to have any chance of addressing the current recipe for ecological and geopolitical disaster. It cannot wait for all the glitches to be micro-managed out for everybody. As a start, the Scottish Government had better quickly specify the % of Scotland that is required to be spared for nature by all landowners by 2030, across all of rural Scotland, not just the Highlands. Then we can watch how nature recovers.

Loved your essay above in illuminating crucial questions and thinking imaginatively of possibilities. Can you point me to any study showing how any percentage can be returned to non resident investors without causing some ecological / social damage. I know that’s a bit broad but given that many land use activities run at a net loss to Estates, where is surplus for investors coming from?

I can’t point to any study showing such returns on invesnment, Sarah. As I say in the essay, ““Unless it has, say, a windfarm or asset strips/speculates, I’ve yet to hear of a Highland estate that returns 5% + dividends.”

I think that Highlands Rewilding will be looking to trade carbon credits and if/when they come on stream, biodiversity credits. It’s been suggested to me that the latter is Jeremey Leggett’s main interest. I would imagine renewable energy will be part of the equation, and above all, massively escalating Scottish land values given that Scotland is seen as being a relatively save harbour internationally from political upheaval and climate change, plus the carbon incentives that are already affecting land use planning in ways that are usually outwith the control of local communities. Some links on carbon credits, esp as affects Scotland:

https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/83777/1/Hannon_etal_Can_nature_based_voluntary_carbon_offsetting_benefit_scottish_communities.pdf

https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/79657/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837722005518?via%3Dihub

https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/1/29/greening-ourselves-to-extinction

And thank you to Wul and D. Tollick for their points. I think the latter’s point shows how relentless this procees could be. It worries me, because if people are not carried along with the cultural aspects of major land use change, it turns people against environmental imperatives, and in democracies that becomes a self-defeating political problem. Short of saying “go nuclear” – but mindful of all the issues that would raise – I am sorry that my answers are not more adequate when it comes to making reductions in CO2 emissions. I’m also mindful that many countries don’t have the options Scotland has for renewables and nature carbon capture. Those are the issues that I wrestle with in my book, “Riders on the Storm: the Climate Crisis and the Survival of Being”. At the deepest levels, these are questions of our humanity, and what can’t give no satisfaction in a consumerist-driven world.

Many thanks Alistair and especially for the additional links. More food for thought … and depression! Must reread last chapters of your Riders…. book.

This has been totally captivating to read through both the article then the comments. I am another resident in the south of Scotland and I am very interested in watching how the Langholm moor purchase develops [so far quite impressive] Then today (the 5th) I was somewhat blindsided by this [huge] development, as soon as I read it I thought I’d share it with this group, I’ll attach a link but the organisation in question is called ‘Oxygen Conservation’, I’d be fascinated by your thoughts.

https://www.oxygenconservation.com/about-us/

Regarding Oxygen conservation – I note most of the portfolio is in England, a few in Wales and the Firth of Tay in Scotland. Looking at the Tay more closely, 212 ha on north side, I see they will be working with a number of conservation organisations… not sure where any other community is but may be irrelevant given the site. I’m sure the RSPB will have a view sometime. OC’s website is very swish and attractive, and all their objectives may sound right on – but basically green gaslighting / green washing by new investment companies is exploding cos there’s money in carbon offsets (also very contentious and becoming discredited in some instances). They really have to show not just pretty pictures and words but a serious analysis and possibly peer reviewed reports which include all the other partners on the social, economic and ecological impacts of the projects they seem to be supporting. So I am highly sceptical at the moment until there is some substantial evidence! Langholm was a true community buy out and they have got a lot of challenges ahead (I know the area well) but the community is in control.

Martin (and all), I can’t add much to what Sarah has seemingly very competently said. I do notice that the name “Oxygen Conservation” could give a misleading impression that it’s about stopping the Earth’s O2 from running low. That is not considered to be a likely scenario, and probably OC are merely intending it to signify that which is life-sustaining.

On the question of offset credits. Let’s remember that these allow bad things to be done in one location, paid for by doing good things in another location. In addition to the carbon offset credits mainly discussed here, bough by airlines, delivery companies, etc., the other up and coming thing is biodiversity credits. I am no expert in this, but in a UK context (or maybe just England & Wales) I picked up this explanation online:

“The credits can be bought by developers as a last resort when onsite and local offsite provision of habitat cannot deliver the Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) required. The price of biodiversity credits will be set higher than prices for equivalent biodiversity gain on the market. The intention is that this system will be run by a national body, not at the local level. We expect more information on the national biodiversity credits scheme to be included in the forthcoming Defra consultation on BNG secondary legislation.”

Source: https://www.local.gov.uk/pas/topics/environment/biodiversity-net-gain-local-authorities/biodiversity-net-gain-faqs

In a Scottish context, there is a briefing paper here:

https://cieem.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Implementing-BNG-in-Scotland-Apr2021-1.pdf

And it looks like there’s a £2/3 million contract pending or out from the Scottish Government to deliver a biodiversity credits system to “enable investment in Scotland’s nature.”

https://iuk.ktn-uk.org/opportunities/civtech-8-challenge-design-biodiversity-credits-and-enable-investment-in-scotlands-nature/

I will hold back from comment as I don’t know enough about this area to be confident of being on solid ground.

Would it be possible to create a community body that could buy a substantial block of the offered shares using a grant from the Land Fund, possibly supplemented by crowd funding? This would give the community an active role in the management of the Estate? Even a fifth of the shares (£2m) would give the community considerably voting power. If there isn’t enough time to consider this for Tayvallich would it be a way forward in any future proposals using the same model?

Yes, Sharon, and I believe that at least one of these communities is thinking along such lines with Highlands Rewilding. I think it could be a very fruitful part of seeking a win-win relatioinship that allows for both rewilding, and repeopling, with the local community afforded agency. If this is played wisely, Jeremy Leggett and his colleagues can help to pave a way that could gather support rather than suspicion on the ground. Nobody doubts that as we look into the future, new patterns and examples are needed, and my main motivation in writing this piece was to help stimulate thinking around such openings of the way.

Interesting article in FT 6 Feb 23 ‘The case for a land value tax is overwhelming’ by Martin Wolf. He emphasises the economic efficiency and moral justification for such a tax. He quotes from a paper from the Centre for Economic Policy Research in 2021 (see summary here https://cepr.org/publications/dp16652) in which modelling suggested a 5.55% land value tax, balanced with reductions in taxes on capital and labour derived income of 28 and 10 percentage points respectively would raise output by 15% over trend (based in the USA).

Wolf mentions that the reason LVT has not been introduced has been due to the political power of the land-owning classes. But surely that is not the case in present-day Scotland. Does this not represent an open goal for the SNP government? Can they be persuaded to look seriously at such radical policies instead of obsessing over matters which, however righteous they feel they are, will do nothing either to improve Scotland’s very poor economic performance or further the case for independence?

I agree, but if I can refer you back to my response of 1st Feb (above) you’ll see the political reasons why I think it’s “long time coming’”.

Folks, I reckon the responses to this essay will be pretty much fizzling out now. There’s a lot more on Twitter linked to @alastairmci and @bellacaledonia. The bottom line is how to restore both the natural ecology and the human ecology of belonging to the land. Keep up the work on both these fronts, in lockstep if you’re able to. And thanks to Mike Small and colleagues for holding space on this site.

Thank you Alastair for the original post and continuing to contribute below the line. There’s been some really interesting and provoking comments. Thank you to BC for hosting.

I appreciate people have different reasons for heading to Twitter to continue discussion (just as I still have to use it for work) but I hope we’ll meet instead at a place without such thoroughly objectionable owners!

(Mods – would you consider an ActivityPub plug-in for the site?)

Hi Ben – tell us about ActivityPub plug-in?

This is a WordPress site I think?

ActivityPub is here: https://wordpress.org/plugins/activitypub/

@Ben, the developers describe the plugin as being in Beta, so that along, apart from other considerations, should dissuade any administrator from installing it on a production website, unless as part of a testing programme. With such plug-ins, I would expect a privacy statement, none of which is given, which is another no-no. Here are the official developer guidelines:

https://developer.wordpress.org/plugins/privacy/

Thanks, I’ll take a look

For the record, I just want to add here a string of tweets about the timescales of carbon capture through the sale of carbon credits by one of the world’s leading climate change science commentators, Zeke Hausfather of Carbon Brief.

https://twitter.com/alastairmci/status/1634580813424541697?s=46&t=5ImNF19G60enAI7omsnB8Q

The tag #PFI in my introductory tweet there refers to the £2 billion ‘private finance intiative’-like deal that the Scottish Government have announced. See former SNP MP Roger Mullin’s thread, and especially, Andy Wightman’s article that he has quote-tweeted in it, here:

https://twitter.com/rogmull/status/1631980177755455490?s=46&t=5ImNF19G60enAI7omsnB8Q

Rewilding is not the way to go, per see. A much better approach is the BioRegional approach, incorporating rewilding as a subset within bioregions.

What is worrying about land at the moment are the machinations of the New York Stock Exchange:

1. Intrinsic Exchange Group

Intrinsic Exchange Group (IEG) is pioneering a new asset class based on nature and the benefits that nature provides (termed ecosystem services). These services include carbon capture, soil fertility and water purification, amongst others.

This new asset class is the foundation of a new form of corporation called a “Natural Asset Company” (NAC). The primary purpose of these companies is to maximize Ecological Performance, and the production of ecosystem services, which they have rights and authority to manage.

In partnership with the New York Stock Exchange, IEG is providing a world-class platform to list these companies for trading, enabling the conversion of natural assets into financial capital. The NAC’s equity captures the intrinsic and productive value of nature and provides a store of value based on the vital assets that underpin our entire economy and make life on Earth possible.

https://www.intrinsicexchange.com/

2. Introducing Natural Asset Companies (NACs)

To address the large and complex challenges of climate change and the transition to a more sustainable economy, NYSE and Intrinsic Exchange Group (IEG) are pioneering a new asset class based on nature and the benefits that nature provides (termed ecosystem services). NACs will capture nature’s intrinsic and productive value and provide a store of value based on the vital assets that underpin our entire economy and make life on Earth possible. Examples of natural assets that could benefit from the NAC structure include natural landscapes such as forests, wetlands and coral reefs, and working lands such as farms.

https://www.nyse.com/introducing-natural-asset-companies

Glasgow CC created a £30 billion stock portfolio in downtown Glasgow and presented it during COP 26:

“Glasgow launches £30bn ‘Greenprint for Investment’, a portfolio of transformative climate investment projects to boost 2030 Net-Zero goal

Glasgow City Council today (23 September) launched its ‘Greenprint for Investment’, a portfolio of investment projects designed to give a significant boost to the city’s target to reach Net-Zero by 2030. In June, the city announced that it had reduced its carbon emissions by 41% since 2006, surpassing the 30% target Glasgow set for 2020.”

https://www.glasgow.gov.uk/index.aspx?articleid=27563

However, they are not alone, the SLC has voiced similar policies on publicly held land. These approaches are nothing more than an attack on the commons by commodifying the commons.

Personally, I would take a much longer time thinking about how this is implemented as there are serious concerns about net zero and rewilding becoming another land grab.

Scotland is on the global frontlines of The Great Net-Zero Land Grab

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/scotland-is-on-the-global-frontlines-of-the- great-net-zero-land-grab/